Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

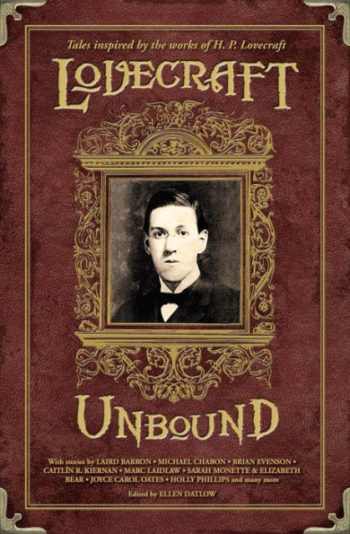

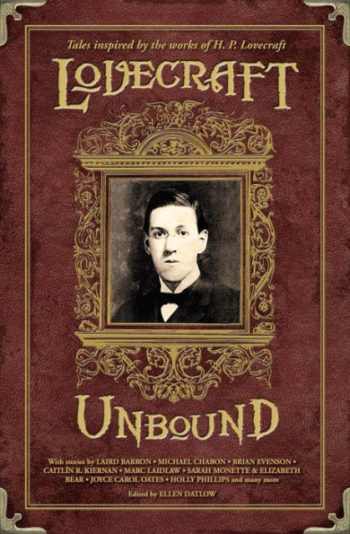

This week, we’re reading Amanda Downum’s “The Tenderness of Jackals,” first published in Ellen Datlow’s Lovecraft Unbound anthology in 2009. Spoilers ahead.

The train chases the setting sun, but can’t catch it.

Summary

Gabriel watches an express train pull into Hannover Station “as purple dusk gives way to charcoal.” In the whine of the train’s wheels, he hears the wolves.

Soon, the wolves whisper, and Gabriel’s cigarette smoke twists into the shape of a “sharp-jawed head.” A breeze disperses the phantom. Gabriel savors the upper-world air, which “doesn’t reek of the tunnels—musk and meat and thickening tension, the ghouls snapping as often as they spoke and the changelings cowering out of their way.” Ghouls and changelings alike knew the wolves were waiting, but no one wanted to answer their call. At last newcomer Gabriel emerged to placate the wolves.

The bright-lit station teems with students, commuters, tourists, officers, none suitable prey. Gabriel’s tension eases—maybe he won’t have to feed the wolves after all. Then he sees the boy in threadbare jeans, backpack hanging off one thin shoulder. A fall of dark hair can’t hide the sleepless shadows under his eyes. Too far away to smell it, Gabriel imagines the scent of the boy’s nervous sweat, and the ghost-wolves imagine it too. A soldier brushes past the boy, and for Gabriel the station shifts to a darker place, the soldier’s neat modern uniform to one stained and long-outdated. The station’s a between-place, where it’s easy for the “walls” to slip. The station shifts back. The boy exits. Gabriel follows.

The “strays” have always been wolf-prey. It started after WWI, in a Germany defeated and starving. Twenty-four men and boys were lured from the station, promised work or shelter or food or just a kind word. Gabriel understands their desperation—hadn’t desperation first led him to the ghouls? Twenty-four people murdered. Nothing compared to the genocide his Armenian grandparents escaped, or the holocaust of WWII, or the Lebanese civil war Gabriel himself survived. But twenty-four murders sufficed to birth the wolves.

Gabriel finds the boy crumpling an empty cigarette pack. He offers his own; the boy tenses but accepts. His accent is American. His hazel eyes are flecked with gold. The wolves approve.

Gabriel asks the boy’s name—thinking of him as Alec is better than boy or prey. The wolves lurk, unseen by passersby. They don’t care how Gabriel maneuvers to hook Alec; only the “red and messy end” of the hunt interests them.

Their first stop is a kebab stand. Gabriel signals the changeling vendor that Alec isn’t one of them, and so Selim serves the boy “safe meat.” Selim sees the wolves, and glowers unhappily. He doesn’t approve. Well, neither does Gabriel, but the wolves’ hunger has become his.

