Recently I reviewed a venerable book I won’t identify beyond saying that it was Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Dragons of Autumn Twilight. There are many levels on which this unnamed book could legitimately be criticized, none of which mattered to the legions of readers who bought it and its many, many, many sequels. The moral here is that readers will overlook a multitude of flaws provided the book in hand manages to scratch the right itch at the right time.

At present I am immune to the charms of the unidentified book. However there are other books I read in my youth that, while flawed, are still pleasant reads. In spite of the fact that they’re a bit dated and/or lack some conventional virtues like delectable prose, compelling plotting, and vivid characterization, they still manage to hold my attention.1 Here’s a sample of five books that I continue to revisit from time to time despite their flaws or shortcomings.

Justice, Inc. by Kenneth Robeson (1939)

Accompanied by wife Alicia and daughter Alice, millionaire adventurer Richard Benson bullies his way onto a passenger plane. Fastidious Benson washes his hands in mid-flight. When he returns to his seat, Alicia and Alice are nowhere to be seen. In fact, the crew and other passengers insist Benson boarded alone. When Benson protests, he is overpowered and knocked out cold. He wakes weeks later, physically transformed by the trauma. Benson sets out to discover the fate of his wife and child, armed only with nigh-superhuman strength and reflexes, a vast fortune, and the new, trauma-induced ability to shape his paralyzed face into any face he wishes. Oh, and also many years of experience as an adventurer. Will such paltry assets suffice?

Justice, Inc shows its roots in the pulp era. It’s short. The plot moves forward energetically, without much care as to whether or not it makes sense. The prose is functional at best. The author is fond of convenient tropes like Women in Refrigerators. Alas for poor Alicia and little Alice.2

Kenneth Robeson is a pen name used by Paul Ernst for the Avenger pulp novels. Another writer, Lester Dent, who wrote the Doc Savage novels, also used the same pen name, which was owned by the publisher of both series, Street & Smith.

What makes Justice, Inc and the series of which it was a part stand out for me was that that the Avengers books were books about teamwork, whereas the Doc Savage books were all Doc, all the time. Sure, Benson has resources and is highly capable. That’s insufficient. The key to success is Benson’s ability to recognize and recruit people whose skills and resources complement his.

In this particular adventure, Benson joins forces with fellow victims of injustice Fergus “Mac” MacMurdie and Algernon Heathcote “Smitty” Smith. Mac is a skilled chemist; Smitty is a skilled mechanic and full-time bruiser. This sets the pattern for the series; the early books expand Benson’s team with other skilled, resourceful people.3 Benson depends on his team, whereas Doc Savage had hangers-on who supplied him with lavish praise and were occasionally held hostage, giving Doc a reason for a daring rescue.

Sundiver by David Brin (1980)

Much to humanity’s collective alarm, humans are not the first civilization to reach the stars. Worse yet, the billion-year-old culture (containing many non-human species) that beat us to the punch is vastly more technologically sophisticated than we are. Worst of all, the culture is rigidly hierarchical; humans must somehow fit into this society or suffer dire consequences. Having already violated some core tenets with our treatment of the Earth’s environment, humans must tread carefully lest one alien faction or another decide to exterminate the affront that is wolfling humanity. As fate has it, Sundiver—humanity’s effort to send a crewed spacecraft into the sun itself—will play a role in the delicate dance between alien and human.

Modern readers will likely find Sundiver (the novel, not the spacecraft in the novel) a bit too much of its era; not in a good way. The treatment of women in this novel makes it obvious that the novel was published closer to the midpoint of the 20th century than to today. The “uplift” which gives Brin’s series its name involves a combination of genetic manipulation and selective breeding, though the humans in the novel decry the way senior galactic patrons treat their servant races. As to the science: Brin, even at the time, must have known that cooling lasers could not work as he has them work in the book. Too bad that many readers must have accepted this as science fact.

However! The novel in hand is not the grand-scale space opera one might expect. It’s a murder mystery on an isolated space craft. It just so happens that I am, in addition to being an SF fan, am also a fan of murder mysteries set in isolated locations. Sundiver was an engaging example of the form—it is hard to get more isolated than a location within the Sun.

