John Brunner was born eighty-eight years ago, on September 24, 1934. He died just short of his sixty-first birthday, on 25 August 1995, while attending Intersection Worldcon in Glasgow. Between the years 19511 and 1995, Brunner wrote dozens of science fiction, fantasy, horror, and mystery works2, many of them award-winning.

While I expect that many of my readers will have read and liked Brunner novels, I would not be surprised if other readers, perhaps a majority, have not had firsthand experience with his work. Therefore, with the melancholy anniversary of Brunner’s death just past and with his birthday coming up, this seems a suitable time to suggest some Brunner works to the tsundoku of those unfamiliar with this author. Here are ten3; the last four are award-winning works generally agreed to be among his best.

John Brunner by Jad Smith (2012)

First up, a monograph not by Brunner but about Brunner. Although just 184 pages long, of which just 127 pages are the monograph proper, this is a compact, fascinating examination of Brunner’s life, career, his ambitions, and the constraints under which he struggled. The only thing I might critique is the brevity. Who knows? Perhaps if a few thousand of you purchase the monograph, Smith will compose a longer work.

The Stone That Never Came Down (1973)

Some might claim that Brunner was incapable of writing an upbeat novel, that some hook was always hidden even in the most cheerful of endings. This book is proof to the contrary: In a world torn by familiar conflicts, a novel substance, VC, offers the world a gift its leaders do not at all appreciate. VC makes humans discerning and critical. Doublethink and self-delusion lead to distressing cognitive dissonance4; negative feedback shuts them down. VC could eliminate human folly and save the human race from itself… if the people whose rule depends on folly do not discover its existence in time to suppress it.5

Total Eclipse (1974)

Total Eclipse, on the other hand, is exactly the sort of Brunner novel that made The Stone That Never Came Down so surprising. The Draconians of Sigma Draconis III left behind a wealth of artifacts but no descendants. All Draconians perished after a mere three millennia of advanced civilization. The thirty human researchers stationed on Sigma Draconis III hope to learn why such a promising culture vanished so completely. The answer will bring no comfort.

The Compleat Traveller in Black (1982)

The Traveller in Black “had many names, but one nature, and this unique nature made him subject to certain laws not binding upon ordinary persons. In a compensatory fashion, he was also free from certain other laws more commonly in force.” The immediate consequence is the ability to warp reality according to the whims of passers-by. Five novelettes reveal the wonders that follow the Traveller’s “As you wish, so be it.” The morals of the stories: one should be very, very careful about what one wishes for.

Times Without Number (1974)

Following the triumph of the Spanish Armada, Western civilization flourished. However, with technological advancement comes hazard. Time travel is so dangerous that rival powers have signed the Treaty of Prague, which regulates the practice.

Don Miguel Navarro, Licentiate in Ordinary of the Society of Time, is one of the functionaries charged with enforcing the treaty. However, not only can profit inspire men to circumvent the Treaty of Prague, so too can national ambition. Over and over again, Don Miguel is faced with preventing temporal crimes. If he fails even once, history as he knows it may be erased.

The Crucible of Time (1983)

The promising alien civilization that features in this highly episodic fix-up novel has the misfortune to live in a solar system traversing a region of interstellar space far denser than the region in which our Solar System currently resides. Consequently, global catastrophes are frequent. Over and over, the aliens claw their way back to civilization only to be smashed flat once more. With time and effort, they might be able to escape the deathworld they call home…but time is not an asset they have in abundance.

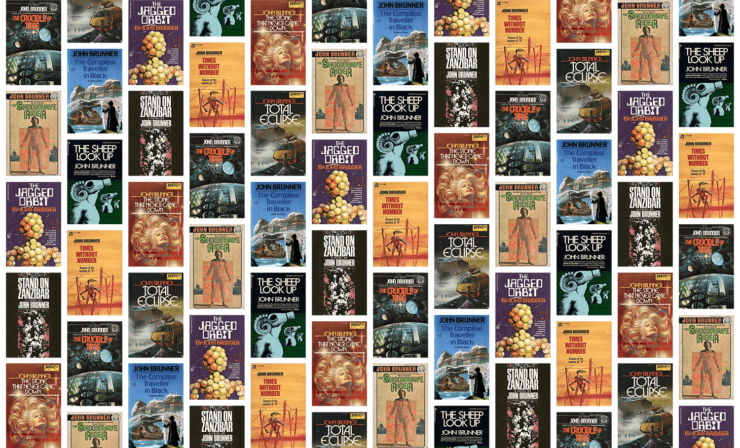

The Club of Rome Quartet

The books in Brunner’s Club of Rome Quartet are standalone novels unified by two premises. The first is that Brunner took for inspiration a different pressing concern of the day, building each book around the dystopian effects that could ensue should these social problems continue to worsen. The second is that the books were stylistically ambitious, a creative choice that brought Brunner critical accolades but, alas, no additional income. Nevertheless, they are arguably his best works. The quartet comprises the following four classics: Stand on Zanzibar, The Jagged Orbit, The Sheep Look Up, and The Shockwave Rider.

