Recently, physicists around the world were astounded to learn that painstaking testing of the visionary EmDrive revealed that the device produces no discernable thrust. By “astounded,” I mean “not astounded” and by “visionary,” I mean “almost certainly nonsensical from word one.” A cynical physicist might say the EmDrive produces thrust by violating conservation of momentum. This is unfair, because the EmDrive does not produce thrust at all.

One can understand the attraction of a reactionless drive. It comes down to the rocket equation, which presents steely-eyed rocket persons with a choice between annoyingly limited delta-v (and accordingly restricted choice of orbits), or exhaust streams energetic to a degree we don’t currently know how to manage.

The equation in question is delta-v = Vexhaust Ln(Mo/Mf) or as all the cool kids are phrasing it these days, Mo/Mf = e(delta v/Vexhaust), where delta-v is the change in velocity, Vexhaust is the velocity at which reaction mass is expelled, ln the natural logarithm, e is a constant approximately equal to 2.72, Mo is the initial total mass including propellant, and Mf is the final mass. As is intuitively clear, because e is raised to the power of delta-v/Vexhaust, as delta-v exceeds Vexhaust, Mo/Mf becomes increasingly unmanageably large.

For example, suppose we had a rocket whose Vexhaust was the computationally convenient 5 km/s. Mass ratios for various missions might look like this.

| Trip | Delta-v (km/s) | Mo/Mf |

| Low Earth Orbit to Low Mars Orbit | 5.8 | 3.2 |

| Low Earth Orbit to Low Venus Orbit | 6.9 | 4.0 |

| Low Earth Orbit to Low Ceres Orbit | 9.5 | 6.7 |

| Low Earth Orbit to Low Mercury Orbit | 13.1 | 13.7 |

| Low Earth Orbit to Low Jupiter Orbit | 24.2 | 126.5 |

The rocket equation is vexatious for SF authors for a couple of reasons: 1) It’s math. 2) It imposes enormous constraints on the sort of stories the sort of author who cares about math can tell.1 Drives that produce thrust without emitting mass are therefore very attractive. 2 Small surprise that persons with an enthusiasm for space travel and a weakness for crank science leap on each iteration of the reactionless drive as it bubbles up in the zeitgeist.

One such crank was John W. Campbell, Jr., the notorious editor of Astounding/Analog (for whom a dwindling number of awards are named). Because of his position and because authors, forever addicted to luxuries like clothing, food, and shelter, wanted to sell stories to Campbell, Campbell’s love of reactionless drives like the Dean Drive created an environment in which stories featuring such drives could flourish, at Analog and elsewhere.

Consider these five works.

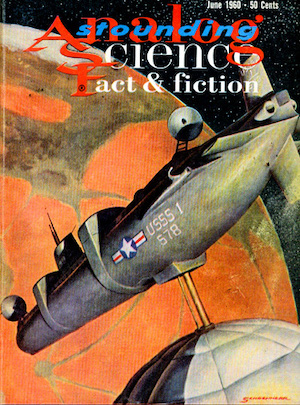

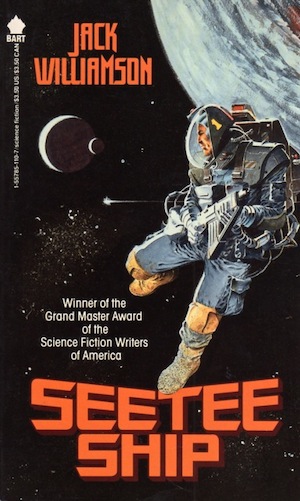

Seetee Ship by Jack Williamson (1951)

By 2190, ample sources of conventional fission fuels are running low. Not to worry! Paragravity drives make the asteroid belt easily accessible and the asteroid belt is chock-full of SeeTee or Contraterrene Matter (better known to modern readers as antimatter). Contact between SeeTee and matter produces prodigious energy. It’s the solution to humanity’s energy troubles! Except even visionaries like Rick Drake will admit the fact nobody knows how to manipulate SeeTee safely seems to make SeeTee an insurmountable opportunity. Not that Drake will let near-certain death prevent him from mastering SeeTee and freeing the Belt from the oppressive Mandate.