The novel’s structure also provided what I assume was an entirely unintended source of entertainment. Brin established the lead’s backstory convincingly enough that many readers believed that Sundiver the novel was just the latest in an ongoing series (rather than the first). We did not have ISFDB to consult back in those days. Thus, for years regulars on Usenet’s rec.arts.sf.written fielded questions about Sundiver’s non-existent predecessors. Being kindhearted people, we’d console them with the knowledge that they could at least now redirect their efforts into searching for John D. MacDonald’s classic Black Border for McGee…

The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson

The Eye in the Pyramid (1975), The Golden Apple (1975), Leviathan (1975)

Across America and the world, people find themselves facing seemingly unrelated challenges. New York Detectives Saul Goodman and Barney Muldoon have a bombing to solve. Reporter George Dorn is arrested in Mad Dog, Texas. The UK’s Agent 00005, Fission Chips, is dispatched to tiny Fernando Po to investigate Russian (or possibly Chinese) skullduggery. An American president is determined to appear resolute and strong; the nonexistent Russian (or possibly Chinese) activity in Fernando Po is just the thing to justify the use of America’s new super-weapon. In fact, all of these events are connected—evidence of a vast, planet-spanning conspiracy dating back centuries.

Inspired by various deranged letters Shea and Wilson read while working for Playboy Magazine, The Illuminatus! Trilogy is so very 1970s. If the authors were not actually on drugs when they wrote their epic celebration of paranoia, they gave a great impression that they were. The trilogy is energetically, gleefully incoherent as it tries to present a world in which all conspiracies are true.

The Phoenix Legacy by M. K. Wren

Sword of the Lamb (1981), Shadow of the Swan (1981), House of the Wolf (1981)

The Concord that rules our Solar System and the Alpha Centauri system a thousand years from now is technologically sophisticated. It also features a brutal caste system. Legions of uneducated, oppressed Bond folk serve a very small number of Elite. There’s a comparative handful of educated Fesh (professionals) who work for the Elite and help hold this creaky society together. Bonds occasionally rebel against oppression and are put down by force. Leonard Mankeen, an Elite, tried to reform the system; bloody revolt and bloodier suppression ensued. A billion people died. This disaster convinced the remaining Elite that reform—any reform—must be squelched with extreme prejudice.

But there’s hope! Brilliant but doomed Rich DeKoven Woolf and his less brilliant but far hunkier brother Alex will save the day, somehow finding a path between the Scylla of a new Dark Age and the Charybdis of handing power to a fellow revolutionary who is in fact worse than the current rulers.

Along the way, Alex will have to find some way to woo the beautiful Adrien Camine Eliseer despite the notable handicap of having faked his own death.

Younger readers will be spared the original cover art, but they will not be spared the author’s fondness for lengthy infodumps. They may also notice that while everyone is concerned about the plight of the Bonds, absolutely nobody ever suggests asking the Bonds what they think should be done. The revolution is carried out entirely by Elite and Fesh.

So, what’s to like? When I first read this, it helped that I was oblivious to the problem inherent in wanting to keep the Bonds happy enough not to rebel without being willing to give them any say in the resulting political system.4 I, uh, enjoy infodumps so that wasn’t an issue for me. I thought the two-star-system set-up was interestingly constrained. I enjoyed the fantasy that corrupt systems could be reformed. And, as my one of my editors (also a fan of the trilogy) reminds me, the three-book plot never flags; there are cliffhangers and suspense galore. Oh, and swordfights.

I also note that all three books in the trilogy came out in 1981. The cliffhangers would have otherwise been unbearable.

