Having complained about one particular aspect of science fiction and fantasy settings for decades, it belatedly occurred to me to start tabulating data1 to see if in fact there were any support for my impressions. Going on gut feelings is, after all, how I got stabbed with semi-molten glass.2

And what, you ask, was the aspect being tracked? Try not to get too excited when I say it was “type of government depicted.” Are science fiction and fantasy as rife with autocracies as some have implied? Or is this merely an illusion, one to which I might be subject because I am personally rather tired of autocratic settings?

It’s been nearly a year since my project began. The results are not quite as I expected.

Methodology

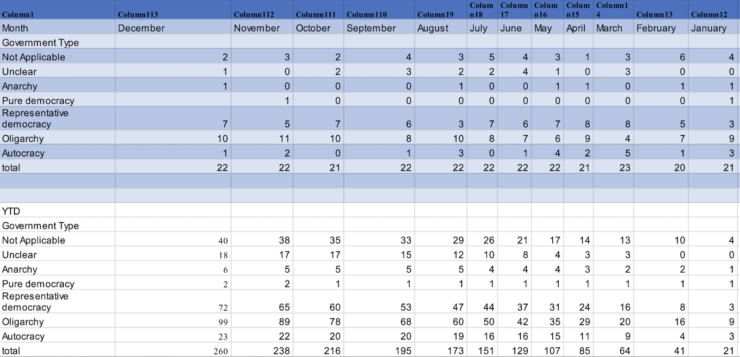

I was torn between curiosity and sloth. Did I want to sample all SFF? If focusing on a representative sample, how would that be chosen? In the end, sloth won: I surveyed a subset of the reviews I have been posting on my personal website (James Nicoll Reviews). I’ve been posting since 2014; at the time I write this my site hosts 2268 reviews. A good sample but… I didn’t start collecting and posting stats re: government type until 2022. Sample size much smaller (260 reviews), but easy to tabulate, because I compiled stats at the end of each month. Adding up the monthly totals was simple.

The categories I assigned each work:

- Not applicable: anthologies, non-fiction texts, and other works that lack a single setting.3

- Unclear: works where I could not figure out how government functions.

- Anarchy: works with no functioning governments.

- Pure democracy: works where all inhabitants have a say in communal decisions.

- Representative democracy: works where people select representatives to make decisions on their behalf.

- Oligarchy: works where a small group of people govern without meaningful input from the populace.

- Autocracy: works where a single person governs without meaningful input from the populace.

Works are categorized using the time-honored “I know it when I see it” system.

Disclaimers

The data set is not huge, although at more than 200 works I should see some real trends.

My categories are somewhat idiosyncratic, selected because sorting books into a limited number of sets is a lot easier than a more complicated array would be. (I cannot emphasize strongly enough how bone lazy I am.)

Bias cannot be ruled out, since I select many (but not all) of the works I review. Knowing something about the work beforehand may tempt me to pass over a story I suspect I would dislike. Balancing that, my patrons select many of the works reviewed4, so the results are not entirely shaped by my personal tastes.

Results (as of December 31, 2022)

Government Types (books read in December): Total 22.

- Not applicable 3 (14%)

- Unclear 0 (0%)

- Anarchy 0 (0%)

- Pure democracy 1 (5%)

- Representative democracy 5 (23%)

- Oligarchy 11 (50%)

- Autocracy 23 (9%)

Government types (books read in 2022): Total 260.

- Not applicable 40 (16%)

- Unclear 18 (8%)

- Anarchy 6 (2%)

- Pure democracy 2 (0.5%)

- Representative democracy 72 (28%)

- Oligarchy 99 (36%)

- Autocracy 23 (9%)

Discarding Not applicable and Unclear, and sorting by frequency for books read so far this year:

- Oligarchy 99 (49%)

- Representative democracy 72 (36%)

- Autocracy 23 (11%)

- Anarchy 6 (3%)

- Pure democracy 2 (1%)

…This was a surprise. Yes, Oligarchy is in the lead but Representative democracy puts in a respectable second-place showing. Autocracy, seemingly so prevalent that certain persons have complained about how often it comes up, is only a distant third.

