It’s the understatement of the century to say that COVID-19 has led to irrevocable changes in our global society. In events, in the economy, and in culture. For the science fiction and fantasy community, one of the most visible changes was when the Hugo Awards took the form of an online ceremony for the first time in 2020.

Yet, somewhat ironically, it was in 2021, with the Hugo Awards eschewing the virtual world and returning to an in-person ceremony, that they decided to issue a special honour: an award for Best Video Game.

“For many, video games are the main way to experience science fiction and fantasy storytelling,” said co-host Andrea Hairston. “Expansive series like Mass Effect, Horizon Zero Dawn, and Final Fantasy have shown that games are now more than play. They’re lived-in spaces where players are free to explore new worlds, new stories, and new identities.”

It’s certainly true that in a stunningly short period of time, evolutions in technology have evolved so quickly that people who were coding some of the earliest programs are still alive today, experiencing virtual reality, wholly interactive experiences, and far more in-depth stories than were possible when they started their careers.

But while Hairston and co-host Sheree Renée Thomas did acknowledge the long history of video games by mentioning Bertie the Brain, a Canadian-made machine built in 1950 that could play tic-tac-toe, it’s important to also acknowledge that the line between literary science fiction and fantasy and the virtual world has been blurred almost for as long as the medium of gaming has been publicly available.

The earliest games were made and played on machines that were largely inaccessible to the general public, like MIT’s Spacewar!, which was built on the university’s PDP-1 minicomputer (a misnomer if there ever was one—the “minicomputer” weighed 730 kilograms). They were also the purview of the minuscule hacker and programmer community, which again, proliferated in universities but was as scarce as the dodo bird elsewhere. However, while arguably “SF&F” in style, these were not mediums for storytelling.

It was only in the ’70s—when gaming became commercially viable with the advent of personal computers and home consoles, along with the introduction of accessible programming languages like BASIC—that gaming suddenly became a place for telling tales.

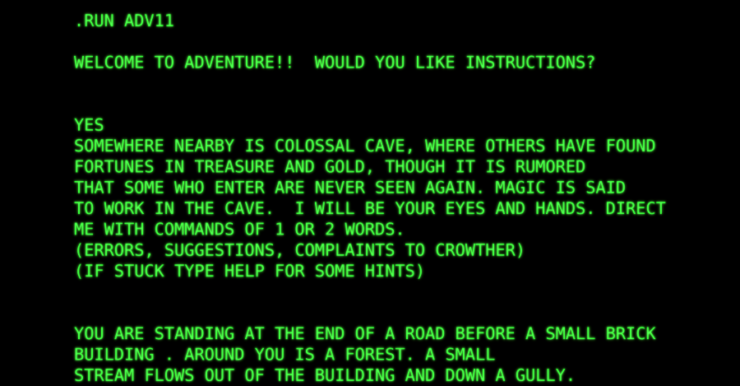

In 1972, programmer William Crowther was working at Bolt, Beranek & Newman in Boston, alongside his wife Pat. Crowther was an avid cave surveyor, and used his skills with programming to send survey data remotely to a teletype in his living room. When his marriage to Pat ended in 1975, William, feeling estranged from his two daughters, decided to write a game that would simulate his caving experiences, which he hoped would bring him closer to his children.

Crowther’s daughters would be introduced to the world of Colossal Cave Adventure, widely recognized as the first text-based adventure game. It was through the efforts of another programmer, Don Woods, who found the game on a university computer at Stanford, that Colossal Cave Adventure was then widely distributed for the public, with Crowther’s blessing.

Two big fans of the game were MIT students Marc Blank and Dave Lebling. Lebling was also a tabletop gamer and huge fan of Dungeons and Dragons, so much so that he built a program to aid him in playing the iconic fantasy RPG.

Lebling and Blank, as well as fellow MIT students Tim Anderson and Bruce Daniels, inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure, set about making one of the first fantasy adventure video games: Zork, first released in the university community in 1979. Meanwhile, in the literary world, books were also becoming more interactive, both with Dungeons & Dragons and with the 1976 release of the first Choose Your Own Adventure book.

Thus, Interactive Fiction was born.

In these seminal steps, the blurring between video games and literary science fiction and fantasy was established from the get-go. Infocom, the studio founded by Lebling, Blank, Anderson, and several other co-founders, was particularly known for pushing the idea that fiction could be something audiences interacted with.

Titles like A Mind Forever Voyaging and Planetfall were embraced as superb science fiction yarns, The company would even issue novelizations of its games, including the 1989 adaptations of Enchanter (first released as a game 1983) and Stationfall (first released as a game in 1987), the sequel to Planetfall.

