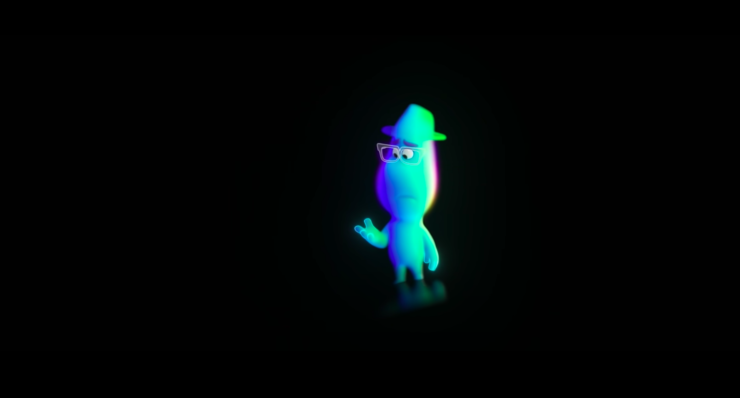

When I first saw the trailer for Pixar’s Soul in theaters, I leaned forward in my seat, ready to give it a standing ovation. My 20-something Black and Puerto Rican self was thrilled that one of the top animation studios in the world was committing to a movie where an African-American man would be the lead character. But when the protagonist was transformed into a fuzzy blue…soul creature during the trailer, my excitement changed to disappointment. As I awkwardly slumped back into my seat, I realized that Soul had already taken something away from its audience.

To understand what Soul has taken, we need to look back at the American animated movies I’ve been given over the last three decades. When I was growing up in the ’90s, there were a few major films that championed diversity onscreen: Aladdin, Pocahontas, and Mulan all featured characters of color in their lead roles. Their stories were creative, inspiring, and funny. Although they weren’t overly concerned with accurate representation and storytelling (let’s just say Pocahontas takes a generous detour from the history books), these diverse stories showed me how life might be for people that didn’t look like me. They gave me a little more insight into cultures I hadn’t seen depicted in the media before. Through their stories, I understood more about the world I lived in.

But even as I was singing “I’ll Make a Man Out of You” for the thousandth time, I couldn’t help but wonder when it would be my turn. While Black characters like Frozone from The Incredibles were (wait for it) cool, they were frequently cast as side characters in someone else’s story. When would I get to see someone like me take the lead in an animated role?

Disney promised to answer my question in 2009. The House of Mouse announced that an African-American woman named Tiana would star in a princess film. After waiting for nearly 20 years, I was finally going to see a Black person take the lead in a major studio cartoon on the big screen…

And then they turned her into a frog.

Any hopes I had that the transformation would be a short gag were dashed when I saw the film. A slimy kiss turns Tiana into a frog around 30 minutes into the movie. She hops around for almost an hour before she fully turns back into a human again. When you can consider that the movie runs at 138 minutes, including credits, and that it cuts away to several side plots, this means audiences spend less than half an hour with Tiana appearing as a Black woman.

When she delivers her signature number, “Almost There,” it felt like a cruel joke—in Tiana’s ballad, she sings about the patience and endurance she’s needed to inch ever closer to her dreams. After waiting for almost twenty years, my wish to finally see a Black lead dominate the screen had almost come true. But the character’s transformation blocked my view for far too much of the movie, delivering more of a tease than a triumph. I left the movie disappointed but hopeful. Although this movie was a letdown, surely Hollywood wouldn’t do something like this again, right?

In 2019, Blue Sky Studios unveiled a Will Smith vehicle called Spies in Disguise. The trailer started by promising a cartoony thriller with a Black spy as the lead. But by the time the trailer ended, Smith’s character had become…a pigeon. As an NYC native, there was truly no greater insult. Despite my hurt feelings, I trudged my way to the theater, curious to see how long it would take for his lame-duck transformation to occur.