What could explain these results? A few things.

A. A surprising number of SFF works are set in contemporary Western societies and at the moment, a lot of those are representative democracies. Granted, some are more convincingly representative democracies than are other societies, but my categories are forgiving.

B. There’s a tendency for people to write what they know, even when they are setting works in the future or in a fantastical realm. This is especially the case if government isn’t the focus of the work. Adopting a familiar setting is easier than imagining a plausible but novel setting.

C. Anarchy and pure democracy may be disadvantaged by the fact that at this time, such governments are rare. Not only that, they are not currently being promoted or discussed with the fervor often shown in the 1960s and 1970s. If libertarians are mentioned these days, it seems to be mostly in the context of developments like bears overrunning a libertarian community. The wheel could turn. We could see more novels like The Probability Broach and Alongside Night at some point…but the wheel hasn’t turned yet.

D. Practicality. Rulers may decree that “I am the state” (l’État, c’est moi) but they would have a hard time implementing their orders if there weren’t a state apparatus to do that. But as soon as there are underlings or bureaucrats, those folks may use their position to sway policy. They can interpret orders from the top to suit their own beliefs or interests, or lackadaisically enforce orders they don’t like. There will be nepotism. Autocracies usually turn into oligarchies.

E. Oligarchies occupy a sweet spot from an authorial point of view. They are prone to faction, which makes for interesting plots. But there are few enough factions that it is easy to keep track of them all. Plus, leaders or prominent members of the factions can wield a lot of power, which helps generate plot and intrigue.

IMHO, these five factors appear sufficient to explain the results. Perhaps I am overlooking something? Feel free to explain what it is in comments, which are, as ever, below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021 and 2022 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]I honestly do not know why it took me this long. After all, the second thing I do in tabletop roleplaying, after generating a character, is to create a spreadsheet detailing all of the player characters’ stats and skills.

[2]I do not recommend contacting molten glass. Weird fact: I was the only person in my First Aid class to have experienced fourth degree burns.

[3]“But surely many short stories feature governments of one kind or another!” you proclaim. I cannot emphasize how lazy I am. Tackling short stories would increase my workload by an order of magnitude. That’s not going to happen.

[4]“Could your patrons ask you to review ‘The Number of the Beast’?” They could and I would grudgingly accept, but it would count as ten reviews. I’ve read “The Number of the Beast”—twice—and I can honestly say being on the receiving end of a brutal murder attempt was more enjoyable than reading “The Number of the Beast.”

I am also really surprised that “oligarchy” comes up so much – that certainly wouldn’t have been my impression. I think your E may be one reason.

Another may be that you’re perhaps throwing a lot of things into the “oligarchy” bucket that other people might class as “autocracy”, especially in view of your point D “But as soon as there are underlings or bureaucrats, those folks may use their position to sway policy. They can interpret orders from the top to suit their own beliefs or interests, or lackadaisically enforce orders they don’t like. There will be nepotism. Autocracies usually turn into oligarchies.”

I suspect that this would lead you to categorise something like Lois McMaster Bujold’s Empire of Barrayar as an oligarchy; after all, it has Counts who have considerable autonomy. But it’s still an empire with one guy in charge, and other people would definitely call that an autocracy!

My rule of thumb is “In supposed autocracies, do the rulers’ decrees determine actual policy?” Very often, it seems like the functionaries below the ruler get more say.

I will admit the fact I more often than not put books back down as soon as I encounter terms like “prince”, “princess”, “queen”, or “king” is skewing the outcome.

First random thought:

One might run a statistic like this and check if the society is protrayed with approval, disapproval, or a neutral viewpoint. Quite subjective, of course. But I’m reminded of the quip “adventure is someone else in deep trouble, preferrably far away or long ago.” Would SFF novels tend to attract settings where it isn’t all peachy?