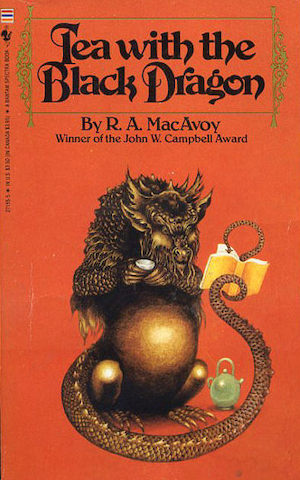

Tea with the Black Dragon by R.A. MacAvoy (1983)

Martha McNamara, former orchestral violinist turned Zen master and Celtic fiddler, arrives in San Francisco looking for her missing daughter Liz. Martha’s concern is exacerbated by the final communication Liz sent, which hinted at some crisis with which she needed help. Providentially, Martha books a room in the same hotel as the enigmatic Mayland Long. Long, believing Martha is the Zen master for whom he has been searching, assists Martha in her search for Liz. Mayland is far more than he seems—he is in fact a dragon in disguise—which is good for Martha and Liz because the people Liz is mixed up with are very bad people and Martha needs all the help she can get.

Modern readers will notice that while the plot does not quite embody the Mighty Whitey trope, in which White heroes easily master that which requires a lifetime of effort by POC, it’s close enough to touch that dubious trope with an outstretched finger. So while potential readers should be aware of that issue and the fact that the book’s portrayals will feel a bit dated, the novel also has some notable strengths. Martha is an older woman, which makes her a rarity among F&SF protagonists. The exact nature of the crime in which Liz is entangled will appeal to fans of comp.risks. The story is charming and told in sprightly fashion. Most importantly for me at the time, the paperback fit nicely in my security-guard uniform’s inside pocket without a telltale bulge and helped me stay awake through long night shifts.

***

No doubt each of you have some flawed but beloved favorites (or at least, well-liked oddities) on your shelves—and it goes without saying that your mileage may vary when it comes to the examples above. Encounters with the Suck Fairy tend to be different for everyone, and depend on a variety of factors (as does one’s level of affection for individual works encountered years and years ago). Comments are, as ever, below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and the Aurora finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is eligible to be nominated again this year, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Virtues of bad books: for me, featuring Bussard ramjets was often sufficient reason to purchase a book. The only reason “Tau Zero” is not on this list is that I’ve mentioned it before in previous Tordotcom essays.

[2]Spoilers: It turns out that both were thrown from the plane while Benson was in the restroom. Dropping a small kid out of a plane really bothered me.

[3]Benson’s team included Tuskegee graduates Josh and Rosabell Newton. In a period when African American teammates were rare in pulp and adventure and unlikely to be portrayed respectfully, Ernst made the Newtons brave, resourceful university graduates. That said, I am a bit hesitant to check to see how well their portrayal has aged.

[4]The Phoenix trilogy’s approach to the Bond issue reminds me of the “moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice” with whom Martin Luther King expressed so much frustration.

I suspect Illuminatus’ cheerful embrace of paranoia and conspiracy theory is a lot less funny to read these days.

Star Trek (with Picard) novel “Debtors’ Planet”, and for many readers that would be the problem, mostly reads to me as a decent account of diverse viewpoints, human and alien, including casting Wesley Crusher with a female romantic interest whose species basically doesn’t have males – as Wesley fortunately knows. Characters’ misunderstandings and goodwill – or the lack of it – are entertainingly drawn, including one mystifying mission specialist who is from twentieth century Earth; the reader understands him, the Enterprise crew don’t.

The exception that’s a problem is a significant character – not from Enterprise – who is betrayed and abused in the story and whose reaction doesn’t ring true to me, as it is not blind murderous rage, as the circumstances demand. Oh, well.

Two fixes did occur to me, one just now, but the first was that the betrayal and abuse have been done several times before, so to the character, it’s unpleasant – more unpleasant – but not anything new. My new second thought is that the betrayer may have taken fifteen minutes to explain calmly how and why the person was being betrayed and why they could not do anything about it, murderous rage-wise for instance. But this is my headcanon and is not in the book. One more new thought: the betrayed person is an alien too – but these aliens are quite human in their thinking. Though… one message of the book is that good people don’t have to be that. Maybe in my next re-read, I’ll have new insight.

