Last week I went to see a band, which is a fairly normal occurrence for me. It wasn’t just any show, though; it was a date on a 30th anniversary tour, a celebration of a record that came out decades ago.

It did not feel particularly celebratory. But it did feel specific. The Lemonheads’ It’s a Shame About Ray is an album from the early ’90s, made at that specific time, riddled—to those who listened to it both then and now—with potholes of nostalgia, splashes of memory. I can’t hear it without hearing the echoes of when I first heard it.

But it’s not timeless. I’m not sure music can be timeless; it’s ephemeral and visceral at once, subject to the recording tools of its day, bent and shaped by so many forces and talents and skills and feelings that it almost can’t not be of a moment.

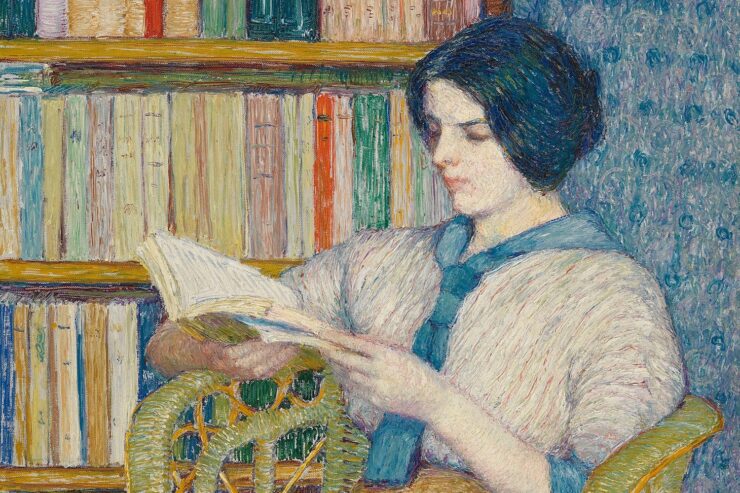

Can the same be said of books?

Every so often, an argument about “timelessness” crops up online; someone was shouting on Twitter recently about how nothing current, on the literary front, was going to last. My primary response to this is always the same: Why does it matter? We’re reading now. We’re not reading for later. Later can make up its own mind.

There is absolutely no telling what stories will last through the ages and which won’t. Any reader of classic literature can tell you all about the many now-classic writers who went ignored or underappreciated in their lifetimes. There are countless books written in previous decades and centuries that 99% of us, now, have never heard of. (I’m allowing a percent for the scholars and researchers and obsessives who might want to tell me I’m wrong.) There are also countless former bestsellers or award winners whose names we no longer recognize.

But there is something about books that seems to invoke a question of timelessness, of lasting, of echoing down through generations. Maybe it’s just that we’ve had printed books longer than we’ve had easily accessible recorded music. Maybe it’s the aesthetic of leather-bound old books, which lends them a sometimes unearned weight, as if the design itself makes them important. Maybe it’s the knowledge of the sheer amount of time that goes into writing a book—weeks in rare cases; months frequently; years, often. Maybe it’s that it takes longer to read a book than it does to listen to a song or album.

“Timelessness” is, of course, impossible. Every story is of its era, whether we perceive all the things that make it so or not. Anyone who’s not a straight white man and has read a classic is likely deeply aware of the lie of timelessness: the people who were not considered people, the rights that were not considered inalienable. When we say “timeless” we often mean “still considered relevant.” I say considered because this might not remain the case. Books fall from and join the canon all the time. “The canon” itself is an illusion: there is no one singular canon. It’s word of mouth and general consensus on a large and educational scale.

I don’t say any of this to dismiss classics, which show us where we’ve been and where we’re still going, which are still in conversation with the present, with the living writers we love, with the paths so many have walked to bring us to where we are. But overvaluing a perceived timelessness devalues the beautiful, peculiar, fascinating ways that a book can be of a moment. Of an era. A book can be a snapshot, a snowglobe, a bell jar. (Many, if not all, classics certainly have this quality too, but as I am not deeply informed about every era of history, I can neither confirm nor deny.)

