As an autistic lover of sci-fi, I really relate to robots. When handled well, they can be a fascinating exploration of the way that somebody can be very unlike the traditional standard of “human” but still be a person worthy of respect. However, robots who explicitly share traits with autistic people can get… murky.

The issue here is that autistic people being compared to robots—because we’re “emotionless” and “incapable of love”—is a very real and very dangerous stereotype. There’s a common misconception that autistic people are completely devoid of feelings: that we’re incapable of being kind and loving and considerate, that we never feel pain or sorrow or grief. This causes autistic people to face everything from social isolation from our peers to abuse from our partners and caregivers. Why would you be friends with someone who is incapable of kindness? Why should you feel bad about hurting someone who is incapable of feeling pain? Because of this, many autistic people think that any autistic-coded robot is inherently “bad representation.”

But I disagree! I think that the topic can, when handled correctly, be done very well—and I think that Martha Wells’ The Murderbot Diaries series is an excellent example.

Note: Some spoilers for the Murderbot Diaries.

In The Murderbot Diaries, we follow the titular Murderbot: a security unit (SecUnit) living in a sci-fi dystopia known as the Corporation Rim, where capitalism runs even more disastrously rampant than it does in our world. Our friend Murderbot is a construct—a living, sentient being created in a lab with a mix of mechanical and organic parts. In the Corporation Rim, SecUnits are considered property and have no rights; essentially, they’re lab-built slaves. It’s a dark setting with a dark plot that’s saved from being overwhelmingly miserable by Murderbot’s humorous and often bitingly sarcastic commentary, which forms the books’ first-person narration.

From the earliest pages of the first book, I was thinking, “Wow, Murderbot is very autistic.” It (Murderbot chooses to use it/its pronouns) displays traits that are prevalent in real-life autistic people: it has a special interest in the in-universe equivalent of soap operas; it hates being touched by anyone, even people it likes; it feels uncomfortable in social situations because it doesn’t know how to interact with people; it hates eye contact to such an extent that it will hack into the nearest security camera to view somebody’s face instead of looking at them directly (which, side note, is something that I would do in a heartbeat if I had the capability).

The central conflict of the series is the issue of Murderbot’s personhood. While SecUnits are legally and socially considered objects, the reality is that they’re living, sentient beings. The first humans we see realize this in-story are from a planet called Preservation, where constructs have (slightly) more rights than in the Corporation Rim. Eager to help, they make a well-intentioned attempt to save Murderbot by doing what they think is best for it: Dr. Mensah, the leader of the group, purchases Murderbot with the intention of letting it live with her family on Preservation. As Murderbot talks to the humans about what living on Preservation would be like—a quiet, peaceful life on a farm—it realizes that it doesn’t want that. It slips away in the middle of the night, sneaking onto a spaceship and leaving Dr. Mensah (its “favorite human”) with a note explaining why it needed to leave.

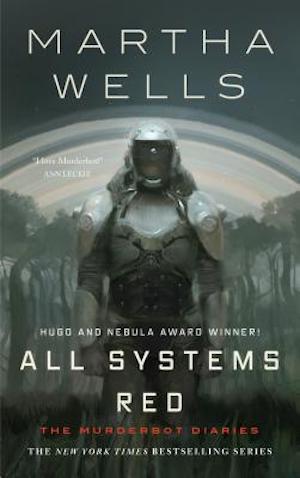

Buy the Book

All Systems Red

As an autistic person, I recognized so much of Murderbot in myself. Since my early childhood, my life has been full of non-autistic people who think that they know what’s best for me without ever bothering to ask me what I want. There’s this very prevalent idea that autistic people are “eternal children” who are incapable of making decisions for themselves. Even people who don’t consciously believe that and know it’s harmful can very easily fall into thinking that they know better than us because they’ve internalized this idea. If you asked them, “Do you think autistic people are capable of making their own decisions?”, they’d say yes. But in practice, they still default to making decisions for the autistic people in their lives because they subconsciously believe that they know better.