Tea With the Black Dragon was always one of my favorites. Not only does it have a mature protagonist in Martha, but Long is described as a Black man with Asian features, one of the first Black protagonists I remember reading.

First read about Tea with the Black Dragon somewhere here on TOR and decided to try it year before last. I found it quite, quietly, enjoyable.

I liked the Avenger books, although I reject any argument that Benson is in any way superior to Doc Savage.

I’ve read many of these – I found “Tea” to be charming in spite of its issues (the sequel has issues I found harder to take, sadly). I liked the infodumps in the Phoenix Saga, too.

Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny is a book I keep going back to every couple of years. Great story but I shudder every time I read his throw away characterisation of Brahma as a predatory butch lesbian – something that sailed over my young teen head when I first read it in the early 70’s – and its very 60’s attitude to women.

The good thing about Doc Savage’s associates was that they were interesting, had fun personalities, and got all the good dialogue, since Doc himself was taciturn and almost devoid of personality. (The easier for readers to picture themselves in Doc’s action-hero shoes…)

@9AndrewMCK, speaking of Roger Zelazny, Creatures of Light and Darkness is, in my view, a flawed book shot through with genius. I can’t say it quite works as a whole, but there’s more than enough good in it that I’m grateful it exists. In fairness, Zelazny wrote is as an experiment in literary style, only publishing it at the urging of his friend Samuel Delany, as I recall.

I don’t recall “Brahma as predatory butch lesbian” in Lord of Light, but then it’s been over twenty years…

It’s been a while since I read Tea with the Black Dragon, but I thought Martha was the “master” Long needed for reasons that had nothing to do with being a zen master. Long has a huge, intellectual understanding of multiple philosophies. It’s the simple meanings of everyday living that slip past him. He doesn’t need a zen master to show him that. He needs a woman who was deserted by her husband in the 60’s, managed to raise her daughter (and do a pretty good job of it overall) while succeeding in a demanding career in an era with no daycare, and who is now middle aged, on her own, and happy with life to teach him what he hasn’t been able to see.

The Stand by Stephen King, the massive author’s edition. It falls apart in the homestretch as characters turn stupid; example: the man who saw somebody die of appendicitis choosing to move away from the place where the doctors are, instead going off into the middle of nowhere with half a dozen friends and a baby. King also fails to explain that he’s postulating a world in which the weird American Fundamentalist Christian eschatology that boils down to two monsters fighting each other at the end of the world is literally true. And he either kills off or simply fails to write believers who might have a problem with it.

But the beginning and much of the middle are enthralling writing. He is so good at getting into the heads of people who live very different lives. Even here he has issues (M-O-O-N, that spells infantilization of the neurodivergent!), but when he’s on he is on. You get caught up in the unreeling threads of all these lives, and then CHOP, here comes Captain Trips and the world begins to end.

Also a fan of Tea With The Black Dragon, although the tech side of it was already a bit dated when I read it a year or two after publication, and I recently re-read and enjoyed it. It was very rare to see strong female characters at the time, and Liz’s approach to problem-solving made a nice change from the two-fisted school of investigation.

Unfortunately not a big fan of the sequel, not sure why.

Much as I love it, ‘The Hobbit’ has the stupidest premise ever. A bunch of hard-headed dwarves hire somebody they’ve never met (with no prior experience) to steal several tons of gold right from under a dragon’s nose. Needless to say, it all goes horribly wrong – which begs the question, what was Gandalf’s gameplan? And don’t get me started on LOTR – I mean, you have a ring that can turn you invisible, but this has no real bearing on its overall significance within the story? Would YOU have been willing to gamble the whole fate of middle-earth on two hobbits? Etc, etc.

My impression of Creatures of Light and Darkness is of scraps from a filing cabinet cobbled together into a novel. The duel with the time fugues was very cool.

from memory: Sam wants to recruit Brahma (who alternates lives as male and female and doesn’t fight as female). I don’t remember the details, but Sam uses a bunch of nasty insults to get Brahma to fight.

Reading “Lord of Light” these days makes me wish for a Fanonist revolution of the oppressed Indian “colonists” against all three factions of European colonialist gods.

