Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

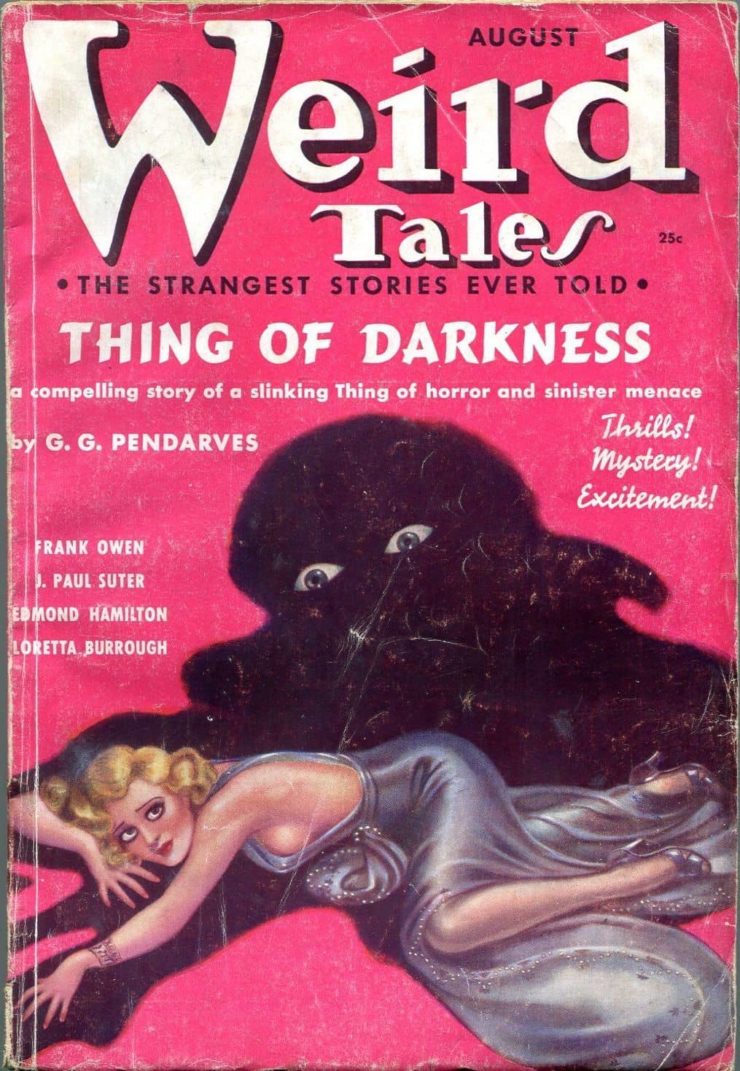

This week, we’re reading Manly Wade Wellman’s “The Terrible Parchment,” first published in the August 1937 issue of Weird Tales. (Note that there are several places where you can ostensibly read it online; all have serious errors in the text. We found it in The Second Cthulhu Mythos Megapack.) Spoilers ahead.

“After all, we’re not living in a weird tale, you know.”

Summary

Unnamed narrator’s wife Gwen has an odd encounter at the front door of their apartment building. A “funny old man” pops up with a stack of magazines, including Weird Tales. As narrator’s a fan, she buys it for him. It must be an advance copy, though, since it’s not yet the usual publication date.

A sheet of parchment falls from the magazine. Both reach for it, then recoil from the yellowed and limp page. It feels clammy, wet, dank. They examine the parchment and find that it retains the impression of scales, as if made from reptile skin. The faint scribbling on it looks to be in Arabic. Narrator suggests they get “Kline” to decipher it, but first Gwen points out the apparent title: a single word in ancient Greek, which she transliterates as “Necronomicon.”

Narrator infodumps that the Necronomicon is Lovecraft’s fictional grimoire, featured in many of his stories and in those of his circle. The supposed work of supposedly mad sorcerer Abdul Alhazred, it’s become a cult object among weird fiction fans, a modern legend. So what is the parchment, a sort of April Fool’s joke for WT readers?