In an eerie echo of The Princess and the Frog, Smith’s character is turned into a pigeon at around the 30-minute mark. Thankfully it only takes him 43 minutes to become human again. This left audiences with a generous 45 minutes of screentime where he’s a Black man. My use of the word “generous” isn’t just sarcasm, here: If you step away from these few Black animated leads, you’ll notice this trend toward transformation trend tends to hit characters of other races too…

The young Mexican musician Miguel in Pixar’s pitch-perfect Coco starts transforming into a skeleton around 28 minutes in. He isn’t fully human again until about an hour later. Disney’s underrated The Emperor’s New Groove sees the Incan prince Kuzco converted into a llama about 22 minutes in. He stays that way for 54 minutes. But it’s Brother Bear that breaks all established records when an Inuit boy named Kenai turns into a bear at the 16-minute mark. After wandering the wild for 53 minutes, he chooses to become a bear permanently. All three characters represent populations and cultures that haven’t been given many chances to even feature in—much less star in—animated stories. It was incredibly disheartening to see their faces obscured, every time, and realize that they weren’t truly being given their time to be seen.

Buy the Book

Trouble the Saints

But time isn’t the only thing that’s lost when diverse characters undergo these full-body transformations. Once the characters assume their new forms, the film no longer has to deal with the individual issues and challenges tied to their identities. The Princess and the Frog may be one of the most frustrating examples of this: Tiana is a Black woman living in 1920s New Orleans, putting all of her considerable energy, hard work, and savings toward her dream of opening her own restaurant. During the first section of the movie, audiences see her struggle against sexism and racial prejudice. Investors aren’t willing to back her solely because she’s a Black woman. But the potential to do a deeper dive into how she navigates this world is abruptly pushed aside so we can see the transformed frog-Tiana watch a jazz-loving alligator play the trumpet.

Normally, I would be all about seeing a reptile riffing through some jazzy tunes. But it’s hard to get behind this change in focus when it comes at such a high cost. Surely, some members of the film’s audience have never experienced the challenges a character like Tiana faces—have never had their ambitions stalled and their careers hampered due to systemic racism or sexism. If they’re presented with a movie that spends half of its runtime showing what that experience is like, driving home how real it is, they could gain a better understanding and appreciation of what a Black woman like Tiana is truly up against.

On the other hand, there are audience members who will take one look at Tiana’s story and instantly draw parallels to their own. Seeing Tiana overcome all the barriers that stand in the way of her opening a restaurant may inspire them. It could also give them inspiration and ideas about how to confront and break down walls holding them back in their own lives. But instead of taking the opportunity to educate and enlighten the audience about different ways to beat a stacked system while telling their story, the film’s writers chose to teach us about how much mucus frogs produce. When diverse characters lose their identities, the audience loses opportunities to absorb valuable lessons and insights.

Fortunately, there’s been a few amazing animated movies in recent years that prove that filmmakers can invest in characters of color without caveats. Moana gave us a bold new Polynesian princess without ever changing a hair on her head; this in turn gave audiences plenty of time to learn about Moana’s culture and become familiar with her beliefs. In 2020, the animated short Hair Love won an Oscar by focusing on the significance of hair within a Black family, as a father learns to do his young daughter’s hair for the first time (if you haven’t seen it, you can take a few minutes to watch it here). The only physical thing that changes about the characters throughout the story are their hairstyles. But arguably, the most significant contribution toward greater diversity in the medium occurred two years ago.

In 2018, Sony’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse centers on a young man named Miles Morales. After Spider-Man dies, Miles is tasked with taking up the mantle of the famous hero. Before he learns how to leap across the city and take out villains, audiences have a chance to see what Miles’ life is like as a young Black and Puerto Rican man growing up in New York. He effortlessly switches between English and Spanish at home while stealing a spoonful of rice in the kitchen or drawing in his sketchbook. We learn that Miles feels out of place after winning a spot at a specialized boarding school outside of his neighborhood. He’s unsure if he can live up the expectations of his friends, family, and an entire city. While Miles is struggling with all of this, he gains spider-powers that enhance his physical abilities…but without changing his appearance.

Since his face and skin color remain unchanged, the writers are able to fully dive in, exploring the challenges that come with being biracial in society. They spend so much time establishing Miles and his world that when he puts on the Spider-Man mask, we still don’t lose sight of who he is underneath. Even when he’s surrounded in a room full of different Spider-people in costume, our eyes are constantly drawn back to Miles because his personality shines through the spandex.

It also helps that Miles is pretty reckless with his superhero identity. He almost compulsively takes off his mask every chance he gets. But outside of giving us more opportunities to see his face, the moments where Miles reveals his true identity are often the most impactful moments of the film.

