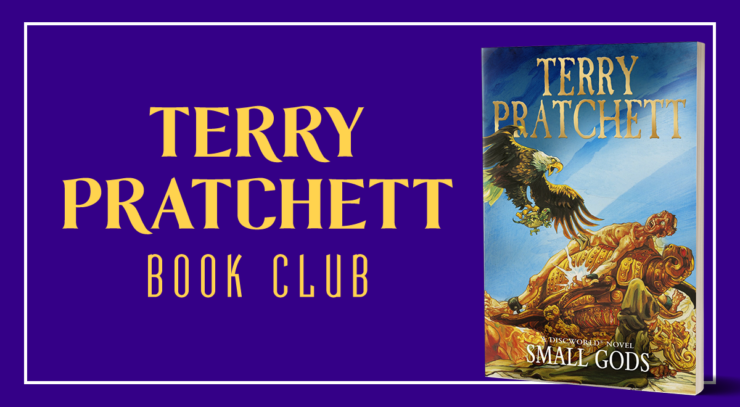

And now we turn to thoughts of a more philosophical bent on the Disc, while we begin hanging out with some Small Gods.

Summary

We are introduced to the History Monks, who keep the books of History. Lu-Tze is sent to observe Omnia; the time of the Eighth Prophet is upon them. In the Omnian Citadel, the novice Brutha is gardening when he hears a voice. He is worried about it, so he brings his concern to one of the novice masters, Brother Nhumrod, who lectures him on evil voices that will tempt him to do wrong. Brutha hears the voice again in the garden; it is a one-eyed tortoise who claims to be the Great God Om. Deacon Vorbis is the leader of the Omnian Quisition, and he tortures his (former) secretary for information on heretics, then talks to two other priests—Fri’it and Drunah—about handling Ephebe and the heathens who live there. They are supposed to parley with the Ephebans, but Vorbis wants to lead the party and bring a war to Ephebe due to what they did to “poor Brother Murdock.” In the meantime, the Turtle Movement meets in secret, a secret group that means to rescue a figure named Didactylos and stop Vorbis.

Buy the Book

Battle of the Linguist Mages

Brutha shows the tortoise to Brother Nhumrod, but he can’t hear it speak and decides it’s better for eating. Brutha saves the tortoise, but insists that he cannot be the Great God Om, and shows him the statues and paraphernalia associated with the faith while quoting scripture. Drunah and Fri’it meet to discuss Vorbis’s holy war plans and decide to go along with the wave for now. Brutha continues to question the tortoise, who doesn’t know much about all their religious books and rules, despite their religion claiming that this information came directly from Om himself. The tortoise does seem to know everything about Brutha’s life, however—which sends Brutha into a panic. Vorbis comes across Brutha holding his fingers in this ears, and asks what ails him. At the sight of him, Brutha faints. Vorbid sees the tortoise and turns it onto its back, weighing it down, while he turns back to Brutha.

Vorbis talks to Brother Nhumrod about Brutha and learns that the young man cannot read or write (it just doesn’t seem to sink in), but that he has an eidetic memory of sorts. Vorbis asks to see him once he’s recovered. Om lies on his back in the sun, thinking of what he’s done; he didn’t actually watch everything his followers did, but he was able to pull thoughts from Brutha’s head, which is how he seemed to know his history. He knows he shouldn’t have done it, and now it seems he’s going to die (gods can actually die from more than a lack of belief) because he can’t turn over and it’s getting hotter and there’s an eagle nearby—who had earlier dropped him on a compost heap, oddly enough. Almost as though something were intervening, which is impossible because he’s the divine intervention. Lu-Tze comes over and turns the tortoise upright, saving his life. Om wanders the Citadel, coming upon the things that have changed over millennia; the Quisition’s cellar where torture occurs, and the Place of Lamentation, where poor believers pray for the god’s help. Om is kicked around the floor by unknowing supplicants at prayer, and an eagle spots him for lunch.