But look: Now the last line of characters is written in fresh, dark ink, and the language is Latin! She translates: “Chant out the spell, and give me life again.” Too strange—they better just play some cribbage. (Not that real geeks ever react to terrifying events by retreating into board games.)

While they’re playing, the parchment falls from narrator’s desk; when he picks it up, it seems to wriggle in his fingers. The weight of an ashtray isn’t enough to confine it—it slides out from under, and now the last two lines are changed. Both are in English now; the penultimate one reads: “Many minds and many wishes give substance to the worship of Cthulhu.”

Gwen hypothesizes that this means so many people have thought about Lovecraft’s creations that they’ve actually given them substance! And the language on the parchment keeps changing to make it easier to read.

Much too weird—let’s go to bed. Narrator confines the parchment in his big dictionary until Kline can consult on the mystery.

Sleep long evades the couple. Narrator dozes off at last, but Gwen wakes him. He hears what she’s heard: a stealthy rustle. He turns on the light, and out in the parlor they see the parchment escaping from its dictionary-prison, limply flowing from between the leaves like “a trickle of fluid filth.” It drops to the floor with a “fleshy slap” and creeps towards the bedroom as if on legs—think a sheet of paper draped over a turtle’s back.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

While Gwen cowers, narrator steels himself to defend her. He gets up, sees the parchment hunch over the bedroom threshold like “a very flat and loathly worm.” He throws a water glass. The parchment dodges, then almost scampers toward narrator’s bare toes. He seizes the only available weapon, Gwen’s parasol, and pins it to the floor. Stooping, he sees that all the writing’s changed to freshly-inked English, and he reads the first line…

Many times since he’s yearned to speak that line, but he’s resisted the urge. The words form too dreadful, too inhuman, a thought! To say them aloud would initiate the end of man’s world! Narrator reads no more. The squirming parchment scrap must indeed be the result of Lovecraft’s fancy, created or invoked by his readers’ imaginations. Now it serves as “a slender but fearsome peg on which terror, creeping over the borderland from its own forbidding realm, [can] hang itself” and “grow tangible, solid, potent.”

Don’t read the writing, narrator raves at Gwen. Remember what she’s read already, about chanting the spell and giving something life.

The parchment frees itself and climbs narrator’s leg. It must mean to drape itself over his face and force its “unspeakable message” into his mind, compelling him to summon Cthulhu and his fellow horrors.

He dashes the parchment into a metal wastebasket and seizes his cigarette lighter. The other papers in the basket ignite under its flame; from the midst of the conflagration comes the “throbbing squeak” of the parchment, “like the voice of a bat far away.” The thing thrashes in agony but doesn’t burn. Narrator despairs.

But Gwen scrambles to the phone and calls the neighborhood priest. Father O’Neal hurries over with holy water—at its “first spatter, the unhallowed page and its prodigious gospel of wickedness vanished into a fluff of ashes.”

Narrator gives thanks every day for the defeat of the parchment. Yet his mind’s troubled by a question Gwen asked: “What if the holy water had not worked?”

What’s Cyclopean: The parchment is dank.

The Degenerate Dutch: Narrator’s wife takes on the role of damsel-in-distress, hiding behind the pajamaed hero, from any pulp cover. (To the modern reader, the fact that she needs to gamble playfully with her husband for spending money may be nearly as creepy as the titular parchment.)

Mythos Making: Make too much Mythos, this story suggests, and something may hitch a parasitic ride on that new-formed legend. Wellman calls out Lovecraft and Smith and Bloch as creators of the hazardous tales. (Translator Kline, however, is no relation to weird fiction author T.E.D. Klein, born a decade later.)

Libronomicon: Watch out for off-schedule issues of Weird Tales. And self-translating advertising inserts with excerpts from the Necronomicon.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Insomnia seems like an entirely fair reaction to sharing an apartment with an animate summoning spell.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Well, that was a roller-coaster. We start with what looks like a fun story in the spirit of “The Space-Eaters,” but more lighthearted and humorous—the sort of thing likely to end in the affectionate fictional murder of at least one Weird Tales author, with fond-yet-sharp portrayals along the way, maybe a nice game of Spot the Reference. And then the parchment-thing starts crawling up his leg for a forced read-aloud—ahhhh, no! Actually creepy! And then, much like Space-Eaters, things take a sudden left turn into the Proto-Derlethian heresy. Ahhhh, no! But at least this time there’s no sentimental blather about why the holy water works—it just… works.