Stand on Zanzibar (1968)

By 2010, seven billion humans call Earth home. Such unthinkable overpopulation has widespread consequences, from ubiquitous eugenic laws6, to spiraling violence, all explored in Brunner’s lengthy, dense mosaic novel. A seemingly minor African nation may offer the world an unforeseen method by which overcrowding could become tolerable and sustainable; however, this gift has disturbing consequences.

The Jagged Orbit (1969)

Faced with the need to provide shareholders with ever increasing profits, the weapons companies of tomorrow, in particular the Gottschalk cartel, have done the only responsible thing they could do, which is to exacerbate political and racial tensions in the US. Seeing their neighbours only as potential enemies, Americans have armed themselves with a panoply of advanced weaponry. Still, some members of the cartel are certain that greater profits are to be had; their bold initiatives will bear a very unexpected harvest.

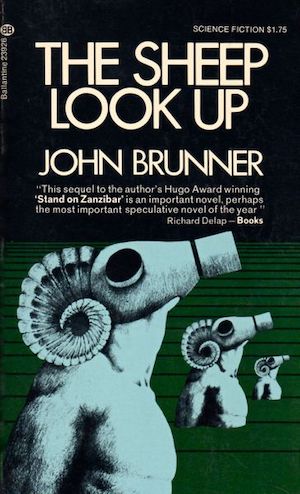

The Sheep Look Up (1972)

Prosperity demands sacrifice. As Americans become ever wealthier (at least on average), their environment becomes ever more polluted, continental ecosystems ever more fragile. This state of affairs offers yet more commercial opportunity: corporations can sell products that offer ways to survive increasingly toxic air and water (or so they claim). Environmental alarmists are dismissed as prosperity-hating nutcases.

The alarmists are correct. What had been slow decline is transformed into an accelerating collapse, just in time for America’s final Christmas.

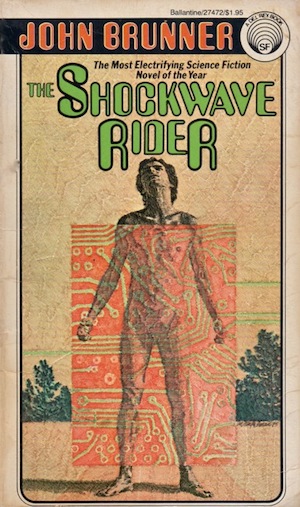

The Shockwave Rider (1975)

By the early 21st century, accelerating change and information overload are not merely a fact of life, but an increasingly disorienting, increasingly terrifying curse. Most people rely on drugs and therapy to cope, but these methods are curiously ineffective. It is almost as though keeping the populace dazed and confused is a deliberate decision. Nick Haflinger has a unique set of skills by which he can adapt to the world around him… but even his protean talents have their limits.

***

Brunner wrote many books. No, even more books than that! Thus it is absolutely certain that the ten books I selected are not the favourite Brunner books of many Brunner fans. Feel free to mention the books you prefer in the comments, which are, as ever, below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021 and 2022 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Some of you are going to say “1951…and he was born in 1934? That can’t be correct!” It is; Brunner got his professional start very young.

[2]He had to be prolific, because to make a living at SF he had to write eight and sell six novels per year. The creative constraints this placed on him were a recurring source of frustration for Brunner. According to Jad Smith’s monograph, the conflict between personal and professional goals contributed to Brunner’s death: faced with creativity-limiting side-effects from blood-pressure medication, Brunner went off the medication to focus on work in progress and died soon after.

[3]I’d love to include 1988’s The Best of John Brunner here, but I’ve never seen a copy and at the prices it commands on Abebooks, I doubt I ever will.

[4]In other hands, losing the ability to kid oneself would be the stuff of horrors.

[5]What about informed consent, you ask? Sadly, word count limits do not allow unpacking this.

[6]To be fair, eugenic laws were pretty ubiquitous when the novel was written—and unfortunately, they did not subsequently become as unfashionable as people might like to think they did.