They leave the crowds behind, pause on a bridge over black water. Good place to dump a body, Alec jokes. Gabriel tells him about Fritz Haarmann, who sold the meat of his twenty-four victims on the black market. Alec reacts with disgust and fascination. It’s a complex emotion Gabriel remembers from bombed-out Beirut, when he first realized the shadows prowling the ruins weren’t soldiers or thieves or even human. It was easy to admire their strength when he was weak, easy to join them when he was alone and starving. As he is now.

Alec begins perceiving Gabriel’s “night-shining eyes, the length of his teeth and thickness of his nails.” He’ll run now, Gabriel thinks, and Gabriel will give chase with the wolves. Instead Alec asks, “What are you?”

A monster, Gabriel replies. A ghul—an eater of the dead, a killer too.

Alec’s palpably afraid, but touches Gabriel’s face with wonder. Gabriel feels he’s looking into the past, into a mirror. Confused, the wolves whine. A woman walking a dog passes below the bridge. He urges Alec to follow her. Instead Alec shows him burn scars and bruises—does Gabriel think kids like him don’t know about monsters, don’t realize there’s no safe place?

Gabriel says he doesn’t want to hurt Alec—they do. And Alec sees the ghost-wolves. Gabriel explains that the wolves are “the ghosts of acts, of madness and hunger and murder.” And they hunger for more. The Hannover ghouls got caught up in their curse when they ate the meat Haarmann sold, knowing its source. Ghoulish law is to eat only gravemeat. Gabriel’s broken it once, killing a soldier in desperation. That’s how the wolves caught him.

And me, Alec says. He’s tired of running. He’d prefer death at Gabriel’s hands. He pulls a butterfly knife and cuts his arm, flings blood-drops towards the seething wolves; further inciting attack, he bolts into a nearby park. Gabriel pursues. The wolves urge him on. He bites, draws blood—is Alec’s grip on his hair self-defense or encouragement? Either way, the boy is sobbing.

With dizzying effort Gabriel draws back. Alec curls up, choking that of all the monsters to meet, he has to meet one not monster enough. Gabriel says he’s a jackal, not a wolf. Ghouls haunt graveyards, eat corpses, skulk in the between-places. They steal children and change them. No, he won’t kill Alec, but he can steal him. It’s all he can offer. Alec looks at him with terrible hope, fear and longing. Then, again feigning unconcern, he asks, “Why didn’t you say so?” The wolves snarl that others will kill for them, Gabriel can’t stop it, can’t atone so easily.

“But I won’t be your killer,” Gabriel whispers, and Alec won’t be their prey. They’ll leave behind the haunted warrens of Hannover, settle elsewhere. It’s not enough, but it’s something.

It’s a life.

What’s Cyclopean: The border between organic and inanimate blurs. The train is sinuous, disgorging passengers; the station has glass and metal guts under stone skin; dusk has bruises.

The Degenerate Dutch: For Gabriel, the ghouls are an imperfect refuge from human-on-human horror: the Armenian genocide that his grandparents escaped, the Holocaust, his own civil war.

Mythos Making: What are all those ghouls doing, when they aren’t lurking beneath the cemeteries of New England?

Libronomicon: No books this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The wolves are ghosts of madness and hunger and murder.

Buy the Book

Lovecraft Unbound

Anne’s Commentary

Among the well-known carrion-feeders, jackals may be the most physically appealing—compare them to vultures and hyenas and maggots. To us herpetophiles, Komodo dragons are also pretty, but I guess most people would rather cuddle a jackal than the largest of the monitor lizards. Like Komodos, jackals are keen hunters as well as scavengers. That would make both species at least occasional “killers,” as Gabriel admits to being. The difference is that jackals and Komodos aren’t bound by clan law and custom to eat only carrion; they can eat whatever the hell they want and can get hold of. Jackals will eat plants at need. Komodos, most ghoul-like, have been known to dig up human graves and feast on the ripening contents. But jackals win the “tenderness” contest, monogamous pairs being the core of their social structure, which may extend to family groups of grown offspring hanging around to help rear sibling pups until they establish territories of their own. Folklore often represents the jackal as a cunning trickster. The Egyptian god of the afterlife is jackal-headed Anubis.

Anubis is also the patron of lost and helpless souls, a tenderhearted aspect Gabriel shares.