Second random thought:

What you describe as pure democracy is often called direct democracy.I find that a better term. It also explains why it tends to break down at the large scale. (Call a planet to a townhall meeting? Yeah, sure.)

Third random thought:

Did you encounter and categorize rule by AI? I’m reminded of the Culture by Iain M. Banks, which is an autocracy whose organic inhabitants think they have pure democracy …

One of the ruled by AI settings was also a democracy: the humans in Bass’ Half-Past Human are malnourished and ignorant, but details in programming keeps their their robot minders from operating by decree. Despite being in a permanent brain fog, humans do get vote on important stuff.

(it’s not an ideal world to live in)

I am not surprised. SFF tends to follow the real life Golden Rule – he who has the gold makes the rule. Autocracts often rely on lesser autocracts for their power creating a feudalistic oligarchy. Representative Democracies only function as long as they don’t step on the oligarchs toes and are also most easily corrupted by the oligarchs’ gold.

This is such a nerdy thing to do and I love it :)

The relative frequency of oligarchy does not surprise me — in fact, I would have expected it to be higher, usually in the form of “meritocracy” or “rule by the competent,” seen in its most extreme form in “Galt’s Gulch” (Atlas Shrugged) but common enough, if only by implication, in “classic” SF.

Perhaps your selections of what-to-read may affect your results. Perhaps mine would affect mine if I did such a study.

What I am surprised by, however, is that you did not siphon off theocracy into its own category…

More articles like this, please!

I find the bolstering of opinion with fact to be quite a bit of fun. It feels like there’s suddenly more books about X or written by group Y. Is it true? Numbers can come to the rescue, show trends, etc.

Like you, I would have assumed autocracy at first – King so and so being pretty common in fantasy. But once I thought about it, I quickly came to the conclusion your numbers do – many more books both Fantasy and SF deal with guilds or other factions vying for control. Sometimes they are doing this without a monarch at the top. Other times a ____ among equals. (I forgot the first word) where the guilds elect a president of sorts as a tie-breaker. And there are stories like Dune where there’s an Emperor, but his state is precarious without balancing out the various nobles.

Many, many authors enjoy writing about the aristocracy and having plenty of money gives characters time enough to have adventures. Sadly, this leaves us with many interesting worlds that are desperately in need of a workers revolt and perhaps the invention of a nice, easy way to remove fancy heads from well dressed shoulders.

Seems a bit lazy not to include a spreadsheet of which works fell into each category, but I know you are not lazy…

:D

@9 & 10 – I worked out some time ago that I had a strong dislike of modern Fantasy – particularly High Fantasy – that assumes an aristocratic oligarchy or autocracy is the natural form of government. I can accept this in classic Fantasy, particularly where the author hails from a society where a residual aristocracy still exists in some form (eg, Britain), but I find it difficult to understand why 21st Century authors would consider such an a system to be fine and dandy. Of course in some cases (eg, “A Song of Ice and Fire”) Kings, Dukes and other assorted knobs are depicted as just as likely as the great unwashed to be thuggish, violent and stupid, but far too many still feature naturally wise, enlightened aristocrats and autocrats (along with their cartoonishly evil opposites). Where are the massive trilogies of four volumes or more that chronicle the transition of a Fantasy land from Kingdom or Empire to representative democracy?

What is the government type of a revolutionary movement? The wave function hasn’t collapsed yet, so we don’t know, particularly.

@12 I imagine Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn series is heading that way…

I’m reminded of the Culture by Iain M. Banks, which is an autocracy whose organic inhabitants think they have pure democracy

You’re maybe thinking of Neal Asher’s Polity? The Culture is canonically a direct democracy – the inhabitants vote on issues like “going to war with the Idirans”.