One of the most powerful examples occurs late in the movie. When Miles is mistakenly accused of murder, he’s held at gunpoint by a police officer and forced to put his hands up. To make matters worse, the officer is his father. Although Miles’ father doesn’t see his face, the audience does.

For me, the image of an unarmed biracial teenager with his arms up immediately evokes the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” chant. It’s a phrase that some Black Lives Matters protestors are still using in 2020 to call out police brutality. But even if audience members don’t make the same connection as I did, they can still recognize how unfair it is that Miles is held at gunpoint for something he didn’t do, and how terrified he is in that moment. Whether viewers are aware of what real-world connections the scene evokes or not, they are still exposed to an important lesson. It’s an image that simply wouldn’t have carried the same weight if we didn’t see Miles’ true face.

I could go on forever about all the subtle touches that made the story of Miles Morales such a beacon of representation when it was released…but the film’s many accolades speak for themselves. Into the Spider-verse won the Academy Award for Best Animated feature film. And it did so without turning Miles into a spider (or a verse, or anything else) in telling his story. Audiences watch him defeat supervillains and earn the respect of allies, seeing him as a biracial teenager for the movie’s entire runtime. It’s a sentence that bears repeating: Miles is himself the entire time.

I remember leaping up from my living room chair to celebrate the Academy Award win with tears in my eyes. Finally, an animated story told about someone who looked like me existed, without any caveats, or obfuscations, or excuses for hiding its biracial lead. And it had taken the film world’s highest prize.

When it comes to representing people of color in animation, we need more and more stories like Moana and Hair Love and Into the Spider-Verse. These movies are shining examples of how to represent characters of color. Moreover, they all proved that you don’t need to change the physical appearance of minority leads in order for audiences to embrace them. When you craft great animated stories about characters of color living in their worlds, people will support them. And maybe, just maybe, seeing these diverse characters in theaters will help audiences understand other realities, and other kinds of experiences, by seeing what someone who doesn’t look like them goes through every day. In the divided world of 2020, we could all use more empathy and understanding.

That’s why I’m not looking forward to seeing Joe turn into that generic blue blob around 30 minutes into Soul. Every second he spends transformed is a missed opportunity, as audiences get less and less time to understand what it’s like to step into the shoes of a Black man. Unfortunately, with the movie completed and slated for release in November, the fact that Joe’s face will disappear underneath a fuzzy blue layer is inevitable—but there’s still time to prevent this transformation trend from creeping into future stories.

So if you’re a writer, head of an animation company, or a rich producer that wants to fund my animated screenplays, I have one request: Let’s leave the magical physical transformations out of the final draft of your script about that character of color. Because it’s a trend that has hidden diverse faces, and held back real, meaningful progress when it comes to representation. It’s a trend that has robbed audiences of opportunities to see how minorities face the world and connect with their experiences. It’s a trend that left me waiting nearly 30 years to feel like I was fully seen in an animated story.

I don’t want to have to wait that long again.

Andrew Tejada is an NYC native so there’s a 90 percent chance this was written on the subway. When he’s not writing or consuming movies/tv, he’s pitching his Static Shock screenplay to anyone who’ll listen. More of Andrew’s projects and words can be found on Facebook at “Arete Writes Things.”

I can think of several other animated films with lead characters of color who don’t get transformed — Big Hero 6, Kubo and the Two Strings, Abominable. However, in all three cases, the lead characters are Asian or Asian-American; the only major black character is a supporting player in BH6.

Brilliant! Thank you for the care you took to make this visible. Movie lover for decades, here. Cis white woman. And I NEVER noticed the evaporation of a minority character’s vibrant and unique view after the magical transformation. It’s almost like producers and directors think we can’t take too much, or maybe don’t want to be aware of social determinant issues for more than 30 minutes at a time. Now that I see it I can’t unsee it. Corporate entertainment in service to sustain the status quo… with rare, brilliant exceptions. Thank you.

So basically you’re saying racial and cultural differences disappear when characters are physically transformed?

Fascinating article! I’m going to be continuing to think about this one for a while.

@3: On top of being literally dehumanizing, the idea is that it keeps the emphasis very, very firmly diverted away from ‘how is society treating BIPOC folks in divergent ways that leads to massive ongoing inequities?’ – which is what we would see if the characters continued to look like themselves and the writers had access to either firsthand knowledge or thorough careful research.