All of which is a roundabout way of admiring the aptness of Downum’s title, which may come across at first as an oxymoron. Jackals, tender? Those mangey followers of more capable predators, like the cowardly Tabaqui to Kipling’s Shere Khan? Those opportunistic sniffers after the dead and dying? Wouldn’t the more straightforward “Tenderness of Ghouls” be as oxymoronic-ironic? Probably, but since the forces antagonistic to Gabriel are represented as wolves, it’s defter to compare him to another canid.

In reality, wolves are as tender as jackals and have more “fans” among animal lovers and advocates. In Western tradition, however, wolves are—wolvish. They’re ferocious and greedy, bloodthirsty and rampaging. They’re big and bad and will blow down your house and eat your grandmother. They’ll chase your sleigh across the frozen tundra or ring your campfire or chill your blood to sludge with their (ever nearer) howling. They’re Dracula’s “children of the night.” Enough said.

Speaking of canids, Lovecraft’s favorite description of ghouls (after or tied with “rubbery”) is that they’re doglike. That’s no commendation from a passionate cat-lover. Underground dogs—dog-mole-human hybrids! Swarming through fetid burrows, gobbling up the anointed remains of 19th-century American poets, and worse of all corrupting the young of pureblood humans! Those are the ghouls Pickman painted, anyhow, who unlike Downum’s ghouls have no qualms about eating freshly killed people—didn’t Pickman represent them leaping through windows to worry the throats of sleepers or lurking in cellars or even attacking subway passengers en masse? Pickman would know, being a changeling himself.

Lovecraft’s Dreamlands ghouls are less horrific than their Bostonian cousins—in fact, they’re the friendliest creatures in the Underworld. Still rubbery and mouldy, still smelly, still doglike, still given to an unmentionable diet, but good allies in a pinch, even sympathetic for those who, like Randolph Carter, have taken time to get to know them and learn their meeping language.

Other writers’ ghouls tend toward one of these Lovecraftian camps. Downum’s ghouls fall between the monstrous and the other-but-relatable. Sure they’re monsters, as Gabriel admits, but there are much worse monsters, many of them human. Think of the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust. Think of people twisted by wars like the 1975 civil conflict in Lebanon. Think of the psychopath in 1918 Hannover who murdered twenty-four and sold their flesh in the black market. Ghouls at least try to avoid killing and have made the prohibition a central precept of their kind. If they sometimes fail, like Gabriel, it’s because they’re only human, sort of.

Humans, in this story at least, are the wolf-makers. What lowers the humans below the ghouls, ethically speaking, is that they’re not even aware of the wolves. Attuned to the between-places, ghouls perceive essential evil and know it for what it is. Sometimes they can even resist it, as Gabriel does. Members of an outcast race, they survive in shadow, but they do survive. What’s more, they take in other outcasts. Once upon a time it was Gabriel whom they “stole”—it seems “adopted” might be a better word in his case.

Adopted is a better word in Alec’s case as well—or whatever still-uncoined word could express the idea of being voluntarily stolen away from a “normal” but intolerable situation into an abnormal existence that’s far from perfect but still preferable.

Why is becoming a ghoul-changeling preferable? Gabriel tells us: because it’s a life, as opposed to Alec’s living death.

And, from the rubbery lips of a ghoul, what an indictment of humanity that is.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

He’s got me, Gabriel does. I do think monsters are interesting. Ghosts and ghouls, Deep Ones and Outer Ones, fungous vampires and laughing elder gods and mind-control spores and mind-destroying books. I’m interested in story-shaped monsters: the ones who do horrible things for all-too-comprehensible reasons, or for incomprehensibly alien ones, or because it’s their nature and a thing’s gotta eat (or reproduce, or shape reality in its immediate vicinity, etc. etc. through a universe of potential biological imperatives).

Realistic human monsters are another matter. The fascinations of the true crime drama, the detailed psychology of serial killers and order-following soldiers and order-giving dictators—I mostly find those interesting the way I might be interested in a blight on a vital crop, or a Category 5 hurricane bearing down on my city. But other people read them and watch them in endless profusion—again, Gabriel’s got our number.