@17 Aonghus Fallon

…. infidel!!! …

@2 — Possibly true. I have that omnibus on my shelf and might have to find some time to reread it. However, I would guess that the Illuminatus Trilogy won’t hit the same pain point of today’s conspirators because to my recollection it never takes itself very seriously. Every conspiracy becomes embroiled in a bigger conspiracy. It’s turtles all the way down into absolutely massive absurdity which is really the heart of the fun.

Today’s “serious” conspiracy theorists just have a completely different flavor.

@2 I read the Illulminatus! trilogy when it first came out in the mid-1970’s. Looking back, I think much of it has not aged well, particularly the attitudes towards women, LGBTQ+, and the drug use.

That said, I respect the authors for doing a lot of serious research. Many of the historical works cited in the novels do exist, and was able to find a lot of them in my college’s library, and it’s impressive how they wove their story into the actual historical secret societies and subversive organizations.

I do think, however, that the prequels, “Masks of the Iluminati,” and the trilogy “The Earth Will Shake,” “The Widow’s Son” and “Nature and Nature’s God” hold up much better.

“It was almost as if sex were a thing that transcended biology; and no matter how hard he tried to suppress the memory and destroy that segment of spirit, Brahma had been born a woman and somehow was woman still. Hating this thing, he had elected to incarnate time after time as an eminently masculine man, did so, and still felt somehow inadequate, as though the mark of his true sex were branded upon his brow. It made him want to stamp his foot and grimace.”

Today it reads as transphobia, but Zelazny had Sam say “Bet every Lizzie in the world would envy you if she knew” when they speak a little later, so I think butch lesbian is what he had in mind. Nothing particularly predatory, though.

All my favorite books have flaws I’m aware of (and, no doubt, flaws I’d recognize but am not yet aware of, and generally also things other people think are flaws that I disagree about).

Maybe it’s as simple as scratching the right itch at the right time, plus fond memory. But maybe not.

Nathan Lowell’s Solar Clipper Traders Tales series (and related series) is one of my new heavy re-reads (as opposed to Doc Smith, one of my older heavy re-reads). It’s vastly too easy to make a living hauling cargo between stars in that universe, and the author’s relationship to the metric system (and to measurements in general) seems to be a bit vague (imagine the floors needed to make a hand-propelled anti-gravity lift pallet with a lift capacity in metric kilotons of any use!). My theory in this particular case is that the story is not about lift pallet capacity in any way, shape, or form–it doesn’t matter. There are no problems solved or plot points created by a lift pallet that either just can or just can’t lift some important load. Changing the rated capacity to some reasonable value would fix the error, and nothing else would need to change. Similarly, the ship being somewhere between 200,000 meters long and 528 meters long and 150 meters long may matter (I’m not sure I’m not mixing in a later ship when I add “150 meters”). Whatever, it’s the size it is, the absurd value can be viewed as a typo easily enough. No plot points are created or resolved by precise details of physical size. Possibly my mind has inflated the extreme cases, but there are actual absurdities in the text, and they don’t matter.

Glory Road by Heinlein—one of my favorite books especially since it gives us the hero’s quest and lets us know what happens AFTER the hero gets to marry the princess. Except on reread the part where Oscar shouts at Star and she responds meekly “yes, m’lord husband.” While she may have been playing a part to build his ego it still doesn’t hold p well.

@25, I don’t remember the exact circumstance it as a woman I advise men to watch out when a woman suddenly turns meek. She may have decided you’re right but most likely you’re about to get a dose of relationship jujitsu.

It stands to reason that nobody quietly says “fine” except to indicate that things are in fact fine. That’s just basic logic.

@17: This is where Jackson’s movies actually improve on the book. You get to see how Gandalf is suddenly called away by the press of other events, and also get a lot of examples of how he dislikes explaining himself.

1. All books are flawed, just as all people are.

2. As it happens, I’m rereading the Phoenix Legacy series right now. One of my favorite romantic SFF series – the Mary Stewart of science fiction.