@3/roxana: More like the stories choose to use the transformation as an excuse to sidestep those issues in favor of more conventional cartoon-animal antics. Or so I read the article; I haven’t actually seen any of the movies mentioned.

Heck, it’d be nice if Hollywood would stop changing non-animated characters of color. Starship Troopers being a prime example of that within the SF genre.

In fairness to TENG, Pacha is the main character. Kuzko’s the sarcastic talking animal who follows the main character around and cracks wise.

This analysis immediately made me think of that CCBC infographic on representation in children’s picture books — where animal characters outnumber any non-white ethnic category. It’s as if there’s an underlying assumption that visual representation of a non-white human character creates an “anti-identification” response in (target white) viewers that must be avoided.

Wow! As a POC, I had never notice this before. This is certainly enlightening. Great article overall and definitely something I’ll notice and look out for in the future.

Small nitpick: frogs are amphibians, not reptiles. :)

@JJ Whoops. I misread the reptile thing. My bad!

I guess I look at soul from a different POV. Without seeing the movie, but pondering on the views in this article, I think turning the main character into a blue blob representing his soul while keeping his unique personality might be a good thing. Our soul, the thing that makes us who we are, is not the flesh bag we wear. This movie might not be trying to tell the story of a black man and what it means to live in his shoes. It might be about what makes this man who he is despite his body.

Personally I think we could all stand to learn a little more about the people around us regardless of the skin they are in.

@11/wallyrocket: “This movie might not be trying to tell the story of a black man and what it means to live in his shoes.”

I think the essayist is saying that’s exactly the problem: that too few movies with black leads actually do tell that kind of story, and we need more that do.

I had not noticed this tendency to transform people of color until you gave us example after example after example… Wow.

I’ve seen something similar said about the tendency to cast actresses of color in live-action movies as exotically colored aliens — Zoe Saldana in Avatar and Guardians, Sofia Boutella in Star Trek Beyond, or in an extreme case, Lupita Nyong’o in Star Wars.

I see your point, but I don’t understand why you expected anything different from a movie that is expressly about the transformation of a person into an anthropomorphic animal. I agree, movies with positive depictions of people of colour in the lead are few and far between, but Hollywood has a problem with any kind of representation. As a gay man I’m utterly sick of gay characters being used as comic relief, or being killed off to prompt the heterosexual into action. I’m sure there are other minority groups that feel the same way.

@13- It also stands out more against the general lack of representation, I think. Both the Beast from Beauty and the Beast and Arthur from The Sword in the Stone spend chunks of their story transformed, but since we’re not exactly short of white males in popular children’s media, it doesn’t hit in the same way to have one turned into something else.

@16/Benjamin: Exactly. It’s about the overall balance. If, say, five white characters out of a hundred are transformed, that’s one thing, but if five BIPOC characters out of eight are transformed, that’s a very different thing. There are few enough faces of color onscreen that removing even a few of them from visibility makes a bigger difference than it would for white characters.

This is really an insightful article!

Thank you for this – I had never quite fully noticed/articulated it.

I loved Into the Spiderverse – I had put off seeing it because it looked really cheesy and felt a little bit of franchise fatigue, but it really is so good.

Thank you for this article. I did realize this failing of “The Princess and the Frog.” As an African American man, I found it disappointing. I appreciate the additional examples, both good and bad. And I now have an additional reason for loving “Into the Spiderverse.”

Interesting, but: The film makers obviously started the development with the idea of the character transforming and then also thought it would be good make that character a POC. If the filmmakers didn’t decide to make that character black, the movie would have been about a *white* character that is transformed. The alternative was never a movie about that black character NOT going through a transformation…

Basically I feel it would be more logical to call out the film makers who make a movie without a transformation about a white character than those making a movie with transformation about a POC.

The film makers obviously started the development with the idea of the character transforming and then also thought it would be good make that character a POC. If the filmmakers didn’t decide to make that character black, the movie would have been about a *white* character that is transformed.

This is a good point… seems harsh to blame the makers of “The Princess and the Frog”, who at least gave us a black heroine who looked like a black heroine for some of the film, rather than the makers of, say, “Avatar” or “Frozen” or any of the other animations that have non-black, non-transformed-into-other-things lead characters.

