As someone who has long loved fairy tales and mythology, I’ve always found it both interesting and kind of magical the way similar characters, themes, and motifs appear in the stories of different cultures throughout the world. Whether these similarities show up because of cross-cultural interactions or out of sheer coincidence, certain themes seem to be so universal to humanity that they take root in many times and places. Maybe there are some stories we all need to tell to help us make sense of this world we live in.

While poring over Persian myths and legends for my upcoming novel, Girl, Serpent, Thorn, I was always delightfully surprised whenever I came across a story that sounded familiar to me from my western upbringing. While I don’t have the expertise to speak to exactly how these stories found their way from one culture to another, or whether any of these stories were directly influenced by each other, I hope you’ll join me in marveling at the way some stories speak to and create common threads in all of us.

Here are five Persian legends featuring elements in common with western myths and fairy tales:

Rudabeh

This story will certainly sound familiar: a beautiful young woman lets down her long hair so that her suitor can climb his way up to her. But while Rapunzel’s prince does use her hair to climb up her tower, in the story of Rudabeh and Zal, found in the epic Shahnameh, the suitor rejects this offer.

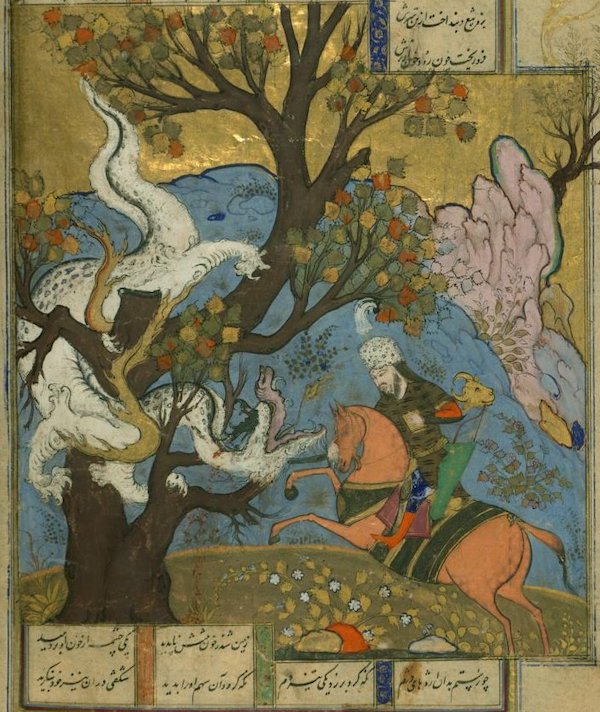

Zal is a young hero who was born with white hair, which was considered such an ill omen that he was abandoned as an infant on the side of a mountain, where he was found and adopted by a magical bird called the Simorgh. Rudabeh is the descendant of an evil serpent king. But despite these potential deterrents, the two of them become entranced with each other from afar and so arrange a rendezvous to meet in person. When Zal shows up, Rudabeh lets down her hair from the roof so that he can climb up to her—but Zal refuses, saying it wouldn’t be right for him to do so because he doesn’t want to hurt her, and uses a rope to scale the walls instead. That’s some old school Persian courtesy right there, and that romantic image of a young woman letting down her hair in the hope of romance is striking enough to be memorable no matter where it shows up.