Nothing you say about Illuminatus! sounds flawed. ;)

I wonder in forty or fifty years how many of today’s acclaimed and award winning science fiction tales will be considered flawed by some future standard?

My favorite Roger Zelazny is Doorways in the Sand, a largely forgotten work but Zelazny at his charming best. It’s a bit dated but the themes, the humor, the humanity still entertain.

I confess that of the original handful I’ve only read Sundiver and Tea with the Black Dragon – which I enjoyed (the sequel less so) and I don’t remember noting any major flaws. Mind you it’s been some decades since I last read either and it may be that I’m just an acritical reader (as well as being younger).

I seem to have read many of the books/authors cited in these Comments, again with little recognition of flaws mentioned. Lord of Light is a particular favourite, as is Glory Road (one of the few Heinlein books I can stomach these days and I have just picked up another copy… ); The Stand (original ‘short’ published version) is the only King book I’ve actually read and I was underwhelmed and the EE ‘Doc’ Smith books, which I eagerly absorbed as a callow youth, have not stood the test of time for me.

The Hobbit is an oddity: I love The Lord of the Rings and have done since discovering it in the early 60s (just bought the Tolkien-illustrated ebook to add to the collection) and yes, there are flaws therein. It took me several years to realise that I’d actually read The Hobbit previously and somehow failed to connect the two… I’m less keen on it (a bit twee? Not sure – and I have reread recently several early Alan Garner books that might also be classed as ‘young’ reader books, as also Lewis’s Narnia books so it’s not just that).

Dragon lance is venerable???

The long version makes a solid case for the utility of editors.

I reread Carrie five years ago for the first time in 40 years and was astonished how much of the book is about how the mass media deals with catastrophic events. It’s clear from the beginning that the high school dance did not go entirely well, but the version of events the public hears is not the same as what actually happens.

34: Dragonlance is almost 40 years old. It is to modern readers as old as A Logic Named Joe was when DL came out.

FINALLY, SOMEONE ELSE WHO HAS BEEF WITH THE DRAGONLANCE CHRONICLES

raistlin was my first encounter with the Type Of Guy(TM) who would, circa ~2015 to present, self-identify as an incel, and while middle school me didn’t have the vocabulary to articulate it at the time, BOY OH BOY did i know i did not care at all for THAT. it’s a genuine shame that so many of those books had such cool cover art, it’s like the literary version of a movie/tv show _desperately_ undeserving of the fantastic soundtrack it got.

goddamn raisin bastard, out here being so insufferable not even the usually sure-thing man-with-a-plan & grounded-support-guy dynamic he (nominally) had with his brother could save him. blegh.

I’ve read most of these but gave up on the Illuminati trilogy. The authors came off to me as thinking they were very, very clever. I didn’t.

Lester Dent was a much better writer than Paul Ernst. And Doc’s crew played more of a role than you give them credit for. That said, I do like the Avenger books. And to his credit, Ernst included a black man and woman on the team which was novel for the day.

The thing that bugs me about it whenever I reread it is the treatment of black men and LGBTQ men (not that there’s much), and the apparent near-complete lack of Hispanics in East Texas. As I read it, I start mentally assigning varied ethnicities to characters as they show up, just to make it seem like the superflu wasn’t even more fatal to nonwhites.

But it’s still my favorite of his novels. It’s just dated.

I’m in the Tea With the Black Dragon fan group. I have found it to be a delightful reread, not sure how many times I’ve done so.

My flawed reread choice is Number of the Beast by Robert Heinlein.

NancyLebovitz (18): you’re thinking of the god/dess of thieves, whose name eludes me but is not Brahma.

I’ve been rereading some Tarzan novels and hoo boy, talk about flawed?

(Which also raises the distinction between: Flawed book that I will still read because I can enjoy it in some nostalgic fashion vs. flawed book that I would ever recommend anybody else read, at least without some lengthy discussions; and right now, Tarzan is falling very much into the former category, not the latter.)

#40: Helba.