Blake Nelson’s Girl is a precisely faded Polaroid that captures what it felt like to grow up white and grungy in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1990s. It’s historical fiction, now, and probably not relatable to modern teens, but that doesn’t change what it is, just how it’s read. Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell and David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas were both published in 2000; both novels set their stories in different eras, but both also feel of a moment when literary fiction was expanding, breathing in, taking big gulps of fantasy and strangeness. The books that shaped so much of a certain kind of SFF—the cyberpunk stories and their immediate descendants, your Neuromancer and your Snow Crash—those books had to happen when they happened. They are classics now, though not at all timeless. But as the years march on, it may be some other novels altogether that tell the story of how we imagined the internet, once upon a time.

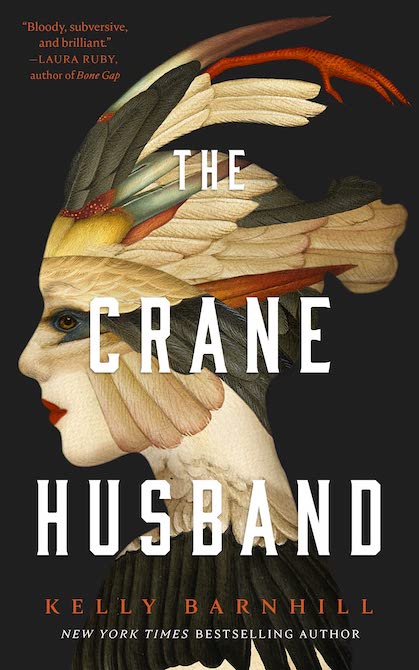

Buy the Book

The Crane Husband

Tolkien may have wanted to create a timeless myth of England—something outside time. Fantasy loves to put its roots down in that outside-time zone, but the work itself is still of its time. Everything is of its time. There are reams of YA dystopias from the late 2000s that are so incredibly of their time that some of them now feel almost like they came from a different planet—and some remain sly and wise in their era-specific-ness. Much of the coming-of-age fantasy I read as a kid might have come through the wringer entirely differently in the last ten years; some of those novels might have been published as YA, or might never have been published at all. The stately pace of something like The Copper Crown is astonishing to look back on—as are the regressive gender roles in a whole lot of ’90s fantasies that it’s probably best for me not to name.

All of these things were steps on a path. In many cases one might wish we walked the path a bit more quickly, but here we are, reading books that may, a few years down the road, seem very of a moment we can hardly see while we’re in it. That moment isn’t always something big in the outside world—it can be a personal moment, a rough patch or highlight, a phase when you were reading only a specific type of book (why did I read every YA dystopia published in the late 2000s!). Or it can be the moment when we were all indoors, waiting for science to catch up to a virus, feeling disconnected or afraid or alone. That moment won’t just manifest in brilliant and overtly pandemic-focused novels. It will show up in other forms—in what we read and wrote, how we read and wrote it, and how people respond to the art of that time and its long shadow. Some of it will last. Some of it will be forgotten.

What happens when you read a book is not the same as what happens when a country, a class, a demographic, a generation, a subculture reads a book. The two things can and do inform each other, but the singular and collective experiences are wildly different. Somewhere, between the two, might be where classics are born—where things seem to step out of time, leaping from their eras to ours, resonant and true. But classic-ness isn’t necessary. Meet a book where it came from, or reject it on those same grounds. It only has to be what it is. It only has to exist when it exists. What it’s going to be is entirely unpredictable. What is for you, now, is entirely up to you.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.

Some books, songs, etc., are ephemeral bits of a specific time, only remembered because of the personal memory attached, but others will continue on for a very long time. The songs we now call pop standards can be over a hundred years old, but they still resonate for their emotions and musicality. Modern singers, even rock stars, seem to gravitate toward these songs. Rod Stewart has 3 pop standards albums.

On this site, there are always articles about the older books and authors, and it’s not just us fossils who remember them and read them. If a song or book touches us as an individual or as a people, they will always will remain a classic.

The future gets to decide what’s “timeless” (for given values of timeless, as you specify, Molly).

Having said that, the original impetus for the article is what I want to talk about. Based on the subtext of your Twitter rant comment, I’m guessing original Twit-er was a critic (self-appointed or otherwise) who was fundamentally mad that someone or -ones, was not reading some set of “classics” that he, she, or they wanted them to be.

