In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Occasionally in the annals of science fiction, there have been books that broke out of the confines of the science fiction genre and gained the attention of a wider audience and respect from mainstream critics. One of these books is Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s touching tale A Canticle for Leibowitz. It is a beautifully written story that takes a dark view of humanity, but has at its center a lot of heart and hope.

Sometimes I pick up a book that for some reason defeated me in my younger days in order to give it another try, especially when that book is critically acclaimed, and something I feel a well-rounded person should read. I gave A Canticle for Leibowitz a couple of chances in my younger days, but never got past the first 20 or 30 pages. I think that had something to do with how subdued and introspective the narrative is. Compared to another book I dearly loved back in those days, Sterling E. Lanier’s Hiero’s Journey (which I reviewed here), A Canticle for Leibowitz has little in the way of action and adventure. The protagonist of Hiero’s Journey is a post-apocalyptic warrior priest with telepathic powers and a machete who rides a giant moose into battle, and because the church had given up on the whole celibacy thing, is able to rescue and woo a beautiful young princess. Next to Hiero, A Canticle for Leibowitz’s timid and humble Brother Francis, though also a post-apocalyptic religious figure, never had a chance.

I also think my lack of understanding of the Catholic faith and monastic life also held me back from enjoying the book on my first attempts. I had an aunt who had converted to Catholicism and become a nun, spending her life working in the public works departments of a variety of Catholic hospitals. But despite the example of her life of faith, and her patient explanations of Catholic beliefs, my youthful mind could simply not wrap itself around the concept of life as a monk.

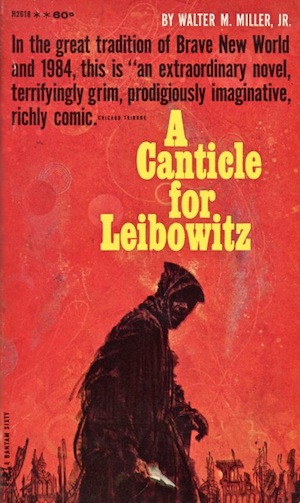

The copy I’m reviewing is a first-edition Bantam Books paperback copy published in 1961, which does not anywhere on the cover use the words “science fiction,” and touts the book as being “In the great tradition of Brave New World and 1984…” In other words, a serious book—not like those juvenile space operas the kids love. To prove how serious the subject matter is, the cover (uncredited, but reminding me of the work of artists like Paul Lehr and John Schoenherr), portrays a hooded monk on a reddish post-apocalyptic background, holding a piece of paper. Definitely not space cadet stuff.

I’m not sure the copy I read is the copy I attempted to read as a youth, or if I bought it at a used book shop sometime over the years. But it has been in my possession long enough for me to have forgotten where I acquired it. I’m pretty sure the gap between my first attempt, and my recently completed reading of the whole thing, covers about fifty years, making this a book that stayed in the To-Be-Read pile for quite a while (and in case you missed it, you can find a fun recent article and discussion on TBR piles here).

About the Author

Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1923-1996) was a rather prolific science fiction author in the middle of the 20th century. An engineer and World War II veteran, his stories were known for their technical detail, but they also often featured Judeo-Christian themes. Though he published a number of short stories, his work beyond A Canticle for Leibowitz is not as widely known, probably because at the age of 36, at the height of his career, he stopped publishing fiction. He apparently struggled with depression in his later years, and died by his own hand.

A Canticle for Leibowitz first appeared in installments from April 1955 to February 1957 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and was published as a “fix-up” novel in 1960. It won the Hugo Award for best novel in 1961. A parallel novel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman—set in the same world but taking place between some of the events of the original novel—was left unfinished at Miller’s death, completed by Terry Bisson, and published in 1997.

Like many authors whose careers started in the early 20th Century, you can find a number of Miller’s stories on Project Gutenberg.

Religion in Science Fiction

Reading Analog magazine as a teenager in the late 1960s, it seemed to me that most science fiction writers must be agnostics who expected humanity to outgrow the superstitions of religion—but I suspect that has more to do with the editorial influence of John W. Campbell than anything else. One exception to that general rule was the serial publication of the story that became the novel Dune. I suspect its inclusion in Analog had less to do with the many mythic and religious overtones of the story, and more on the fact the story centered on paranormal powers, a favorite topic of Campbell’s.

