One could, I imagine, construct a comfortable (but non-waterproof) bungalow out of a collection of “Best of SF” anthologies that have appeared over the decades. The names on the spines slowly evolve over time: Dozois, Hartwell, Cramer, Strahan, Horton, del Rey, Carr, Wollheim, Merril. New names appear as older established names vanish. It is a sad year that does not see at least two or three Year’s Best SF anthologies, curated by competing editors.

Still, post-Gernsbackian commercial genre SF only dates back about a century. Someone had to be the first person to assemble a Year’s Best. That someone—or rather, someones—were Everett F. Bleiler (1920–2010) & T. E. Dikty (1920–1991), who were co-editors for The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1949.

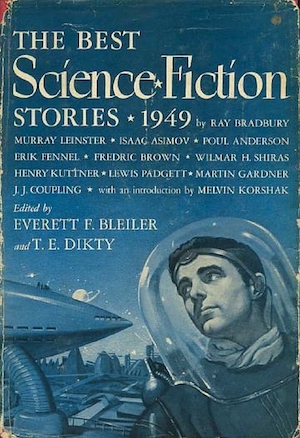

This 314-page hardcover, published by Frederick Fell, with a cover by Frank McCarthy (1924–2002) collected twelve stories from 1948. It sold for $2.95, which in today’s currency is about $30.

What did the best of 1948 look like, you wonder? I am so happy you asked.

The table of contents is dominated by men. One of the two women included, Catherine Moore, was concealed behind her husband’s byline effectively enough that an editorial comment makes it clear the editors believed the story was by Kuttner alone. Women were active in the field at the time, but as documented by Lisa Yaszek, the editors crafting SF canon were not much interested in acknowledging women. Who else, one wonders, was overlooked?

Still, one has to review the Best SF anthology one has, not the Best SF anthology you might want or wish to have at a later time. Glancing at the table of contents reveals familiar titles and names. People familiar with the field at this time will be unsurprised that stories drawn from Astounding dominate, accounting for six of the total twelve. Thrilling Wonder Stories provided a very respectable three, Blue Book and Planet Stories each supplied a single story, and the provenance of the Martin Gardner story is unclear.

I will expand on the individual stories below. For now, a short version, to wit:

As long as one has a tolerance for 1940s tropes (including an odd fondness for attributing sayings to the Chinese, a habit I had not realized was quite so widespread as this anthology suggests it was), these stories stand up reasonably well. One useful measure to which one can put a book of this vintage that cannot be applied to more recent books: of the dozen stories collected in this work, eight can reasonably be said to be still in print, in collections, anthologies, or fix-ups. Not bad for a bunch of seventy-two-year-old stories….

Introduction: Trends in Modern Science-Fiction — essay by Melvin Korshak

This is less a look at the SF of the 1940s and more a very compact, wide-ranging history of the field. Korshak sprinkles famous names throughout the text. He does not limit himself to the era of pulp magazines, preferring older roots for SF. As Judith Merril would later do in her Best SF series, Korshak rejects conventional genre boundaries, cheerfully listing literary examples of SF when it pleases him.

Preface — essay by Everett F. Bleiler and T. E. Dikty

This touches on some of the same points as Korshak’s piece, but rather than presenting a history of the field, it defends the proposition that science fiction is worth reading. The authors drape themselves in the cloak of respectability by name-checking authors with whom the general public might be familiar—Daniel Defoe, W. H. Hudson, Aldous Huxley, Edgar Allan Poe, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Jonathan Swift, and H. G. Wells—rather than names like Charles R. Tanner, Neil R. Jones, or A. E. van Vogt, of whom only SF fans would have been aware. This anthology was seemingly aimed at the general reader, not genre obsessives.

“Mars Is Heaven!” — short story by Ray Bradbury (The Martian Chronicles series)

Precisely what the third expedition to Mars expected to find is unclear, but certainly not a bucolic small town, populated by lost loved ones. That is what they find…or so it appears.