I worked out some time ago that I had a strong dislike of modern Fantasy – particularly High Fantasy – that assumes an aristocratic oligarchy or autocracy is the natural form of government.

I think there’s a distinction between “natural”, “possible”, “inevitable” and “desirable” here that would be worth exploring, as well as the distinction between “depiction” and “endorsement”. Big Man systems and their descendants are incredibly common across history and around the world.

@12 Perhaps surprisingly, one answer to your final question is … Discworld. The city of Ankh-Morpork is one of the few fantasy cities that sees massive modern development over the course of its books.

Actual socialist states were popular in scifi for a while, do they not get a category? Like the idealistic utopias of writers who grew up on star trek

some of those dont map cleanly onto direct democracy or oligarchy, many are run by benevolent AI or workers councils, and thats too much top down organising to be anarchy also

i suppose they could all slip into unclear

@mcannon

”Where are the massive trilogies of four volumes or more that chronicle the transition of a Fantasy land from Kingdom or Empire to representative democracy?”

because the fantasy enlightenment is much harder to write? You’d have to rewrite some of the great works of modern political thought that started the revolutions against monarchism, but tailored to the circumstances of your fantasy setting

orrrr you could just do the character work and political intrigue for a feudal setting, which while still difficult is easier to write than a believable fantasy enlightenment that doesn’t just seem like you are copying john lockes homework and making a fantasy not!marx

people, generally, do what is easier

and writers are people too

The science-fiction writer, Jerry Pournelle, once suggested that aristocracies had an advantage when it came to long-term planning, since they would be working on the basis that it would be their own descendants facing any future problems. That dedicated socialist, George Orwell, suggested that where membership of an organization – the Inner Party, for example – was by selection, then the people doing the selecting would tend to select candidates of the same type as themselves, reducing diversity, whereas when selection was by accident of birth, then the vagaries of upbringing, environment, education, and so on would increase diversity.

As Orwell pointed out, the eccentric aristocrat is a stock figure whereas the eccentric commissar is practically a contradiction in terms.

@19 That’s an oft-expressed theory, but in practice the observed stability and long term thinking in autocracies doesn’t seem to be that much to write home about.

Ditto bureaucratic party rule- the most prominent example when Orwell was writing collapsed half a century later, while the inefficient democratically ruled state full of eccentrics he was writing in keeps muddling along.

Orwell was very worried that the unity of purpose of totalitarian states would be an insurmountable challenge for fractious democracies, but events suggest that the latter weren’t as fragile, and the former weren’t so inexorable, as he (understandably!) feared in the wake of the previous two decades.

@16 Ankh-Morpork modernizes and develops more of a rule of law culture, but never really democratizes, presumably because Pratchett never really wanted to get rid of Vetinari.

It’s interesting to imagine what happens after Vetinari dies, though. Carrot probably spends a lot of effort *not* to be put in charge. Which might wind up with him pushing Vimes into the job.

Not as Patrician, and obviously not as King, but maybe at the head of some sort of guild council. Or who knows, maybe that is the point where someone proposes using an old legendary Ephebean method they read about where everyone marks a potsherd with their preferred choice. “I think they called it the Crackpot System.”

It’s interesting to imagine what happens after Vetinari dies, though. Carrot probably spends a lot of effort *not* to be put in charge. Which might wind up with him pushing Vimes into the job.

I don’t actually think Vimes was going to live much longer – not long enough to succeed the Patrician, anyway. There’s a line in Night Watch that caught my attention – Vimes is looking at a version of himself from another bit of the whole ball of timey wimey stuff (long explanation elided here for brevity) and says “how do I know you’re me and not just something pretending to be me?” and the other version of Vimes says “well, this is what you had for breakfast today, this is the last thing you said to Sybil this morning, and you’ve got this pain in your chest that you haven’t told anyone about”.

I think the cigars were going to catch up with Vimes in another few books, but the Embuggerance caught up with the author first.