I noticed no one has mentioned A.E. “Doc” Smith’s “Lensman” series or his “Skylark” series. Horribly flawed, sexist, and UNBELIEVABLY “perfect” heroes (and a few heroines; I’ll give him that). But, damn; they were fun to read!

If you choose to read Illuminatus!, follow the good advise that I was given: write down the name of every character the first time you encounter them. Note the page number, and if you are feeling fiesty, a one-sentence description what they are doing. You will be grateful to have the reference during the second encounter of each character, no fewer than 400 pages later.

@36 – Raistlin wasn’t exactly the hero of those books, you know. He’s literally evil, indeed that’s right there front and centre in the story – Caramon and the others trying (and failing) to influence him to the light side. His robes literally and symbolically turn black as he makes a conscious choice to be evil.

You’re really not supposed to “care for it”! (Though I grant you, some readers do love Raistlin).

Not only that, but I don’t really see him as an incel. His bitterness and frustration was far more about his physical frailty (especially contrasted with Caramon’s strength and health). I read it as a nerd vs jock thing. Sex barely came into it as I remember – though it’s been many years since I read them, so don’t quote me on that last.

43: When I reread Gray Lensman seven years ago, I was astonished to discover a subplot I’d totally forgot about in the 35 years since I previously read it.

One plot element that had slipped right out of memory is Kinnison’s love life. Specifically, the time and effort Port Admiral Haynes and Surgeon-Marshal Lacy invest in shipping Kinnison with his One True Love Clarissa MacDougall.

@43 – I only ever read the end part of a Doc Smith series in a loose copy of “Worlds of If” that I picked up when I was about 12. Didn’t mind it then. Many years later, as an adult, I purchased both the Lensmen series and the Skylark series and few others, wanting to see why people like Heinlein and a few others of his era thought so much of him. Worst waste of money ever. Totally unbelievably crap science, even for the day. Appalling writing, even for science fiction of the day. The sexist stereotypes and perfect heroes are the least of the worries. Calling the characters cardboard cutouts would be an insult to cardboard. I was a fairly intelligent 12-year-old in the mid/late 60s. I had grown out of this sort of nonsense within few years or so, thanks to much better writers. The Lensmen series was published between 1937 & 1948. At the same time, we got Out of the Silent Planet (1938, with the rest of the series finishing in 1945); If This Goes On (short story, 1940); Nightfall (Short story, 1941); Simak’s City series (starting 1944), as well as many other significant authors (Sturgeon, Moore, Leinster, van Vogt, to name a few. And within the next 5 years, you get 1984; I Robot, Martian Chronicles, Day of the Triffids, The demolished Man, Fahrenheit 451, Childhoods End, The Space Merchants, Bring the Jubilee, Mission of Gravity and so many more.

Smith was just a hack. There are flaws with many stories by many writers which are worth rereading. None of “Doc” Smith’s works fit that category, IMO. They are virtually unreadable anymore – the kids know more science these days and have grown up reading better written works. Those of us who may have grown up with them have matured.

Just a reminder to keep the tone of the discussion civil and constructive, and try to focus criticism on the work/writing, rather than laying into individual authors or resorting to name-calling. Thanks!

@45: Yeah. Raistlin is depicred as uninterested in sex. In one of the books, we’re told that he once tried sex with one of Caramon’s girlfriends and found the experience boring. So I don’t think he would consider himself to be tragically and involuntarily celibate.

@43, @47 Another aspect of the Lensman series that has not aged well is the strong undercurrent of eugenics running through it, with the idea of the Arisians “selectively breeding” different peoples (including Earth people) to the kind of “superior race” that could wield the lens.

To be fair, though, at the time that Smith and a lot of other writers of that era were coming of age, eugenics was still considered a legitimate branch of the biological sciences, and was even studied extensively at major universities (Yale was a major center of eugenics studies then). This probably helps explain why a lot of SF from this period so often features “superior” people arising from a general population. It took the rise of Hitler and WWII to finally delegitimize eugenics, which had a further effect on how such stories might be written.