Why is the asteroid belt full of antimatter? The antimatter is why there’s an asteroid belt, rather than the regular world that was there until the rogue SeeTee worldlet collided with it.

The SeeTee series to which SeeTee Ship belongs is notable for featuring the first known use of the term “terraforming.”

***

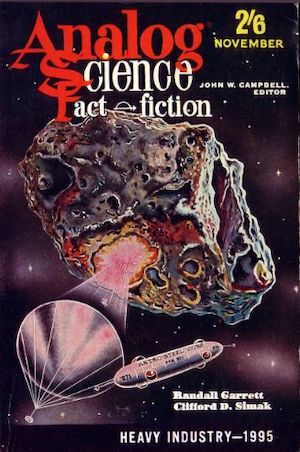

“A Spaceship Named McGuire” by Randall Garrett (1961)

The magnetogravitic drive propelling the MG-YR-7 “McGuire” spacecraft was old hat. The Yale robotic brain within it, on the other hand, is cutting-edge stuff. If the MG-YR-7 works according to plan, it will revolutionize the economics of space travel. Unfortunately, the robot brains of MG-YR-1 through 6 went bonkers and despite the minor issue that robot brains should not be able to go mad, MG-YR-7 seems to be headed down the same path. It’s up to trouble-shooter Daniel Oak to find out why.

This is notable for two details. One, the eventual explanation for what’s driving the robots nuts—a dame—is remarkably sexist by the standards of a time when women could not open a bank account without the supervision of a spouse or male relative.3 Two, this story and others like it by Garrett, are the source from which Larry Niven lifted his Belter civilization, as explained in Niven’s “How I Stole the Belt Civilization.” Examples of authors working along the same lines as Garrett and Niven are too numerous to mention, although I will sure give it a shot in a future essay.

***

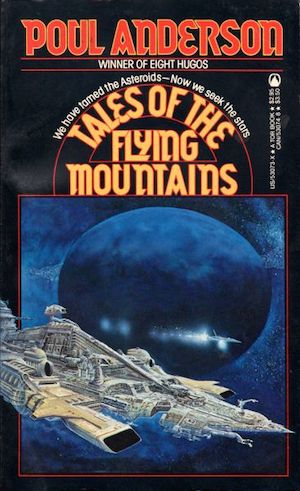

Tales of the Flying Mountains by Poul Anderson (1970)

Earth is divided and overpopulated and its space programs are faltering thanks to the realities of the rocket equation and the inability of short-sighted politicians to see the long term. Gyrogravitics could provide humanity with the means to seize space’s wealth…if only some way can be found to circumvent Earth’s stubbornly blind functionaries and so facilitate the creation of the Asteroid Republic!

This is, and I say this as something of an Anderson fan, almost the Platonic ideal of inoffensively unremarkable reactionless drive stories seemingly designed to appeal to Campbell’s various obsessions. In fact, the aspect of the collection that I remembered most clearly was how much trouble I got into at school due to the gratuitous bare breasts on the Collier Books / Macmillan cover. Dear cover artist, those are not the flying mountains to which Anderson referred!

***

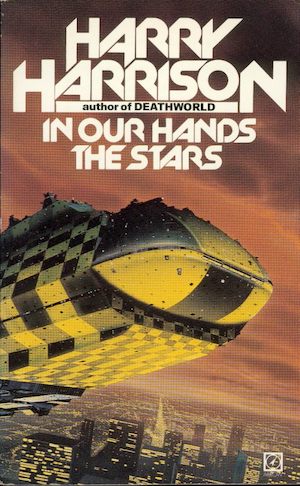

In Our Hands, the Stars by Harry Harrison (1970)

Professor Arnie Klein’s discovery leveled his Tel Aviv laboratory and presented him with a seemingly intractable problem. True, his Daleth Effect was the functional equivalent of antigravity, thus cheap space flight. At the same time, the Daleth Effect’s destructive potential was enormous. Nuclear weapons were bad enough. To whom could the Daleth Effect be entrusted who would not immediately use it for military purposes? Obviously, Denmark!

