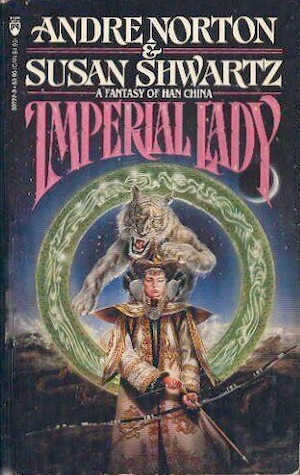

It’s been a long time since I read Imperial Lady. Long enough that I’ve forgotten the book itself, the details of plot and character. But I do remember that I read it, and I remember how much sheer gleeful fun its co-authors had in the plotting and researching and writing of it.

That fun still shows, all these years later. And so does the research, and the writing skills of both authors. Norton of course was her own and justly famous self, in 1989 as in the last days of 2021. Susan Shwartz was and is a talented writer in her own right.

It’s a good mix. The story of Lady Silver Snow in the Han Dynasty of ancient China draws extensively on what history is known of the period, as of the late 1980s. Silver Snow is the daughter of a disgraced general; she can ride and hunt and shoot a bow, which is most unlike an aristocratic lady. When summoned by the Emperor to be one of five hundred candidates for imperial concubine, she dares to hope that she may chosen to be empress, and thereby restore her father’s fortunes and her family’s honor.

That is only the beginning of her adventures. Her independence and her tendency to speak her mind gains her a powerful enemy at court, causes her to be exiled within the palace, but in the end gains her an even more powerful friend. With that friend’s help, she navigates the complexities of the imperial court, and wins a prize that to most highborn ladies would be a sentence worse than death: to be promised in marriage to the ruler of the Hsiung-Nu, the nomadic tribes that range the steppe beyond the Great Wall and engage in intermittent war and invasion with Imperial China.

Silver Snow is a terrible courtier, but she is an intrepid traveler, and she embraces the language and customs of her adopted people. Of course there is a new enemy in the tribe, an evil shaman who is also a wife of the Shan-yu, and whose brutal son intends to become Shan-yu after his elderly father dies. That, the shaman intends to happen soon.

But Silver Snow supports the other candidate for the inheritance, the son of another and now deceased wife. He is intelligent, thoughtful, and as gentle as a man of the tribe can be. He is the one sent to fetch his father’s new wife from the Chinese capital, and they forge a sometimes prickly alliance against the shaman and her son.

All the various rivalries and conflicts culminate in a breathtaking race to reach the deceased Shan-Yu and take possession of his body, which will determine who becomes Shan-Yu after him. Silver Snow is caught in the middle; she, like the corpse, will belong to the victor.

She is very much an aristocratic lady, and can seem meek and passive and prone to faint away when faced with serious opposition, but she has a core of steel. She also, most fortunately, has a magical ally of her own: a maid, rescued by her father from slavers, who has a secret. Willow is a were-fox and a shaman. She and Silver Snow love each other as sisters, and Willow is Silver Snow’s most devoted friend and strongest protector. Silver Snow, in turn, protects Willow as much as she can in a world that kills the magically endowed and sets a high value on fox skins.

The novel reads like a fairly smooth combination of its co-authors’ talents. It resonates with themes and tropes that Norton loved: the misfit protagonist who strives to restore her own and her family’s honor; the magical, highly intelligent animal companion; the headlong and complex adventure across a vividly described landscape; the villain without redemption, repeated twice as Norton sometimes liked to do, echoing plot elements in successive halves of a novel; the subtle slow burn of romance, with barely a hint of physical passion.

That last owes its development to Shwartz, but it’s carefully and respectfully done. So is the characterization in general. Shwartz gives us depth and complexity that Norton could never quite manage, but she does it with a light hand and visible respect for her coauthor.

Buy the Book

A Marvellous Light

What’s really interesting is that the prose does much the same thing. Especially at the beginning, it has the beats and the cadences of Norton’s style, but smoother, more lyrical. The flavor of Norton is there, and yet it’s a Shwartz novel, too. They fit together.

Reading the novel now, in 2021, gave me some odd and complicated feelings. The Own Voices movement and the movement in general toward diversity in both writers and their writing has changed the landscape of genre, and set a high bar for white writers writing non-white cultures. That in turn adds layers to my own reading, as a white reader reading white writers of a culture that belongs to none of us. I can say that I believe it was treated with great respect, but I would love to know how it reads to a Chinese reader.

One stylistic choice puzzles me. All the male characters have names in their own languages. All the female characters’ names are translated. I don’t know where the decision came from, or what it wanted to accomplish. In 1989 it might not have been as jarring, though it was still noticeable. In 2021, naming a character in English translation is regarded as a form of othering–erasing their proper name and giving them a label instead.

It is true that Chinese names have meaning and that meaning is very important to the person and the family. It’s helpful to know what the name means in that context. But if that’s the case, why do all the men get Chinese names and not translations? And why are the women of the Hsiung-nu also given labels instead of names?

There’s also the echo of a major icon of American pop culture from 1998 onward, Disney’s Mulan, itself based on Chinese legend and history. There are so many elements in common that I might wonder if the writers knew of this novel, though the novel is based on history that would have been well known to those same writers. The Hsiung-Nu or, as the film calls them, Huns; their leader, Shan-Yu; his raids on the Great Wall and the threat he and his people posed to the Chinese empire. (And Mulan, be it noted, does not have a translated name in any of these versions.)

