“There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” The good folks at Tor.com love SF writers (well … duh) but they also understand that it is our job to not exactly tell the truth. As I am a distinctly unreliable narrator, I have been sternly warned that if I am claiming to write facts for you lot, I had better have the citations to back them up. Ugh. I write science fiction for a reason.

Well, fine then. That quote is from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5. Hamlet wasn’t wrong. There are things out there far stranger than we can possibly imagine. Like what, you might ask. To which my answer is this: I have no freakin’ clue because I can’t possibly imagine it.

Which is where science—“philosophy” in Shakespeare’s day—comes in. Science is always discovering new things, things that no one had thought of before. Sometimes they turn out not to be true, but they invariably have science fiction writers, with our limited human imaginations, scrambling to catch up. From the early days of SF, writers of science fiction have relied on finders of science fact to launch our stories into entirely new directions. You could do this exercise for pretty much any branch of science, but let’s stick with my own personal favorite, outer space.

Back in 1877, the Italian astronomer, Giovanni Schiaparelli, using telescopes that were the best available at the time, observed what, to him, looked like dense, linear formations on the planet Mars that he identified as “canali,” or “channels.”1 “Canali” however got mistranslated as “canals” and, in 1895, Percival Lowell, the influential American astronomer, published a book arguing that there were canals on Mars and that a struggling Martian civilization was using them to move water from the poles to the rest of that desert world2. Science fiction followed Lowell’s lead. In 1898, H.G. Wells produced War of the Worlds, in which envious, highly advanced Martians launch an invasion of Earth from their dying planet3. Similar themes can be found in Edgar Rice Burrough’s 1912 pulp classic, A Princess of Mars, which was also the basis for the (in my view) deeply under-appreciated 2012 movie, John Carter. Despite scientists’ protestations to the contrary, SF stories about Martian civilization weren’t fully laid to rest until the Mariner 4 flyby of Mars in 19654.

War of the Worlds was exceedingly vague, of course, about how the Martians reached Earth. In the novel, human telescopes detect huge explosions on the Martian surface and then, several months later, the Martians arrive. The implication at the time was that they must have been launched from incredibly large guns á la Jules Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon. But the problem with shooting living things into space using a gun is that, if you do the math, the acceleration required would turn everyone into strawberry jam5. Rockets, first suggested by the Russian genius, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky6, in 1903, are a better way to go.

Despite the objections of the New York Times, opining in 1920 that rockets couldn’t work in space because there would be no air to push against (I can’t even), SF eventually picked up the baton7. In the 1933 novel When Worlds Collide by Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie, humans escape from a doomed planet Earth using “atomic rockets.” By the time we get to Robert Heinlein’s Rocket Ship Galileo in 1947 rockets are pretty much ubiquitous in science fiction and remain so to this day (the propulsion used in my own novel, Braking Day, is also some kind of super-powerful rocket, although I haven’t the faintest idea how it works. Matter-anti-matter? Space pixies?).

Rockets in the real world(s) have also been ubiquitous in the exploration of our solar system. In the 1970s they hurled Voyagers One and Two into their grand tour of the outer planets, including Jupiter and its moons8. Not long thereafter, having examined the photographs, scientists started suggesting that Jupiter’s moon, Europa, might harbor a vast underground ocean, something no one in SF had previously imagined9.

But, yet again, when science finds something new, SF scurries along after to make use of it. Europa’s underground ocean features in Arthur C. Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two, written in 1982 and, more centrally, in the low budget but geekily entertaining movie, Europa Report, released in 2013. And now, to bring matters more or less up to date, we have the discovery of seven Earth-sized planets orbiting the red dwarf designated 2MASS J23062928–0502285 in the constellation of Aquarius. The address is a bit of a mouthful, I know, but, fortunately for us, we can now refer to it as TRAPPIST-110 .

Buy the Book

Braking Day

In 2016 and 2017, observations with numerous space- and ground-based telescopes, including the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) telescope at La Silla Observatory, Chile, led to the discovery of initially three, then seven terrestrial planets around the star. The planets are all incredibly close in—if you stood on the night side of TRAPPIST-1b, the innermost world, the other six planets would be clearly visible, and the nearest, 1c, would appear larger than our moon. Even more exciting, of the seven planets in orbit, three are believed to lie within the star’s so-called habitable zone, where the temperature is conducive to the existence of liquid water. Imagine, three habitable worlds whizzing by each other at close quarters every few days!