The Shockwave Rider introduced the concept of a computer worm. Brunner was extraordinarily prescient. You have to not nit-pick on the details, because there was no way he was going to predict those perfectly. But the really important things, the trends, the driving forces, the big problems, he tended to get right.

I’ve read 6 of these ten. I’m behind on The Stone That Never Came Down, The Sheep Look Up, The Compleat Traveller in Black, and Times without Number.

My favorite three other than these ten follow. Interestingly, they all have upbeat endings.

– Catch a Falling Star (aka The 100th Millennium) — The positive ending comes after a travelogue through an enormous amount of decayed civilization. An astronomer discovers that a star is on a collision course with our solar system, and begins a quest to try to stop it. This was my very first Brunner.

– The Infinitive of Go — Teleportation is discovered, but you don’t quite get where you expect to go. The upbeat is that there are great places to arrive.

– The Webs of Everywhere — Again there is teleportation, but this time the focus is on the social effects. Luckily, the viewpoint scumbag character fails to achieve his perfidy.

It is nice to see ‘Times Without Number’ get some love. It’s the rare science fiction novel that provides a satisfying answer to the question: If time travel is possible, then where are all the time travelers?

Brunner was a mainstay of my youth. Stand on Zanzibar and Sheep Look Up transformed world. Thanks for introducing this extraordinary writer to a whole new audience.

I have very fond memories of Crucible of Time, I read it over and over when I was a kid.

I haven’t actually read any of his works yet, but I have a copy of Stand on Zanzibar on my tbr.

Between the length and subject matter, I’m still waiting for the right mood to strike to start it.

I’m quite fond of The Traveller in Black. Part of the premise is that the Traveller must grant the first wish he hears from any person, but is free to choose the interpretation, and always chooses a version which increases the amount of Order in the world. (Sometimes, that involves little more than something nasty happening to a very confused, foolish, chaotic person.) He may grant a second wish, which can undo at least some of the bad consequences of the first one, again in a fashion which creates more Order. There’s a passage which I, an experimental cook, find particularly appealing:

I remember that I read Stand on Zanzibar when I was in high school, and not liking it because I found it confusing. I don’t remember anything more about it, and I probably ought to give it another try.

I, too, have The Crucible of Time on my favorites list and am always pleased when it gets notice.

I’ve read 3 of the 4 “Club of Rome” novels – “Shockwave Rider” is positively jolly compared with Stand and Sheep. “Total Eclipse” is just dark on a dark background, while “Infinitive of Go” (as @2 says) ends on a positive note.

I absolutely love his Telepathist / The Whole Man. Cataleptic Telepathy is a good forerunner of VR.

Joel@7: You should definitely give it another try.

I don’t know if I’d include it as one of his 10 best, but The Squares of the City is interesting. The plot is structured around an actual famous world championship chess game (Steinitz vs. Chigorin, 1892). It was nominated for the Hugo in 1966.

Glad to see some love for the Traveller in Black stories. I wish there were more of them.

Complements for including Total Eclipse!

Total Eclipse was my first Brunner novel, when I was about 15, and I was rather surprised how much I could enjoy something so bleak, much different from most of my reading then. (Of course, I had been prepared by shorts like “Elected Silence” and “Easy Way Out”.)

My first in English was, I think, Catch a Falling Star, followed by Web of Everywhere (today I learned that The Webs of Everywhere is the vt of a 1983 US reissue). I remember very little, but I think I thought that one aspect of the future society was intended as a metaphor of fandom. I should take a look at it again…

I started with Shockwave Rider in my teens. Wanted to reread it, but forgot the title, and consequently read about half of these before I found it again. I’ve never met a Brunner novel I didn’t like.

And then there’s “Quicksand”. Is the dystopia described at the end real, or just the heroine’s delusion? We never find out.

Kudos for mentioning Times Without Number, which I read a while after Poul Anderson’s first Time Patrol collection – it wouldn’t surprise me if Brunner wrote the stories as a reaction to Anderson, since he covers some of the same ground but effectively puts the boot in to the idea of a stable time-travelling civilisation. Also The Traveller in Black, which is an excellent fantasy series for that era.

@10 – another vote for Telepathist, which I think was my introduction to Brunner, the City of the Tiger part was probably one of the things that led to my interest in role playing games.