It has become genuinely EXHAUSTING, in the age of social media, to deal with all the people who think that other people (I can only speak for myself and my family, but all three of us are of like minds) should just like the “right” things, spend money on the “right” things, and speak about the “right” things. I don’t even care at this point, whether I agree with them about “right”…it’s just exhausting dealing with self-appointed curators of the human experience in every single facet: books, film, music, politics, games, social activities.

And, yes, in THEORY one can create filters and install front ends to filter out the endless stream of moral scolds (of whatever stripe) but you’re only one update away from having to do it all over again. Exhausting.

I don’t know how to solve it unless someone figures out a way to add a “STFU You Pretentious Scold” emoji. And even then, let’s be honest, the assholes are more dedicated to being assholes than the rest of us are to a philosophy of “de gustibus non est disputandum”, and they have more ways than ever of inflicting their mania on us. Maybe that’s what ails us all now. But I’ve decided to take a page from Reddit (a site LOADED with examples of what I’m saying) and respond YTA.

I think GOOD OMENS has a chance to be timeless.

Sure, as you say “the work itself is still of its time”, but sometimes it just catches an immortal glimpse of humanity’s real impetus (or hubris) and lasts forever. Cicero was thinking about his enemies while he was writing De re publica, yet he captured the purest essence of democracy in his words. I would count 100 to 150 eternal books as of today

@3 You’re right, and it would be heavily ironic, since that book has so many late 80’s- 90’s references, like cassette tapes,or Crowley’s answering machine in terms of technology. However, it is a story that could be told in any time period, if you take out said references. There are other stories too, like To Kill a Mockingbird or Of Mice and Men, where they are set in specific time periods but so encapulate the era that they become a stepping stone to understand that era. I think that’s what we mean by Timeless, it’s something that you understand immediately, no matter when it was written

@5 Steven Hedge

I wouldn’t be too sure about that. One of the minor plot points was that Pestilence retired in favour of Pollution, but if these last few years have taught us anything it’s that Pestilence is putting together one hell of a comeback tour. Personally, I find it to be very much a “of its time” book. “Classic”, yes, but not timeless.

Books are written and then edited by people (at this point in time, at least) and people are molded by the time they live in, even if they do seem wildly ahead of their time. Even things like pacing, descriptions and ideas about humanity (because it is the rare book that doesn’t touch in some way on humanity) are shaped by time. The editorial standards of today may not be the editorial standards of the future. And that alone will prevent a book from being timeless.

I like books that aren’t of their time- example Samuel R. Delany’s Babel-17. It does not read like a book from 1968. It could have been published yesterday.

Concerning Good Omens, I think that it bears the clear imprimatur of the time in which it was written, and not just in terms of answering machines or Queen cassette tapes. It’s a fantasy of the end of the Cold War, and its entire world is framed in a Cold War idiom. Aziraphale and Crowley are basically a celestial enemies-to-lovers fanfic of Spy Vs. Spy.

But of course, everything is a product of its time. So the question isn’t really about books themselves, but about their resonance. Can a book be written in such a way that humans in general, beyond those living in a certain time period, can find meaning it in? I think the answer must be “Yes,” given that people are still reading things like Journey to the West or the Iliad. As for more recent books, I could easily imagine that, in 500 years, every English department will have at least one specialist in Pratchett Studies. Assuming that there are humans then.

Silverlock, by John Myers Myers. And “Who Fears The Devil”, Manly Wade Wellman.

For British, the Jorkens stories by Lord Dunsany, and Tales From The White Hart, by Arthur C. Clarke.

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice originally published in 1813

I don’t mind that things are of their time because we are creatures of time. But there certainly are stories that are so well written that they transcend that.

It’s the same with music. My biggest association with the pandemic has actually been music, and I’m also following a weekly feature that goes through the Billboard hits (starting with 1958 – it’s up to 2004 now) and that is definitely an interesting look at what music stood the test of time – there’s the stuff you might expect (the Beatles, The Supremes, Cher, Britney, Whitney Houston, Usher, Michael Jackson, Beyonce, Mariah Carey, Madonna, etc) but there’s quite a bit that I have literally never heard of…not to mention several songs/artists that never even made it even though they are still well regarded today. But almost all of those songs have a story of how and why they ended up number one when they did.