@22: I’m also not sure Vimes and Vetinari were that different in age. Their younger selves seemed not far apart in age in Night Watch.

@12: “assumes an aristocratic oligarchy or autocracy is the natural form of government”. ‘natural’ is vague here. Historically, they _are_ the natural form of government for agricultural societies, particularly beyond the scale of city-states; you can’t even have an alternative at larger scale until the invention of representative democracy, quite late in history. ‘natural’ doesn’t mean _good_, mind you.

“the transition of a Fantasy land” — Liveship Traders is the only one I know if, and that’s just Bingtown going from merchant oligarchy to post-slave revolt democracy, or something like that.

@3: SF has had a few direct democracies: Joan Vinge’s Demarchists, explicitly voting; Alastair Reynolds’s Demarchists, implicitly voting via implant; arguably his Conjoiners, forming consensus via cuddly-Bog implants; the Culture, ostensibly.

There’s also different varieties. You can try for everyone having a literal equal say in discussion and deliberation; this breaks down quickly with scale. I presume even Athens, or New England town halls, don’t expect every one of up to 6000 attendees to speak. Or you can have a smaller body that proposes laws and/or budgets, but popular votes on those. Modern Switzerland is close to that: a fairly conventional elected legislature writes laws, but it’s pretty easy for a minority to bring such a law to referendum within a few months, so I imagine few unpopular laws stick around. No need to take to the streets in protest when you can just vote. One could extend that to the legislature merely proposing laws, which had to pass referendum to become laws. Representative or direct democracy?

The most famous science fiction story describing an anarchist society is probably Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. It offers a very different understanding of ‘anarchy’ than described here and is also an amazing novel in it’s own right.

1) It would be very interesting to see a similar table showing economic systems. For example, capitalist, socialist, communist, mercantilist, etc

2) I’d love to see the list of books this data came from.

@Flareonflare

Here is an example of a transition from an autocracy to, not a democracy, but a constitutional monarchy with rudimentary checks and balances: Mistborn by Brandon Sanderson, especially book 2. It does a good job of showing why it happens then and not some other time, as well as some of the challenges it faces, without going too deep into the theories behind it.

Modesitt’s third Imager series explicitly involves a conversion from the autocratic imperial setting of the second series to the representative council of the first, via the abdication of the ruler and the adoption of representation.

it’s not a true democracy mind you,the council is based on power sharing between the guilds, the nobles and the traders – the issue of the commoners getting representation is raised in the first series.

@0: ISTR that the world of The Probability Broach has not a pure democracy but a representative pseudo-democracy: if you show up in the assembly (in the Dakotas IIRC) you get a vote, or if you trust someone who has the time to spend in the middle of nowhere (where do these people get money to live on?) you can give them a sort of proxy, but otherwise you’re out of luck. The only check on this was that none of the assembly’s votes actually had an effect unless some fraction of the population was represented. It’s all slightly more plausible than his claim that trimetallism is a usable basis for an economy.

Also: have you read Kornbluth’s The Syndics? The framework is that official governments were driven out some generations ago (the US government is hanging on in Iceland and Ireland, with with local and continental-European slaves), leaving the east coast in the hands of an Italian-derived formerly-criminal and the midwest in the hands of a ~Irish one. Both resemble oligarchies, but the eastern one has more people who have to agree to any serious action, and kicks out offspring who don’t show competence.

A number of authors have argued that people under stress tend to look to anyone who seems a bit stronger or more competent, then have to live with the results; see (for variety) Paxson’s “Vai Dom” (about how the people of a crashed starship started the transition to Darkovan oligarchy) or one of the early Foundation stories (which ends by recasting this belief as a parable involving a horse agreeing to lend its speed to carry an armed human). It’s never been clear to me how much this was true vs certain people being willing to force control over other people; I’ve seen this dynamic on a small scale in local clubs and even at that level there are many threads going.