I would have sorta liked to see the scene where they explain the demonic possession of their wastebasket to the local priest, though. Then again, given his emergency-response speed, maybe he’s used to it.

Either that or it’s his fifth call of the night. A much better question than What if the holy water hadn’t worked?—who cares? It did!—is Hey, what happened to the rest of the ‘armful’ of magazines the ‘funny old man’ was carrying? Did he distribute face-eating Necronomicon pages to the whole block, or is this a “choose and perish” situation? If you’re expecting a copy of Family Circle, will you end up with one of the terrifying children from our last few posts, or will you still get the instructions for Dial-a-Cthulhu?

But I’ll forgive a lot for the amusing opening and genuinely disturbing middle bit, and a nightmarish image that I had not previously considered. I will now not wander around my messy room before bed, double-checking the texture of every character sheet that I’ve failed to put away. I’m sure they’re all fine.

What’s particularly nice is that the animation of the page is in service of, rather than replacing, the things that are already scary about a summoning spell. We’re all compulsive readers, right? So a thing that, if you read it, leads to deadly peril, is a natural (or unnatural) nemesis. This one even pays attention, and makes itself more readable over time, like Google Translate for unholy rites. Then there’s that first line—like so many secrets man was not meant to know, something that can’t be unseen. Something that urges itself to be read aloud, or written, to release the pressure of being the only one who knows—but again, if you do, deadly peril.

Some people can’t resist. The King in Yellow particularly lends itself to sharing, while some people do better than others with the Lost Tablets of the Gods. Lovecraft’s protagonists inevitably write things down, to be read by second- and third-hand reporters and then shared with dire warnings in the pages of, yep, Weird Tales.

“Lovecraft Was Right” stories vary in their success—I like this one because it suggests less that HPL had some sort of line on horrifying cosmic truth, and more that the creation of a mythos always makes cracks for Something to get in. It could happen every time a legend takes off, and the Things coming through merely parasitize the newly-created stories. Was Cthulhu—by that name, tentacles and all—waiting for someone to introduce Him to humanity for 25 cents? Maybe not. Was some entity, for the sake of being Called, willing to answer Cthulhu’s recently-assigned number? Absolutely.

Many minds, and many wishes, give substance. So be careful what you wish—and worse, be careful what you read.

Anne’s Commentary

My sense of humor must have been in PAUSE mode when I first read “The Terrible Parchment.” Either that or Wellman keeps so straight a face throughout that he tricked me into taking his story seriously. It was probably some of each, my momentary tone-deafness and Wellman’s tone-deftness. We wanted to jump back into the deep end of the Mythos pool this week, and hell if we didn’t. “Parchment” swarms as thick with Mythosian tropes as a dry-season Amazonian pond with piranhas—piranhas whose starved hunger is so exaggerated that it’s funny as well as terrifying. Funny, that is, unless you’re the poor slob who’s fallen into the pond, and which of us would be so incautious as to buy a copy of Weird Tales from some sketchy street vendor?

Nope, Bob Chambers has taught us the dangers of reading just any literature that happens to drop into our laps. And M. R. James has warned us never to accept items “helpfully” returned by strangers, at least not without immediately inspecting them for scraps of cryptically inscribed paper. Or parchment, which is worse, being made from the skins of animals rather than relatively innocuous plant fiber. Parchment generally comes from goats, sheep and cows (or their young, in which case it’s called vellum, a fancier word-substrate.) Wellman ups the creep-factor of his parchment by giving it scale-patterning, hence a reptilian derivation. I like to think his parchment’s made from the skin of anthropomorphic serpents, like Robert E. Howard’s Valusians or the denizens of Lovecraft’s Nameless City. That would double the creep-factor by bringing in the trope-ic notion of humanodermic writing material.