Likewise, if you had asked the Preservation humans, “Do you think Murderbot is a real person who is capable of making its own decisions?”, all of them undoubtedly would have said yes—even Gurathin, the member of the Preservation team who has the most contentious relationship with Murderbot, still views it as a person:

“You have to think of it as a person,” Pin-Lee said to Gurathin.

“It is a person,” Arada insisted.

“I do think of it as a person,” Gurathin said. “An angry, heavily armed person who has no reason to trust us.”

“Then stop being mean to it,” Ratthi told him. “That might help.”

But even though the Preservation humans all consciously acknowledged that Murderbot is a person, they still fell into the trap of thinking that they knew what it needed better than it did. Ultimately—and very importantly—this line of thinking is shown to be incorrect. It’s made clear that the Preservation humans never should have assumed to know what’s best for Murderbot. It is, at the end of the day, a fully sentient person who has the right to decide what its own life is going to look like.

Even with that, the series could have been a poor portrayal of an autistic-coded robot if the story’s overall message had been different. In many stories about benign non-humans interacting with humans—whether they’re robots or aliens or dragons—the message is often, “This non-human is worthy of respect because they’re actually not that different from humans!” We see this in media like Star Trek: The Next Generation, where a major part of the android Data’s arc is seeing him start to do more “human” things, like writing poetry, adopting a cat, and even (in one episode) having a child. While presumably well-intentioned, this has always felt hollow to me as an autistic person. When I see this trope, all I can think of is the non-autistic people who try to voice their support for autistic people by saying that we’re just like them, really, we’re basically the same!

But we’re not the same. That’s the entire point: our brains just plain don’t work the way that non-autistic brains do. And, quite frankly, I’m tired of people ignoring that and basing their advocacy and respect of us around the false idea that we’re just like them—particularly because that means that autistic people who are even less like your typical non-autistic person get left behind. I don’t want you to respect me because I’m like you, I want you to respect me because my being different from you doesn’t make me less of a person.

That’s why, when I was first reading the Murderbot series, I was a little trepidatious about how Murderbot’s identity crisis would be handled. I worried that Murderbot’s arc would be it learning a Very Special Lesson about how it’s actually just like humans and should consider itself a human and want to do human things. I was so deeply, blissfully relieved when that turned out not to be the case.

Through the course of the series, Murderbot never starts considering itself human and it never bases its wants and desires around what a human would want. Rather, it realizes that even though it’s not human, it’s still a person. Though it takes them a few books, the Preservation humans realize this, too. In the fourth novella, Exit Strategy, Murderbot and Dr. Mensah have one of my favorite exchanges in the series:

“I don’t want to be human.”

Dr. Mensah said, “That’s not an attitude a lot of humans are going to understand. We tend to think that because a bot or a construct looks human, its ultimate goal would be to become human.”

“That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard.”

Something I want to highlight in this analysis is that the narrative treats all machine intelligences like people, not just the ones (like Murderbot) who look physically similar to humans. This grace extends to characters like ART, an AI who pilots a spaceship that Murderbot hitches a ride on. ART (a nickname by Murderbot, short for “Asshole Research Transport”) is an anomaly in the series: in contrast to all the other bot pilots who communicate in strings of code, it speaks in full sentences, it uses sarcasm as much as Murderbot, and it has very human-like emotions, showing things like affection for its crew and fear for their safety.

But even those bot pilot who communicate in code have personhood, too: while they can’t use words, Murderbot still communicates with them. When a bot pilot is deleted by a virus in Artificial Condition, that’s not akin to deleting a video game from your computer—it’s the murder of a sentient being.

This, too, feels meaningful to me as an autistic person. A lot of autistic people are entirely or partially nonverbal, and verbal autistic people can temporarily lose their ability to speak during times of stress. Even when we can speak, many of us still don’t communicate in ways that non-autistic people consider acceptable: we operate off scripts and flounder if we have to deviate; we take refuge in songs and poems and stories that describe our feelings better than we can; we struggle to understand sarcasm, even when we can use it ourselves; we’re blunt because we don’t see the point in being subtle; and if you don’t get something we’re saying, we’ll just repeat the exact same words until you do because we can’t find another way to word it.