A possible example of overturning a debatable parliament for something better: S. F. Kuang’s Babel. A quote at the front from a history text suggests there will have been change, but the ending of the book makes this ambiguous — perhaps another doorstop or two will be needed to make things clear. Donald Wollheim took this to a conclusion in “Ishkabab”, in which a colonized people gradually take enough control of Britain (through energy, enterprise, and communal funding) that it releases the colony.

@22: Fanon prefers Moist von Lipwig or Samuel Vimes jr. (Young Sam) as the next Patrician.

@21 – we must remember that Vetinari strongly supported the idea of “one man, one vote”. After all, he was the one man and had the one vote.

The problem with labelling political systems is the same as labelling stories as a particular genre. Everyone can sort of agree on the definitions, but when you start using them to label stories, suddenly it’s an argument because it’s so subjective. People can’t agree where the demarcation between where one genre/sub-genre/political system ends and the other begins, because it’s kind of a spectrum and the border is fuzzy, woolly and kind of elastic. One sentient’s representative democracy is another sentient’s oligarchy. Everyone wants to claim a mandate to rule derived from the masses, so like to think of themselves as democracies, and label themselves as such. My old politics textbooks tried to deal with that by labelling “western-style” (their term) elected representative democracy as “liberal democracies”.

Here’s a few examples of what I mean about it being subjective. First, that old fall back: Star Wars. It’s got Mr Nicoll’s bête noire, royal titles. Yet on Naboo at least, the position of Queen is an elected position, and it seem like family members are given the corresponding royal-sounding titles to denote their relationship to the elected head of state, not their position in line of succession. That sounds like a representative democracy to me, despite the royal titles.

Then there’s RCN series by David Drake. On the surface, Cinnebar (the star nation the protagonists belong to) is a representative democracy. Closer examination shows that each election is won by the same group of people being drawn from the same families, or are only elected if they win patronage from one of those families. Social and military advancement is explicitly done through a patronage system, suggesting it’s an oligarchy. An even closer examination shows that the head of state, Speaker Leary, ever since he arranged the state-sanctioned murder of every one of his political opponents, (accusing them of treasonous conspiracy, with the suggestion that some might actually have been guilty), as well as their families, has been the undisputed ruler. The only thing limiting his authority seems to be himself. As such, Cinnebar seems to be an autocracy.

last example: the Star kingdom of Manticore in the Honorverse by David Weber. It’s a constitutional monarchy, so the head of state is selected gets to select their successor, usually one of their offspring. Their power is kept in check by the legislature, two Houses of Parliament, so despite having much broader powers than most constitutional monarchs, they aren’t autocrats. The senior House, and the one which the executive branch of government is recruited from, is an oligarchy. Like the monarch, members get to appoint their successors, usually one of their offspring. So it sounds like it’s an oligarch government. However, new members are appointed by the monarch with approval from the other House. The other, junior House is the House of Commons. There members are picked by a representative democratic system. They act as a check against the power of the monarch and the senior House, and a major plot point through several books in the series is the domestic opponents of the Monarch and her allies winning elections to take control of the House of Commons, and therefore the government. This suggests Manticore is ultimately a representative democracy.

However, the House of Commons (and the Executive formed from the mandate controlling it gave) were kept in check by the judiciary branch, membership of which was appointed by the monarch with approval from the Houses. Their power to veto policy and actions of the government could mean Manticore is ultimately an oligarchy.

So, yeah, it’s a pretty tricky task that Mr Nicoll set himself, and I’m not surprised at avoiding disclosing how he allocated specific instances. :)

As to why oligarchies are more common in fiction, I’d suggest that modern representative democracy is still to recent to have much of an impact on the stories that form us, so that impacts the stories that we tell. There’s also the way representative democracies are based around being both charismatic and popular across a diverse spectrum of demographics, and I’m guessing that there’s not a lot of crossover between being that (or the desire to be that) and the authors of sci-fi and fantasy stories. So instead they write about systems of government where other qualities equate to power.