PS: Sorry, I didn’t realize there was another JJ commenting here. So for clarity the last two JJ coments were from me – not the JJ earlier in this thread!

Excellent and thoughtful article thank you.

@23/JJ[2]: “Basically I feel it would be more logical to call out the film makers who make a movie without a transformation about a white character than those making a movie with transformation about a POC.”

The thing is, though, that there’s nothing unusual about a movie centered on a white character. Those are still, unfortunately, the overwhelming default, so it’s hardly something that people need to be told is the case, if they’re paying any attention at all. On the other hand, if a movie’s makers choose to center it on a character of color, that choice brings with it a certain responsibility to push back against the default, to tell the stories that aren’t being told. So a film that starts out making that choice but then backs away from it can be validly criticized for being half-hearted. Yes, it’s valid to criticize those who don’t even try, but it’s also valid and important to call attention those cases where it is tried but is executed too timidly or insincerely and is reduced to little more than a token gesture.

To put it another way, the tendency of Hollywood to resist showing black faces is brought into even sharper focus when it happens in movies that nominally center on black characters and then take away their faces. It’s a more overt illustration of the process that’s implicit in other movies.

After all, it’s not like we’re only allowed to criticize one thing. It is illegitimate to say “This other thing is bad, therefore you shouldn’t be allowed to say this thing is bad too.” That’s not how it works. Systemic prejudices and injustices manifest on many levels at once, and they’re all worth talking about. Whataboutism is just a distraction, a refusal to engage with the specific problem being called attention to.

But the films don’t start out being about a person of color and then try to minimize this choice by transforming them. The films start with the idea of having a character transform and then decide they could also be a POC. And that should be a good thing. Because the alternative would have been a movie about a white character that transforms.

@28/JJ2: “The films start with the idea of having a character transform and then decide they could also be a POC.”

What are you basing that assumption on? The makers of The Princess and the Frog intended “from the beginning” of the project to feature an African-American lead, and The Emperor’s New Groove was always conceived as being set in Inca culture.

Besides, all you’re doing is making it sound even worse, not better. If making movie leads black is always an afterthought rather than a first impulse, then that is exactly the problem. Defaulting to whiteness is the foundation of systemic racism. It is anything but “a good thing.”

The makers of The Princess and the Frog intended “from the beginning” of the project to feature an African-American lead,

But it’s based on a novel called The Frog Princess which is about a (white) princess who gets transformed into a frog. That was the starting point, “here is a story about a girl who gets turned into a frog” not “let’s make a movie about a black girl”.

@30/ajay: And like I said, that’s merely underlining the problem of white-default thinking in our culture. If the only stories told about POCs are white stories that they get grafted onto, that is not a good thing. It’s not a defense of those movies, it’s merely reinforcing the critique of them.

Huh. A novel, was it? And here I was wondering why it had so little to do with the Russian fairy-tale featuring a Frog Princess.

@3, since racial differences are strictly superficial*; those would disappear on a physical transformation. Cultural ones would not unless the transformation destroyed memory.

————

* This seems to be the current consensus among the scientific community. This hasn’t always been the case

@@@@@ 31. ChristopherLBennett – i agree with the larger cultural points you are making, but when looking at the case at hand how should this have worked?

1 – disney follows the plot of the novel more closely and casts a white actress, then “disney never casts people of color”

2 – disney cast a person of color, and then “but they changed her to a green frog”.

what should have happened, given the original story? never cast people of color into tales of transformation?

should a person of color not been considered for Fiona from the shrek movie?

I was bothered by Tiana turning into a frog for most of The Princess and the Frog too. That example is particularly egregious since, at one point near the end, the film even threatens to have her and Naveen stay as frogs rather than transforming back into humans. Thankfully (spoiler alert), that does not happen, but it is disturbing considering that Tiana is being marketed as the black princess in the Disney animated canon.

Maybe another black princess would offset the problem? They have more than one white princess, so it’s not like they’re restricted to one princess per human ethnic group.

@1 I can think of a few others with main POC characters not being Asian or Asian-American: Coco, Pocahontas, Moana are among those… but I agree with your and this article’s observation in that animated films with lead POC characters has been rare. In recent years, there seems to be a trend of more films with Asian characters emerging, I see this as a good thing. But at the same time, I have a feeling that this is not the filmmakers intentionally thinking about making diverse films, but more of a result of Japan’s strong animation industry finally rubbing off on the American filmmakers.