Infocom is famously known as the studio that somehow managed to make a video game based on the already-adapted Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the radio play-cum-novel-cum-TV series-cum everything. The adaptation of literary science fiction to video games would reverberate well into the ’90s, with cult classics like Cyberdreams and The Dreamers Guild’s adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream or Psygnosis’ Discworld game, which borrows mainly from Pratchett’s Guards! Guards!

The interest was not one-sided, either. Foundational works in literary science fiction and fantasy like Neuromancer and Snow Crash had gaming and programming in their blood. These novels recognized the inexorable cultural pull of technology, and foresaw a future where the virtual world would, in many ways, overtake the real one. Other stories like Larry Niven’s Dream Park offered a look into the potential future of e-sports or gaming competitions. Technology was hurtling forward, and gaming was a core component, helping to drive that momentum.

Buy the Book

A Prayer for the Crown-Shy

Evolutions in technology meant that, oddly enough, the mediums were separating again, in a sense, moving from the text-based work of Infocom to point-and-click output of studios like LucasArts. It is this separation which may, ironically enough, be why video games haven’t been taken seriously as a storytelling medium, broadly speaking, until more recent years.

Yet even in the apparent branching off of video games into their own unique kind of storytelling, the core foundation remained the same. Players may have interacted by clicking instead of typing, and by watching characters talk instead of reading, but story and worldbuilding were central to gaming. Programmers would be crafting narratives, and the foundational programming language of “use—object—on—interactable” still existed in the background of code.

Indeed, the literary aspects never really left. One need only look at works like 1999’s Planescape: Torment, which was jokingly referred to by gamers as “the best novel you’ll ever play” and by Macworld as “A text-driven masterpiece,” to see how literary sci-fi and video games were always running alongside each other. Planescape: Torment is estimated to contain around 800,000 words in its script—a word count which one writer aptly observed is 30 percent longer than War and Peace.

Even today, some games persist with mainly text-driven stories and playstyles, like the award-winning 2019 game Disco Elysium, developed and published by ZA/UM with Estonian novelist Robert Kurvitz as the core narrative writer and designer. It is a testament to the power of its writing that Disco Elysium is the highest-rated PC game on review-aggregate website Metacritic.

All of this is to say that it is a thrill to see that video games are finally getting their due credit in the cultural discourse. While the Hugo Award for Best Video Game was ostensibly a one-off, the rumour mill has it that it could become a permanent fixture.

If anything, the history of gaming and its significant overlaps with literary science fiction and fantasy prove that this recognition has been a long time coming. This is a medium which, more than anything, was founded in a spirit of empathy—that of a father hoping to reach out to his daughters and create a world, and a story, in which they could all take part. Indeed, storytelling is fundamentally about empathy—a way of engaging a reader’s emotions through themes and characters, pushing that reader to a place of understanding and connection. This drive toward connection and empathy has been a part of video games since their very inception, and it’s time that we recognize and celebrate video games as a storytelling art form in their own right.

These are the stories that shape us. These are the stories we played, and shared with others, and which continue to shape the imaginations of future readers, writers, gamers, and artists.

Tim Ford is a writer and freelance journalist based in Victoria, Canada. He has had bylines with CBC News, the Toronto Star and the National Observer, and SF&F stories with Neo-Opsis Magazine, Crossed Genres Magazine and EDGE Science Fiction and Fantasy. He also has a pitbull-corgi cross and can be found @TimFordWrites on Instagram and Twitter.

I remember lines and situations from early games as well as I do books from the same era, sometimes better.

You are about to be eaten by a grue.

OMG! I remember playing Adventure at a party in 1979 where the host had a home terminal connected to the mainframe computer at Boeing, where some programmers had loaded the game (don’t tell Boeing management). I was so engrossed in it that my wife finally had to pull me away. I also remember asking the host to come look at something I had discovered, and she said “huh, I never thought of going ‘up’ at that point”. I was so proud of finding a way out of a locked room!

You really had to work your powers of visualization with that game, Basically, it was the first interactive story. Marvelous! Thank you, Messrs. Crowther and Woods.

The Digital Antiquarian has been writing a history of computer gaming for eleven years now, and for those interested in the subject I cannot recommend them nearly enough.

I can remember computer-game rooms at Lunacon during this era, with terminals set up so people could take turns playing “Colossal Cave Adventure,” with many of us getting stuck at:

“You’re in a maze of twisty little passages, all alike.”