It was a little eerie seeing those names and concepts in a novel written a decade before the film’s premiere. When I read the novel first, they didn’t exist. Now, we have not only the animated film but a live-action version, plus (speaking of Own Voices) a Chinese rendition of the legend.

Disney-Mulan and Silver Snow take very different paths, but their motivations are strikingly similar: to protect their father and preserve their family’s honor. The Disney Huns are dehumanized monsters; Norton and Shwartz turn them into rounded and sympathetic characters, particularly the Shan-Yu and his younger son. The latter world has more depth in general, with a somewhat more complex moral landscape, and even its villains have a certain level of excuse for what they do. The wicked eunuch covets power and wealth; the evil shaman craves those, but is also fighting for the rights of her son.

Ultimately I think Norton and Shwartz succeeded in weaving together their respective talents. Imperial Lady is a grand adventure and a loving tribute to its world and its combination of cultures.

Next up is an odd find but what looks like an interesting one: a middle-grade novel from 1975 in collaboration with Michael Gilbert: The Day of the Ness.

Judith Tarr has written historical novels s and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, many of which have been published as ebooks. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

Ooooh, “Ness.” Dare we hope it involves a certain lake monster?

I have to congratulate Susan Shwartz for making Norton better yet retaining the Norton magic. That’s a hard task.

Oooh! And it’s an eBook, too! So many of these older books are only available as paperbacks in used book strores in the USA. Those of us overseas have a hard time finding the oldies but goodies!

I’ve got the paperback somewhere.

Does anyone who has read Imperial Lady and Empire of the Eagle know whether these are really a series?

The ISFDB, Goodreads, Norton’s Wiki bibliography, as well as the AN estate authorized website (http://andre-norton-books.com/) group them together as a “Central Asia” duology but I’m highly doubtful.

I haven’t read them yet (and would read them back to back if they’re truly a series) but from what I glean the only connection is that they’re both collaborations of Norton & Schwartz, and that their setting is in Asia. But the settings seem to be quite distinct geographically (China in one case, Mesopotamia / India in the other) and maybe also in time (the starting point of Empire of the Eagle seems to be the 53 BC Battle of Carrhae while Chang’an [Xi’an] being the capital dates Imperial Lady sometime between ca. 200 BC and 23 CE).

But in my book, there needs to be more to make two novels part of a series than just being set on the same continent at perhaps the same time (or maybe centuries apart) and authored by the same authors.

I wonder if an early misunderstanding might be perpetuated by websites copying the supposed series from one another without this being so. This wouldn’t be a unique case; Tanith Lee’s two novels The Castle of Dark and Prince on a White Horse are listed as series in some places (probably because they’ve once been published in an omnibus) despite there being no connection between the two. The same is true of her two novels Sabella, or The Blood Stone and Kill the Dead which were published in the omnibus edition Sometimes, After Sunset but aren’t a series despite some sources listing them as one.

Anyway, sorry for the long rambling question.

I’d be delighted if someone in the know could clarify this question for me. :-)

Thanks!

In Robert Van Gulik’s “Judge Dee” mystery novels, set in Tang Dynasty China (7th century AD), published in the 1950’s and 1960’s, there is a similar use of Chinese-language names for male characters and English-translated names for female characters.

Since Chinese names would not be apparently “gendered” to Western readers unfamiliar with the language, I suspect this convention may have been adopted to avoid confusion over characters’ being male or female.

Oddly enough, Richard Adams did something like that in “Watership Down”, but in reverse: the male rabbits all have “English” names, but the female rabbits all have names in his made-up rabbit language.

@5, but not in all the Judge Dee books. I agree it’s strange. I just love Judge Dee.

#5/#6: Roxana’s right, the Judge Dee books are not wholly consistent about female naming conventions – but then van Gulik’s narrative choices are inconsistent in other ways, too. If I recall correctly, some details follow conventions in use during the Tang era when the main stories are set, while others follow those of the Ming period when the framing stories are set – and, again if memory serves, when many of the Chinese texts he used as sources were written.

One thing, though, from what I recall of the Judge Dee books: I believe that in those, almost all of the female characters with translated names are courtesans or women of similar class (and the translations are almost entirely names of flowers, gemstones, or the like). By contrast, most or all female characters from other professions or family backgrounds are given normal Chinese family and personal names. The single notable exception I can think of is the wrestler and teacher of wrestling “Violet Liang” from The Emperor’s Pearl, who is distinctive on two counts: one, she’s Mongolian, and thereby a foreigner as well as being of the professional entertainers’ class, and two, the surname Liang is explicitly described as a gift bestowed by Imperial decree. This is interesting and possibly illuminating, because while van Gulik may have made a number of anachronistic choices in the course of writing his novels, he was by all accounts an extremely knowledgeable scholar and wouldn’t have made the choices he did without specific reasons for doing so. (It’s also worth noting that van Gulik evidently wrote the Judge Dee books in English even though it wasn’t his native language.)

If I were going to guess, I would suggest this: I strongly suspect that at least in van Gulik, the variation in female names may reflect an actual distinction in Chinese usage, and that it might have been common practice for women in socially sensitive professions to use adopted names in order to avoid associating their familial names with their professional identities. I might also speculate that female children, particularly those still living in their parents’ households, may have been given similar personal names for use among family and friends, and also perhaps to avoid confusion in large households where there could have been multiple individuals with identical surnames *and* given names.