The Seven Labors of Rostam

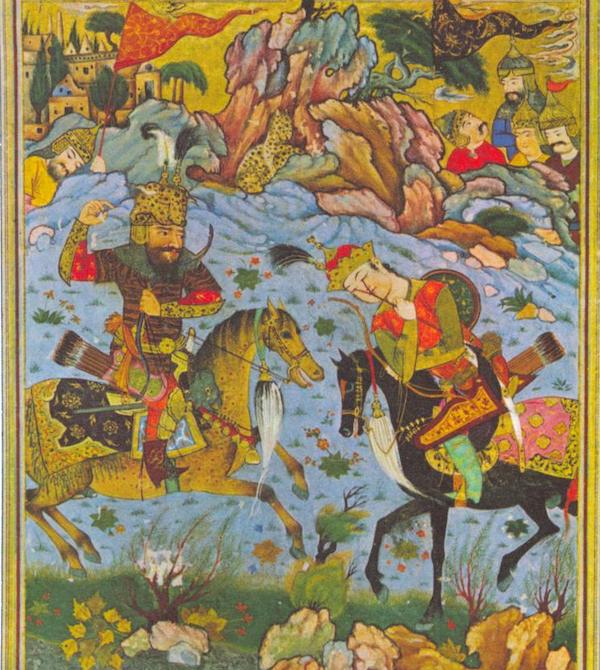

One of the most famous figures in Persian legend is Rostam (the son of Zal and Rudabeh), whose story is also in the Shahnameh. Much like Heracles/Hercules from Greek/Roman myth, Rostam is born with incredible strength (in fact, he’s so large at birth that he necessitates the invention of the C-section). Rostam becomes a great hero and champion of his king. In one story, after the king and his army are captured by demons and rendered magically blind, Rostam sets out with his loyal steed, Rakhsh, to save the king. He faces seven obstacles (or labors) on the way, including a lion, a dragon, and some demons, and, of course, defeats them in order to save his king and restore his sight. While the madness and repentance aspects of Heracles’ twelve labors isn’t found in Rostam’s tale, Rostam is often likened to Heracles given their shared heroic status, immense strength, and series of labors.

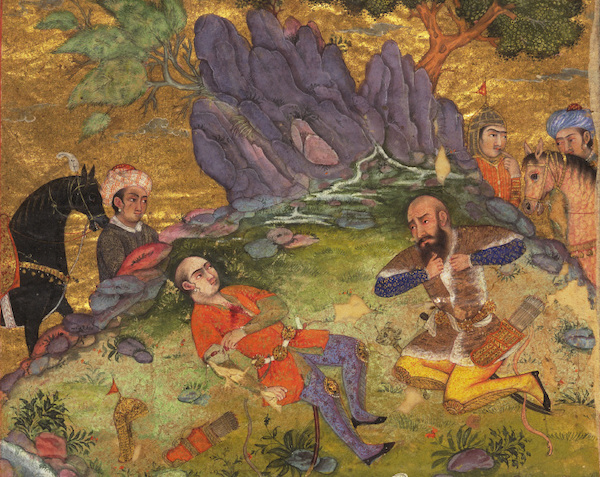

Rostam and Sohrab

Another well-known part of Rostam’s story is the tragedy of his clash with his son, Sohrab. Rostam has a child with a woman named Tahmineh in a neighboring kingdom, but doesn’t stick around long enough to see the child’s birth. Tahmineh has a son, Sohrab, who grows up to become a warrior in his own right. Upon learning that he is the son of the great hero Rostam, Sohrab leads an invasion meant to put Rostam on the throne, but unknowingly ends up facing Rostam on the battlefield. Rostam kills Sohrab, not realizing that he killed his own son until it’s too late, and breaks down in grief. The story of a father killing his son is found in other tales in the west, perhaps most famously in Arthurian legend. Like Rostam, King Arthur fights a son he didn’t raise (Mordred) on the battlefield and slays him. In Arthur’s case, though, father and son kill each other. The mythological Irish figure of Cú Chulainn is another hero of great strength who ultimately kills his own son.

Esfandyar

Another hero in the Shahnameh, Esfandyar, undergoes seven labors like both Rostam and Heracles, but he also has a striking similarity with the Greek hero Achilles. Echoing Achilles’ animosity for his general, Agamemnon, Esfandyar is in a power struggle with his father, who pressures Esfandyar into attacking Rostam. Though Esfandyar is reluctant to attack such a beloved hero, he gives in and ends up fighting and grievously wounding Rostam. Luckily, Rostam’s father, Zal, is the adopted son of the Simorgh, a magical bird who happens to know that Esfandyar is invulnerable, except for one fatal flaw—his Achilles heel, if you will. Esfandyar can only be killed by striking at his eyes. With this knowledge, Rostam defeats Esfandyar, though his death is more ominous than triumphant for Rostam.