I think I made “humanodermic” up—at least Google doesn’t recognize it. So much the better, because May is Neologism Month, right?

Wellman, who wrote in many of the “pulp” or popular genres, is best known for his “John the Balladeer” tales, which feature an Appalachian minstrel and woodsman who fights supernatural crime with his silver-stringed guitar. Is “Parchment” his only contribution to the Mythos? I can’t think of another—please relieve my ignorance if you can, guys!

In any case, “Parchment” packs in enough tropes to satisfy any Golden Age pulpeteer’s mandatory Mythosian requirement. Because Wellman delivers the story with forked-tongue-in-cheek gravitas, I was initially annoyed by the overabundance of Lovecraftisms. We start off with the standard unnamed narrator who’s suddenly confronted by cosmic horrors. The joke is that they come to him via his devotion to the iconic Weird Tales, a pulp to which Wellman frequently contributed. The “vector” is the standard nefarious stranger, here a “funny old man” distributing untimely mags with extras. It appears this guy doesn’t brandish his wares at random—he’s after readers already immersed in, well, weird tales, and he knows who they are, and whom they’re married to, and where they live. His targets are exactly those readers and writers who’ve brought Cthulhu and Company and All Their Accessories to life by an obsession with Lovecraft’s fictional universe, in which they’ve become co-creators, potential co-keys to a dimension of beings inimical to man.

Wife Gwen plays several trope-ic roles. She’s the associate of the narrator who gets him involved in a Mythosian crisis—the vector’s vector. She also takes on the scholar-professor role, conveniently filling in gaps in the narrator’s knowledge. She translates Greek and Latin; she’s conversant in standard mythologies, like that of the chthonic gods; she takes the lead in speculation—it’s Gwen who suggests that the joint-confabulation of Lovecraft’s circle and readers has given form to the parchment and to preexistent alien entities. Later she lapses into the role of helpless fainting female but quickly recovers when protector-male narrator fails to protect adequately—it’s Gwen who calls in priestly assistance, and who knows to tell Father O’Neal to bring holy water. [RE: I’m guessing folklore studies professor?]

Help me again, guys. Is August Derleth’s “Return of Hastur” (WT, 1939) the first substantial manifestation of his “evil Elder Gods vs. good Elder Gods” heresy? If so, Wellman’s “Parchment” (WT, 1937) anticipates that approach to defeating Lovecraft’s monsters, only with a full-on Christian remedy: Holy water as Elder Sign. Or maybe Wellman is nodding to Long’s “Space-Eaters” (1928), in which the Sign of the Cross defeats eldritch horrors?

Side note: I don’t know about whether religious paraphernalia can ever daunt Cthulhu and Company, but I’m pretty sure that cribbage won’t. Really, guys? You come across an impossibly mobile and mutable ancient parchment, and your response is to shrug and play cards?

Anyhow, Gwen’s holy water works. Or does it? Since the “funny old man” had a bunch of magazines under his arm, narrator wasn’t the only WT reader he meant to gift with a loyalty bonus. Even less should we suppose that all such bonus recipients would have wives as capable as Gwen or neighborhood priests as willing to trot over with holy water in the middle of the night for ill-defined mystic emergencies.

Oh, last tasty trope, the parchment itself, a living text. Grimoires like the Necronomicon are often described as feeling too warm or skin-textured or otherwise animate to be inanimate objects. Wellman outdoes the competition with some unforgettable images, both horrific and absurd, the best being how the parchment plods along like a turtle draped in brown paper. It can also slither like a snake and scamper like a lizard, all the cool reptilian things.

Its full-grown descendant must be Hagrid’s Monster Book of Monsters. I’d like to see holy water put that tome down.

Next week, we’ll meet a different—maybe more traditional—sort of predator in Amanda Downum’s “The Tenderness of Jackals.” You can find it in Lovecraft Unbound.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I think the “Kline” referred to in the story was Otis Adelbert Kline, longtime pulp writer and agent for pulp writers, best known for writing pastiche/homages to Edgar Rice Burroughs. He was also an amateur “orientalist” and a student of Arabic, so it would make sense they’d see “Kline” about a translation.