Listing all the anthologies in which this has appeared and all the adaptations would be an essay in itself. Bradbury could be terribly sentimental about old-time, small-town life. In this particular case, he isn’t.

“Ex Machina” — novelette by Henry Kuttner (as by Lewis Padgett) (Gallegher series)

Gallegher is a genius—when he is black-out drunk. Sober, his intellectual gifts elude him, as does any memory of what he did while sozzled. Usually this involves laboriously determining an enigmatic invention’s function. In this story, it means finding out whether or not he committed a double homicide.

Gallegher stories are akin to bar tales, except Gallegher generally drinks alone. The essential form rarely varies (drunk Gallegher did something and now sober Gallegher has to work out what it is) but readers clearly liked the tales, because there’s half a dozen of them. For me, the most interesting element was a passing discussion of intellectual property rights in the context of new technology, which despite being seventy-one years old is oddly applicable to current circumstances.1

“The Strange Case of John Kingman” — short story by Murray Leinster

An ambitious doctor discovers to his astonishment that an unresponsive mental patient in New Bedlam is its oldest resident, having been admitted no less than sixteen decades earlier. Precisely who or what six-fingered John Kingman is remains unclear. That the nearly catatonic entity has scientific secrets unknown to 20th-century America is clear. The effects of modern psychiatric medicine on someone who may well be alien? Well, that’s what experiments are for…

If you’ve ever wondered how Nurse Ratched would treat an insolent alien, this is the SF story for you! In the doctor’s defence, they definitely got results, although perhaps not the results they hoped for.

“Doughnut Jockey” — short story by Erik Fennel

To deliver vaccine to the Mars colony in time to prevent an epidemic, a crackerjack pilot must circumvent the remarkably contrived technical limitations of atomic rockets.

Well, they can’t all be classics. If it helps, the romance subplot is even less believable than the atomic rocket subplot.

“Thang” — short story by Martin Gardner

Humanity gets a sudden, not entirely desirable lesson about its place in the universe when Earth is abruptly consumed by a cosmic entity.

This too is no classic. This is also the first story in the anthology that seems to be out of print.

“Period Piece” — short story by John R. Pierce (as by J. J. Coupling)

Smith believed himself a man of the 20th century, transported to the 31st… until he remembered that time travel was impossible. If he is not a man from the 20th century, he must be someone else. Unfortunately for Smith, he decides to determine his true nature.

This has the distinction of being the second story in this anthology that is currently out of print.

“Knock” — short story by Fredric Brown

“The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door…”

This is an example of the alien invasion story in which the aliens are confounded by blatant lies and their unfamiliarity with terrestrial conditions. It is also an example of Brown having fun with the constraints imposed by that two-sentence set up.

“Genius” — novelette by Poul Anderson

A desperate scientist struggles to convince a slow-to-comprehend soldier that a long-running social experiment—a technologically backward planet populated exclusively by genetically superior, pacifistic geniuses—does not present a potential or actual threat to the Empire. If he fails, eight hundred million geniuses will die! But perhaps the Empire’s concern is both reasonable and far too late.

I am not sure what Bleiler and Dikty saw in this interminable tale. Technically, it is in print, but only after spending decades uncollected. For good reason….

“And the Moon Be Still as Bright” — novelette by Ray Bradbury (The Martian Chronicles series)

The Martians are dead and gone. Mars is America’s for the taking. Offended by the crass men with whom he has travelled to Mars, appalled at the prospect of Martian ruins reduced to mere tourist attractions, and afraid that Mars will become a pawn in international power politics, Spender resolves to do what any reasonable person might do in his place: become the Last Martian himself.

This story is…not entirely positive towards Bradbury’s fellow Americans, although it is more optimistic about their long-term prospects than “There Will Come Soft Rains.”2 One might get the impression from Western movies of the era that Americans wholeheartedly approved of the means by which they took their land from the indigenes. But in fact, the SF of this era is rich with stories that suggest that many authors were profoundly disquieted by the American past, although generally this showed up in stories whose moral was “genocide bad,” not “genocide avoidable” or “genocide clearly warrants reparations or at least an apology to the survivors.”