In Our Hands, the Stars is notable for two reasons. One is that rather than ignoring the weaponization potential of reactionless drives, Harrison leans into it. The other is that while Klein does not realize it, the secret of the Daleth Effect is not how it works, but that it works at all. As soon as that is revealed, there’s no hope that one nation can monopolize the physics.

***

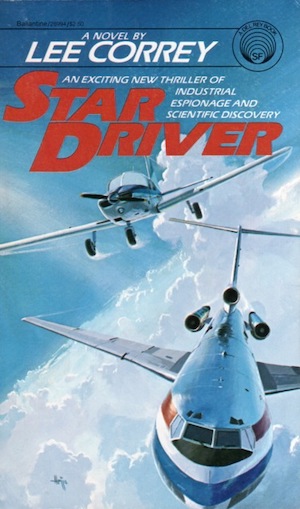

Star Driver by G. Harry Stine AKA Lee Correy (1980)

Wild Bill Osbourne’s NEMECO has a space drive. More exactly, NEMECO has something that could become a space drive. Currently, the device is mainly good for consuming research funds, testing the tolerance of lab walls for high-speed collisions, and motionlessly bursting into flames. Nevertheless, Osbourne and his team are determined to persevere in his quest to give humanity the stars—if basic engineering roadblocks and NEMECO’s bean-counters do not kneecap the project first.

Stine got roped into the whole Dean Drive thing early on and remained an enthusiast. It’s not surprising that even long after Campbell was dead and no longer a significant market for SF, Stine produced just the sort of book he could have flogged to Campbell, save for one detail. Perhaps because Stine had himself been involved in research programs, there is lots of talk early on about zooming off to Mars, but practicalities limit short-term applications to mundane demonstrations involving conventional aircraft.

***

No doubt you have your own favourite reactionless drive stories! Well, a small subset of you probably does. Perhaps a very small subset. Feel free to mention them in the comments.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF(where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]A surprisingly popular solution is to just ignore the math and have settings in which e.g. rocket powerplants produce as much power as a nuclear reactor but mass only 2.5 tons. Also, the Earth is plagued by energy shortages, chemical rockets somehow can be used to cross interstellar distances at relativistic speeds, and tramp freighters are equipped with photon drives whose output is measured in Hiroshimas/second. These freighters commonly launch from planetary surfaces that people plan on using again. Ah, the power of handwavium! Obligatory acknowledgement that Charles Sheffield managed to plausibly combine stupendous power production in space with an energy-poor Earth by having as the source of power minute black holes nobody was willing to use on Earth due to the small but non-zero risk a micro-black-hole would get free and eat the planet. Which would be bad.

[2]Yeah, yeah, solar sails and gravity exploits produce thrust without expelling mass, but they do so using external sources of momentum.

[3]“A Spaceship Named McGuire” may be astonishingly sexist, but it’s still not as bad as another story by the same author: “Queen Bee” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Queen_Bee_(Garrett_story)).

Not being a tech person I am fine with magical space drives in my fiction. I can see why the knowledgeable would differ with me on that point.

In science fiction that isn’t hard or media science fiction, going from point A to point B without a science explanation for the means is fairly standard for narrative purposes. The transporter on original TREK was “invented” because it sped up the narrative and shuttle sequences cost too dang much

SeeTee Ship had the interesting that while paragravity lets someone wrap a force bubble around an asteroid to turn it into a garden world, this isn’t exactly cheap. On the plus side, incremental expansion is possible. On the minus, neglecting to maintain infrastructure is a bad idea.