@@@@@ Anne- I think the generally accepted term (for a given value of “accepted,” especially “as small talk at the dinner table,”) for “Made of human skin,” is “Anthropodermic,” or, if referring to book-binding specifically, “Anthropodermic bibliopegy.”

With regards to Gwen, she seems to have good instincts in calling for the priest, but our rereaders’ description of her as “damsel-in-distress, hiding behind the pajamaed hero, from any pulp cover,” makes me long a bit for Miss Colby, from Wellman’s “The Golgotha Dancers,” who answering a cry of distress from the narrator to find him besieged by animate figures emerged from the eponymous painting, seizes a paper-cutter from his desk and wades in.

According to the editor’s blurb in Weird Tales, Wellman said this was “a Necronomicon story to end all Necronomicon stories.”

Our narrator here is not unnamed. His name is Manly Wade Wellman. Kline is indeed, as Russell H suggests @1, Otis Adelbert Kline. Both men lived in Chapel Hill, NC (as did E. Hoffman Price and, much later, David Drake; there’s a whole little genre-writers’ enclave there, much like the one in New Mexico). Kline had been a fairly popular pulp writer whose name would be known to readers, though he had shifted to being a literary agent by the time this story ran (notably representing Robert E. Howard and later REH’s estate).

All the name dropping going on in this story is the sort of thing readers ate up with a spoon back when letter columns made up communities not unlike various comment sections on the Internet do today. It was all a nod and a wink to dedicated readers.

May is Neologism Month!! <3

The interesting thing about the ending is that it specifically calls out the narrator (and presumably Gwen as well) dwelling on a question. In a setting where thinking about things a lot can make them real, does this mean that the next Terrible Parchment to turn up somewhere won’t be vulnerable to holy water?

When I saw the title, I imagined the Elder Gods playing cribbage. Of course, they would be cheating.

A primary lesson of this story is one should never buy magazines from door-to-door vendors.

I love Wellman’s work. I’m sure he has more Lovecraftiian work, but my Carcosa Press collection is stored away.

This story reminded me of Harlan Ellison and the cigarette ads- not so immediately lethal, but…..

If I were to be gifted a self translating parchment to summon Great Cthulhu, do you think I would wait a nanosecond? Hell, no! I would summon him without a second right, you can be sure. And even without the parchment I can tell you what the chant is:

Ph’nglui mgwl’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn. Iä iä Cthulhu fhtagn!

We all know it.

Start chanting now.

By the way, it was a terrible story. I couldn’t find anything funny in it.

Russell H @@@@@ 1: Nice catch!

DemetriosX @@@@@ 3: That’s what I thought at first, too. But the narrator isn’t Wellman unless he’s replaced one and only one real person: Manly’s wife was Frances Garfield, another Weird Tales author. Not someone who’d suggest that the new issue was only a treat for her husband, or who’d be unfamiliar with Lovecraft’s creations.

SwampYankee @@@@@ 6: If you get a customer to summon Cthulhu, you get the really good prize for the Magazine Drive. (Does anyone else remember those?)

Now that I think about it, the scaly leather is probably sapiodermic. Both anthropo and humano may make unwarranted assumptions.

The Tenderness Of Jackals – I just found and read it online, so you can too, and I’m not going to provide a link – is brilliant. It’s also actually Lovecraftian, unlike a lot of the recent reread material, and I would love to see what the Reread has to say about it.

@9 Ruthanna: Good point. I hadn’t thought about just who Wellman was married to and just assumed. Both parents Weird Tales authors. Makes you wonder why their son Wade went into psychology.

@@@@@2. CuttlefishBenjamin: I am rather more than a little alarmed by the fact there’s an actual, official category for books wrapped in HUMAN SKIN (it’s almost as frightening as contemplating the psychology underpinning a language with a word for ‘Kill every tenth man’ …).

