This is clearly a collaborative novel. As one commenter said, it reads as if the collaborator wrote it, and Andre Norton filled in a few blanks. Grace Allen Hogarth I am not familiar with, but her bio makes it clear that she was a prolific author in her own right, as well as a children’s book editor. This was not a case of senior writer supports junior; these two were peers.

For the most part I don’t see Norton, except for the very occasional instance of a character doing something “somehow” or without really knowing why they do it. The physicality of the characters, especially the men, and the inner lives and sexual and romantic feelings, are totally not Norton. That has to have been Hogarth.

It might have been a trunk novel for Hogarth, because although it was published in 1992, it’s set in 1951. It doesn’t just feel carefully researched. It feels as if it was written shortly after the end of World War II, at the beginning of the Korean War.

Every single detail rings true for the period. Brandy and cigarettes in a hospital room—and the nurse brings the brandy to order. Characters lighting up early, often, and wherever. Medical science not much more advanced than in the Victorian era. Food, drink, attitudes, everything, are solid 1951.

The protagonist is distinctly not the classic Norton young usually male adult. Thirty-five-year-old spinster Fredericka, rejected at twenty by a man who married someone else, has been living in New York City and working as a librarian. She hasn’t really had a life. She’s basically just been existing.

Then on impulse, out of what we might now call a midlife crisis, she answers a newspaper ad for a temporary position in rural Massachusetts. South Sutton is a tiny town, mostly consisting of a small and exclusive college. Fredericka will be taking over the management of a bookstore/lending library while its owner deals with a family crisis on the other side of the country.

Fredericka is a classic thin, upright spinster type, prim and priggish and easily irritated. She’s intensely private, she loathes children, and running the bookstore is an enormous imposition. Mostly she just wants to sleep in and work on her book on Victorian women novelists (whom I now really want to read).

Shortly after Fredericka’s arrival, a body turns up in the hammock outside the house. Fredericka is not a particularly good sleuth, though it’s clear she’s supposed to be somewhat talented in that direction. She spends far too much time bitching and moaning and ignoring the obvious, and she spends even more time mooning after the handsome Colonel from the college, who turns out to be a master spy-hunter.

The mystery is rather fun. The initial corpse is a local whom everyone loves to hate, but the method of the murder is darkly ingenious. It is fairly obvious who has to have done it, though there are plenty of diversions and a few red herrings. The second corpse is much sadder and far more cruel; Fredericka despises the victim, who is portrayed as a thoroughly unlikeable person. But others have a less jaundiced view, which makes for a nice little bit of unreliable narration, as well as an edge of pathos.

It’s clear that Hogarth was a native New Englander. Her descriptions of the landscape and the people are spot on. I went to a tiny and exclusive college in a tiny town with a wonderful bookstore housed in a Victorian mansion. I feel the setting deeply. We didn’t have a school for spies, but our Classics Department chair had been in the OSS and was a crack shot; she drove a Porsche and cultivated a succession of cantankerous cocker spaniels named after Roman empresses.

Norton’s own native landscapes were distinctly elsewhere. When she wasn’t exploring alien planets, she was focused on the American Midwest and the Southwest, and sometimes on the area around Washington, DC. South Sutton is Hogarth, and she does it well.

One thing that makes me think this novel was written in the Fifties is its gender politics. By 1992—hell, by 1972—Norton had consciously moved away from the built-in sexism of the boy’s adventure. She worked hard to develop strong female characters.

Buy the Book

A Marvellous Light

Fredericka is a woman of the novel’s time. As soon as she falls for the strong-jawed, handsome older male, she basically swoons into his arms. Although she makes frequent efforts to think for herself, she constantly seeks his approval and validation. He keeps referring to her as his “Watson,” and the way he does it makes me want to smack them both.

He is. So. Patronizing. He and the almost as sexy but very married police chief solve all the pieces of the mystery fairly handily, but they let Fredericka think she’s helping out. He constantly refers to her as a “girl,” though she’s about twenty years past that. He jollies her along, drops clues where she can’t help but trip over them, and leaps to rescue when, inevitably, she does something unspeakably stupid.