And here’s a new type of monster, crossing the boundary: the ghosts not of people but of genocide and murder and pain-driven desperation, reaching out to cause more of it. Interesting, for sure, in all senses of the word.

Ah, but what does monstrousness look like to the monsters? Gabriel’s found refuge from the human monsters among the inhuman, or semi-human: the ghouls that congregate to gnaw on humanity’s dead. But they have a law: no fresh meat. And they’re human enough to have broken it. They may blame the wolf-ghosts, which are certainly there to help things along, but the timeline suggests another motivation. The murders—the original ones, the human killer who sold fresh meat to grave-jackals—got started after World War I, before World War II. That is, right after a period when ghoul-food was plentiful—trenches and fields full of it all across Europe—enough to support the recruitment of any number of changelings, the birth of any number of corpse-born ghoul babies. And then suddenly that flood drops to a trickle, down to the meager meals of ordinary graveyards. The ghouls were hungry.

Much like Gabriel. Much like Alec.

Layers of desperation. Layers of monstrousness. And the titular tenderness of jackals… which is what? Maybe it’s being the kind of monster that scavenges rather than kills—living mementos mori rather than murderers. Maybe it’s being the kind of monster that recruits, that takes in. Lovecraft was terrified of that possibility, and his stories are full of hospitable monsters that welcome outsiders into their communities. The K’n-yan may be fickle hosts, but will at least find you an affection group for a few months. Deep Ones seduce humans and offer a place in their cities to the most prodigal of their children. Mi-Go hold cosmopolitan salons between dimensions. Ghouls are the kindest of all, taking in changelings and wayward goths, and sometimes even wayward dream-questers.

Much like Kipling’s hyenas, ghouls accept a diet we may find horrifying, but it can’t be defilement when they’re simply following their natures. There may even be a weird sacredness to it. Especially if, as here, they’re just human enough that they could choose worse.

And choosing to do better… there are worse, and far more monstrous, ways to make a life.

Next week, a different take on both trains and ghouls in Robert Barbour Johnson’s “Far Below.” You can find it in The Weird.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

It took me a long time to get into this one. Right from the beginning, the combination of the name Gabriel and the wolfish imagery put me in mind of both Saki’s “Gabriel-Ernest” and the Gabriel Ratchet. Then came the geography. The Hanover Hauptbahnhof is enormous and, like all German train stations, non-smoking except in specified areas, mostly carefully delineated spots on the platforms. The station is also on the same side of the river as the Leineschloss, but the characters crossed the river before coming to the palace. Lastly, Hanover has no narrow, cobbled streets. The city was heavily bombed during the war and probably has fewer pre-War structures than any other major German city.

Once I got past all that — and I acknowledge that most of that is rather specific to me as a reader — I really enjoyed the story. Gabriel is Armenian, and I wonder when it was that he ate the forbidden fresh meat. He thinks of a soldier when recalling the incident. But was it during the Armenian genocide or perhaps later during the chaos and conflict with Azerbaijan following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Thinking about it, there is one other thing that bothered me about the story. I’m speaking here as a cis-het man, and the equation of homosexuals and predators was off-putting. It likely wasn’t Downum’s intent, but it’s a rather frequent and unfortunate trope.

@Demetrios

Since I’ve never been to Germany and don’t personally know Hanover, I didn’t notice the lacunae you indicated. However, I totally understand why they would grate on you. When I read stories by Western authors set in India, from HRF Keating to Elizabeth Bear, I’m so distracted by all the inaccuracies and implausibilities that I can barely notice the actual story. One of Bear’s stories, for instance, is set in Bangalore and features, among others, a Marathi police constable named Indrapramit (Bear obviously named him after he fellow SF author Indrapramit Das). Problem: Indrapramit is an exclusively Bengali first name, and a rare one at that; no Marathi was ever called by it. One of Keating’s tales has an “old green Mercedes” driving around Mumbai and the protagonist, Inspector Ghote, acting as though it was inconspicuous. Even today a Mercedes would be a rare sight in Mumbai, let alone forty or fifty years ago. Archer in one of his stories features an “Anil Khan”, which would be as likely a name as “Muhammad Jones”. Frederick Forsythe’s “There Are No Snakes In Ireland” has a Gujarati snake-seller called Chatterjee who refers to “Rajputana”. Chatterjee is a Bengali surname and nobody has used the term “Rajputana” in 70 years. The same tale claims that Indians have a tradition that the eldest son must be with his father when he (the father) dies. This must be an alternate dimension India where such a tradition exists, because I have never heard of it.