@21 Suspect that Vetinari’s sneakily priming von Lipwig for the job.

In Charles Stross’s Merchant Princes series deals with a woman called Miriam from the 21st century US, finding that she is a member of a ruling family in a parallel world, who have used their ability to jump between the worlds to make money in our world (via drug smuggling mostly) and power in their medieval world (by importing and controlling access to things like antibiotics). Miriam being a modern woman doesn’t really fancy her chances in a hereditary aristocracy so starts trying to modernise it before the US Government finally works out how this particular criminal syndicate does so well, and how it’s members always seem to disappear when they’re caught…

Certainly an example of an oligarchy being reformed into a democracy (and also a democracy slipping into an oligarchy).

IIRC The Culture is technically an anarchy, because there’s no overall government, just ad-hoc committees. It’s still also a direct democracy, as well as fully-automated luxury space-communism. It all depends which part of the society you look at it, and how you define your terms. Pretty much everyone has their own idea of what ‘communism’ means, for example.

Anhk-Morpork on the Discworld is an interesting example of a society in transition. Over the course of the series, the political system doesn’t change, but it did seem like Pratchett was setting something up. Both Carrot’s family history and Night Watch shows the chaos that ensues from a regime change in an autocratic political system. Carrot also had a very vivid illustration in Feet of Clay of the expectations people would put on a new King, and his likely fate, for a man like him would try to embody those expectations with the result he’d either end up like the like the Golem King, or becoming like Vetinari, choosing practicality over morality. Feet of Clay also illustrated the vast inequalities present in Ankh-Morpork. Over the course of the series, we see the society under vast changes, managed by Vetinari, like the Industrial Revolution, moving from an agricultural economy to one focused on mass-production, from a mono-culture to a diverse multicultural and multi-species society, and from a metal-based monetary system to a paper-based one. There’s also subtle hints, with Vimes’ pain in the chest to Vetinari’s Stoker Harris persona (in the U.K., there’s a certain type of white-collar retiree that becomes steam train engine for fun, and I think that was Pratchett’s plan for Vetinari’s retirement, that he’d escape and disappear into Harris persona), that Carrot would soon have to step up.

What I find really interesting is the way Vetinari and Carrot’s relationship evolves. It starts with Vetinari recognising Carrot had a very real chance of successfully seizing control violently from Vetinari, but realising Carrot, even if he realised he could (and Carrot played the ignorant copper very well at times), Carrot had no interest in being in charge. It evolves to Vetinari recognising Carrot’s the most capable candidate to succeed him, and starts to coach him. Then note how in the last book, Carrot’s the one giving orders disguised as ‘suggestions’, and that Vetinari accepts all of them. Also note how the position of the new Watch Houses Carrot wants are good for maintaining civil order in the inevitable unrest that would follow the disappearance / apparent death of Vetinari.

I suspect Pratchett wouldn’t have wanted to kill off Vimes, so he’d probably have been carted off to retirement after having a heart attack manning the barricades, and that Carrot would have encouraged a (as someone else suggested) the Crackpot System (after a book to introduce it). So we’d have ended up with something like a Blue Bloods scenario: Carrot as the Police Commissioner/Watch Commander serving at the pleasure of the elected Mayor/Speaker/President, with Vimes being the grouchy former Commissioner/Commander dispensing advice. They’d be a new Mayor every few years, but none would dare sack him, so he’d offer stability while the idea of democracy sunk in, but crucially for Carrot, he’d not be in charge. So technically it would be a representative democracy, rather than an autocracy.

Vetinari, like Bujold’s Aral and Gregor, is an actual enlightened despot. He presumably knows that he’s unusual as a Patrician, given that his younger self was ready to murder an earlier one on general principle. There is exactly zero democratization in Discworld, which makes you wonder, but Vetinari does spend the latter part of the series building up _civil society_. Watch, newspaper, post office, banking, precedent that he himself can be arrested for ‘crimes’.