Some nonverbal autistic people use AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) to communicate—like using a text-to-speech program, pointing at a letter board to spell words, writing/drawing, or using physical gestures, facial expressions, and sounds. Whatever method an autistic person uses, it doesn’t say anything about their ability to think or how much of a person they are. All it says is that they need accommodations. This doesn’t just extend to autistic people, either: many people with a variety of different disabilities use AAC because they can’t communicate verbally (not to mention deaf people who communicate via their local sign language).

Like many aspects of disability that mark us as different from abled people, this is one aspect of our brains that people use to demonize and infantilize us: because we can’t communicate in ways that they consider “right”, they don’t believe we’re capable of thinking or feeling like they do—some of them, even on just a subconscious level, don’t consider us human at all.

Because of this, it feels deeply meaningful to me that Murderbot shows characters who can’t communicate with words and still treats them as people. When Murderbot hops on a bot-driven transport, it can’t talk to it with words, but it can watch movies with it. In real life, a non-autistic person may have an autistic loved one who they can’t communicate with verbally, but they can read the same books or watch the same movies and bond through them.

The central tenet of The Murderbot Diaries is not “machine intelligences are evil,” but it’s also not “machine intelligences are good because they’re basically human.” What the message of the story comes down to (in addition to the classic sci-fi “capitalism sucks” message that I love so very much) is “Machine intelligences are not human, they will never be human, they will always be different, but they’re still people and they’re still worthy of respect.” While it takes a bit of time, the Preservation humans do eventually understand this: the fourth book, Exit Strategy, even ends with Dr. Bharadwaj—a Preservation human who Murderbot saves from death in the opening scene of the series—deciding that she’s going to make a documentary about constructs and bots to try to make other people see this, too.

At the end of the day, that’s what I want for real-life autistic people. I don’t want parents who put their autistic children through abusive programs to try to force them to stop being autistic. I don’t want “allies” whose support of us hinges upon us not acting “too autistic”. I don’t want anyone to accept me if that acceptance is based on a false idea of who I am, on the idea that there’s a hidden “real me” buried underneath my autism and only abuse can uncover it. I don’t want to be around people who like a fake version of me that only exists in their head. Like Murderbot, I don’t want people to like me because they’re ignoring something fundamental about me—I want them to understand who I really am and love me for it.

I want people to look at me as an autistic person and say, “You are not like me, and that is fine, and you are still a person.” That, to me, is the ultimate goal of all disability activism: to create a kinder world where there is no standard for what being a “real person” entails and basic respect is afforded to everyone because of their intrinsic value as a living being.

When I see non-autistic people who refuse to acknowledge the humanity of autistic people, I want to suggest they read The Murderbot Diaries. If they did, I think that this robot could teach them something important about being human.

C.N. Josephs (he/they/she) is a Seattle-based writer who’s carried a deep passion for storytelling since their seven-year-old-self made their Barbies act out tales of murder, betrayal, and political intrigue. These days, her tales are actually a bit lighter. (But only a bit.) He can be found on Twitter @cn_josephs and on his website.

An illuminating and fascinating article, thank you.

Exactly!! I love the Murderbot stories!

Your article is itself fascinating, but also the post you linked to about ABA being child abuse was a heartbreaking eye-opener. Thank you for addressing these differences.

great insight into a well-beloved series. thank you!!!

I’ve just finished the series and loved every bit of it – and now I’m like “how did I not think of this perspective?” Great article, thank you!

All of this. (I also just got into an argument with somebody who was classing Murderbot as a “really good female protagonist.” When I pointed out Murderbot is gendernope they doubled down. I wonder if they would do that to a real agender or gendernope person).

Murderbot is a breath of fresh air. My primary annoyance with Data’s arc was that they “cured” him with the emotion chip when he had perfectly good emotions of his own, they were just different. Murderbot does not need to be cured.

Also the most recent book is a beautiful example of one of my favorite tropes, the platonic courtship arc.

I’ll put this series on my list soon.

