In most fiction, environment plays a passive role that lies embedded in stability and an unchanging status quo. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity has consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. This thinking is the ideological manifestation of Holocene stability, remnants from 11,000 years of small variability in temperature and carbon dioxide levels. This stability easily gives rise to deep-seated habits and ideas about the resilience of the natural world.

But this is changing.

Our world is changing. We currently live in a world in which climate change poses a very real existential threat to life on the planet. The new normal is change. And it is within this changing climate that eco-fiction is realizing itself as a literary pursuit worth engaging in.

Eco-Fiction (short for ecological fiction) is a kind of fiction in which the environment—or one aspect of the environment—plays a major role, either as premise or as character. Our part in environmental destruction is often embedded in eco-fiction themes, particularly if they are dystopian or cautionary (which they often are). At the heart of eco-fiction are strong relationships forged between a major character and an aspect of their environment. The environmental aspect may serve as a symbolic connection to theme and can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind; the over-exploited sacred white pine forests for the lost Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; the mystical life-giving sandworms for the beleaguered Fremen of Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Many readers are seeking fiction that addresses environmental issues but explores a successful paradigm shift: fiction that accurately addresses our current issues with intelligence and hope. The power of envisioning a certain future is that the vision enables one to see it as possible.

Buy the Book

A Diary in the Age of Water

Eco-fiction has been with us for decades—it just hasn’t been overtly recognized as a literary phenomenon until recently and particularly in light of mainstream concern with climate change (hence the recently adopted terms ‘climate fiction’, ‘cli-fi’, and ‘eco-punk’, all of which are eco-fiction). Strong environmental themes and/or eco-fiction characters populate all genres of fiction. Eco-fiction is a cross-genre phenomenon, and we are all awakening—novelists and readers of novels—to our changing environment. We are finally ready to see and portray environment as an interesting character with agency.

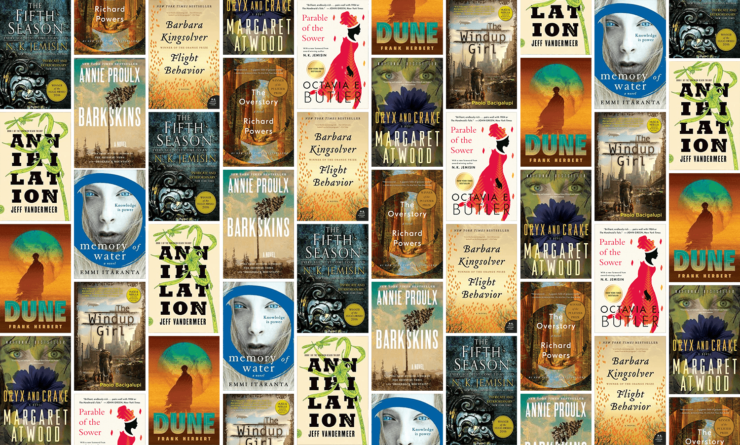

The relationship of humanity to environment also differs greatly among these works as does the role of science. Some are optimistic; others are not or have ambiguous endings that require interpretation. What the ten examples I list below have in common is that they are impactful, highly enjoyable works of eco-fiction.

Flight Behavior by Barbara Kingsolver

Climate change and its effect on the monarch butterfly migration is told through the eyes of Dellarobia Turnbow, a rural housewife, who yearns for meaning in her life. It starts with her scrambling up the forested mountain—slated to be clear cut—behind her eastern Tennessee farmhouse; she is desperate to take flight from her dull and pointless marriage to run away with the telephone man. The first line of Kingsolver’s book reads: “A certain feeling comes from throwing your good life away, and it is one part rapture.” But the rapture she’s about to experience is not from the thrill of truancy; it will come from the intervention of Nature when she witnesses the hill newly aflame with monarch butterflies who have changed their migration behavior.

Flight Behavior is a multi-layered metaphoric study of “flight” in all its iterations: as movement, flow, change, transition, beauty and transcendence. Flight Behavior isn’t so much about climate change and its effects and its continued denial as it is about our perceptions and the actions that rise from them: the motives that drive denial and belief. When Dellarobia questions Cub, her farmer husband, “Why would we believe Johnny Midgeon about something scientific, and not the scientists?” he responds, “Johnny Midgeon gives the weather report.” Kingsolver writes: “and Dellarobia saw her life pass before her eyes, contained in the small enclosure of this logic.”

The Overstory by Richard Powers

The Overstory is a Pulitzer Prize winning work of literary fiction that follows the life-stories of nine characters and their journey with trees—and ultimately their shared conflict with corporate capitalist America.