The back story is funny: the US reached the moon first and claimed it for America, graciously allowing lesser nations to claim the other planets, which were beyond practical exploitation with conventional rockets. Almost immediately after that, someone invented paragravity, and the other worlds were settled by an assortment of broad national stereotypes…

I know I’ve seen that Harrison cover before, but not on that book. Maybe one of the “TTA” books?

I read the synopsis of Queen Bee linked in the footnote, and now my brain feels dirty. Egads, that was published??

Blish’s Cities in Flight series is one of the most famous, though the spindizzy is not just a reactionless drive and effectively a free-energy device, but a faster-than-light drive and a means of holding in a flying city’s atmosphere as well. Is there anything it can’t do? Well, yes, but it can do a lot. (Petroleum prospecting is still an important business because oil is a chemical feedstock.)

A Hugo and Nebula award winning novel features a reactionless drive appearing at the climax to save the day. According to everyone I asked (and I asked three times (it just seemed the right number of times to ask)), there are no sequels to this book.

“On the plus side, incremental expansion is possibly.”

Possibly … related to ducks? Possibly deadly? Noun, sir, we need a noun!

8: Typo fixed.

Just because, I’ll mention the obvious Alderson Drive from Niven & Pournelle’s brilliant The Mote in God’s Eye, et seq. I suppose it’s not strictly speaking a reactionless drive, as it makes use of the ‘tramlines’ between points of equipotential space, so it’s more of a ‘wormhole’ type of drive. But they call it a Drive, so there you go.

5. dthurston: Yes, that was published, I read it some time in the sixties and REALLY wished I hadn’t. Given that I haven’t looked at it since then it must have made an impression, since I remembered what it was about as soon as I saw the title.

Now that I’ve looked at the synopsis for The Queen Bee, Joanna Russ’ We Who Are About To… makes much more sense.

I always admired the contragravity lifters in the Little Fuzzy books, because they’d be so wonderfully useful if only they existed. But my preteen heart was given over to the drive in John Rackham’s The Proxima Project. There is already a reactionless drive that works by shooting weights along a track, but it’s a klunky affair, only barely good enough for reaching the Moon. When the book’s quartet of geniuses/rock stars decide to go Tripping out to the nearest star system, one of them (genius, remember) figures out how to improve on that. Most authors gloss over their magic drives as quickly as possible, but Rackham (John T. Philifent) has the character explain his invention in loving detail.

@12: A lot of what Joanna Russ wrote was in reaction to previous SF. One of her short stories was incomprehensible to me until years later when I read James Blish’s Black Easter.

Another +1 for Cities in Flight and the spindizzies from me.

I feel like a close cousin to these reactionless drives are the super-efficient fusion-, fission-, or matter-conversion drives or powerplants (Asimov’s Foundation hyper-atomics or Heinlein’s torchships). The rocket equation is a big bummer 🙃

Let me add another voice to the chorus of those reading the Garrett synopsis: Ewww.

I’ve always been fond of Garrett because of the Lord Darcy stories (and Backstage Lensman) but that one is just…ugh.

I believe I read the Harrison one under the title The Daleth Effect–did they convert a submarine to a spaceship as a testbed?

Daleth effect?

LE-VI-TATE! LE-VI-TATE! YOU-WILL-BE-LE-VI-TA-TED!

4 – That looks like Chris Foss’ work. I used to have an art book with his work and that cover definitely looks like it would fit right in. I don’t recall seeing it anywhere else but I’m just one reader.

They did!

I’m currently reading a reactionless drive story, and a recent one at that, Edges by Linda Nagata.

It’s a sequel to Vast, a posthuman / space opera novel. A large part of that novel deals with an attempt to steal a zero point drive from a Berserker-like murderous alien vessel. The drive turns out to be an alien biomass that can manipulate physics in some inexplivable way, possibly extracting momentum from virtual particle pairs.

Didn’t Arthur C Clarke introduce a reactionless drive based on gravity in one of the sequels to 2001? Also, E.E. “Doc” Smith.