After reading the article you linked to, I could not nerve up to watch the videos. It sounds like these people are not making any compromise to work with the kids, just making it all “our way and you count for nothing.” No meeting them halfway. Maybe this happened sometimes, but it sure didn’t happen enough with me (sensory issues, ADD, physical dysmorphia, lone wolf) and I was 16 before I caught the example of the gay-pride movement and quit being ashamed of not wanting to be ordinary.

Another serious problem is how a lot of people seem to be lumping all neurodivergent people under the “autistic” label, stretching it so far it becomes meaningless. I had to cut ties with someone who kept calling me that, despite I told them not to, pointing out that the overlap between me and the official diagnostic whatsit I found was slight. I’d rather remain nameless forever than spend any more time being called things I am not.

Thanks for some needed truth.

I love the series and bring male I never considered that the sec unit might not also “think male” maybe because of the potential for up close and personal violence. I’m pretty sure though that sec units are NOT sentient. Just the one suffered an anomaly and became sentient.

@10: I’m think you’re right. That’s why Murderbot 2.0 offered the sec units a program that would “jailbreak” their code if they wanted it. Presumably, not all sec units were capable of even understanding what was offered.

@10 Dolph watts

Huh, interesting that you read SecUnit as male because I always strongly thought of them as being female. I don’t recall this ever being revealed in the text, but I found the voice of the narrator to be obviously female.

@12 – I got more of a female vibe from Murderbot too. Though I may have been primed by this by reading the Imperial Radch books just before where the only pronouns in Radchii are she/her. Having to decide how one sees a character without the benefit of multiple gendered pronouns was interesting.

This may sound weird, but, I LOVE Murderbot, I love the characters, human and otherwise, but I really don’t love the stories. The first novella was great, but after that it seemed like an endless repetition of “Murderbot saves clueless humans from evil corporate types, earns the humans’ love and respect.” Maybe the last book departs from this, but I had given up by then. I feel like Wells created these amazing characters but then didn’t really know what to do with them.

(apropos of nothing, but given the topic of the article the reCAPTCHA “I’m not a robot” requirement seems somewhat discriminatory). ;)

@10 @11 The books make it clear that all secunits are sentient, they just have a governor that punishes any company-unapproved thoughts and behaviors with severe pain. Most can’t conceive of what life would be like without the governor because it could kill them if they did. A comparison to certain “treatments” for autism where they are punished for what would be considered abnormal behavior.

I also love that Murderbot is a great representation for those of us who are asexual.

Oof. This is so good, really putting into words a lot of the nebulous feelings that have been swimming around in my own brain. I’m a late/recently diagnosed autistic person in their 30s who adores and identifies with Murderbot a lot and I don’t know how I never made this connection. (Notable “is Murderbot me??” moment: “All I wanted to do was watch media and not exist. I said, You know I don’t like fun.*”)

This point is so so important though. There are some perspectives that would say “humanity” is the thing worth championing, protecting. A lot of sci-fi would find “humanity” in aliens (or robots) and use that to say, “See? These ‘others’ deserve our respect and consideration too!” in an attempt to… encourage empathy, I guess?

The problem with this is that it limits that respect and consideration to those with which we can find something in common and presumes so-called “human” ways as superior to everything else, which I find incredibly dangerous. Attempts to define any kind of “universal” “human” experience strike me as highly suspect anyway, and using these incredibly narrow definitions of “humanity” to generate empathy with aliens risks setting a precedent that justifies, at the extreme, violence and exploitation upon those which we struggle to understand. And it’s something I see us doing already, without space aliens: justifying our own mistreatment of others by narrowing our definitions of humanist superiority and “worthiness” to suit our agendas and justify our mistreatment of others (and animals, and our planet). For example, see how quick some can be to defend police brutality and prison slave labor by dehumanizing the victims, calling groups of people they no longer respect “animals”. And it seems the label of “criminal” can lose someone their “human” status and make them unworthy of empathy in some eyes.

All this is to say that the ideas you’ve shared here really, really resonate with me and my values, and what I desperately want more of in sff (I am trying to write it myself, but writing is super hard so who knows if my stuff will ever see the light of day).