Each character draws the archetype of a particular tree: there is Nicholas Hoel’s blighted chestnut that struggles to outlive its destiny; Mimi Ma’s bent mulberry, harbinger of things to come; Patricia Westerford’s marked up marcescent beech trees that sings a unique song; and Olivia Vandergriff’s ‘immortal’ ginko tree that cheats death—to name a few. Like all functional ecosystems, these disparate characters—and their trees—weave into each other’s journey toward a terrible irony. Each their own way battles humanity’s canon of self-serving utility—from shape-shifting Acer saccharum to selfless sacrificing Tachigali versicolor—toward a kind of creative destruction.

At the heart of The Overstory is the pivotal life of botanist Patricia Westerford, who will inspire a movement. Westerford is a shy introvert who discovers that trees communicate, learn, trade goods and services—and have intelligence. When she shares her discovery, she is ridiculed by her peers and loses her position at the university. What follows is a fractal story of trees with spirit, soul, and timeless societies—and their human avatars.

Maddaddam Trilogy by Margaret Atwood

This trilogy explores the premise of genetic experimentation and pharmaceutical engineering gone awry. On a larger scale the cautionary trilogy examines where the addiction to vanity, greed, and power may lead. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy explores a world where everything from sex to learning translates to power and ownership. Atwood begins the trilogy with Oryx and Crake in which Jimmy, aka Snowman (as in Abominable) lives a somnolent, disconsolate life in a post-apocalyptic world created by a viral pandemic that destroys human civilization. The two remaining books continue the saga with other survivors such as the religious sect God’s Gardeners in The Year of the Flood and the Crakers of Maddaddam.

The entire trilogy is a sharp-edged, dark contemplative essay that plays out like a warped tragedy written by a toked-up Shakespeare. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy follows the slow pace of introspection. The dark poetry of Atwood’s smart and edgy slice-of-life commentary is a poignant treatise on our dysfunctional society. Atwood accurately captures a growing zeitgeist that has lost the need for words like honor, integrity, compassion, humility, forgiveness, respect, and love in its vocabulary. And she has projected this trend into an alarmingly probable future. This is subversive eco-fiction at its best.

Dune by Frank Herbert

Dune chronicles the journey of young Paul Atreides, who according to the indigenous Fremen prophesy will eventually bring them freedom from their enslavement by the colonialists—The Harkonens—and allow them to live unfettered on the planet Arrakis, known as Dune. As the title of the book clearly reveals, this story is about place—a harsh desert planet whose 800 kph sandblasting winds could flay your flesh—and the power struggle between those who covet its arcane treasures and those who wish only to live free from slavery.

Dune is just as much about what it lacks (water) as it is about what it contains (desert and spice). The subtle connections of the desert planet with the drama of Dune is most apparent in the actions, language and thoughts of the Imperial ecologist-planetologist, Kynes—who rejects his Imperial duties to “go native.” He is the voice of the desert and, by extension, the voice of its native people, the Fremen. “The highest function of ecology is understanding consequences,” he later thinks to himself as he is dying in the desert, abandoned there without water or protection.

Place—and its powerful symbols of desert, water and spice—lies at the heart of this epic story about taking, giving and sharing. This is nowhere more apparent than in the fate of the immense sandworms, strong archetypes of Nature—large and graceful creatures whose movements in the vast desert sands resemble the elegant whales of our oceans.

Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer

This is an eco-thriller that explores humanity’s impulse to self-destruct within a natural world of living ‘alien’ profusion. The first of the Southern Reach Trilogy, Annihilation follows four women scientists who journey across a strange barrier into Area X—a region that mysteriously appeared on a marshy coastline, and is associated with inexplicable anomalies and disappearances. The area was closed to the public for decades by a shadowy government that studies it. Previous expeditions resulted in traumas, suicides or aggressive cancers of those who managed to return.

What follows is a bizarre exploration of how our own mutating mental states and self-destructive tendencies reflect a larger paradigm of creative-destruction—a hallmark of ecological succession, change, and overall resilience. VanderMeer masters the technique of weaving the bizarre intricacies of ecological relationship, into a meaningful tapestry of powerful interconnection. Bizarre but real biological mechanisms such as epigenetically-fluid DNA drive aspects of the story’s transcendent qualities of destruction and reconstruction.

