Relativity! Extremely well supported by the evidence, and extremely inconvenient for SF authors who want jaunts to the galactic core to be as easy as popping down the road. Given a universe so large that light takes as long as anatomically modern humans have existed to meander across a single galaxy, combined with a very strict speed limit of C, and you face a cosmic reality that makes many stories authors might want to write quite simply physically impossible. So… what are hardworking science fiction authors to do?

Disregard the Issue

By far, the most popular option is to ignore the issue or actively deny that it is an issue. Maybe Einstein divided when he should have multiplied (he didn’t). Perhaps light speed can be surpassed given sufficient will (it can’t). What if some miracle material for which absolutely no evidence exists could facilitate superluminal travel? (More likely, such materials are simply non-existent.)

One might excuse an early example, such as Doc Smith’s The Skylark of Space, on the grounds that the novel was written early enough that relativity had not yet earned by weight of evidence the overwhelming consensus it now enjoys. I don’t know if a physicist of that day would have agreed, but they might have admitted that Smith’s handwaving facilitated a thrilling tale of galactic-scale interstellar travel uninhibited by physics or indeed, basic literary values.

More than a century of research suggesting that Einstein was right hasn’t stopped authors from imagining faster-than-light drives. Julia E. Czerneda’s 2001 In the Company of Others features convenient and affordable faster-than-light travel, not to mention an abundance of easily-terraformed planets suitable for human exploitation. The cost: if it’s easy to explore the Milky Way, it’s possible to encounter a lifeform one would have been better off never contacting. In this case, that would be the Quill, a seemingly harmless lifeform that by the novel’s beginning has wiped out human life on all colony worlds.

Accept the Universe the Way It Is

Yes, that means giving up dreams of galactic communities where a gentle being can send a message to Sirius before breakfast and get a reply by lunch. But… embracing the universal speed limit and scale only rules out most interstellar adventures. Fun in our Solar System is still possible! Well, to backtrack a bit, relativity does not rule out interstellar adventures, just as long as one accepts that such endeavors will be inherently difficult and time consuming…

Arthur C. Clarke’s 1975 Imperial Earth, set during the American quincentennial, dispatches Duncan Makenzie from his native Titan to Earth. The ostensible reason for the trip is diplomatic outreach between the US and resource-focused Titan. Side projects include saving Titan’s economy from being destroyed by an impending drop in demand for their primary export and dealing with Duncan’s excessively fraught romantic life.

Ari North’s 2020 webtoon/graphic novel Always Human is likewise set in the not-too-distant future, one in which most but not all people have access to life-enhancing body modifications. Austen is one of the unlucky few; she has an autoimmune disorder that precludes using mods. Sunati, smitten with the imaginary Austen she has invented based on a few brief public transit encounters, successfully woos Austen. Will the relationship prevail or is it doomed by inherent communication issues and career choices?

Yes, there’s travel within the Solar System in this webtoon/novel.

Move the Stars

Adherence to scientific plausibility would seem to rule out interstellar travel, at least of the convenient variety. There is a loophole. Use settings in which one or more stars are closer to us than they are at present1, which is entirely possible because STARS MOVE.

In John Brunner’s 1982 Catch a Falling Star, astronomer Creohan observes a star making a beeline for the Solar System. The consequences of a close encounter could be catastrophic. Inconveniently for Creohan, his Earth is a decadent one—even had it the means to deal with the crisis, it does not appear to have the will.

More recently (and yet somehow still decades ago) Donald Moffitt’s Orientalist 1989 space opera series Mechanical Sky showcased an ambitious sultan whose solution to interstellar distance was to exploit Moffitt’s comprehensive misapprehension of basic physics certain curious aspects of near-light travel to move the stars themselves. Even a single cubic light year is a very large volume of space, more than enough to house a vast number of systems.2