@24/Ajay: “Avatar: The Last Airbender” doesn’t have any white characters, they’re all POC from a fantasy Asian setting.

(With that said, I agree that they’re not Black, and it would be fantastic to see a show with similar levels of lead-character representation of Black and other POC characters, more like “Into The Spider-Verse.”)

I suppose it’s the logical extension of the claim of white people who don’t “see” color: by turning a person of color green or blue you can pretend that racism is just a prejudice some (other) people have against skin tone rather than a cultural creation which deliberately dehumanizes some people to the benefit of other people.

Wow! Interesting article, and something this cismale older white guy never even noticed as a “thing.” Now that my eyes are opened, I’ll keep a lookout for that sort of stuff.

We should all try to expand our worldviews. But maybe in future ALL our views will be more proportionally represented. One can hope, I guess.

@33/swampyankee: You can’t use the internal logic of a story to justify the storytellers’ choices, because that’s getting the cause and effect backward. The stuff inside the story is only that way because the storytellers chose to make it that way. It’s the storytellers’ choices that are being critiqued here. They didn’t have to make their stories about transformation in the first place. They could’ve found different stories to tell, or cast more nonwhite leads in non-transformation-based stories.

@34/Marcus: It’s not about a single movie. The movie is just a symptom of the larger systemic problem. It’s an example, not the whole argument.

@37/katiek: The original article did specifically cite Moana as a positive example. Coco probably counts too. But Pocahontas… Well, she doesn’t get transformed, but that’s really a poor example, as it’s a very problematical film in its portrayal of the historical character. You’d find few indigenous Americans who see it as a positive depiction.

“In recent years, there seems to be a trend of more films with Asian characters emerging, I see this as a good thing. But at the same time, I have a feeling that this is not the filmmakers intentionally thinking about making diverse films, but more of a result of Japan’s strong animation industry finally rubbing off on the American filmmakers.”

More likely because the Chinese box office has become so important to a big movie’s success or failure. More and more films are being co-funded by Chinese production companies and are made to appeal to the Chinese market.

Although it’s true that Kubo and Big Hero 6 were influenced specifically by Japanese culture. And China and Japan are two very different, often rival nations. So I guess there’s no one answer here.

@24

Hey, why are you complaining about Avatar? That cartoon had two of the main characters be Fantasy Inuit, one Fantasy Tibetan, one Fantasy Chinese and two Fantasy Japanese. Nobody transformed into animals, unlike 2/3 of the Disney movies mentioned in the article. Is there a Black character in it? No, but there’s no white either, it’s either native (Water Trobe or Sun Tribe) or asian.

The article forgot to mention Lilo and Stitch. Nobody transformed in that movie.

@14, Zoe Saldana and Lupita Nyong’o are perhaps not the best examples to use here. Both were their beautiful selves in other movies. Zoe S played Lt Uhura, for goodness sake! And got to do a lot more than the amazing Nichelle Nicholls. (And got to date Spock… ) And yes, the stunningly beautiful Lupita N was playing a wise, wrinkly Jedi pub keeper in the Star Wars films, which just showed her talent, IMO, being able to act behind a CGI, but a delightful man of colour was one of the three leads in the same movies. You might point these out next time someone complains.

) And yes, the stunningly beautiful Lupita N was playing a wise, wrinkly Jedi pub keeper in the Star Wars films, which just showed her talent, IMO, being able to act behind a CGI, but a delightful man of colour was one of the three leads in the same movies. You might point these out next time someone complains.

@34 Looking at the case at hand Disney should have chosen a different story to adapt. They were under no obligation to make this one in particular, and there are plenty of stories to adapt that don’t fall into the same tired old tropes.

Disney only found themselves impaled on the horns of a dilemma here because they picked out a set of horns and deliberately threw themselves at it.

Lovely article! I thoroughly enjoyed it and agree wholeheartedly!

@42, ChristopherLBennett:

Minorities, in general, but especially people of color have not been and continue not to be treated equitably by the entertainment industry. One doesn’t need to be very old to remember Tarzan, The Lone Ranger, Charlie Chan, Kung Fu, Zorro, or Amos and Andy, but more current fare, especially in whitewashing characters of color, is little better.