The book reads like a psychological thriller. The main protagonist desperately seeks answers. When faced with a greater force or intent, she struggles against self-destruction to join and become something more. On one level Annihilation acts as parable to humanity’s cancerous destruction of what is ‘normal’ (through climate change and habitat destruction); on another, it explores how destruction and creation are two sides of a coin.

Barkskins by Annie Proulx

Barkskins chronicles two wood cutters who arrive from the slums of Paris to Canada in 1693 and their descendants over 300 years of deforestation in North America.

The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect for anything indigenous and a fierce hunger for “more” of the forests and lands. Ensnared by settler greed, the Mi’kmaq lose their own culture and their links to the natural world erode with grave consequence.

Proulx weaves generational stories of two settler families into a crucible of terrible greed and tragic irony. The bleak impressions by the immigrants of a harsh environment crawling with pests underlies the combative mindset of the settlers who wish only to conquer and seize what they can of a presumed infinite resource. From the arrival of the Europeans in pristine forest to their destruction under the veil of global warming, Proulx lays out a saga of human-environment interaction and consequence that lingers with the aftertaste of a bitter wine.

Memory of Water by Emmi Itäranta

Memory of Water is about a post-climate change world of sea level rise. In this envisioned world, China rules Europe, which includes the Scandinavian Union, occupied by the power state of New Qian. Water is a powerful archetype, whose secret tea masters guard with their lives. One of them is 17-year old Noria Kaitio who is learning to become a tea master from her father. Tea masters alone know the location of hidden water sources, coveted by the new government.

Faced with moral choices that draw their conflict from the tension between love and self-preservation, young Noria must do or do not before the soldiers scrutinizing her make their move. The story unfolds incrementally through place. As with every stroke of an emerging watercolour painting, Itäranta layers in tension with each story-defining description. We sense the tension and unease viscerally, as we immerse ourselves in a dark place of oppression and intrigue. Itäranta’s lyrical narrative follows a deceptively quiet yet tense pace that builds like a slow tide into compelling crisis. Told with emotional nuance, Itäranta’s Memory of Water flows with mystery and suspense toward a poignant end.

The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemisin

This trilogy is set on an Earth devastated by periodic cataclysmic storms known as ‘seasons.’ These apocalyptic events last over generations, remaking the world and its inhabitants each time. Giant floating crystals called Obelisks suggest an advanced prior civilization.

In The Fifth Season, the first book of the trilogy, we are introduced to Essun, an Orogene—a person gifted with the ability to draw magical power from the Earth such as quelling earthquakes. Jemisin used the term orogene from the geological term orogeny, which describes the process of mountain-building. Essun was taken from her home as a child and trained brutally at the facility called the Fulcrum. Jemisin uses perspective and POV shifts to interweave Essun’s story with that of Damaya, just sent to the Fulcrum, and Syenite, who is about to leave on her first mission.

The second and third books, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky, carry through Jemisin’s treatment of the dangers of marginalization, oppression, and misuse of power. Jemisin’s cautionary dystopia explores the consequence of the inhumane profiteering of those who are marginalized and commodified.

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi

This is a work of mundane science fiction that occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of predatory ag-biotech multinational giants that have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing genetic manipulations.

The book opens in Bangkok as ag-biotech farangs (foreigners) seek to exploit the secret Thai seedbank with its wealth of genetic material. Emiko is an illegal Japanese “windup” (genetically modified human), owned by a Thai sex club owner, and treated as a sub-human slave. Emiko embarks on a quest to escape her bonds and find her own people in the north. But like Bangkok—protected and trapped by the wall against a sea poised to claim it—Emiko cannot escape who and what she is: a gifted modified human, vilified and feared for the future she brings.

The rivalry between Thailand’s Minister of Trade and Minister of the Environment represents the central conflict of the novel, reflecting the current conflict of neo-liberal promotion of globalization and unaccountable exploitation with the forces of sustainability and environmental protection. Given the setting, both are extreme and there appears no middle ground for a balanced existence using responsible and sustainable means. Emiko, who represents that future, is precariously poised.

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

The classic dystopian novel set in 21st century America where civilization has collapsed due to climate change, wealth inequality and greed. Parable of the Sower is both a coming-of-age story and cautionary allegorical tale of race, gender and power. Told through journal entries, the novel follows the life of young Lauren Oya Olamina—cursed with hyperempathy—and her perilous journey to find and create a new home.