Brutha is brought to Vorbis’s chambers and is asked about the room he entered through to give an example of his memory, which he recalls perfectly. He is told to forget this meeting and dismissed. He goes to talk to Lu-Tze before hearing the tortoise in his head again, calling for his help. Brutha accidentally walks in front of the procession of their highest priest, but he finds the tortoise and tells him about his mission for Vorbis to Ephebe. Om doesn’t much like Vorbis, and also insists on being taken with Brutha—who seems to be the only true believer in the entire Citadel. Brother Fri’it is trying to pray, but he can’t remember the last time he’s done so and meant it. He knows Vorbis is aware of his betrayal, of the fact that he appreciates foreign lands and the Turtle Movement. Just as he decides to take up his sword and go kill an exquisitor, Vorbis shows up to his chambers with two of his inquisitors in tow. Next morning, Brutha puts Om in a wicker box and the traveling group to Ephebe arrives in the courtyard. Vorbis informs one Sargeant Simony that Fri’it will not be accompanying them.

Commentary

A discussion of this book seems like it should begin with a preface or two, so that people know where I’m coming from because religion is a thorny sort of subject that people can (and do) take very personally. So here’s the deal: I’m an agnostic in a pretty literal sense, being that I do not personally believe in any god, but also contend that it is impossible for me to know what’s beyond my perception. From a cultural standpoint, I was raised by two non-practicing parents, one Jewish, the other Episcopal. Of those two heritages, I identify with the former, and would comfortably call myself a secular Jew. (The legitimacy of that vantage point varies greatly depending on who you’re talking to, but is a known stance that has existed in Judaism for at least centuries, if not longer. You can be Jewish without believing in God, and in fact, Judaism commonly requires an active questioning on faith-based subjects up to and including the existence of God.)

We should also begin this discussion with the acknowledgement that Pratchett received fan mail about this book from believers and atheists, both sides lauding him for supporting them. Which is relevant for obvious reasons, I should think.

Of course, whether this text reads as pro-or-anti religion to you, this story is very much a discussion around which aspects of religion are beneficial to humankind, and which are decidedly not. Pratchett prods at those issues in a manner even more forthright than what we’ve seen in his earlier work; the plain deadpan quality in his explanation of everything the Quisition does (it’s torture, there’s really no way around that); the acknowledgement that many people pray out of habit rather than faith; the vehement denial of any form of scientific inquiry if it’s even mildly puzzling to tenets of scripture.

There’s also room for the discussion that faith is a thing created by people, and the need to keep it flexible for that reason alone. Brutha’s quotation of the scriptures to Om leads the god to admit that he doesn’t remember insisting upon many of the commandments and laws that the Omnians count as gospel. Those interpretations (perhaps even embellishments or outright changes?) were made by human men, who in turn built this religion to suit purposes and ideas of their own. I’ve gotten flak in the past for explaining that to my mind, all religious texts are a form of mythology, but that is a large part of my reasoning there—they are written, translated, and, yes, even altered by people. We’ve got the history to prove it, which is also referenced within this novel: The mention of an Om disciple who was tall with a beard and staff and “the glow of holy horns shining out of his head” is a reference to a translation error from Hebrew about Moses coming down from Mount Sinai. (The phrase in question could be translated as “radiant” or “horns” depending on the context—oopsies, I guess?)

I feel like Pratchett sticks to a lane in this book—obviously the presence of Lu-Tze and his mobile mountains invokes Taoism, but it’s waiting there on the outskirts of this story because Omnia has a distinctly Medieval Catholic bent to it. We’re dealing with the sort of inquiries that occurred in Galileo’s time (and indeed, there is reference to him in “the Turtle Moves” phrasing), and the horrors wrought by the Spanish Inquisition. We’re also dealing with a very specific mode of zealotry that is being wielded in this case by a single person. The framework of this story is serving as a stand-in for any number of atrocities committed across history in the name of religion.

But at the center we have Brutha and Om, a true believer and his god, with their comical meetcute and their puzzled back-and-forths as they struggle to make sense of the current situation. We’ll have to wait until next week to get into the interplay of religion and philosophy that really powers this book.

Asides and little thoughts:

- There’s a point where it’s said that Brutha puts a lot of effort into running, specifically that he runs from the knees. Which probably means that he’s pretty darned fast; I took a class in Alexander Technique once, and our teacher always talked about our perception of speed, and how our instinct to tilt forward actually cost us on that front. For speed, you’re supposed to imagine that your steps begin with the movement of your knees and let that carry you forward. If you want to power walk more effectively (and reduce your chance of falling), be like Brutha and walk/run from your knees!

Pratchettisms:

When people say “It is written…” it is written here.

Time is a drug. Too much of it kills you.

And it all meant this: that there are hardly any excesses of the most crazed psychopath that cannot easily be duplicated by a normal, kindly family man who just comes in to work every day and has a job to do.