Buy the Book

A Psalm for the Wild-Built

Other magazines frequently published stories featuring religious themes, often with premises and ideas that a young and sheltered Christian like me found unsettling. One was Arthur C. Clarke’s The Star, a tale where (spoiler ahead…) scientists found that the nova that created the Christmas star had destroyed an alien civilization. And even more unsettling was the book Behold the Man by Michael Moorcock, which centered on (more spoilers ahead…) a time traveler finding that the central tenets of Christianity were wrong, and taking it upon himself to lay the foundations of the modern religion. Much more comfortable because of its engaging protagonist, and enlightening in its introduction of concepts from other religions, was Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny. I remember several stories from Robert A. Heinlein that touched on religious topics, including “If This Goes On—”, Stranger in a Strange Land, and Job: A Comedy of Justice.

And there were lots of short stories in the magazines and anthologies involving alien religions, aliens with godlike powers, humans mistaken for gods, religious allegories, and mythical subtexts. Over the years, science fiction exposed me to all sorts of religious, spiritualist, humanist, and atheist philosophies and worldviews. In the end, I’m glad for that exposure to all the different ideas, and I’ve found that instead of undermining my faith, being exposed to all the diversity of ideas has had a positive impact on me.

This summary of the topic has an admittedly personal slant to it, so for a broader view, I would refer you to an excellent article on the theme of religion in science fiction at the online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, which can be found here.

A Canticle for Leibowitz

The book opens with young Brother Francis Gerard standing a vigil in the Utah desert. He is a monk in the Order of Leibowitz, named for the founder of his abbey. In the aftermath of a nuclear war, there was a period called the Simplification in which the survivors turned on leaders and learned people, whose efforts they thought had led to the destruction. When Leibowitz was not able to find his wife in the aftermath of the war, he dedicated his life to collecting books before they could be destroyed by the Simpletons, and copying those books to preserve their knowledge. (A practice reminiscent of Irish monks in the Dark Ages, who did the same thing with works from classical antiquity.) Francis encounters an ancient wanderer, who believes himself to be the Wandering Jew—a figure from legend who taunted Christ, and is cursed to walk the Earth until Christ comes again. The wanderer leads Francis to the door of an ancient bomb shelter, where Francis finds documents apparently owned by Leibowitz himself, and remains that might be those of Leibowitz’s missing wife.

Perversely, Abbot Arkos is afraid that this trove of relics, being found just as Leibowitz is being considered for canonization, might actually delay that process as the Church takes time to verify them. Rather than being celebrated for his discovery, Francis is sent back to his vigil. But in the end, after Monsignors designated as God’s Advocate and Devil’s Advocate visit the abbey, their patron is indeed canonized. The faithful Francis, who had spent the past few years producing an illuminated copy of one of Leibowitz’s blueprints, is chosen to represent the abbey and the Order at the canonization mass in New Rome. His journey, however, is fraught with danger, and the book takes a rather jarring jump centuries into the future. We realize that the story is not about individuals, but is instead about the monastery and the Order of Leibowitz. The one continuing character is the ancient wanderer (or perhaps his successor), who appears in every era of the book. And, touchingly, in each era, Brother Francis is remembered for his devotion and piety.

In this new era, nations are beginning to expand and consolidate their territories. Learned men are no longer despised, and one of them, Thon Taddeo Pfardentrott, comes to examine the works the monks have preserved. He is shocked to find that the monks, led by the clever Brother Kornhoer, have built a primitive electrical arc light based on the writings they have preserved. It is a time of political turmoil, and while there are those who would like to turn the monastery into a fortress and military base, the monastery survives.

The narrative then jumps ahead centuries further into the future, and we find ourselves in another era, where great power competition has brought the resurgent world civilization to the brink of another atomic war, and men travel to the stars. The abbot, Zerchi, must contend with the continuing challenges of preserving the Order, government programs that conflict with the faith, and ministering to people still suffering from the radiation left after the last atomic war. Abbot Zerchi designates a team of monks, led by Brother Joshua, to take the Order’s relics and knowledge, and the teachings of the Church, to human colonies on other planets. As another atomic war begins, the book ends with a touching scene that a cynic might call a hallucination, and the faithful might call a vision or miracle, which implies that God is not finished with mankind.

The book wanders from century to century, and viewpoint to viewpoint, and the picture it paints of mankind in the future feels real and lived in. The narrative is at times almost poetical, and rich in allegory. The faith and the dedication of the Order of Leibowitz, in the face of constant reminders of the fallibility and evils of mankind, is inspiring. In the end, I found the book that had defeated me in my youth to be quite wonderful.

Final Thoughts

While there is some action and adventure in this book, it is not in the foreground. Even the individual characters fall into the background as the book follows the grand sweep of history. The tale is pessimistic about humanity in general, but hopeful that, even during our darkest moments, people will still do their duty and find courage and hope in their faiths. I found it slow as a kid, but I loved it as an adult, and would recommend it to anyone looking for a thoughtful reading experience.