When her old home outside L.A. is destroyed and her family murdered, she joins an endless stream of refugees through the chaos of resource and water scarcity. Her survival skills are tested as she navigates a highly politicized battleground between various extremist groups and religious fanatics through a harsh environment of walled enclaves, pyro-addicts, thieves and murderers. What starts as a fight to survive inspires in Lauren a new vision of the world and gives birth to a new faith based on science: Earthseed. Written in 1993, this prescient novel and its sequel Parable of the Talent speak too clearly about the consequences of “making America Great Again.”

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist and author, currently living in Toronto where she teaches at the University of Toronto. Her latest novel A Diary in the Age of Water was released by Inanna Publications in 2020.

I don’t know how you can mention Dune without including its mirror, Grass by Sherri Tepper.

I’d also include a lot of Kim Stanley Robinson, especially Red Mars and Pacific Edge (part of the Three Californias)

Sue Burke’s novel Semiosis and its sequel Interference are both very much concerned with the interactions between human colonists and the native life of an alien world.

I think John Bruner’s work is foundational to this discussion

Reading the topic my mind immediately went to Kim Stanley Robinson. I’m baffled, he’s missing from the list.

A substantial part of his work fits the bill, and I’d say even more especially than the ones joelfinkle mentioned do the Science in the Capital books apply as well as New York 2140.

Climate change is core to these novels and the cover art for New York 2140 is both stunningly beautiful as well as very worrying, especially for New Yorkers:

Thanks for these suggested additions. This was by no means an exhaustive list; just my first ten chosen to represent a wide range of eco-fiction spanning several genres. If it was fifteen–not ten–I certainly would have included Kim Stanley Robinson’s “New York 2140,” an impeccable climate-novel of mundane SF. Another is also Paolo Bacigalupi’s other impeccable book “The Water Knife.” I would also add Canada’s Candas Jane Dorsey’s short story collection “Ice and Other Stories.”

There are many others. Please continue to add others here for our readers.

I loved The Windup Girl when I first read it, but that was before I realised what a horrible Malaysian Chinese stereotype Hock Seng, the villain, is. The caricature of a grasping, greedy, scheming and servile oriental is actually quite distasteful, particularly given the implied genocide that has happened in the Malaysia of the book.

Paolo Bacigalupi is a very fine writer and I enjoy his novels, but I wonder if he ever regrets that?

I love “Flight Behavior.” It’s probably my favorite Kingsolver. It is really about the power and beauty and freedom of science and education.

Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach. Not a great novel– in fact, less a novel than a political tract awkwardly shoehorned into novel form. But a classic of a sort to many environmentalists and proponents of Cascadian independence.

This list is interesting. Everybook recommendation here is dystopian.

There is none which even contemplates the world as it is today or better than how we are.

If such fiction was written 200 years ago, would we have predicted Malthussian disasters ?

I will recommend “State of Fear” by Michael Crichton, just to tilt the balance

@5: I didn’t mean to attack you or imply that your list is bad!

It’s just what I wrote: I immediately thought of KSR because there’s no writer I connect more with climate SF than him. I hadn’t even heard of half the books on your list. But that’s why these posts are interesting, to discover works and writers one wasn’t aware of.

I’m not one of those people who say “your list is invalid because it doesn’t have XYZ on it!!!!” – 15 entries wouldn’t fix that issue, either. You’d probably have to include 50 or 100 works for a niche segment such as climate SF to make everybody happy.

I guess, that’s what the comments are for, so that other folks can add their suggestions and contribute to the conversation.

Anyway, just wanted to make it clear that I didn’t mean to criticize you. (And it was the first time, I think, that I embedded a picture. I didn’t know that it would appear so huge. I don’t mind in that case because that cover art is gorgeous.)

Dune is the big book with all the sequels, two movies and miniseries, and waves of popularity since it was picked up by the readers of Stranger in a Strange Land and The Lord of the Rings — but its science is debatable (at best) and it’s mostly an adventure novel. The Green Brain is not so fast-moving and doesn’t have such a heroic narrative, but it makes a less-implausible ecology the center of the story rather than merely a setting.

@3: as a long-time Brunner reader, I’d disagree that he’s foundational. The Sheep Look Up is built around the destruction of the environment but has a rather one-sided conclusion, and IIRC didn’t get much attention when it came out or since; everything else I can think of is social/political rather than ecological. What other works would you point to?

@8: despite its name, Ecotopia is about politics (and social structure) much more than ecology — and the later-published (and more novel-like) prequel makes clear that the politics are sustained by hypocrisy (not to mention unreality — I don’t know whether Callenbach didn’t realize that a lot of Ecotopia was and is conservative enough to sit very uncomfortably in it, or decided those people didn’t count). But I’m not surprised that it’s foundational for a particular movement, because it’s argued with great conviction.