Fear is strange soil. Mainly it grows obedience like corn, which grows in rows and makes weeding easy. But sometimes it grows the potatoes of defiance, which flourish underground.

Someone up there likes me, he thought. And it’s Me.

The change in his expression was like watching a grease slick cross a pond.

Next week we read up to:

“Very big on gods. Big gods man. Always smelled of burnt hair. Naturally resistant.”

@0: suggestion

It seems that the book club is going to biweekly. I would suggest that you increase the number of pages to read each week. At the rate we’re going each book discussion will last two months.

Personally I’ve never had a problem since the Disc’s gods are so obviously not God. Not even the Creator is God, he’s Pratchett. But Small Gods is an excellent exploration of religion and it gets fan support from believers and atheists alike because it is frank about both the failings and the virtues. It doesn’t take sides so it doesn’t offend.

This was the first Discworld story I ever read. My roommate handed it to me about 20 years ago and said “start here” and since then I’ve read them all. To me this remains the single best Discworld story and is deeply rewarding on multiple rereads.

Science is not necessarily in opposition to religion. Catholic priests and lay astronomers funded by the Church made many important discoveries, including Galileo. Galileo got in trouble with the Church for drawing conclusions with theological implications that were not really justified by his observations. Also, he was challenging the scientific consensus of the day by championing Copernicus’ heliocentric theory which did not predict planetary motion as well as the Ptolemaic model. What Galileo had shown was some of the fundamental assumptions of the Ptolemaic model were wrong, but did not have a good alternative to replace it with (Copernicus’s assumption that orbits had to be circles was a great problem in aligning theory with reality). In addition, it called into question most astronomers lucrative side business as astrologers. The narrative that that was simply Religion not accepting Science is a simplistic morality play version of something much more complicated.

@2: While Discworld’s gods are not Roundworld’s gods, the religion of Om, as described in the book, has clear parallels to medieval Christianity.

@@.-@: Science is never in opposition to religion. OTOH, various religions at various times are in opposition to science. Generally this lasts until religion changes its doctrine (as it did in the case of Galileo) or declares that it is allegorical (as in the case of creation myths).

Small Gods is a brilliant book and one of my favorites. The idea that gods rise and fall based on belief can be seen in Roundworld. The Greek and Roman gods have become tourist attractions. The Norse gods have become characters in MCU movies. Other gods, like Baal, have just been forgotten. Nobody truly believes in them anymore (although they once did) and none of them have an active religion.

The book also captures how much church politics influences religion, something we see to this day in Roundworld, and that the biggest conflicts are against internal heresies and other religions.

I like Small Gods, but it always struck me as a weird outlier among the Discworld books. It’s definitely a stand-alone book, not connected to any of the established series of the setting like the Watch or the Witches. Yet, almost alone among the stand-alone books, it has none of the Wodehouse feel of most of those; it’s essentially the only major stand-alone book that isn’t in any way a romantic comedy. Which isn’t a criticism as much as a bemused observation as to why it strikes me as an odd book out.

Small Gods was the first Discworld book that I read in english, and to this day is my favourite book. I based the religions in my D&D setting on this book philolosophy.

And many years later, when I read the Eymerich novels by Evangelisti, I appreciated them much more because of Small God.

We’ve gone from a book dominated by women to a book with no major female characters and very few named women at all.

Even Brother Nhumrod would have to agree that when it came to rampant eroticism, you could do a lot better than a one-eyed tortoise. I rather think a one-eyed tortoise might be rampantly erotic — to another tortoise, as evidenced by naturalist Gerald Durrell’s account of watching a one-eyed female tortoise lay a clutch of eggs.

I enjoy all of Om’s ineffectual but creative curses. They might even rival my preferred insult: “Go kiss a cone snail, you moldering pile of old tangerines.” But despite this genuine desire to inflict painful death when frustrated, he’s still horrified to see the torture done in his name.

Brutha’s grandmother is like a more vicious version of Mrs. Cake, running the operations of the local temple.

TV Tropes says: “Although the shape of the world controversy is clearly based on the Catholic Church vs. Galileo, Omnia is more like Iran (the most obvious example of a theocracy to the modern mind). Besides its terrain and climate being reminiscent of Iran, its capital city and seat of the Cenobiarch is Kom—compare the Iranian holy city and seat of the Grand Ayatollah, Qom. Dibbler’s counterpart is also “Cut-Me-Own-Hand-Off Dhblah”, a reference to how Sharia law punishes theft by cutting hands off. Word of God confirms this: the novel was inspired by a documentary about Khomeini’s Iran.” But I haven’t located any such Word of Pratchett online.