Heinlein was also “guilty” this in his rather bleak novella “Gulf,” in which a group of self-defined “genius” people agree to band together and breed a “homo superior” race that would secretly and benevolently keep the “Common Man” safe and in line. He must have felt some regrets for writing this, as time went on, for in his much later novel, “Friday,” set in the same fictional timeline, he has characters disavow the “supermen” and their intention.

The problem with this model is that formal eugenics programs continued into the 1980s and it is easy enough to spot applied eugenics even today.

The Arisian eugenics program to breed someone able to use their lens gives me an amusing idea for a story about an unnamed oligarch who sets out to breed better drivers able to use the poorly designed UI in their electric cars.

I love Zelanzy’s Amber series but I admit to being bothered by the lack of non-western people and features in the City that’s supposed to be the basis of all reality. And I’m not at all sensitive to such things.

@17 / Aonghus Fallon: “And don’t get me started on LOTR – I mean, you have a ring that can turn you invisible, but this has no real bearing on its overall significance within the story?”

You know, I’ve been a huge Tolkien fan for 30 years now, and that’s a very valid point that never occurred to me before. Of course, the problem arose from Tolkien having to find a way to tie The Hobbit into his larger mythology — in the First Edition of The Hobbit, the Ring was simply a “magic ring”, a fun and useful plot device.

@47: I’ve always thought a hack was someone who churned out crap to make a living; Smith had a good job, and AFAIK wrote for fun. (He certainly didn’t write for prestige; see the discussion of the award named after him.) It’s true that he did not develop much from his beginnings, but there were still readers in the 1950’s (or later) whose tastes were still in the 1920’s. I’m not a fan of his work either, but ISTM you’re over-judging.

I like Doorways in the Sand very much as well, and reread it every few years. I am also extremely fond of Road Marks and slightly less of This Immortal. I tried the Amber ones, but reacted very unfavorably. Ah, well. I’m a big fan of Tea with the Black Dragon and was also underwhelmed by the sequel.

#53: I didn’t quite have that issue, and I like renaissance Italy, but Amber didn’t seem all that wonderful, considering that it’s the center of the universes. The sky is a darker blue? That’s it? The Courts of Chaos weren’t all that chaotic, either.

Mezentia isn’t obviously better than life in The Worm Ouroboros, either.

I’m one of the few people who liked Nine Princes in Amber, but thought the series was going downhill after that. Most people seem to like the first five and not the second five. And I knew someone who liked all ten a *lot* and was invested in the metaphysics for the whole series.

#57: I think “hack” is just an insult applied to prolific writers. If you don’t like the stories, be specific about what you don’t like about them.

I’m fond of Smith– a lot of enthusiasm, intelligence, and inventiveness. I appreciate things like that detection is as important as force.

I really liked Tea with the Black Dragon when it came out, but haven’t reread it. What I remember most was it was SF/Fantasy, but set in a very contemporary world. So small computers are part of it, I think they even visit a computer store (when they were small and just sold computers). And read computer magazines, I think Dr. Dobbs is mentioned.

Now that’s as dated as the soda fiuntain in Have Spacesuit, Will Travel.

Three years later, there was a sequel, Twisting the Rope, but I remember no details.

RE: Smith

I must speak in defense. While Lensman is flawed by its theme of eugenics, it is one of the first SF stories where we see the good guys start to think instead of punching. There are several times where the hero is getting ready to go full blasters and the voice of Mentor breaks in saying “this is yet another example of sloppy thinking. Think, youth, THINK.” This broke the ground for Foundation where the good guys beat the big militaristic bad buys by sitting still and letting the forces of history work in their favor. Lensman broke the ground for heroes who win by being smart instead of being stronger. Yes, flawed, but I will always cheer for this part of it.

Plus Nadrek!.

In EE Smith, the good guys win by being stronger, but also more benevolent– they’re better at deservedly making coalitions than the bad guys. I don’t know where this fits in the history of the field.

@61 It was transition. Before Smith space opera was all “I got bigger weapons than last chapter so there!” and after Smith it was more like “yeah we’ve got weapons but we also have diplomacy and the forces of psychohistory and a lot more than just bigger and bigger weapons.”