@@@@@8. Biswapriya Purkayastha: Such an interesting attitude to the subject of Cosmic Horror – please excuse me, I have a few friends to contact 39,000 years from now and I’m sure they’ll be absolutely DELIGHTED to hear your explanation for such an enthusiastic dive into Maleficarum …

“EVERYBODY EXPECTS THE IMPERIAL INQUISITION!”

Goodness me,that was quick – Inquisitor Python (Ordo Xenos) is quick off the mark this time …

@2 ED: It may comfort you to hear that out of thirty-one allegedly human leatherbound books examined by the Anthropodermic Book Project, thirteen proved to be sourced from other animals. Of course, after some quick arithmetic, you may have quite the opposite reaction.

My favorite example is “Narrative of the Life of James Allen,” the death-bed memoirs of a highwayman dying in prison which was, per his instructions, bound in his own skin and delivered to one guy who had shot back when Allen tried to rob him. Presumably he was remarkably convincing in his assurances that he was not a wizard, and this was not an elaborate revenge curse.

On vaguely related use of human skin, I remember an article (not a story) mentioning a European military leader (king, duke, something like that) who ordered that his body be flayed and his skin tanned to use as a drumhead so he could continue to lead his men into battle.

Looking at the Wikipedia article on anthropodermic bibliopegy, I see that four of the confirmed cases of books bound in human skin are at Brown University in HPL’s (and Anne’s) beloved Providence. They’re only in second place (by one), though, behind the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where the books are on display in the Mütter Museum.

@14 swampyankee: That rings a bell. I thought it might have been Nelson, but apparently not.

@15,

After a bit of googling, it was Jan Žižka

Man, I’ve been waiting to see you guys do Wellman, he’s my second favorite Weird Tales author after Lovecraft. He’s also got a few very short stories that are directly mythos attached (A book seller offers the Judge a Necronomican, and laughs when he refuses) and one that’s John the Balladeer which runs with the same theme, One Other, found in Who Fears the Devil as likely the easiest to find.

Also, the Shonokin are great bad guys.

I was in a store several years ago getting a gift bag for a book. It was a cheery, well-lit, modern looking place, not at all the kind of place where you expect the teenage sales clerk to start talking about how she had always wanted to get a book bound with human skin (the book I was getting the gift bag for looked vaguely antique with guilt edging but wasn’t sinister looking). She had researched the matter thoroughly. Really thoroughly.

Then, a guy she knew came over and joined in the conversation. It seemed he knew about human skin book bindings and thought they were cool, too.

I’d seen enough horror movies to know what scenes like this seem to lead up to. I quietly made my way to the exit and fled into the night.

When I got home, I did research verifying that, yes, there are a few books out there. I didn’t find any pictures (and don’t want to see any, thanks), but I have this mental picature of a pale colored bookd with lines that, if you look closely, show a face screaming.

The store’s not there anymore. There one day and gone the next. They say it was the economy.

My super-duper theory that I came up with at work right now- without reading the story yet, mind- is that the holy water works not because of any innate power or because the Catholic Christian god is the true one, but rather the same forces that brought a page of the Necronomicon into being are the same forces empowering the exorcism. If a bunch of fans can bring Lovecraft’s pantheon to life, what about a church with millions of adherents?

I do believe this was Wellman’s only explicitly Lovecraftian work. I have a paper on Lovecraft and Wellman if anyone is working on this topic. I’m happy to send it to anyone interested. – wyattd@Lindsey.edu

@13 and 14, this kind of talk reminds me of two things, one being a story about an Old West robber who died (hanged or shot during a robbery, can’t remember which) and whose tanned skin was used to make a pair of shoes. These shoes do in fact exist and are on display in a museum somewhere in Wyoming (I think).

The other thing it brings to mind is, unfortunately, stories from Nazi Germany about the wife of the Buchenwald camp commandant who used the skin of deceased prisoners to make lamp shades. As far as I know, those stories have never been verified beyond a doubt–which is to say, nobody has ever actually found any of these human lamp shades; at least one lamp shade from the period that was suspected of being human skin was actually made of goat skin.