I loved all those Infocom text adventures. My favorite was “Bureaucracy” where the goal was to get your bank to accept a change of address before you have to fly to Paris for a new job. It was the funniest computer game I’ve ever played. And it was written by Douglas Adams, based upon true incidents in his life.

As well as the published titles listed, people continue to write excellent IF and make it freely available – and with such compilers as TADS it’s never been easier to write your own!

Worth a footnote mention of Scott Adams, who made some of the first commercially available text adventures back in the TRS-80 era ….

It may also be worth a mention that this is a different person from the Dilbert cartoonist.

Well, the times are definitely not over. Keyword: Visual Novels. Such japanese text-adventures are more popular than ever before and tell stories so uniqie I have never seen anywhere else (Zero Escape, Umineko, House in Fata Morgana). All criminally underrated fiction I would call literature than certain real novels.

Tracker Books were surely the start of interactive fiction. Mission to Planet L was published in 1972, predating D&D by 2 years.

The business meeting at the Worldcon just concluded in Chicago passed a proposal for a new Hugo for Best Game or Interactive Work. It would of course include video games, which are likely to comprise many of the entries, but the proposal is designed to be medium neutral.

If it’s passed at the next Worldcon then it becomes a permanent category, and would then be in place the following year. That, of course, does not keep any intervening Worldcon from doing it as a one-off again before such possible passage.

Yay Colossal Cave! That was the first game I played on our computer, growing up (late 80s). Something about not having a graphic interface made it simultaneously creepy and deeply engaging.

Also: “PLUGH!

ADVENT arrived at GSFC (and our 360/65) as a FORTRAN card deck (this was about 1980). We got it to compile and run under TSO…and about a week later were told to remove it by the systems programmers, thus leading to our trying D&D instead and introducing me to TTRPG’s.

I loved text adventure games so much!! CC Adventure (XYZZY!), The Scott Adam’s Adventures (#5!!), and of course all of the Infocom games! Wishbringer, Hitchhiker’s Guide, Leather Goddesses, The Lurking Horror, Nord & Bert, Trinity, and of course the Zorks. They were still releasing games when I graduated high school even though I started playing them around 1981.

I’m pretty sure I have both of the “Treasures of Infocom” around here somewhere…

“Softporn adventure” was the first (and not the last) game I played from Sierra Online, which was later released as Leisure Suit Larry with graphics. (yep, I was pretty much a pre-teen girl when I played that! I was pretty low on games since I was using my brothers!) And then the graphics/text combo, Wizard and The Princess with cassette load on my cousin’s commodore 64. (Cassette load took FOREVER if it even worked.)

And of course the ascii dungeon games, like Hack and Omega. (And Rogue, but I didn’t actually play that one much!)

Ahhh the 80’s were the best.

Don’t know whether anyone in reading distance has ever heard of it, but in the early-to-mid 70’s, apparently from the Center for Advanced Computation (CAC) at the University of Illinois, was a D&D-type online game, called “Empire of the Petal Throne”. I wasn’t into gaming, but many of my cohorts where I worked were extreme fans of this game, and they’d discuss “EPT” endlessly. Since I expected to hear at least one comment about it, the game must have been a regionalism. But CAC was world-reknowned at the time (remember HAL-9000? Developed by the CAC, University of Illinois, according to Clarke…)

I adored text adventures! I played Hitchhikers so many tines, and still remember the chapter that started:

“You awaken in the dark. You can see nothing, hear nothing, feel nothing, and smell nothing.”

I have the novelization of Wishbringer on my bookshelf too. I loved the computer text adventures, because they weren’t as short as the Choose Your Own Adventure books .They made my little geek heart so happy!

I remember playing Zork while at school, mostly from the physics department’s connection to the university’s DEC System 20 mainframe. Our connection was over a dial-up acoustic coupler modem (yep, the type where you stuck the phone’s receiver into the modem’s cradle), the terminal a TRS-80 acting as a dumb terminal for that purpose.* You could only play when it wasn’t busy, lest you find yourself unceremoniously disconnected.

*(IIRC even by then they were being referred to as Trash 80s.)

There was once a segment on The Simpsons where it was horrifyingly clear to me that Homer Simpson was about to get the Babelfish (stumbling through the mail on the porch and other things familiar from Hitchhiker).

All those games are memorable (the command ‘get blaster’ is often chanted by me while watching cop shows).

Ah yes, we remember them well…

@16 – Empire of the Petal Throne was a tabletop RPG, released in 1975 by TSR as a separate game rather than as a supplement to Dungeons & Dragons. I suppose it was popular enough among the gamers at your school that someone coded an online version, much as online versions of D&D itself were probably being written by people at the time.