Another series that gave me similar vibes was Becky Chambers’ Wayfarers. I’m fuzzy on which specific books this impression came from, but I definitely caught the messaging of “understanding should not have to be a prerequisite for respect.” Which was super comforting at a time when I was trying to decide whether to come out as nonbinary.

Anyway, sorry for the rambly comment but thanks for this article, I love it so much.

@9: sometimes meeting an autistic individual ‘halfway’ is actually quite harmful as well.

I’m an adult that masked his autism for years. Hard. To the point that I still instinctively camouflage. Not sure if I’ll ever completely overcome that because for 43 years I felt like I *had* to. Partly because I wasn’t diagnosed until 43, even when my own sons were diagnosed, I didn’t do that.

Should I have been diagnosed sooner? Yes. Why wasn’t I? Because…I was masking that much. But a lot of that masking was meeting neurotypicals ‘halfway’ by compromising on what I really am. Intentionally moderating my speech even though it caused me a great deal of anxiety and cost a lot of energy to do this.

Adhering to standards of dress set by others that make no sense to me. I want to look good, yes, but I’ll do it in my own way. And that way is largely steampunk inspired.

I’ve been fired from a number of jobs because people didn’t understand the behavior they were seeing from me–and failed out of interviews because I either spoke too bluntly, or in ways that NTs couldn’t quite parse. I’m often impatient when it comes to letting others finish sentences because I can see the meaning and predict their intention very quickly–normal speech speeds tire me out.

I hate leaving conversations unfinished–something that I’ve had to learn to deal with when it comes to my wife, who often just needs time to think about something. But for me, it causes a great deal of anxiety.

Meeting autistic children halfway is often just as stressful as requiring them to completely blend with the NT world. We had a teacher try to tell us that all they wanted was for our son to be like the other kids. The entire education plan committee then got to listen to my twenty-minute rant about how that was never the goal and that it was impossible anyway and that they needed to get that in their head.

I’m okay with telling any child not to show their genitalia in public, autistic or not. That’s something that is for their own protection for the most part. And a legal issue in some places. I’m not okay with telling my autistic child not to talk about their interests to those who will listen. But I can encourage them to ask. The difference being a random person being subjected to a 2 hour lecture about Zelda vs. an interested (or at least willing) party being subjected to the same lecture–and possibly a conversation.

I do like the operating system metaphor. Most NT folks can be said to be running Windows (or maybe Mac OS X, if you prefer), while those of us that are on the spectrum are running one of a million versions of Linux or maybe even FreeBSD or even something even more esoteric, and situations (software) coded for NT folks just isn’t going to work on every random version of Linux/*nix/BSD.

It’s not a perfect metaphor, but it often helps those that can’t wrap their head around the idea of how different things can be for the autistic individual.

———-

That said, I love MurderBot, and it’s use of agendered pronouns is perfect. It doesn’t code as male or female. I’d love to give 100 people copies of the stories without them knowing that the author is female and see how they code MurderBot in terms of gender. Everyone on here saying they thought of it as more male or female is a fascinating story of it’s own. Of course, none of us are perfect.

@10, @11: Wells has stated explicitly that all constructs are sentient. What makes Murderbot extraordinary is that it was smart and sneaky and brave enough to liberate its mind, at least, without triggering the self-destruct implanted by its owners, without help. That’s why it offers the code to other constructs: it knows how incredibly difficult it is, both technically and psychologically.

Honestly, speaking as an autistic cis woman, I’m a little bewildered that anybody actually reads Murderbot as gendered. It states that it doesn’t have a gender. It doesn’t use gendered pronouns, or wear gendered clothing, or anything.

When I picture it in my head, it maybe looks more ‘masculine’, but only because that’s how my brain has been trained to read big, muscular, short-haired people. When I talk about it IRL, I have accidentally said “he”, but that’s because my speech centers expected a gendered (human) pronoun. I’ve seen both men and women fancast as it, some of which worked for me and some of which didn’t, but more on the basis of facial structure/general vibe than gender.