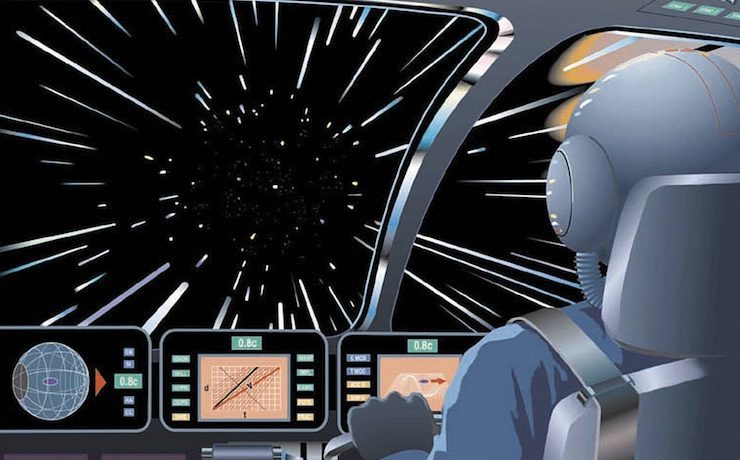

Time Dilation

Relativity itself offers a useful coping mechanism in the form of time dilation. The duration of a trip varies according to the observer. When relative speeds are low, clocks will agree. A traveler who travels close to the speed of light or at the speed of light will experience less time than that measured on Earth. The catch is that travelers who return home will find worlds transformed by time.

The golden age of Bussard ramjets was filled with such stories. In Larry Niven’s 1976 A World Out of Time, Jerome Branch Corbell, a reincarnated3 20th century man, hijacks the Bussard ramjet with which he has been entrusted and takes a jaunt to the core of the Milky Way and back. An encounter with the black hole at the core of the galaxy sees Corbell return to the Solar System millions of years later, time its inhabitants have used to dramatically alter our home system.

Increase Lifespan

Finally, perhaps the issue isn’t that star travel is inherently time-consuming. Maybe the real problem is that humans are fragile mayflies. Increase lifespan significantly and voyages once far longer than any reasonable lifespan become, if not practical, then at least achievable.

Consider Linda Nagata’s 1998 Vast. Not only do its characters inhabit a sub-light starship far superior to any we might now build, but they have access to life-extending technology that can, under the right circumstances, make death itself a temporary inconvenience. Given the hostility of the galaxy they are exploring, such life-extension technology is invaluable.4

***

These are just a few of the options available to authors who want to acknowledge the light-speed limit while still crafting thrilling space adventures.5 No doubt I overlooked or didn’t have space for some ingenious alternatives. Feel free to mention them in comments below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]Using wormholes might be considered a subset of changing the distance between the stars. A photon traveling down the same traversable wormhole as a spaceship would beat the spaceship to the end. The spacecraft is in no sense going FTL. It is just that some paths though spacetime are shorter than others. However, there doesn’t seem to be much real evidence for traversable wormholes.

[2]There might be a large number of systems for a time (long in human terms, short from an astronomical viewpoint). I would guess that artificial clusters are subject to the same processes that scatter natural clusters.

[3]It was an utterly mundane reincarnation: the dead man’s memories were installed in the body of a mind-wiped felon.

[4]This reminds me of David J. Lake’s Breakout novels. Almost every starfaring species in that setting are functionally immortal gods whom sensible people avoid. Humans are the exception, relying on hibernation and applied hubris rather than extended lifespan.

[5]I wonder how many comments it will take before the conversation turns into one about surpassing the speed of light? Will this be a variation of Nicoll’s Law? Nicoll's Law: It is a truth universally acknowledged that any (online forum) thread that begins by pointing out why stealth in space is impossible will rapidly turn into a thread focusing on schemes whereby stealth in space might be achieved. (You can find this at http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/glossary.php, but it’s way way down the page.)

Le Guin: ships are barely slower than light. People travel to distant stars in a short amount of subjective time, and just accept that they will never return to the home they left, only to a many years later descendant of that home. Also, someone figured out how to send messages instantaneously across light years.

Cherryh and many others: ships are faster than light because of hyperspace/jump points/wormholes/some other handwave reason. However, communications are light speed limited. News from distant stars has to be carried by a ship that makes the journey.

Feh on stupid typos in the name field, that was me.

@1 and 2: Thanks for that. I was tempted to post merely to ask the significance of the misspelling!

Ansibles break relativity just as effectively as FTL drives.

There was also at least one Hainish story about testing an FTL drive.

A second FTL drive: Rocannon had FTL missiles. It was just living beings who were limited to NAFAL. The second FTL drive seemed to have unfortunate effects on reality.