My favorite is pseudo-reactionless. Somehow pushes/pulls against planets or stars via handwave force/gravity beams. So momentum is conserved but you can fling spaceships around like cars. I don’t know of any clear fiction examples but some of Robert Forward’s ideas might have been in this direction.

For extra realism lightspeed still applies, so you can’t interact with the star quickly unless you’re way too close.

@21: See comment 7 for a Clarke reference.

My vote goes to The Starchild Trilogy, by Poul Anderson and I don’t remember who, or at least book one of said trilogy (I had one book with all three in it, and the previous owner had torn out the title-bearing pages, sadly).

@22 David Weber’s impeller drive might qualify. I don’t remember the exact detail of how they work. Weber (and others) also have reaction-free drives in the Starfire books, which magically cancels out inertia, too.

To be fair, there’s another kind of reactionless drive which has a more rigorous theory behind it, and it’s… also been proven to produce no thrust by the same researchers. Hmph.

On the fictional side, the humans in Larry Niven’s “Flatlander” have FTL, but are still very impressed with the Outsider STL reactionless drive. You don’t notice they’re using it until the stars start fading out from the Doppler effect.

Frederick Police, “Gateway”

@21 brucewcassidy Yes! Skylark-ian X-powered drives are the bomb! Shame X is so hard to find…

@24 IIRC, Fred Pohl and Jack Williamson.

In the collection The Best of John W. Campbell, they reprinted one of his essays, in which he said, without some sort of reactionless drive, there would probably never be a spacefaring civilization. No wonder he was so desperate to find a loophole in physics. I remember asking my father (an aerospace engineer) about the Dean Drive after reading one of Campbell’s articles, and he told me, “He’s a good editor, but he has some kooky ideas.”

I think Harry Harrison perfected this concept in Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers.

When it comes to embracing the improbability of reactionless drives, it’s hard to top Douglas Adams

@18: Yes, it looks very much like a Chris Foss. SF publishers of the 70s/80s had a habit of commissioning spaceship paintings (especially Foss ones) in bulk, buying the rights and reusing them on more than one book, so it’s quite possible that @@.-@ saw it on a different cover. It helped that the images hardly ever bore any relation to the story they enclosed, something that used to irritate me no end as a young SF fan.

(Looking at Foss’s Wikipedia entry I find now that this wasn’t entirely the publishers’ fault: Foss himself apparently had no interest in knowing anything about the story his artwork would adorn. To my astonishment I’ve also just learned that he did the famous line illustrations for The Joy Of Sex, though he didn’t use his own imagination for that commission.)

I seem to recall some probably-reactionless drives in Alastair Reynolds’ House of Suns — in particular, something called a “parametric engine”. Which was never explained,[*] but (in part as someone who learned about “parametric resonances” for part of my PhD) I liked the name for its vaguely mathematical-physics implications.

[*] The story was set several million years in the future, so violations of physics-as-we-know-it seemed somehow more plausible than “sure, we’ll invent this in the next few decades”.

I wonder if Eric Laithwaite https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Laithwaite ever read the Poul Anderson.

12: See also Poul Anderson’s “Eve Times Four”, which features a number of women hopeless cast away on an unknown world with a crewman who insists regulation number 298376 AKA the Reproduction Ace, mandates that they set up a colony with him, was also replying to Queen Bee. At the risk of spoiling a story 61 years old, it turns out they are not castaways but merely on a remote region of a settled world, and also that the horny crewman is lying through his teeth so he can have his own personal harem. It does not work out as planned.

@35: Much like (*very* much like) an episode of Futurama https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In-A-Gadda-Da-Leela

I rather like the Smoot Drive, from the Open Space comics.

The Smoot Drive

This device works by teleporting an object one “smoot” (1 atomic radius)

in a given direction. Repeating the cycle fast enough gives the illusion

of motion, but motion without inertia.