The worst part for me, especially once I did a little research and discovered that Hogarth was an editor, is the fact that so many key developments in the plot happen while Fredericka is either absent or unconscious. Norton did sometimes succumb to this, but for the most part she was a master of pacing and scene selection. A Norton novel moves at a breakneck pace, and every scene tends to follow inevitably from the one before. We are in the action from start to finish.

This collaboration does not do that. Not only does much of the action happen offstage and Fredericka is told about it afterwards, the movement is glacial and the same scene repeats over and over and over again. Fredericka wakes up in a cranky mood, usually with someone pounding on the door. She gets dressed. She makes breakfast. She and everyone else makes and drinks coffee by the gallon—including the times when she is in the hospital either because of someone else, or because she’s been coshed over the head herself.

Most of the scenes are meal scenes. Preparing them, eating them, cleaning up after them. It’s the same meal and the same menu, time after time. Sometimes, for variety, Fredericka goes to the local inn for the daily special and an Important Conversation with a Relevant Character. Once or twice, more or less randomly, she goes to church.

Cozy mysteries do make an art form of daily minutiae, and the World War II spy element adds an extra dimension. Still, I could have done with fewer breakfast scenes and less crankiness from the protagonist. What saved it for me was the strong sense of place and period. It’s not a bad example of its kind, though it seems to me to be far more Hogarth than Norton.

Next time I’ll be reading another collaboration that I’ve had my eye on for a while, one of the Time Traders continuations with Sherwood Smith, Atlantis Endgame.

Judith Tarr has written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, many of which have been published as ebooks. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

I’m wondering- where were the Norton parts in this collaboration? Did we even get a clever cat?

I enjoyed the newer Solar queen adventures- I don’t think I read the Time Traders one.

@1 The only thing I spotted were a couple of instances of characters “somehow” knowing things, or not knowing why they did or said things. It is really not a Norton novel. All I can figure is that Hogarth had plenty of platform herself, but Norton had even more, and lobbied to get this novel into print by claiming it as a collaboration. It is an amazing artifact of 1951 New England.

Your life sounds far more interesting than Fredricka’s. I was born about the time of this novel so I know the period, but I’d still be tempted to bludgeon her myself. I HATE whiny narrators and useless women. Mary Stewart and Phyllis Whitney both used this period and strong female protags to much better results.

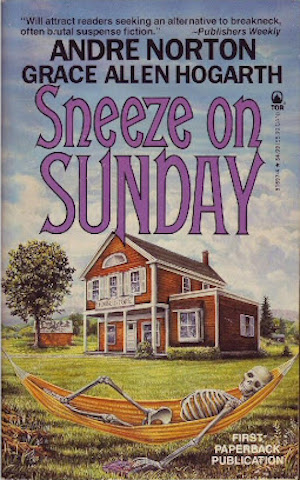

This novel was actually originally published in 1954 under the title of Murders for Sale. (Frankly, terrible title.) Not the authors’ choice, which is why it was reprinted as Sneeze on Sunday (the title they wanted) when they got the chance.

@@.-@ Ah so. That makes a great deal of sense. Thank you.

The title refers to a traditional, not to say confused and misremembered superstition or verse about sneezing. A version credited to the respectable name of “Mother Goose” is at the following link but it goes “Sneeze on a Monday” to “Sneeze on a Sunday”. And doesn’t scan.

https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/sneeze-monday

Wikipedia has a basically simpler article on subject “God bless you”.

This book jacket of “Sneeze on Sunday” is quoted here http://www.andre-norton-books.com/worlds-of-andre/novels/396-sneeze-on-sunday

“Sneeze on Sunday and safety seek, The devil will have you the rest of the week.”

That would account for going to church. Does the verse fit on other days?

The cover art pictured above was painted by Ron Walotsky and won a blue ribbon in the art show at the 1992 World Fantasy Convention.

Will you be reviewing Huon of the Horn?

@6 The whole poem gets quoted in the text. I like your explanation for why Fredericka goes to church. She certainly doesn’t seem interested in the service.

@7 Very cool. I believe I was at that convention, but I don’t remember much about the art show.

@8 Aack, another one! I’ve added it to the list. Thank you. I’ve got a bunch of Kindle editions of various things, but missed that one.