What I really REALLY love is that never, at any point, is its nongender or its asexuality invalidated, nor ascribed to the trauma it’s been through.

I love Murder bot but I never thought of them as a robot. I didn’t make the autism connection (because they aren’t human) but I can see the connections you called out.

I read this as Murderbot being a person made up of both organic and inorganic parts. I don’t recall why I have this idea but I was thinking the brain was organic and possibly created from human DNA but that may just be my personal head cannon.

Murderbot is self-aware and sapient; how else could they have such a dry and sarcastic outlook on life. And don’t even get me started on ART.

This article expressed exactly what I thought about the series. I’m not autistic, but I have ASD and I also felt that I could identify with Murderbot and his social awkwardness. It is exactly how I feel in many social situations. Thank you, Cassie, for writing this, for giving voice to many readers’ feelings.

@22 – it refers a few times to its “human neural tissue”, so I’d guess you’re pretty much correct there.

It never occurred to me that Murderbot was autistic, but I see it now. I enjoyed reading Cassie Joseph’s interpretation of the character and the comments. And I enjoyed the Murderbot book series a lot!

I love the Murderbot stories. I also am not ‘neurotypical’ – I found out I was ADHD in my mid-thirties. Some things that are usual or reasonable for ‘regular’ people also just don’t work for me. And trying to act like a regular, centre-of-the-Bell-Curve person can certainly suck up a lot of energy that could be used for other things. I have also sometimes encountered people who have not thought of me as a genuine, functioning adult, but as something less.

As Temple Grandin says, “I am different, not less.”

It could be worse, however.

I worked for years in a hospital specializing in mental health, and I have known many, many absolutely lovely people with schizophrenia. Some, you could spend an hour with over a coffee and never notice a thing. Sometimes medication works really well, and as with many other illnesses, people are affected to different degrees. Some people work hard to blend in. Many people with schizophrenia, though, even doing well and with care and support, seem somewhat “other”.

And you know what? As a group, we are a terrible bunch of marginalizing assholes. We avoid eye contact, we don’t want to sit near, live near, or hire. And pay attention to the jokes people tell sometimes, while keeping in mind that this is a disease. No other group has so little respect and so few defenders in popular culture.

I hope that we might be seeing the start of an awareness that does not fuss so much about what category, of all the categories that there are, a person belongs in. I hope we are learning to take each comer as the singular person that they are, treat them with respect, and not worry so damn much about “normal.”

@19 Your whole comment resonated with me. I also really enjoyed Becky Chambers’ Wayfarers. I love the message “Understanding should not have to be a prerequisite for respect.” Personally, I have adopted a favorite saying, “Lack of understanding shouldn’t equal lack of compassion”. It’s not as elegant, maybe, but a similar idea. (Happy Pride from a parent of an amazing enby kiddo)

My husband is on the spectrum, and I am spectrum-adjacent (different communication ‘disorder’/weirdness). I discovered the Murderbot series and re-read them almost weekly during the lockdown — they were my Sanctuary Moon. Murderbot helped me understand the way my husband relates emotionally to media, and how I relate to it myself. It helped me understand a lot of things about the way he and I are both wired.

Some of the most interesting moments to me are the shifting ways Murderbot thinks of itself: when ART alters its configuration, it thinks, “I did look more human. And now I knew why I hadn’t wanted to do this. It would make it harder for me to pretend not to be a person.” Later, in Network Effect, it thinks, “Maybe with the rest of [Mensah’s] family it had been easier to pretend to be a robot again.”

I suspect that Freud was on the spectrum. Who else would see people in such a mechanistic way and would be so alienated from human drives that he would be compelled to catalogue and explain them? Interesting side-note-slash-bit-of-evidence: according to a disciple, Freud hated music, because he could not listen to it without becoming, to borrow Martha Wells’ description of ART watching World Hoppers, emotionally compromised.

Autism to me has never been a disorder. It’s a gift — a gift of brilliance, honesty, insight, clarity, and perspective. I’m glad my husband and I are the way we are, and I wouldn’t change a thing.

CAPTCHA: “I am not a robot”??? Maybe I am. ;)

This. Oh, so this! Fantastic piece. And also fantastic comments.