@37: that’s essentially the stutterwarp drive from Traveller 2300 CE.

zdamien @22 — I had an idea for a fictional reactionless drive a while back: an “anchor drive”. The device would drop something like a “drag line” into a parallel universe, attaching to its fundamental structure. Cheap motive power, but only for a limited set of vectors, depending on which universes one could connect to. Better-quality versions would give access to more “drag lines” at once, for combining vectors, and access to a broader variety of universes.

Of course, the original (maybe only almost?) reactionless drive was the Lensmen’s inertialess drive. No inertia, no need for any significant amount of reaction mass. Or so I seem to remember. I haven’t re-read them in many years, and my original copies were priced less than $2 each, so that’s been quite a long time.

The most common FTL trope that I recall from my early reading days was “hyperspace,” which posited a parallel universe in which the speed of light was much faster. However, it didn’t explain how a ship could reach the much-greater speed of light in any reasonable amount of time if reaction mass were required. (I mean, how much fuel, and time if we restrict ourselves to an acceleration of at most, say, 5g, would it take a conventional space craft to reach even 0.5c in our universe? Somehow, transferring to a universe where the speed of light is much greater would make the need for a reactionless drive even more acute, or so it appears to me.)

@21: Arthur C. Clarke, in (I think) 3001, posited a future in which zero-point energy powered much of the Earth. This would work like a reactionless drive without being strictly reactionless; pulling “magical” energy out of the fabric of space-time is essentially pulling mass out, and by throwing that mass overboard at the speed of light, you get a drive that does not require you to take fuel with you. I don’t remember for sure if that’s how the drive worked, however.

@@.-@, 18, 32

Yes, it’s definitely Chris Foss, it gets a two page spread in his retrospective book Hardware. Reference here since I can’t link to the book page :)

ISFDB only has it linked to an Italian printing of a Hubbard, but it could easily have been repurposed as Ridcully says, lots of his other images have been.

@40 The inertialess drive (probably) wasn’t reactionless–the speed you achieved was whatever speed caused the friction of the interstellar/intergalactic medium to equal your propulsive thrust, so they were definitely creating a propulsive thrust.

The *mechanism* for that thrust was vague–their engines had “projectors”–but I don’t think there’s anything implying a reactionless thrust. Still, can’t rule it out entirely.

@38. Might be an homage, might be parallel evolution. I would have to ask Kurt Busiek.

38: which I would not be 100 percent surprised to discover was inspired by the FTL drives in Poul Anderson’s Polesotechnic, which used “billions of quantum microjumps per second.”

Theodore Sturgeon, in his story “The World Well Lost”, postulates a “reference stasis” drive that works by shifting what you are at rest with respect to. You start out on the earth’s surface, at rest with respect to that surface; change your reference stasis to the moon, say, and now you’re moving with the same velocity as the moon — better make sure the moon is at the right point in its orbit!

Of course saying “I start moving with respect to the earth’s surface by shifting my reference stasis to the moon” is a bit like saying “I earn money by increasing my bank balance.”

@37: as almost anyone who ever spent time in the neighborhood of MIT knows, a Smoot is a little less than 6 feet, or ~~4e10 atomic radii.

@40: that’s a definition of hyperspace that I haven’t previously been familiar with; I always thought of it as a higher-dimensional shortcut (cf the explanation in A Wrinkle in Time (to Meg in the book, by Meg in a trailer scene that I don’t remember in the movie)) rather than a place with different physics.

chip137 @46 — The Lensman books made some use of parallel universes for hyperspatial travel.

The hyperspace in John E. Stith’s _Redshift Rendezvous_ involved higher-dimensional spaces which were congruent to our space. Each “level” had a progressive decrease in the speed of light, but the congruent distances scaled down even more quickly. Travel was by means of a by-your-bootstraps kind of thing where an artificial gravity source was projected outside of the vessel to attract it.

@44: I can see the book cover in your post, “Satan’s World”, in the Microsoft Edge web browser, but not in Opera.