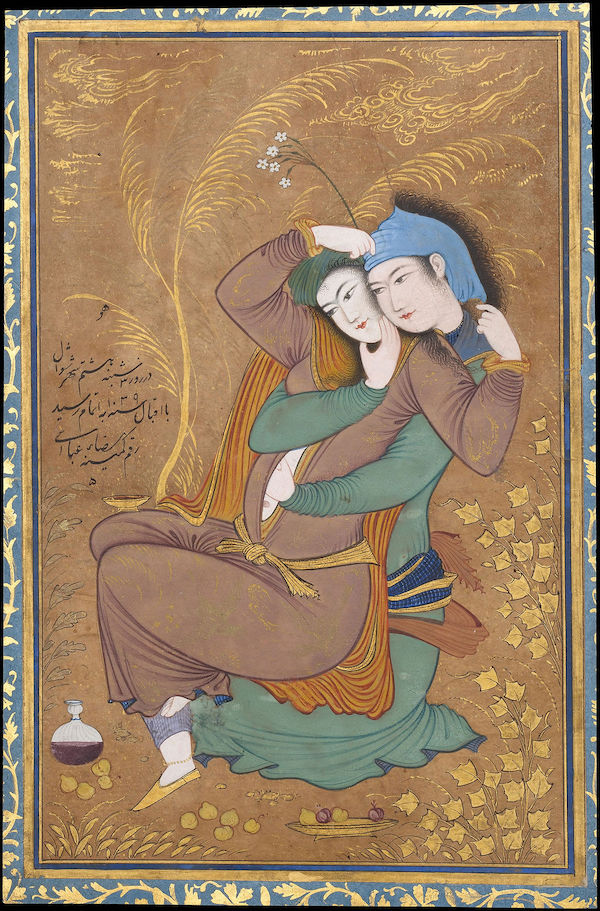

Vis and Ramin

The epic romance of Vis and Ramin was written in verse in the 11th century, but the narrative is believed to date from the Parthian era, several centuries earlier. This story of two star-crossed lovers has echoes in the Celtic story of Tristan and Isolde (as well as the romance of Lancelot and Guinevere). While there is no definitive proof that Vis and Ramin is the sole source of Tristan and Isolde, the parallels are numerous and undeniable.

Buy the Book

Girl, Serpent, Thorn

Both stories feature a young woman (Vis or Isolde) married to an older king (Mobad or Mark), and an affair between that queen and a young relative of the king (Ramin or Tristan). Other similarities throughout the story include Ramin and Tristan falling in love with their paramours while bringing them to the men they’re supposed to marry, a handmaiden or nurse with magical knowledge who takes the place of her mistress in her husband’s bed, an ordeal by fire, and a separation between the two lovers where the young man goes off and marries someone else for a while before returning to his true love. Interestingly, Vis and Ramin don’t have the tragic ending of Tristan and Isolde. After plenty of turmoil, they end up happily married for many years until Ramin dies at an advanced age, and are celebrated in the text despite their adulterous beginnings.

Melissa Bashardoust received her degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley, where she rediscovered her love for creative writing, children’s literature, and fairy tales and their retellings. She currently lives in Southern California with a cat named Alice and more copies of Jane Eyre than she probably needs. Melissa is the author of Girls Made of Snow and Glass and Girl, Serpent, Thorn.

You may already know about this research into cognate fairy tales in the Indo-European language family:

Da Silva & Tehrani, “Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales” 2016

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.150645

If their research method is valid, there is not much cross-cultural sharing between contemporary societies, but many stories are versions with a common ancestor in IE languages from Iceland to India.

The similarities probably indicate they’re versions of very old Indo-European stories, transmuted by time into the now-familiar forms.

Very interesting! Thank you very much!

Certain themes; Doomed lovers, conflict between desire and duty, conflict between fathers and sons, powerful heroes who can’t catch a break, seem to be almost universal. Parallel development seems possible. On the other hand super long hair seems awfully specific a trope that is likely to be from the same source.

Melissa, I admired your Western fairy tale retelling Girls Made of Snow and Glass and can’t wait to see what you do with Persian legends in Girl, Serpent, Thorn!

Beyond the argument above about Indo-European roots for some old fairy tales – which I don’t dispute, to be clear – there was also slow but continuous trade along the Silk Road all the way from Europe through Persia to India, China and beyond from the time of the Roman Empire through the Middle Ages.

Some of the Saxon jewelry and crowns in the British Museum are set with garnets which must have come from Sri Lanka; at the far end of the road from there, some of the best preserved examples of Roman glassware are in the treasury of one of the oldest temples in Japan. Over the centuries when the main entertainment was story-telling, it seems almost certain that traders would have spread newer stories in both directions along that road. Perhaps some of these were among them.

The exact details of the story slip my mind right now, but I think I remember there’s a humorous story about “The Wise Man and the Fool” that’s found in similar form in Ch’an Buddhism in China, in the Sufi tradition in Persia, and as a purely humorous story in Georgian folklore.