And I’d like to hear from you: Have you read A Canticle for Leibowitz? If so, what did you think? And what other books with religious themes might you recommend to other readers? [And please, in your comments, be respectful of the diversity of beliefs others might hold, no matter how different they are from your own.]

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I remember reading it in the late ’70s and loving it, though was taken aback by its cynicism (as I perceived it). It’s now on my ‘re-read pile’ so I’ll be interested in what I make of it if and when I finally get round to it as I have a somewhat better knowledge of Christian theology. The idea of knowledge kept alive by monks is, of course, historical. Most of the Classical philosophers etc works survived because of early mediaeval monks copying old manuscripts.

And as a sidenote, the last episode of Babylon 5‘s fourth season has a section which is a direct homage to A Canticle.

I found the review very interesting and it reminded me of what a great book it is. The comments about religion in SF and Fantasy are useful. I would those texts that never explicitly mention religion but which are infused with a religious worldview, the Lord of the Rings being the best example.

This may be the SF book I’ve gotten the most people to read. I’ve read it countless times myself (maybe it’s time for a reread?).

I have read it although I don’t remember much I remember the time skipping and philosophical nature of it. Kind of like Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time in that way.

Much like the OP, I read it during the time when I much preferred space adventure and an optimistic view of humanity. Though I did (somehow) finish it, it was a slog. And I remember only enough about it to know that I did read it, and would never recommend it. I don’t think I can face rereading it, either, because I’m just not interested in subjecting myself to cynicism, no matter how clever or poetic.

I first read Canticle in my early teens and loved from the start. I’ve been almost afraid to go back to it, for fear it wouldn’t stand up. Although I’ve read a few of Miller’s stories recently and even those I didn’t particularly care for were extremely well-written.

In the opinion of Joe Haldeman, Miller suffered from PTSD, and the circumstantial evidence seems strong. He was a radio man and tail gunner in the air war in Italy, including being part of the bombing of Monte Cassino. You can see him trying to work through his trauma in some of his work. The abbey in Canticle is almost certainly connected to Monte Cassino. He addresses his war experiences even more directly in the short story “Wolf Pack” and seems to come to the conclusion that he’s damned for his role.

It’s a tragedy. If he’d gotten the help he obviously needed, he could have been one of the greatest SF voices of the 60s and 70s.

It’s funny. When I first read A Canticle for Liebowitz in 1970, two of the key points in the opening of the book were already obsolete. First, the Vatican Council had already made the Latin mass obsolete. Second, I had just started working as a draftsman and the new blue-line process, which produced blue lines on a white background, had finally replaced the process that produced the white on blue prints that Brother Francis found.

Didn’t make any difference to me. I loved that book from the first sentence to monk shaking the dirt of the Earth from his shoes at the end. Other books have come and gone from my list of the top 10, but this one has never fallen off it.

We read and discussed this book in my apocalyptic fiction class. I found the middle section the most illuminating (pun intended) and related strongly with Thon Taddeo. He was an atheist like myself, whose only prior exposure to religion was with fundamentalists like Marcus Apollo. Before reading this book, I’d always thought science and religion were incompatible polar opposites. But the Order of Leibowitz stood for preserving science, protecting knowledge from the Simpletons who would destroy it. When they initially closed the fallout shelter in the first section, it was to avoid a conflict of interest. And the final message in the third section was not “man was not meant to meddle” as I’d expected from a religious-themed SF book. This book blended religious and humanist themes in ways I’d never imagined. I’d never read anything like this before.

What really stuck with me was the argument between Thon Taddeo and the abbot near the end of the middle section. The abbot was quoting Genesis and the Thon was complaining about religion getting in the way of science every time– and I realized he wasn’t listening. The abbot was using scripture as an allegory and advising caution– he wasn’t spouting the expected “man must not meddle”– but that’s what the Thon heard anyway. And I realized I was a lot like Thon Taddeo, completely dismissing anything religious because it couldn’t have any merit and would only ever stand in the way of progress. And I realized I was missing the full picture.

I don’t have a copy of the book and I don’t remember exactly how their conversations went. But I remember this spark, faint in comparison with Brother Kornhoer’s light, this brief glimmer of an idea. Maybe science and religion could work together, if they both advocated for knowledge and peace over senseless violence. Because the monks in the abbey were not anti-science, they only sought to avoid repeating the mistakes that had led to the apocalypse before. It was the abuse of power and technology that was evil, not progress itself– and they understood that! Their mission was literally to save knowledge so that one day humanity could develop civilization again.