I’d figure Titus Groan and Gormenghast are not tied to the time they were written.

I love Cory Doctorov’s novels. They sure are of our time right now, and may seem a lot less relevant in just a few years. Nonetheless, right now I learned a lot from them I was not aware of or see it from a different angle.

That they may be less relevant or understandable in the future does in no way reduce their current value for the reader. Rather it is what makes them so strikingly unsettling and evocative for me.

Interesting. What elevates a work (or works) of art to a ‘timeless’ level?

Take the Star Trek franchise. Each iteration is most definitely a product of its time (TOS is so very 60s, early TNG so very 80s, etc.), but taken as a whole the Star Trek franchise transcends the times in which it was made–it has attached itself onto the cultural consciousness far beyond other, similiar intellectual properties. Why?

Now to switch tacks, take the Beatles. Each of their albums is an evolution informed by the time and environment in which they were made. A Hard Day’s Night is a product of 1964 as much as Sgt. Pepper is a product of 1967. But taken as a whole, the band’s discography is more than just classic rock or whatnot. It has impressed itself on our culture in a way other, similar musical acts have not. Again, why?

There is an ineffable quality to what constitutes a timeless work of art, in my opinion. It’s akin to something being greater than the sum of its parts. Quality of the work, its social impact, its influence on other works of art–all important. But there is something almost unexplainable about what makes a work of art transcend its time. It just happens.

Personally, I think there are timeless themes but no timeless books. This is because although the story may be timeless in essence, it is still written by a person in the context of a specific time, a temporal culture you could say. And like all cross-cultural communication, there has to be some common language. Which further means that if cultures drift far enough (as they do across time), any book will eventually become incomprehensible to society, even if the story itself is still relatable.

That’s more technical logic, though, that doesn’t really get at the spirit of the question. To the question of whether any book can be timeless, first I would agree with Molly that I’m more concerned with what I’m reading here and now and second, that it seems to be conflating timelessness with value. I posit that a timeless book is just a book that is enjoyed by a lot of people, and we assume that if a lot of people like something, it’s probably good. This doesn’t prove that the converse is true, that if only a few people enjoy something, it’s bad and worthless. I think that if a book benefits even one person, that gives it value. Given the vast historica of literature, lists of classics have their place in giving new readers a starting point of likely books to try, but really, the main benefits of a “timeless” books is that if a lot of people enjoy it, random odds mean you have a better chance of enjoying it and if you do, you have a lot of like-minded people to rave with.

It is an odd thing.

Some books are so ephemeral they’re barely “of” the time when they were written, let alone any other.

And some books you would think ought to be ephemeral as all get out, and yet people still read them long after. I mean, take P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster stories. OK, so, silly comedy with no message or satire or anything. About a guy from a very particular kind of “idle rich” class, and his butler of all things. Full of cultural references that are totally about the fluffiest, most forgettable parts of the early 20th century. They should have no staying power or ongoing relevance whatsoever. And yet, they’re still so damn funny.

It is true that even works often considered “eternal” still usually require that you wrap your head around the time they are from, at least a bit. Take Hamlet. Massive classic and all that, but the high school kids that get it shoved down their throats mostly don’t get it at all. The human issues are kinda timeless, but a lot of people haven’t thought enough about how modern power struggles, like say in high school cliques or modern party politics, map onto medieval/renaissance dynastic infighting, to be able to get the underlying similarities. And lots of people don’t have enough flexibility in how they deal with language to handle the archaic stuff, both the actual language and the poetic cadence. So in real life, it’s not that accessible to most modern people–their actual experience of it is that it’s something very much of its time and alien to them. And yet . . . personally, I actually rather like Hamlet, and I do feel there’s stuff in it that can speak to a modern person who’s willing to meet it halfway.

@16 @14 “You have not experienced Shakespeare until you have read him in the original Klingon.”

*swoon*

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell

I’m always so excited to see any mention of Susanna Clarke’s amazing tome. Interestingly her recent release Piranesi could be fairly timeless as we move into the future. Obscurity and random intrigue tends to lend itself to wide interpretations and opportunities for many generations to benefit from.