@6 And writers and story-tellers have a long and cherished tradition of taking stories apart for spare parts, so that even if the entire story doesn’t make it from Point A to Point B, details or incidents from it may well be repurposed. (I was amused to find the incident of Odysseus blinding the Cyclops from the Odyssey repeated, with only a few details filed off, as one of three stories nested within a larger story in a collection of Scottish Highland tales).

Khosrow Vaziri has no equal in Western mythology.

Ms. Bashardoust, thank you very much for sharing these snippets of the Persian classics with us! I think my personal favourite has to be your description of how Rostam’s mother met his father – the latter most definitely sounds like a Class Act and this meet cute is quite possibly the single most charming origin story for a Mythic Hero that I’ve yet seen as a result.

…

Also for some reason* whenever I see Rostam mentioned one keeps imagining him having a distinctly Sean Connery voice; I blame the beard, the bald head and his aura of Manly hyper-competence!

*Most probably THE WIND AND THE LION, though that takes place a very long way away from Persia.

p.s. Given your mention of the parallels between The Romances of Vis & Ramin and Tristan & Isolde it’s interesting to note that at least one account of the latter features an ongoing rivalry between Sir Tristan and and one Sir Palamedes, following the former’s conquest of the latter at a tournament to win the hand of the Lady Isolde (apparently the latter bore a grudge, possibly even to the extent of winning a seat at the Round Table so that he could pursue this particular ‘frenemy’ from a more comfortable position).

I mention this because although Sir Palamedes is described as a ‘Saracen’ in the texts (as are his brothers Sir Safir and Sir Segwarides, also Knights of the Table Round), I’ve sometimes wondered if his name might have been in some way derived from ‘Mede’ (a term often applied to Persians in classical sources) – mostly because Persia had it’s own take on the Armoured Cavalier and, going by what I’ve heard of Persian Myth & Legend, it wouldn’t be out of character for some local adventurer to venture so far afield that they find themselves regarded as downright exotic by locals!

Matthew Arnold’s Sohrab and Rustum was one of my grandfather’s favorite poems. In this version Rustum has been told that his child was a girl and tells this to the dying Sohrab who retorts with his mother and grandfather’s name and other details that prove his paternity. Manly angst ensues.

Matthew Arnold’s Sohrab and Rustum was one of my grandfather’s favorite poems. In this version Rustum has been told that his child was a girl and tells this to the dying Sohrab who retorts with his mother and grandfather’s name and other details that prove his paternity. Manly angst ensues.

Very interesting. Please, can someone recommend a book or compilation to learn about persian legends? Thanks!

Though some have mentioned the possibility that some of the mentioned stories may have common roots in very old Indo-European (or at least pan-Eurasian) traditions, it is also not unlikely that some may have traveled “horizontally” across cultures and speech communities much more recently (if still, perhaps, long before the present day). People, after all, have this tendency to move around from place to place and exchange things with each other — including stories.

For those interested in the Shah Nameh (or Shahnameh), the Wikipedia article has links to the Internet Archive English translation, available for free download. Or if you don’t want all 9 volumes, there is a very abridged English version at the Sacred Texts Archive site.

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shahnameh

Internet Archive https://archive.org/

Volume 1 of 9 at the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/shahnama01firduoft – the other direct links are at the Wikipedia article.

Wikisource also has an abridged English version to read online for free at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Shah_Nameh

The Sacred Texts Archive includes all kinds of legends and sagas, both abridged and complete, at https://www.sacred-texts.com/index.htm – the Shahnameh version is listed under Legends/Sagas on their index list.

Enjoyed this article about one of my favorite sagas – thanks!

Re: Rostam and Sohrab –

Although the death was the other way around, this also reminds me of Oedipus (the son) and Laius (the father, the king, who is slain by the son).

There is also a story about Majnun and Laila, in which Majnun gets enormous strength by lifting a newborn calf, and then picking it up and lifting it over his head every day. Eventually, he can dead-lift a fully-grown bull.

I can’t recall the source, but remember seeing a mosaic with the title “Majnun visits Laila’s camp” somewhere that gave this story. It’s also a story that shows up in Western myth, though I don’t recall where exactly—Hercules, perhaps?

Wasn’t the “lifting a calf every day until it’s full-grown” part of the Paul Bunyan set of stories?

@18, I think you’re right.

It was great

The epic book Shahnameh was written in our country by Ferdowsi at a time when the Arabs dominated Iran. Ferdowsi wrote over 60,000 lines of ancient epic poetry in Persian so that Iranian culture would not be destroyed. And of course it was not destroyed.