Granted, the rebuilt Watch and maybe the newspaper are initiated without him, but he seems to run with it afterward.

So it’s possible he was building up a less autocratic system (though on the face of it that just favors the Guilds and nobles, oligarchy) and the pre-conditions for more popular say.

Elected monarchy is a common thing in history, though typically from a limited candidate pool (e.g. one extended royal family). I like to say that the minimum level of democracy is being able to peacefully _un_elect your leader. Picking new leaders at random but making it easy to bounce them would be more democratic (and certainly has more ongoing feedback) than electing a new leader for life.

Thinking about it, you can say the same thing about representative democracy. By definition it has multiple, competing parties (and factions within them), and as a practical matter there are usually relatively few (between three and seven is globally typical). The characteristic events – elections, votes of confidence, coalition formation or collapse – are reliably drama-generating.

Speaking as a research-trained social scientist, I agree your avoidance of “king” and “queen” and the like has probably markedly distorted your results. I would suggest adding a distinction between SF and Fantasy, as in the past, at least, a disproportionate amount of fantasy has been in some version of European medieval feudalism (though the trend towards more diversity should be undoing that, thank God). I suspect the distribution would be different between the two.

I also think that, as always, SF is often really talking about today, and there is no doubt that there are strongly visible oligarchies throughout the world today now, which would influence what people are choosing to write about, since many SF novels in particular look for solutions to (or at least rebellion against) perceived current problems. If you did the same cut on stories from, say, the 1940s-1950s, you would probably see a lot more authoritarian states as the bad guys, given the focus on anti-fascism and anti-Communism in many of those novels.

And there’s no doubt that oligarchies provide great fodder for conflict if you want to do a politically-minded story rather than a straightforward “kill the king, conquer the empire” kind of story. It has been my observation that SF has been getting considerably more sophisticated on this front in the past few decades, which is another reason your current count is probably different from the 1940s-1950s, where with few exceptions, no one seems to really understand what a leader does with their day. (I assess and develop executives, so this is a constant irritation to me!)

One in five of my reviews are of books I read as a teenager in the 1970s, so there may be more old time SF novels in there than you expect.

Now do Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota <evil cackle>.

I love the article and the comments show it really interests a lot of people. It is, as described, small and limited, but a survey like this can reveal a lot!

My two takeaways were:

Fantasy and SF =/= Autocracy. I did not expect it would be so far down the list. And even if we could dispute which governments are depicted in a given book, it seems like a good rough cut. After all, it can be tricky just to say whether a book is SF or Fantasy.

It’s weird that I thought autocracy would be higher on the list when it is so far down, and clearly I wasn’t the only one. I wonder why that was my preconception? My guess is that classics and TV adaptations in the genre get discussed a lot and come easily to mind, like LOTR or ASOIAF, and less so for Memoirs Found in a Bathtub by Stanisław Lem or Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson.

Eric Frank Russell wrote several anarchist stories for Astounding in the ’40s. AFAIK he popularized the acronym MYOB. His anarchists were mostly pacifists who believed in small political units governed by consensus. Violence was a last resort. Hilarity ensues when they come in contact with ships from the Empire.

@43: Russell may have popularized MYOB within the SF community, but its usage in American slang dates back to at least 1846. Often a nosey-parker would be invited to “join the M.Y.O.B. society.” (Ref: etymonline.com/word/myob)

Very late to the game here, but I’m wondering if beyond selection bias there’s also a category problem? Where would you put Joan D. Vinge’s Outcasts of the Heaven Belt, which features two (three) competing cultures with very different systems of government?

@46 Or, for that matter, Delany’s Triton. On the titular moon, they hold elections regularly, and each individual is governed by the laws of the party they vote for. (There is also a “U-L,” an Unlicensed Zone, where no laws exist at all.) A “Heterotopia” indeed!