Interestingly, though, so far as I’m aware, no one did imagine such a thing. Locked into our single solar system, with its single habitable world and the outer marches patrolled by gas and ice giants, how could we? I’ve read SF books with reference to systems with, say, two human-habitable worlds. Sometimes even in our own solar system. In Paul Capon’s The Other Side of the Sun, for instance, first published in 1950, there is a “counter-Earth” sharing the same orbit as our own planet but forever hidden on—wait for it—the other side of the sun. But three or four such planets? Around a red dwarf? Never! The solar systems science has discovered so far look nothing like our own, and TRAPPIST-1 is no exception11 . But, once science opens the door, science fiction barges its way in without so much a by-your-leave.

Enter Fortuna, by Kristyn Merbeth, published in 2018, and the first in a trilogy dealing with smuggling, crime, and alien artifacts in a system containing no less than five human-inhabited planets, none of which seems prepared to get on with any of the others. I know fiction thrives on conflict, but five planets at daggers drawn is next level. And all triggered, as Merbeth herself explains at the end of the book, by the TRAPPIST-1 discovery.

Science, which doesn’t rely on the human imagination to unearth weird sh— er, stuff, is truly stranger than science fiction. And long may that continue. I can’t wait to find out what comes next. And to read the stories that come out of it.

Of Scottish and Nigerian descent, Adam Oyebanji is an escapee from Birmingham University and Harvard Law School. He currently lives in Pittsburgh, PA with a wife, child, and two embarrassingly large dogs. When he’s not out among the stars, Adam works in the field of counter-terrorist financing: helping banks choke off the money supply that builds weapons of mass destruction, narcotics empires, and human trafficking networks. Braking Day is his first novel.

[1]https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/postsecondary/features/F_Canali_and_First_Martians.html

[2]https://archive.ph/20120912195828/http:/www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/Cosmic-Errors.html?c=y&page=2

[3]https://www.amazon.com/War-Worlds-H-G-Wells/dp/1505260795

[4]https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/mariner-04/in-depth/

[5]https://interestingengineering.com/jules-vernes-space-gun

[6]https://www.nasa.gov/audience/foreducators/rocketry/home/konstantin-tsiolkovsky.html

[7]https://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/14/news/150th-anniversary-1851-2001-the-facts-that-got-away.html

[8]https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/voyager-1/in-depth/

[9]https://europa.nasa.gov/why-europa/evidence-for-an-ocean/#:~:text=What%20Makes%20Us%20Think%20There%20is%20an%20Ocean,the%20uniqueness%20of%20these%20%22Galilean%22%20moons%20was%20revealed.

[10]https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/trappist1/

[11]https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/

[undefined]undefined

Great (and well-documented!) essay, thanks!

Whoever likes these things may want to take a look at the anthology A Kepler’s Dozen. ;)

I mention few other relevant books here: here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2112.14702.pdf

Happy reading!

I just finished reading Braking Day after reading this. I very much enjoyed it. I loved the word building, characters, and very satisfying arguments in particular. Thank you.

I’m pretty sure that given that launch velocities are lower on Mars, and that we’re talking about beings that are essentially land going molluscs (Terran octopuses can be squashed pretty flat with no ill effects, and frequently squeeze themselves through tiny openings), that Jules Verne-esque gun type launchers would have been a viable transportation method for the invading Martians.

@5 Michael R Bernstein. You’re right. Christopher Priest’s The Space Machine, a recombinant pastiche mash-up of Wells’ The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, proposed that the Martian space guns launched the cylinders at lower accelerations, as you correctly surmised, due to Mars’ lower gravity. So this was survivable, even by human beings, and no fear of being reduced to raspberry jam. Priest’s afterword to his novel revealed that this was backed by calculation, performed on a computer by one Christine Priest, to prove the point.

Also, the Martian cylinders carried not only creatures like octopus-like Martians, but humanoids with siliceous skeletons. The humanoids were food for the Martian invaders. Wells’ Martians were vampires to boot. Ironically Bram Stoker published his famous novel about a certain Count in the same year as The War of the Worlds.

Wells doesn’t give any accurate information about the time between the sighting of the huge explosions on the Surface of the Red Planet and the arrival of the cylinders. While interplanetary flight times of several months, if we assume travel by Hohmann orbit, is plausible the novel itself is silent on this matter. The recent British ITV television adaptation did specify the travel time between the planets was only a week. Suggesting rather savage reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere and very impactful geobraking.

“Imagine, three habitable worlds whizzing by each other at close quarters every few days!