And so on.

That said, I enjoyed Downum’s story immensely. It was also refreshingly actually Lovecraftian, instead of most recent posts on the reread, where one has to, basically, take our hostesses’ word for it, and even then stretch one’s imagination to and beyond breaking point to find even a molecule of Lovecraft in them.

Now to see if I can find the text (I found exhaustive reviews) of Johnson’s Far Below online.

Whoa, I didn’t know Rudyard Kipling sorta-praised hyenas once. From my childhood love of hyenas: good on him!!

Edit to my comment no. 2:

Found Far Below online and read it. It’s…… interesting, in the way all stories that reveal that humans are the real monsters are interesting. Moby Dick comes to mind.

@3. AeronaGreenjoy

I think Kipling was talking about the Asian striped hyena, not the spotted hyena of Africa. At least I hope he was, because imputing that the spotted hyena is a pure scavenger is an insult to the most efficient predator on the African plains.

That makes sense. But hyenas of any kind seldom get praised, so I still count it as a win.

A general request: Anne and I both love doing the Reread, but we also fit this in around dayjobs, family obligations, and writing stories of our own. Please respect that this is less a systematic mapmaking expedition and more of a badly-calibrated teleporter. Sometimes one of us recommends a story we’ve read before; more often we pick them out based on recommendations elsewhere, brief blurbs, or intriguing first sentences. We do not have time to read them in full before I write the “next week” section of the post. Sometimes we find amazing stuff this way, and sometimes we find things that are a little iffy, and sometimes we make discoveries that allow others to avoid our mistakes. We also have an intentionally broad window on the weird, ranging from explicit Mythos stuff to the outskirts of the subgenre, where the boundary is fuzzy enough that it’s easy to stray over the edge. We always try to be entertaining, and to find some angle on the rest of what we’ve read–but we feel lucky to have a teleporter at all, and don’t intend to fiddle with the settings lest we break it.

DemetriosX @1 and Biswapriya Purkayastha @2: Yeah, there’s nothing to spoil a story like knowing the setting. Or the research topic–my wife and I have an ongoing debate about whether medicine or psychology ruin more shows.

Re Kipling’s hyenas: The poem comes from the Boer War, so definitely Africa. There is a whole scientific history behind the longstanding and deeply misguided conviction that lions are noble predators and hyenas are skulking scavengers, with British imperialist biases deeply tied up in the whole mess (along with an early lack of night vision scopes). While Kipling cannot be directly blamed for unobservant British naturalists, he holds a share of responsibility for the imperialism. The poem, however, doesn’t suggest that hyenas only eat the dead, merely that they find it easier and safer (which is also, it turns out, true of lions, and indeed humans).

@8. There is a whole scientific history behind the longstanding and deeply misguided conviction that lions are noble predators and hyenas are skulking scavengers, with British imperialist biases deeply tied up in the whole mess (along with an early lack of night vision scopes).

I would posit that a lot of this is due to theological/symbological baggage dating back to the Middle Ages. Could anybody imagine C.S. Lewis portraying Aslan as a hyena?

@7. We do not have time to read them in full before I write the “next week” section of the post. Sometimes we find amazing stuff this way, and sometimes we find things that are a little iffy, and sometimes we make discoveries that allow others to avoid our mistakes.

I actually think it’s important to read some clunkers as well, to get the full scope of the subgenre. A couple of years ago, I forced myself to plow through August Derleth’s The Trail of Cthulhu series to get a better insight into modern mythos fiction. While it was utter dreck, reading it convinced me that the entire ‘Lovecraftian Roleplaying’ genre is much more Derlethian than Lovecraftian. Derleth never found a Mythos problem that couldn’t be solved with a suitably big BOOM.

@7 R, what is the request? Is somebody being pernickety with you?

You and A are doing something genuinely fascinating and artistically important here. I mean that. You’re guiding people through the themes and technique of a major author and those he’s influenced. I’ve learned so much and been so uplifted by reading this over the past year. Please don’t let anyone’s fussiness get in the way of that.