Two that I enjoyed

The Long Result, a novel I read just after Telepathist which is an interesting look at a government department that does its job well, the job being alien contact. In fact the government depicted is so rational and works so well that I can’t help classing it as fantasy…

Timescoop, a fun romp about very rich people snatching perfect duplicates of anything they like, including people, from the past. Surprisingly, it more or less ends well, with only one of the scooped people killed because he’s completely out of his depth.

The Shockwave Rider holds an excellent claim to be the first cyberpunk novel (if you dispute Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), and both Stand on Zanzibar and The Sheep Look Up employ other cyberpunk-ish themes.

Brunner is hugely underrated and hugely underread.

Here’s a plug for Jad Smith’s monograph — I’ve been a Brunner fan for 50 years, and learned so much about him and his work just this year, from this thoughtful and well-researched book. I recommend this for everyone who’s discovered that Brunner was asking all of the best questions. (Think of Web of Everywhere as a novel about Jeffrey Epstein in a transporter machine.)

For Joel@7: I only completed Stand on Zanzibar only on my 3rd attempt, 2 years after first picking it up. Give it as good a start as you can, put it down when you’ve had enough… and let it stew in your brain for months, until you’re ready again. Eventually, it will mold you, and finishing it will be easy.

As another example of Brunner’s wide-ranging explorations in where SF could go, I recommend 1984’s The Tides of Time. Here, he ventures into what I think of as Le Guin’s turf: how much is our reality determined by the narratives we are able to construct about it? (And in that way, a thematic sibling to Quicksand.) I also wish I knew the fly-on-the-wall story behind the 1st-edition paperback cover, a lovely reference to the Club of Rome quartet by way of Thomas Cole’s 19th-century “Course of Empire” paintings.

I would recommend ‘Interstellar Empire’ – a 1976 fix-up of 1950s novellas about the decline and fall of the galactic empire. Quite Foundationesque. And ‘Victims of the Nova’ trilogy.

Having just reread Shockwave Rider I am curious as to why so many of Brunner’s works are set in the US. He was British after all. And he really does deserve to be better known.

I read The Sheep Look Up, Stand on Zanzibar and Bug Jack Barron (Norman Spinrad) at about the same time. I still find the accuracy of prediction in them remarkable.

I recently re-read Stand on Zanzibar having last read it 50 years ago. Stylistically it was revolutionary for its time, at least within SF. Even today, its format is unusual, and very effective. It definitely is a Brit’s take on the US. For example, how he depicts race relationships is a caricature. On the other hand, that this issue was even being highlighted in SF in the 60s was unusual. While some of the predictions are dated, others are amazingly prescient (see – muckers). All in all, it holds up quite well.

@10/@18: a third vote for Telepathist — another work that denies the claim that Brunner was always pessimistic, but with an earned ending rather than arbitrary cotton candy like many happy endings.

@0: I’m surprised at including The Shockwave Rider in the Club of Rome group; the US is run maliciously but not disastrously, and the rest of the world appears to be getting on better. I’ve always paired it with The Stone that Never Came Down as showing two cultures’ radically different solutions to a problem: the English are given a bit of luck and get on with it, while the USians rely on a [super]hero.

His trilogy of swinging-London works (The Gaudy Shadows, Black Is the Color, The Productions of Time) are not major, but still interesting; he mentioned in a GoH speech (Lunacon 1991) being influenced by all that was going on (at least on the surface) of late-1960’s London.

A Planet of Your Own is an edge case for the topic, since AFAIK it came out only as half of an Ace Double, not as a separate book. He was clearly still learning to write (especially when to stop writing — I wonder if he had to pad this to an arbitrary length), but according to a friend who was building a bibliography decades ago this was the first ~novel of genre science fiction in which a woman was the indisputable lead character. Fantasy had Jirel of Joiry (and IIRC in shorter lengths) some years earlier, and there were older didactic novels (e.g., Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland), but from what we could find this was the earliest female lead in a work published as acknowledged science fiction, at a time when it was still seen as a male playground.

I met Brunner just before his death (he was helping his 2nd wife set up a dealers’ table at Intersection); I had remembered him from 20 years before as having a ruddy complexion, and didn’t know he was dealing with medical issues — let alone that he’d been deviled by the same choice as Kornbluth 4 decades before. (Kornbluth at least had a 9-to-5 job to support his family.) I wonder whether the pharmaceutical tech has improved since then.

A lot of good choices here. One of Brunner’s short stories that I still think about is “The Totally Rich” (1964), wherein the ultra-rich (the 1% of the 1%) have such vast resources available to them that they can essentially create their own reality… or a reality meant to deceive and manipulate ordinary people. (It’s kind of a predecessor in theme to his 1966 novel THE SQUARES OF THE CITY, with its similar deception and manipulation of characters.)