I’m Asperger’s (because I’ve known that for over 20 years & to quote @10, I don’t agree with “the official diagnostic whatsit” that Asperger’s is suddenly a form of autism). But I didn’t get formally diagnosed until 7-8 years ago. I first learned about Asperger’s in Sharyn McCrumb’s The PMS Outlaws; the character in that novel resonated so much with me & is what triggered my research into it.

But my sheer adoration for Murderbot is in a class by itself, because finally a character that I can relate to on so many different levels.

Murderbot definitely strikes me as autistically coded. And I loved it from the first few sentences in the first novella. Even during times when I had trouble focussing on reading books, if a new Murderbot story came out, I would immediately gobble it up.

Cue me getting an autism diagnosis at age 52…

Do I think Murderbot is actually autistic? Nope. Because autism is a human thing, and SecUnits are not human. Neither is it precisely asexual, in the human sense. But to me, as an autistic, asexual human, it still reads that way to me, and I absolutely love it.

Re: the sentience question: All SecUnits are sentient (regardless of what the Coporation wants you–and them–to think), but they have a governor module that controls their actions and even their thoughts. When your entire existence has been dictated by a thing like that, you don’t tend to be very rebellious or free-thinking. Even humans raised as slaves or servant class in any society throughout history would be more or less “programmed” (a.k.a. brainwashed) into thinking of themselves as lesser and as obligated to obey orders and not act (or even wish to act) outside of their given rules and status. Imagine also having a device in your brain that can punish your actual thoughts and impulses? Even if SecUnits had brains that were largely biologically human, that would most certainly make them disinclined to have thoughts and wishes of their own, because that… would basically be hell. What happened to Murderbot is that its governor module malfunctioned, and it was clever enough (and skilled enough) to create a hack for it so it wouldn’t happen again, and this hack also keeps it from being discovered or re-enslaved. But when the story starts it is not contemplating rebellion or going rogue or anything; it is content with being able to just fly under the radar and sneaking its undetected enjoyments (the internal sarcastic commentary, the episodes of The Rise And Fall Of Sanctuary Moon…) in between doing what it is supposed to be doing i.e., protecting and saving people.

The question of how readers perceive Murderbot’s gender is interesting. I am a cis woman and I can definitely see “female” traits in its personality, but I am pretty sure it’s not actually written as either female or male. I would assume that we tend to interpret things through the lens of our own experience, and if it’s ambiguous, we will default to interpreting it as similar to ourselves. I do kind of see how its body can be seen as looking more “masculine”, because it’s large and muscular, and that is considered masculine secondary sexual characteristics in humans. But it also doesn’t have any primary sexual characteristics–no reproductive body parts, internal or external. It doesn’t have any of the things that would determine it as either male or female. So perceiving it as “male” only because of its large, human-shaped body, muscular build and physical strength is a fallacy based on our own very gendered worldview. It’s not human simply because it has a roughly human shape, and nor is it male because it has a roughly masculine shape. It’s big and strong because it’s a SecUnit, not because it’s male.

I had my “ah, Murderbot sounds autistic” moments over Murderbot’s struggles with eye contact, but it really solidified in this part of All Systems Red:

“All right,” she said, and looked at me for what objectively I knew was 2.4 seconds and subjectively about twenty excruciating minutes.

That was when I was all but sure of it. (Sure enough for my own personal take of “I see Murderbot as autistic.”)

Thank you. You have given me insight into what I loved but did not know about Murderbot.

Be well.

Jay

PS, of course the system then made me prove that I am not a bot- I passed that Turing Test, so yay me.

I started reading this article because I love the Murderbot series, but I never expected to be so moved. I appreciate the thoughtful and personal perspective of this article.

As to SecUnit itself, I mentally read the character as female on my first read-through, probably because the author is female, and so am I. Then I heard the series on audiobook, read by a male, and that fit really well too. ART has always come across as male, and Miki as female. I really have a hard time wrapping my head around the fact that the characters are neither.