So folks: there’s this book, it’s called “Satan’s World”. Be careful who sees you reading that. ;-)

Am I the only one who can’t see it… or the only one who can? Whoa.

@47 Lensman hyperspace is a weird example, though–things are different wrt the speed of light, but they don’t really use that fact to go faster.

They use hyperspacial tubes to go “around” our universe, but this is to avoid defenses/detection in our universe. Then there’s the other universe they can access through the tubes, where everything if moving FTL from their perspective (and matter from that universe is FTL in ours when brought here).

All that said, I know I’ve run into the idea mentioned in @40, where hyperspace is useful for traveling quickly because the speed of light is different there, but I’m not sure where, and it does raise the issue mentioned in @40. I’d say it’s far more common that hyperspace is space where the distance between two points in our universe is much shorter, which avoids that issue.

Two of my favorite reactionless space drives are:

1. The Bloater Drive from Harry Harrison’s Bill, the Galactic Hero. Whereby the spaceship itself expands interstellar distances to it’s destination, contracting back to normal size upon arrival (like a stretched and then released rubberband).

2. Murray Leinster’s Ultradrive (?). Whereby anitgravity machines are bolted to the hull of a spaceship. This bends space-time away from the ship, putting the spaceship in a bubble of Nullspace.

Dickson’s _The Space Swimmers_ might involve a reactionless drive, or it might not – I wouldn’t want to spoil the ending :)

(Well, that, and I read it 40 years ago so I’m not sure. But the I think I recall that the question of whether or not the eponymous swimmers are using a reactionless drive was a plot point.)

The Lensman’s inertialess drive was not reactionless. It expelled bright particles that occasionally had to be “baffled” to keep them from being seen. Without baffles, a ships drive was (attempting to quote from memory) ‘one of the most beautiful sights in the universe’. Movement in the hyperspace tubes is unexplained but presumably similar.

However, the Skylark’s drives, from the Skylark of Space and it’s sequels, is a proper reactionless drive. And the first one if I’m not mistaken.

The Queen Bee story would top a list of FSF stories when women (or men) are used only for breeding stock. They would have to be divided into earnestly sexist, deliberately satiric, or just plain clueless categories. The Mineshaft Gap from Dr. Strangelove comes to mind as well as A Boy And His Dog.

PamAdams @12, my housemate Supergee says that We Who Are About To…was written in response to Darkover Landfall, but I’m not sure what source he has for that. “The Queen Bee” certainly seems like enough of a blight to have attracted many countermeasures. (John Varley’s early “In the Halls of the Martian Kings” has a minor plot nod/denial of the sf topos that Garrett was working from, but it’s a small enough point that I don’t think Varley was reacting to Garrett precisely.)

There are more wormhole stories than I can list, plus variants like John Scalzi’s “Flow” in his Interdependency series — but the latest way around reaction mass may be Richard Weyand’s new Colony series, with Book 1, Quant, just published this month. It uses essential aspects of quantum mechanics to move objects instantaneously. (The details of how this ends up existing are, IMHO, quite entertaining.)

My recollection of the drive from E. E. Smith’s Lensman series is that it was explicitly a reaction drive powered, originally, by total conversion of iron to energy, later by some sort of universal cosmic energy tap (hand wavium). It achieved ftl by taking advantage of an inertialess condition (hand wavium) which allowed the ships to accelerate indefinitely, limited only by friction with the interstellar medium, without the usual temporal, spatial and mass effects. I. e., the lensman drive was not reactionless; it was a sophisticated rocket.

As to Randall Garrett, I think you’re confusing depiction with advocacy. I would have said that the opposing stereotype to the competent protagonist in A Spaceship Named McGuire was not “a dame.” It was more a bright, egocentric, irresponsible adolescent, conflated with “spoiled rich brat.” See also Unwise Child, Garrett’s novel, in which that stage in intellectual development is the central issue.