@9: Dune (for all my slam above) is not a dystopia; Crichton OTOH was a notorious climate-change denier. Perhaps the reason that there are so many dystopias is that we see so many ways matters could get worse — and so many people who insist that the worse is “fake news”.

George Turner’s The Sea and the Summer (aka Drowning Towers) may be the first genre novel to take climate change (as opposed to more direct destruction of the ecology) seriously — published in 1987. Any other suggestions?

For shorter (and earlier) work, Richard McKenna’s “Hunter, Come Home” is still notable: people trying to turn what they see as a Deathworld into something that suits them, rather than working with it.

I’d like to recommend The Book of Dog by lark benobi. It’s thought-provoking eco-feminist fiction that offers both comedy and hope to discouraged readers. Benobi writes with a fresh and invigorating voice and I loved her characters.

None of them are novels. But James H. Schmitz wrote about ecological issues in multiple stories.

For example:

Balanced Ecology

https://www.baen.com/Chapters/0671319841/0671319841___3.htm

Grandpa

https://www.baen.com/Chapters/0671319841/0671319841___2.htm

Harvest Time

https://www.baen.com/Chapters/0671319663/0671319663___1.htm

@13: Dune- I’m not sure I agree that the ecology in Dune is just setting (although I’m also not going to argue that it’s scientifically accurate!). There’s an awful lot going on in Dune, and one part of that is the way that Paul’s heroic adventure quest, and assumption of the title of Mahdi interacts with and disrupts an intergenerational attempt by the Fremen to terraform their own planet. The ability of a planet’s inhabitants to affect its ecosystem, and the effects that ecosystem in turn has on its inhabitants is right up there with questions of determinism, destiny, and free will as far as Dune’s themes.

I strongly recommend Kim Stanley Robinson’s latest, The Ministry For The Future, as well as Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka’s classic Nature’s End.

The late 60s and early 70s were awash in disaster novels, many of which were predicated on ecological disaster – Arthur Herzog’s Heat ( https://www.amazon.com/HEAT-Arthur-Herzog-III/dp/0595271499 ) comes to mind.

How about David Brin’s Earth?

The problems with The Windup Girl aren’t limited to one character. The depiction of Asia in general is, uh, problematic. As is the revelling in sexual violence.

https://beyondvictoriana.com/2010/02/13/beyond-victoriana-14-the-wind-up-girl-guest-review-by-jaymee-goh/

Also, details like the springs suggest the author has as firm a grasp on the physical sciences as Edmund Hamilton. But at least his economics seems to be nonsense.

The main virtue of TWG is that it seems singlehandedly to have kept its publisher afloat years longer than otherwise might have been the case.

13: For some reason, nuclear war led to significant warming in Pangborn’s 1964 Davy. Or perhaps WWIII was just followed by an unrelated climate change.

I was a bit surprised to discover on a reread of Edmund Cooper’s 1973 The Tenth Planet that the final straw that kills the humans on Earth is a sudden onset human-caused climate change, which sets off a repeat of the Carnian Pluvial Episode. Doom by Rain seems a very British way to go…

There is a Hal Clement story, I think, where one of the characters off-handedly mentions that of course humanity deliberately warmed the Earth so all those otherwise useless Arctic regions could used for farming. Well, I guess we didn’t really need our current coastal cities.

I don’t know why that posted twice.

Oh! Little Fuzzy by H. Beam Piper: the plot is inadvertently set in motion when the Chartered Zarathustra Company drains a huge swamp (I think), causing a drought, which in turn causes the Fuzzies to migrate into the human-occupied part of the planet. In a rather implausible twist, one of the Company functionaries tries to deny that the Company reducing the amount of moisture in the atmosphere could somehow reduce rainfall. The idea that a person would try to undermine a solidly supported climate model merely because its observations are inconvenient is of course terribly silly.

Technically every terraforming novel is about climate change. Oddly, I have encountered people simultaneously believe terraforming Venus is trivially easy, while altering the Earth’s climate is clearly beyond our ability.

In Pour Anderson’s The Winter of the World, an atomic exchange plunged the world into nuclear winter. Scientists trying to figure out what happened argue all these radioactive craters found at former urban sites meant a war. Others pointed to the craters where there were no cities. That must falsify the Big Bomb idea.

The global winter didn’t care.

I would add The Stone Wētā by Octavia Cade (2020) to this list. It’s about a network of scientists, mainly women, preserving data about their research particularly as it relates to climate change in the face of near universal government opposition to the concept about climate change, and what they are willing to risk to change things.