“No Connection” — short story by Isaac Asimov

Having spent his life trying to unravel the mystery of the Primate Primeval—a species of (probably) intelligent primates who vanished a million years before—an ursine scientist is intrigued to learn that intelligent primates have recently travelled across the ocean from unknown continents. The newcomers are only distant cousins of the Primate Primeval, but they share enough behavioral similarities to present a clear and present danger to the pacifistic bears.

This is another story that seems to have fallen out of print, no doubt because it is somewhat overlong for its moral.

“In Hiding” — novelette by Wilmar H. Shiras (Children of the Atom series)

At a first glance, Timothy Paul seems like a perfectly normal young teenage boy. Why then is he so socially isolated? Psychiatrist Peter Welles sets out to discover why. Sure enough, the boy is concealing a secret. Whether it is one with which Welles can assist Tim is unclear.

This is the first part of what became Children of the Atom. You may not have heard of this tale in which a well-meaning man founds a school for gifted youngsters—“gifted youngsters” being a euphemism for mutants—in a bid to avoid conflict between humans and their atomic offspring. You have almost certainly read comics and seen films that were inspired by it. Because Shiras wrote a fix-up and not an open-ended adventure series, she takes her tale in a direction altogether different from the comics that she inspired.

“Happy Ending” — novelette by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore (as by Henry Kuttner)

A robot on the lam from the future provides James Kelvin with a device that can provide all the happiness a native of the 20th century might want, in exchange for one or two minor services. One small catch: as soon as James agrees to the deal, he finds himself pursued by the android Tharn. It’s not clear what Tharn intends to do when he catches James, but James is quite certain he does not want to find out.

Kuttner and Moore employ an unusual structure here, beginning with the happy ending James covets—a million-dollar fortune—before providing the context of the happy story.

This too is out of print, although it has been frequently collected, most recently in 2010.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Speaking of the march of technology, the copyright provides a nice snapshot of IP rights circa 1949: “All rights in this book are reserved. It may not be used for dramatic-, motion-, or talking-picture picture purposes without written authorization from the holder of these rights.” I am fascinated by the distinction made between “motion pictures” and “talking pictures.”

[2]“There will Come Soft Rains”, which takes its title from the Sara Teasdale poem of the same name (https://poets.org/poem/there-will-come-soft-rains), details the efforts of the McClellan family smart-home to continue functioning after the incineration of the McClellan family, along with the rest of the human race, in a nuclear war. The family dog did manage to survive, at least for a time, but this is not as happy a development as you may expect.

I think “No Connection” was the first story I read that featured deep time (or deepish time, at least) and other species replacing H. sapiens. As such, it made a big impression.

This would have been in the early 1980s, but I was working through the school library’s SF collection, so the book of Asimov short stories could have been significantly older.

An out of print Asimov! Well, 20 years ago that would’ve been more of a surprise. Tried rereading his robot short stories a year or so ago and they haven’t aged well.

After giving it some but not much thought, I suspect the distinction between motion and talking pictures might have something to do with the distinction between cinema and television. The legal terminology for TV probably hadn’t been ironed out yet and somebody saw a potential loophole where “motion pictures” could be construed to mean only the big screen.

Here is the table of contents from Asimov and Greenberg’s The Great SF Stories: 10,

which covers the same year, but was published in 1983:

Don’t Look Now by Henry Kuttner

He Walked Around the Horses by H. Beam Piper

The Strange Case of John Kingman by Murray Leinster

That Only a Mother by Judith Merril

The Monster by A.E. Van Vogt

Dreams Are Sacred by Peter Phillips

Mars is Heaven by Ray Bradbury

Thang by Martin Gardner

Brooklyn Project by William Tenn

Ring Around the Redhead by John D. MacDonald

Period Piece by J.J. Coupling

Dormant by A.E. Van Vogt

In Hiding by Wilmar H. Shiras

Knock by Fredric Brown

A Child is Crying by John D. MacDonald

Late Night Final by Eric Frank Russell

In Hiding!! I love that story.