Queen Bee, also by Garrett, is not relevant to THIS article, but, since it’s being discussed, I’d point out that the appalled critics seem to be confusing depiction with advocacy. People who enjoy being sexually dominated exist and are not rare; they’re known in the BDSM community as subs. People who are willing to kill for exclusive sexual attention also exist, but are at least moderately uncommon. What to do with a murderous psychopath in a tiny community is morally difficult at best; the usual real-world solution for most societies has been to kill them. Is the solution in the story better than that? The story is not a pleasant read, and I’m surprised that Kay Tarrant let it slip by, but, obviously, it’s memorable.

I’m currently reading a novel that extensively uses what appears to be pseudoaztec terminology, supposedly based on the author’s academic study of Byzantine Imperial history, so I’ve been reviewing my own Central American history, to see if the aztecishness has any historical relevance. The Aztecs had nearly universal education, but limited women to domestic studies and obstetrics, and usually didn’t teach them to read. They also were a slaving society (in common with nearly all civilizations prior to modern European). If I wrote a story set in a society with those features, and didn’t make opposition to them my central point, would you call me sexist or slavery-affirming on that basis? Are you actually literate?

As to whether Randall Garrett was sexist, in fact, I never met the man and don’t have an opinion. His reputation was that he was hypersexual and obsessively cisgender about it, but that’s not quite the same thing.

Whoa! Was Garrett SERIOUS when he wrote “Queen Bee”? The synopsis reads like a bad J.T. Rikosh “story” written at the end of a weekend bender and intended to be submitted only to some fanzine.

He should have stuck with “Too Many Magicians”.

@21. Don’t know that “Doc” smith’s “intertialess drive” would qualify as a reacionless drive, but I had the same thought as you did.

As far as reactionless drives go, and the Dean Drive in particular, you should read Jerry Pournelle’s article on that. [https://www.jerrypournelle.com/science/dean.html]

You’re introduction of the Great Satan, John Wood Campbell into the discussion seems pointless. He didn’t invent the Dean Drive. His point in the May 1960 editorial was that IF IT WORKED, it would be wonderful, and it should be investigated.

Also, the Evil One, JWC, is not responsible for the fictional invention and use of reactionless space drives. E. E. Smith did that much earlier, in The Skylark of Space(published 1928, Amazing Stories). How, for that matter, would you categorize cavorite (H. G. Wells, 1900-1901, the Strand)?

As far as Mach or Woodward effect drives, they’ve repeatedly produced minuscule thrust for multiple investigators, the discussion is being carried on in peer-reviewed journals. It could easily turn out that they’re a dead end, but that’s not a foregone conclusion obvious to all physicists, let alone amateurs writing book reviews.

As far as non-rocket drives, the so-called solar sail is almost certainly workable, and likely capable of improvement using the fictional-staple large lasers.

As far as reaction drives go, you’ve got a point for ground to orbit lift, at the moment, but your mass at destination to mass at start ratios are seriously over-pessimistic for any other trip. Exhaust velocity of 5 km/sec is high for a non-nuclear, brute-force rocket, but it’s at least an order of magnitude too low for orbit to orbit transfers. Possibly you haven’t looked at ACTUAL, state of the art, ionic thrusters? (Deep Space 1, Dawn)

So, with regard to the Lensmen’s inertialess drive, I checked the source: Triplanetary, available via Project Gutenberg.

So, not quite reactionless; my memory was inaccurate.

@22 a drive like that doesn’t Mach any sense.

So, at least if they have their hands in the general direction of inertia, they can hide under that gigantic mystery and say that Ernst Mach and Einstein agreed with them :) then it’s just a matter of increasing the magnitude of any observed effect massively, and Bob’s your uncle!

Price/Fate of the Phoenix had some Star Trek genius creating a ship that transported itself across space. I forget the details, but a two-component ship, each with a transporter that could transport the other half of the ship, seems workable. Of course there are some issues regarding potential energy, and sufficient kinetic energy for orbit, but hey ST never worries about those things…