A sadder chapter in Brunner’s career was his historical novel THE GREAT STEAMBOAT RACE. As I recall, Brunner took two years off his SF writing schedule to research and write something that was supposed to be his breakout book, something to put him on bestseller lists, something that would gain Hollywood’s attention, something that would relieve him from the grind of having to turn out SF book after SF book on a strenuous schedule.

Alas, the gamble did not work out for him. TGSR did not do well either in sales or in reviews. The Kirkus review notes the slow buildup in the first third of the book (not the only review to mention it), plus a very large number of characters to keep track of. When I read the book myself, there were some definite slogs involved. I enjoyed it, and would say it’s a “good” historical novel (especially if you’re a steamboat-era fan), but it’s not a “great” historical novel… and Brunner needed it to be great.

Brunner’s forte’ lay in the SF field (and in fantasy; THE TRAVELLER IN BLACK is one of my favorites), in his speculation and forecasting of trends and society into the future. For THE GREAT STEAMBOAT RACE, he put that talent aside, to the detriment of his career.

A particular favorite of mine is The Stardroppers, mostly because of the wonderfully evocative descriptions of the sounds heard listening to the stardropper. Add to that a tilted approach to spycraft and it’s just a lot of fun. It’s not prescient like The Shockwave Rider (and boy, did that one astound me when I read it in 1975!), or a “major novel” like Stand on Zanzibar, but it’s likeable, and pretty positive for Brunner.

Found Best of John Brunner on Half Price books for $1.99. Just sayin.

I’m glad to see Brunner get some love, as I’ve always thought that Brunner was one of the best, and better than a lot of the more well-known names.

The last few pages of The Sheep Look Up has stayed with me forever since I read it in the seventies, and I loved The Stone That Never Came Down. It sits in my head next to Quatermass.

I discovered Stand on Zanzibar in the late 70s, just before entering the Navy. I was blown away. Brunner’s method (which I believe he called the Ennis Mode) reminded me of Joyce’s Ulysses, but with for more order and compartmentalization. In addition to the main plot, Brunner provided three levels of perception that clearly outlined and sculpted the world of his 2010. I have always been amazed at how few novels I have seen follow that example.

A couple years later, I read The Sheep Look Up while attending the USN Nuclear Power school in Orlando. The latter novel was written in a mode similar to the former, but with slightly less structure—a kind of controlled chaos reminiscent of stream-of-consciousness but (as with Stand) more structured and lucid. Again, the mode provided a depth of immersion that would have taken five hundred words in standard narrative form.

In comparison with Stand and Sheep, I found Shockwave Rider to be bland and disappointing (pace, Brunner stalwarts: only in comparison with the other two works). I know Mr Brunner had to publish a crushing number of novels just to keep his head above water, and I’ve often wondered if that’s why he had to abandon the Ennis mode. It was, no doubt, quite taxing to write on so many levels at once. I find it truly tragic that those two works did not receive, while the author was still alive, the literary attention I feel were their due.

I’ve never read anything by Brunner that at minimum wasn’t good, and most of it I think is great. What I especially like is that, even in his early works, he never seems to take the premises in a standard direction for sci fi of the time. Science fiction seemed to grow in his direction, much like Alfred Bester.

I’ve got a copy of his first collection, No Future in It. Every story in it is great. The Dramaturges of Yan is a great, spritely novel about a human outpost on an alien world, where the setting is great, and the plot goes in all kinds of interesting directions. I really like the novella No Other Gods But Me (also called A Time to Rend), which really shows how he is able to take a genre concept (magic powers, basically) and turn the outcomes on their head in a most illuminating way. Out Of the Slave Nebula does the same thing with … well, interspecies slavery.

I’ve got Times Without Number sat on my shelf, so I’m glad to see it endorsed here. And all his famous later novels are all great (still waiting to find a nice copy of The Sheep Look Up, but I hardly think I’m going to not like it at this stage). But what I am trying to say is that he was top notch from his earliest work, and shorter stuff including shorter novels and novellas.

Don’t think anyone has mentioned yet either that he was one of the earliest authors, much like Clarke (in Rendevous with Rama), Delany (in Babel 17) and others, to very deliberately often give his lead characters backgrounds and names from all over the globe, and not just America and the UK.

Also found his best of collection for less than $10. Some of the online sellers see out of print and mark things up beyond their ability to sell them because the demand for the titles doesn’t actually justify the price.