Darn, I’d never heard of ‘In Hiding’ in spite of being a big fan of the works following in its footsteps. Have filed it away to read shortly!

Boy — I know I read that book, checked out from Nichols Library in Naperville, IL, in like 1973 or something. But I sure don’t remember that Fennel story! Nor the Kuttner/Moore story. I’d say “In Hiding” and “Mars is Heaven!” are the two standouts for sure, and I’ve always really liked “No Connection”. The other Bradbury story is good too. I will have to try to come up with a better TOC …

It’s worth noting that Poul Anderson never reprinted “Genius” in one of his collections while he was alive. So perhaps he thought as little of it as you do! And it was something like his third published story …

In an early draft of this review, I snarked that not only did I doubt “Genius” was one of the twelve best SF stories of 1948, I doubted that it was one of the twelve best Poul Anderson stories of 1948. But then I checked ISFDB and saw that Anderson was still limiting himself to a merely human rate of writing.

“The Strange Case of John Kingman” (which I read in a different anthology a year or so ago) could almost work as a Doctor Who story told from an unusual perspective. Kingman is after all described as “aloofly amused at the impertinence of a mere human being addressing [him], who was so much greater than a mere human being that he was not even annoyed at human impertinence.”

Your synopsis for Genius reminded me of another Anderson short – Turning Point. How similar are they are?

10: Not really very similar.

Two of these stories made it into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies, “Mars is Heaven!” and “In Hiding”.

Might be worth adding a Heinlein story (“Gentlemen, be Seated” maybe) … also, Charles Harness’ “Time Trap” would be a good choice relative to many of those above. Maybe a Sturgeon (“It Wasn’t Syzygy” or “Unite and Conquer”). You could throw in a Leigh Brackett story, like “The Beast-Jewel of Mars”. I’m not a Magnus Ridolph fan, but Jack Vance published a few of those stories in 1948.

Not great pickings, really.

There’s a difficult problem with the ‘Children of the Atom’ stories/books, which is not so much a problem with this author as with the super-genius-people sub-sub-genre in general. Unless the author is much much smarter than their readers, once they get past showing their creations inventing some clever things they find it very hard to convince a reader that their fictional creations are geniuses, because it’s hard to believably portray the thoughts of someone much smarter than oneself.

If I recall correctly, Shiras wrote in the novel that the genius children all become Catholics, through logically deriving Roman Catholicism from philosophical first principles, which… no. That doesn’t really work. Not even Catholic theologians have thought that since around the time of St. Augustine, and it’s definitely not the way to convince the typical SF reader.

#2: yep, I tried to read I, Robot last year and bailed halfway through. The first story was enjoyable, the second was pretty much a thin rewrite of the first, the next was…nah.

I’ve been doing a 50-year “time-line”, reading the award winning novels and stories plus a few others. Mostly disappointing, not much of it has aged well, especially the New Wave and fantasy stuff.

The analogy I came up with is going to your grandparents’ house and they bought a new color tv…but they still have antiquated plumbing and furniture and a rotary phone on the hallway table. A little bit of what was then new tech dropped into an outdated environment.

Minor quibble: there are five Gallahger stories, not six. I presume you were misled by ISFDB, which seems to think the collection Robots Have No Tails is a story, when it is in fact the name of the collection the stories appear in. Alas, this is almost certainly by Kuttner alone. For one thing, Moore herself wrote in the introduction to the collection that she hadn’t written any of them herself (being married, I’m sure there had been some conversational influence, but no actual typing involved), and for another, the stories just don’t have any sign of her style.

Gardner got much more renowned for his Scientific American columns, and I suspect his fiction writing was collected because of general interest, not because there were any lost gems. In The No-Sided Professor, he write of “Thang”:

Martin Gardner’s “Thang” first appeared in the Fall 1948 issue of Comment.