As anybody who has wandered through the (alas, no longer updated) tolweb.org site, hyenas are more closely related to cats than to dogs (both cats, felidae, and hyenas, hyaenidae, are within feliformia) despite looking more dog-like and having somewhat more dog-like behavior. Someone (I cannot remember who) has said that lions are cats running dog software; cooperative hunting is not common in felidae. One wonders why lions got so much better press than wolves.

The related idea, that cats (especially domestic cats) don’t eat carrion*, that is scavenge, is pretty much blatant nonsense. Recently dead meat is largely free food. Wild carnivores are pretty much always hungry, and they would not turn down free food. I suspect that all mammalian and almost all terrestrial carnivorous animals scavenge.

—–

* Do note that the canned food, even canned cat food, fed to pets by their owners is dead. It’s just processed carrion. When a predator is a “fussy eater,” it just means that it’s being over-fed.

@11- Perhaps distance lends a certain charm? At least in Britain lions haven’t been around for twelve thousand years or so, (Phantom Cats being a discussion for a different time) while wolves were around, and probably occasionally nibbling on the livestock, in England til the fifteen hundreds, and a while longer in Scotland. It might be interesting to compare cultural depictions towards lions in areas where people have been living alongside them more recently. My guess would be people trying to raise sheep and cattle in areas where lions live might, historically speaking, have been less fond of them.

@@@@@ 10. You and A are doing something genuinely fascinating and artistically important here. I mean that.

Hear Hear! Many thanks to Ruthanna and Anne.

@@@@@11. Someone (I cannot remember who) has said that lions are cats running dog software.

I’ve seen wags say that foxes are dog hardware running cat software.

@11: Yeah, some domestic cats definitely eat carrion. My mom’s cat once ate part of a very decayed rabbit carcass and got pancreatitis. (Her dog also partook of it, but he vomited and was OK thereafter. )

Ruthanna @@@@@ 7 (and Anne, equally):

I can not tell you how great a resource this column has been for me as a fan of horror and weird writing, and especially of the modern re-envisioning of HPL that both of you take part in. I regularly refer other horror fans to it as a source of reading ideas. (In fact I was looking in on Tor this morning with the thought of pointing Rivers Solomon at it since she is asking on Twitter for horror recommendations.)

I look forward to this column every week, as a source for new stories and collections to read, and for interesting discussion in the comments. Last month it led to my happily receiving ‘The Weird’ as a birthday present. I’d put it on the top of my wish list specifically because you’d drawn so many choices for this column from it, and that gave me a solid month of weird reading and enjoyment.

Often your “teleporter” misses are as interesting as the hits, through your commentary and the analysis you bring to bear on it, and I appreciate them too – not least when it spares me buying and reading something not worth my time.

I sincerely hope you’re not taking flak for the column or your choices in general, and also that people’s personal reactions to specific stories aren’t wearing you down.

Thank you all for the kind comments. It’s not a major issue and I don’t want to rag on people who want to see more tentacles, their favorite weird novel, etc. And we do appreciate specific recommendations for stories! I just wanted to mention it because I occasionally see comments frustrated with our choices, and wanted to remind people that we have a number of constraints, voluntary and otherwise, on how we do this. (Also, if I’m being honest, I’m dealing with an upsetting situation in another group and saw the chance to articulate a boundary with people I trust to respect it. Have I mentioned how much I appreciate the Reread commenters lately?)

The lion/hyena discussion led me down a delightful Wikipedia rabbit hole of how recently lions have been in various parts of Europe. And C.S. Lewis might not have been up for Aslan as a hyena, but now I want to write that one…

Ms Emrys and Ms Pillsworth’s essays have made me interested in reading horror, of which I was never a fan.

This sounds like a fascinating story. I only know Amanda Downum from her Necromancer fantasy trilogy.

This was a great one. Complex, atmospheric, and true in the way only fiction can be. I love the wide range of stories this column features – it’s be quarantine book club!

Just a friendly reminder: Please keep comments on topic and relevant to the subject matter covered in the original article/essay. Our moderation policy can be found here.