Sneaky Pratchett referring to the aquiline face of Deacon Vorbis Aquiline = eagle-like.

It takes forty men with their feet on the ground to keep one man with his head in the air. It seems to me that this is contradicted in a Carpe Jugulum, which says, in regard to Lancre producing many magical practitioners, that only those with their feet on rock can build castles in the air.

Pratchettism:

“The number of eagles that can pick up a bull, you could count them on the fingers of one head.”

Call-backs, which are especially abundant in this book:

The joke in Pyramids about a tortoise being a well-disguised god has proven to be a whopping big plot bunny.

Looking ahead:

Enter the History Monks. Enter Omnianism. Both of them will be very important in certain later books, though not at the same time.

Pratchettisms:

“Before unbelievers get burned alive … do you sing to them first?”

“No!”

“Ah. A merciful death.”

cf ~”dressing up in tie-dyes and playing guitars at people”

The other novices make fun of him, some times. Call him the Big Dumb Ox.

An epithet also applied (at least in legend) to the young Thomas Aquinas.

…since a moment’s reflection would suggest that there are whole ranges of sins only available in company. But that was because a moment’s reflection was the biggest sin of all.

@@.-@: The Ptolemaic model predicted planetary motions only by frequent addition of epicycles — i.e., poorly if at all.

Oooh, I always think the quotes about the crops raised by fear is from Interesting Times! I’ll try and remember it from now on.

@@@@@ 5 – Baal hasn’t been forgotten, he’s bad guy in Stargate SG-1.

Emmet – Vorbis doesn’t weigh Om down, he wedges stones between his shell and the ground so that he can’t tip himself back over no matter how much he wiggles his limbs.

@5, While Discworld’s gods are not Roundworld’s gods, the religion of Om, as described in the book, has clear parallels to medieval Christianity.

More like the black legend of Medieval Catholicism. In fact the inquisition, mass burning etc. Was more a renaissance and reformation phenomenon. You know, when western civ. Started getting all enlightened. Anyway even the most devout will readily acknowledge that churches, mosques and Synagogues have big time failures.

@13: True. The book can be seen, in part, as a parallel of how the medieval church was confronted by and reacted to the outside conflict of the renaissance and the inside conflict of the reformation. But other aspects like Vorbis’ crusade or the political struggles within the church are more medieval.

I in no way meant to imply that today’s Roundworld religions are not cognizant of errors of the past or have not changed.

Brutha’s Reformation goes a lot smoother than Round World’s did. Probably because his god took an easily visible hand. On the other hand he certainly got the proliferation of sects Protestantism did. But happily their conflicts are limited to calling each other names as they argue dogma.

I’ve never understood how anybody on the Disc can be an atheist. Gods obviously, indeed painfully obviously exist. On the other hand there are some darn good arguments against any of them being worthy of worship. Except Om. Brutha gave him a real conversion experience. Om takes his job seriously now.

@15. I’ll let Constable Dorfl answer that question:

In a future book we meet an Omnian proselytizer named ‘Visit-The-Infidel-With-Explanatory-Pamphlets’. L-space explains that this is much more peaceful than the traditional `visit-the-infidel-with-swords-and thunderbolts’ approach.

Still, outside of Omnia, Om doesn’t ever seem too successful at gaining believers or worshipers.

As far as the other gods Terry sums it up in Witches Abroad and it applies to the general populace as well.

“Most witches don’t believe in gods. They know that the gods exist, of course. They even deal with them occasionally. But they don’t believe in them. They know them too well. It would be like believing in the postman.”

Pratchett covers much of the same ground, from a different angle, in <i>Hogfather</i>.

@18: I love Hogfather. But while it deals in belief it doesn’t deal much with gods. Pratchett makes a fuzzy distinction between gods (which people worship) and anthropomorphic personifications (which people don’t, there are no temples to the Hogfather).

BTW, HTML doesn’t work in this forum. To italicize something you need to select the I from the format bar above the comment box.

@19 – Bilious would like a word. He’s a bit under the weather at the moment, but maybe later.

@20: I’m sorry but worshiping at the porcelain throne doesn’t count. Although I have been known to make offerings to it.