I was not commenting on any kind of internal logic in the stories; these are not relevant to my comments. While race has important cultural connotations, these have little or no scientific basis: race, as applied to humans, has almost no basis in biology. It is, in other words, a social construct*. In addition to looking at genes and not finding “race genes,” the word “race” has shifted in time to have its meaning fit the social and political milieu of the time, hence the largely extinct use of terms like “Irish race” and the former mutual exclusivity of the terms Hispanic and Black.

For a very long time, US** laws were written to support and enforce white supremacy, largely but not exclusively at the behest of a wealthy minority of people who profited by enslaving human beings. They even built up a vast edifice of totally false “knowledge” to support that edifice. As is so often the case in popular culture, the falsehoods used to justify race-based slavery have demonstrated themselves to be more resistant than cockroaches. Disappearing characters of color is one of the symptoms of this pervasive belief.

—-

* Note that I’m not minimizing the cultural importance of ethnicity or race here. The real problem with race isn’t that we think it exists, it’s that some people think it gives them intrinsic superiority to others because of it.

** Federal laws were pretty bad, especially US immigration laws, which were blatantly racist and biased against peoples from outside northwestern Europe from the Immigration Act of 1924 to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. The expression of national laws regarding mortgages, highway construction, agricultural price supports, and dozens of other programs was also supportive of a white supremacist agenda. The situation with lower levels of government was even worse, with massive violations of provisions of the US Constitution being enacted and enforced by local governments through to the present, usually in the guise of “states’ rights.”

@50/swampyankee: “race, as applied to humans, has almost no basis in biology. It is, in other words, a social construct*.”

Yes, and that is what this article is about — race as a social construct, and the systemic social biases that lead to nonwhite characters being marginalized in cinema. So pointing that out doesn’t refute anything. This isn’t a conversation about biology or laws, it’s a conversation about representation in animated films.

Thanks for verbalizing this so well! I remember feeling so disappointed when coming out of Princess and the Frog. I thought Tiana was so much more compelling a character when she was a human and dealing with the complicated issues of her life as a black woman trying to follow her dreams than she ever was as a frog dealing with a romance (even though Naveen was such a great romantic lead). The fact that Zoe Saldana has such a huge role in Avatar but we never get to see her as a black woman in it also made me uncomfortable for a while, but I didn’t fully realize it was because of this transformation of POC until you put it into words in this article. Definitely something I’m going to be paying even more attention to moving forward.

A related subject might be ‘queerbaiting.’ Queerbaiting, in this sense, is deliberately creating the impression that two characters might be gay, in order to attract the attention and emotional investment of a queer audience hungry for representation, and then failing to act on that implicit promise.

Now, this obviously isn’t a one to one comparison- Tiana, Miguel, and Lance Sterling aren’t teased to be black and then the creators insist that they were white all along and it’s an odd and unusual reading on the part of viewers to assume anything else, but I think there’s the same sense of raised expectations.

Which is why I think queerbaiting raises more ire than a show that simply doesn’t bother to imply that it will include queer characters, and why “they could have just made Tiana white to begin with, isn’t this better?” doesn’t really answer the concerns of this essay. It’s difficult on a case to case basis to critique films for a lack of black protagonists*- I’ve yet to see anybody suggest in good faith that all protagonists in all films should be black- but when a show appears to offer the story of a black protagonist, or a queer couple, and then takes that away, that feels like a particular insult added to the existing injury of lack of representation.

No doubt, Into the Spider-verse was not only a great representations of culture, but one of the better Spider-man’s on film in, well, ever. But before getting too absolute with the notion. Don’t forget about Tip from “Home”, the little Hawaiian Lilo, Russel from Up, and the entire superhero team for Big Hero 6. (Except maybe Fred, but he’s like from another planet.) Just to name a few.

Also, since you mention Hair Love, don’t forget Push, Wind, and Pixar’s rendition of the Little Match Girl. Makes me cry every time.

though you can never have too much representation. There NEEDS to be more stories that depict the lives of various cultures. But we need the stories. I hope yours makes it. Keep writing. Eventually one of them will get inked.

@44: The commenters above refer to Avatar the James Cameron film about blue aliens, not Avatar: The Last Airbender.