I’m sure there are a few pro-science Christians (and members of other faiths) reading this and feeling a bit insulted that it took me so long to realize something that is probably obvious to them. But hey, I grew up constantly bullied for the being the only atheist at my school, and initial impressions take some time to wear off. I doubt I’m the only student whose worldview was expanded when she encountered diverse opinions in college. Also, disclaimer for fellow atheists: I did not get sucked into religion or drink the cool-aid. I’m still very well aware that there are a few dangerous religious groups out there and that science is very much under attack. My epiphany was simply that people of science and some people of faith have more in common than we think and we can work together to stop our world getting destroyed.

Ironic that Miller, who presented what seemed to be a passionately-felt argument against suicide in Fiat Voluntas Tua, took his own life in the end. As DemetriosX says, it’s a great shame that he never got the help he needed.

I cannot see the end of the book as affirming that God was not finished. The very last scene (except for the one with the shark), where the last monk into the ship claps his sandals together — I looked that up. At some point in the Bible, Christ says that if any house refuses to accept him, for his disciples to clap their sandals together when leaving. The monk does this for the entire world, which has once again turned its back on reason and faith, and has killed itself again — I’ve always imagined for good. The few children and their guardians to getaway are a little hopeful, but it turns out that a stable breeding population is around a thousand individuals. (citation lost somewhere.)

I love the book, and have read it several times, but I see it as a harsh and bitter lesson.

@@@@@ 7 That “shake off the dust of your feet” moment was a favorite scene of mine also.

@@@@@8 I have never seen a conflict between religion and science. To me, science is how God’s creation is revealed to us I was crushed last year to hear a youngster say she didn’t like church because she believed in evolution and science, and if you believed that, you couldn’t believe in religion, too. Rigid world views on the extremes tend to obscure the fact that there is a large middle ground between faith and reason.

A Canticle for Leibowitz is a beautifully written warning.

I’m reminded that I should go back and reread this. My PB copy, stashed somewhere “safe,” is probably as old as the OP’s, since I inherited it from my mother, and my memory has the cover being the one at the top of the article.

I also find there to be a small degree of innate humor in the tale, such as Brother Francis’ successfully persuading the robbers to take his illuminated copy of the blueprint he had discovered, leaving the much more valuable but much less impressive original. Then, of course, there’s the Holy Shopping List: “Pound pastrami, can kraut, six bagels—bring home for Emma.”

I must have been in my early teens, somewhere in middle school, when I read this. I read “Alas, Babylon” and from the blurb on the back I figured this was along the same lines. Which it sort of was…. Loved the book, still have a copy of it, and have it on the Kindle. Having a copy of “A Canticle For Leibowitz” on a device known as a “Kindle” is, if not the height, certainly near it, of irony. Have reread it many times.

In the 90’s I lived near the part of Utah where the book is set. Near Scipio, where Rt 50 and Rt 91 (now I-15) meet).

The work to which I would compare Canticle isn’t Alas, Babylon but Edgar Pangborn’s Tales of a Darkening World, which is about as bleak as Canticle without the faith in god angle (there’s a church, but Pangborn is careful to detail its origins in an unflattering way). The works in the series: Davy, The Company of Glory, The Judgment of Eve, and the collection Still I Persist in Wondering.

One of my all time favorite SF novels. Holds up to multiple readings. Miller wrote a lot of great short fiction too.

I listened to a version borrowed from the library and loved it. The tripartite structure felt right in that each story was developed enough for us to care about the characters. I loved how we know so little of our idols and saints from the past, and of their actual life, and make them into symbolic figures. Like if they found some writings of mine 600 years after the fact and decided that they are of great historical importance. I thought that made the first part of the book a little comedic. The third part, of course, with its misshapen people and the doom of the approaching atomic war, is of course very depressing, as it seems to say that history is doomed to endlessly repeat.

This book has remained in my top five list of my favorite SF novels for a long time. Others have dropped off that list and new ones have entered but this is one of the perennials. Some books need to be read for historical purposes – for understanding the field – this is both an important work historically and a brilliant novel. One day I wish some publisher would bring out a collection of his complete short fiction.

My interest piqued by this very thread, A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ was duly purchased last night and has been thoroughly enjoyed since (Brother Francis has proved most agreeable company and I shall miss him), so thank you very kindly for putting me on to this most excellent work of classic fiction.

Fabulous story. Sometime in the early ’80’s, Wisconsin public radio did a radioplay of this book. You can find it still, very well done.

14 and 15; in terms of being elegiac, I always thought Canticle paired neatly with Earth Abides.

Human civilization – human history – is a thin shell on an otherwise oblivious world.

As has been said, “…all we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

Those of you in Torland, who are interested in sci-fi and religion, here’s a great resource: The Gospel According to Science Fiction: From the Twilight Zone to the Final Frontier (2007) by Gabriel McKee.