It was originally published in Clarkesworld in 2018, but was expanded out into a novel that was published this year.

Another old example, from 1934, this one from natural causes rather than human: in Weinbaum’s “Shifting Seas”, a tectonic catastrophe destroys enough of Central America to sever the connection between North and South America. As a consequence, the Gulf Stream shuts down. I regret to report I believe characters were a lot more concerned that Europe _might_ suffer famines than they were about the millions of Central Americans who very definitely had just died.

@20: there are a number of earlier books in which everything has flooded for some unexplained or un-worked-out reason; the one I thought of right after posting was Cowper’s The Road to Corlay ff, and I’d put Davy in that category also, because AFAICT neither global warming nor nuclear winter was a concept then. (The title character was so self-centered that we don’t get a good picture of cause-and-effect, although it’s not clear there’s anyone left who understands.) I think The Sea and the Summer was the first to directly implicate people messing with the environment rather than crashing everything — from what I see in his genre work, Turner didn’t think much of people — but I last read it too long ago to be sure.

Thanks for all these additions to the list of worthy eco-fiction to read, discuss and argue about… :)

I was just recently reminded of Ursula K. LeGuin’s masterpiece “The Left Hand of Darkness,” itself a work of eco-fiction in that the Gethenians have adapted to a changed climate and hostile living conditions on Gethen. This is often what good eco-fiction (including mundane science fiction) does: prepares us through projected or imagined scenario; helping us to steel ourselves and build emotional resilience in the oncoming changes that are inevitable with global warming. Isaac Yuen wrote: “with little room for experimentation living on an unforgiving world, Gethenians have adopted a worldview that focuses less on progress, and more on presence.” We can certainly learn from their example…

I like to say that the MaddAddam trilogy killed my optimism softly with fun science. I normally avoid reading dystopias and apocalypses when their visions are too much like like our probable futures, Nope-ing away if I encounter them. But this one got me with its frequent humor, intricate and thoughtful detail,* environmental and scientific nerdiness, and vision of a better world post-apocalypse. In discussion of the final book, Atwood semi-recently advised us to “Keep hoping. It’s a chore.” But I’m unsure if she thinks we should hope that humanity will survive its own self-destructive, world-destructive actions, or hope that it won’t.

So I’d recommend it, with a trigger warning for extensive though seldom graphic inclusion of sexual violence.

*A small example: the jellyfish bracelet, a clear plastic bangle full of water and tiny jellyfish, which can be observed eating each other until the last one starves. It’s just perfect for a culture that gives freest rein to hedonistic sadism in a world where jellies are probably among the few creatures still thriving in the degraded oceans (as they’re thriving here and now, being more tolerant of acidic, oxygen-depleted water than most other sea creatures.) Another striking feature of the pre-apocalypse dystopia is its demonstration that ‘green’ technologies alone won’t save us. Solar power, vegetarian imitation meats, and technology (thermal depolymerization, I think) that turns garbage into oil have been fully embraced once their alternatives became too scarce, but without a shift in collective mindset, they merely prolong the existence of a system based on unchecked capitalist exploitation, greed, and cruelty toward nature and humans alike.

There’s a decently long list (70 titles) of solarpunk fiction and nonfiction on Goodreads. Several of the titles from this list and the comments appear there, but there’s much more as well. The Chicago Review of Books has a clifi list here as well.

Glad to see more attention on eco-fiction / clifi, although I agree with @9 that we could use more positive fiction these days.

Very nice to see The Windup Girl, which speaks lots about a possible future where the likes of Monsanto/Bayer control the food supply for most of the world. Plus oil crisis, plus global warming, plus lots of interesting ideas (best Ministry of the Environment ever). Also Dune is a must.

What about The Sheep Look Up? This novel was influencial in sparking eco-conscience/activism in Germany and other countries. The risks of emergent plagues and food chains heavily slanted towards productivity remains valid, along with the use of phytosanitary products and so on.

Finally, a side note: Bruce Sterling’s Holy Fire is not an ecology-centric novel, yet it includes, among other great items of speculation, the notion of specific strands of bacteriae that are a substitute for domestic cleaners, along with other chemical products in the world at large.

@25 Indeed, The Sea and the Summer is both a great novel and the novelization of the results of prospective research on a likely future of mankind, along the lines of “Fortress World”. Great to read, and a good word to the wise.

In George Stewart’s Earth Abides (1949), I was fascinated by his occasional descriptions of how the environment was changing with very few humans around.