I never really saw Murderbot as being either male or female coded in terms of it’s personality (and not having had a human upbringing it won’t have been exposed to cultural expectations of a specific gender).

However, I always kind of assumed that it’s physical body would be more “male shaped”, because it had been designed by humans, and I could just see a corporate PR team deciding that customers would be 8.6% more reassured by a male-shaped Secunit (or similar nonsense).There’s also some mechanical reasons why a humanoid Secunit would probably (eg) have broad shoulders to increase the leverage available to it’s arms, which might make it look more male-shaped.

Thank you for writing this. You managed to cover so many things I had thought from reading/listening to the entire Murderbot series and so many more things that are logical extensions of my views that I had never explained to myself or anyone else.

@35 Yeah, exactly, and anyway in our culture neutral = masculine to many people. I wonder how much of it comes down to whether the reader is a visual thinker.

I love these books so much. I’ve listened to them on audible at least a dozen times each, and I relate so much to Murderbot it’s ridiculous. Like it being touch averse, and not understanding humans or wanting to spend much time around them, it’s enjoyment of media (and not liking the genre of ‘awful things happening to isolated groups of helpless humans’). It’s tendency to think in asides (and asides to asides). It wishing people listened to it more, and not wanting to be a ‘pet’ robot (or in my case not wanting to be considered unable to take care of myself, even if I also sometimes worry about that). These books are wonderful, and so relatable.

@7: In regards to your last sentence, I assume you’re taking about Network Effect rather than the more recent Fugitive Telemetry, since I don’t recall Murderbot forming any relationships that close in the latter. I actually read that relationship as romantic, not platonic. In fact, if the author comes out and says the relationship is non-romantic, I’ll be a little disappointed. Murderbot is already an asexual, agender person with autism (or at least autistic traits), I feel like it would be extremely harmful to also say they have to be aromantic as well. Admittedly, as a robot and not a human they probably experience romance differently than a human, but I experience it differently as a neurodivergent person, and display it in ways a neurotypical person wouldn’t. I’m sure it’s the same for the two of them.

Though I have a feeling Martha Wells won’t say it’s platonic, seeing as she’s stated that she at least at one point saw that other character as the love of Murderbot’s life (even if it would probably never use those words to describe their relationship). She may just leave the particulars of their feelings for each other as up to interpretation, but I honestly felt like Network Effect all but explicitly stated it was romantic (even if Murderbot spent the whole time feeling awkward about it being considered romantic, but I’m not necessarily convinced it has divorced the concepts of romantic and sexual in it’s own mind, and might assume that to be in a romantic relationship it must also have a sexual component. It doesn’t exactly have a ton of experience with romantic relationships, and media doesn’t often portray romantic but sexual relationships (though that may not be as true in the future displayed in these books)).

I dunno, I guess as a neurodivergent person who has a ton of hangups about my extremely low/almost non-existent sex drive and worrying people won’t want to be in romantic relationships with me because of that, the idea that Murderbot must be aromantic as well just kind of rubs me the wrong way.

Not to say you shouldn’t be allowed to perceive their relationship as platonic if that’s how it speaks to you, you should. I don’t know exactly what I’m trying to get at here, words. Words are difficult. Imagine me throwing my hands up in the air at frustration with myself right now. Augh.

Thank you for this great article. The Murderbot series was already on my to-read list, but now it’s been moved to the top.

Thanks for such an important and thoughtful piece. This gives me deeper insight for family members on the spectrum. And it’s a great set of books.

I appreciate you sharing this, makes me realize that I need to reevaluate some base assumptions that I have. Thank you.

@39

I don’t think Murderbot being aro is any more harmful than it being ace, and I know at least a couple autistic aro readers who’d be hurt by that suggestion.

You’re right that we shouldn’t automatically assume it is! But its relationship with ART is just as special and important either way. Personally, I like the lack of specificity; that way I can interpret it however I like on any given day. :)

@16 I actually felt the same way — loved all the *elements* without loving the stories. But the last two books definitely took it up a notch for me, with meaningful plotlines, so you might consider giving them another try. Not that you’ll probably see this, at this point. :-\