Interestingly, though, so far as I’m aware, no one did imagine such a thing”

Jack Vance did with the Rigel Concourse, one of the systems in the Oikumene “The Rigel Concourse: a system of 26 planets orbiting Rigel, which were moved into the system in antiquity by a vanished alien race”

I loved Braking Day; it’s one of several generation-ship novels I’ve read recently (along with Patrick S. Tomlinson’s Children of a Dead Earth series and Harry Harrison’s Captive Universe), and is neck-and-neck for my favorite book of the past year or so. A bit less hard-science than the Tomlinson, with much more fleshed-out characters than the Harrison (which feels rather dated to me now, like much classic 20th-century SF), and entirely engaging storytelling.

Please, Mr. Oyebanji, can I have more?

The progress of science regularly obsoletes the premises of SF novels (much like the breakup of the USSR obsoleted the political environment of most Cold War spy fiction), and writing styles evolve over time as well, but good storytelling tends to outlast the relevance of the particular scientific aspect an author uses as a starting point.

Thank you for the great essay. May I add something:

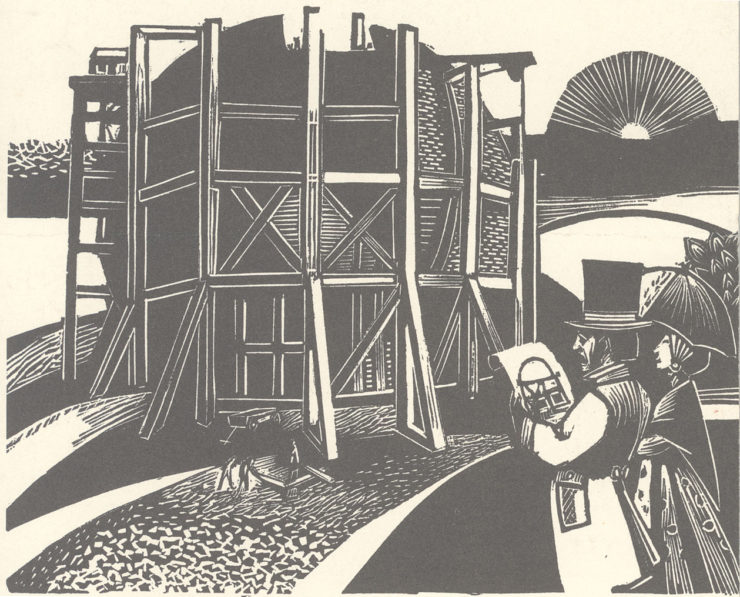

The first writer to launch a modern rocket into space was the German Otto W. Gail. In his 1925 novel “Der Schuss zum Mond” the vehicle was still fired from a long ramp. The astronauts fly to the moon, in the sequel “The Stone from the Moon” even to Venus. Gail is also the inventor of the spacewalk. This is depicted by Frank R. Paul on the cover of the first issue of Hugo Gernsback’s Science Wonder Quarterly in 1929, wherein Gail’s novel was published under the title “A Shot To The Moon.”

I remember when the Washington Post review of the movie 2010 took exception to the depiction of aerobraking to enter Jupiter orbit because (I kid you not) there is no air in space. I wish I had clipped that review and saved it, as I’m sure it was corrected in later editions.

Good to see John Carter getting defended – I saw it at the cinema. Not perfect, but definitely not bad, and I couldn’t understand why I got such a drubbing except that everyone jumped on a bandwagon.

One of the first things I ever read that involved multiple close planets was actually Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series. If you only read the many novels in the middle, it looks like fantasy… but the earliest works (at least in the internal chronology) reveal it’s actually science fiction – the dragons are genetically engineered as a solution to a cyclic near-pass with another planet in the system which allows the “thread” to cross to Pern – and the last few come back to this.

This reminds me of something:

“At the 18th World Science Fiction Convention (Pittsburgh, 1960), (Hal Clement) described a solar system he had designed in which it would be physically possible for heroes and villains to flit casually from planet to planet, as they impossibly do in most swashbuckling space opera. This came complete with two three-dimensional models and a detailed descriptive booklet (Some Notes on Xi Bootis; published as a free souvenir of the convention by Advent: Publishers), and since, Clement said, he felt he wasn’t a good swashbuckler as a writer, he threw the system open for the rest of us. Nobody has yet taken him up on the offer; swashbucklers mostly don’t give a damn.”

James Blish, The Issue at Hand (Advent:Publishers, 1964)

Maybe Jack Vance did give a damn.