As I recall, at one point it occurred to Johnny Chase, Secret Agent of Space! to wonder how if lightspeed is a limit, his ship was able to get from A to B faster than a photon would take. The answer from his ship was wilfully obfuscatory but it may have involved NAFAL travel + time travel.

Karl Schroeder had a very different solution in “Lockstep” & other stories set in the same universe: the people on the worlds hibernation 99% of the time to match the time dilation of interstellar travelers.

8: It occurs to me Lockstep could be seen as a metaphor for how we arrange cities around the convenience of cars, rather than the people who live there. My favourite example used to be a local pedestrian crossing where the pedestrian crosswalk light only turned green if a button was pushed, said button being on a post on a traffic island one busy lane from the curb.

@6 I thought the implication was not so much that churten is inherently damaging to reality as that you have to be *really, really, REALLY* careful who does it.

There’s a fascinating sub-genre of SF fandom discussion that focuses on being sniffy about authors violating the light speed limit. It doesn’t seem to happen for other highly implausible future technologies — cryogenics, people living forever, etc — but world build with FTL and the head shaking starts.

@10: I’ll see that and raise you thermodynamics.

Animals hibernate so suspended animation doesn’t seem impossible. Living forever appears to be ruled out by cosmology, but living longer doesn’t seem impossible. However, FTL appears to be definitively ruled out by all the evidence we have, a very different case from the other two.

That said, lots of nonsense is accepted in SF without blinking an eye. Psionics, for example. Human societies that survive unchanged for thousands of years. Alpha Centauri being the nearest star a billion years from now.

@11 Good point!

@12 We could argue about specific examples but I think my point stands.

(I’m resisting the impulse to point out that every generation is absolutely utterly sure about some scientific conclusion which then turns out to be utterly wrong)

“Implausible” is not the same as “breaks the concept of cause and effect”.

Faster than light travel is equivalent to a time machine. http://www.physicsmatt.com/blog/2016/8/25/why-ftl-implies-time-travel is just the first hit; I haven’t time to get a better one. My understanding is that, if a ship can get from point A to point B faster than light, no matter by how little, then (with sufficiently powerful rockets) there exists a trip from B back to A that arrives before the ship took off.

James Nicoll @12 — The problem with “hibernation” comes when it involves complete shutdown of metabolic processes (e.g. the body is frozen solid) but not of nuclear ones (e.g. in time-stop fields) for time periods on the order of thousands of years. The decay of natural carbon-14 causes genetic damage, which normally either is repaired by cellular mechanisms or results in the death-and-replacement of the cells in question. Wait long enough with enough damage accumulating but no repair happening, and you’ll have a very sick organism.

@15: Ook. Background radiation would be a concern, as well.

15: Real hibernation would differ from SF hibernation in much the same way real CPR differs from movie CPR.

(Sure, I’ll try giving someone CPR under the appropriate circumstances. It’s not like they can get more dead)

In Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker, there’s a point where civilizations have settled into planetary hiveminds with radically inhuman conceptions of time, so they can interact with one another like separate individuals. I’ve always liked this model, though I find it difficult to imagine what post-singularitarian hiveminds would talk about.

(Unfortunately Stapledon also uses relativity-breaking telepathy in the same book).

There’s Robert Reed’s Greatship series. A crew of nigh immortal humans run a STL vessel the size of Jupiter’s core around the galaxy, charging fees for one of the safest ways to travel – between the hyperfiber armor, immense lasers and the solidity of the ‘ship.’

I see someone beat me to Lockstep, but there’s also the Virga series, a setting designed to allow all the tropes of space opera without the inconvenient relativity, etc.

And Charles Stross’ Neptune’s Brood is an explicitly interstellar civilization (with economy!).

Then there’s James Cambias’ Billion Worlds series. It’s “just” the Solar System, 8000 years in the future with settlement out to the Kuiper belt. But it doesn’t lose track of how big it is. It also has AI, genetic engineering, uplift. Very much a “yes and….” setting.

I must point out that warp drive and wormholes do not ignore or violate relativity; rather, they use the equations of General Relativity to circumvent the lightspeed limit established by Special Relativity. People tend to overlook that the Special Theory was for a specific set of conditions to make the math easier, while the General Theory, well, generalized it and established that the Special Theory only applies on a local scale. For example, there’s no reason why two different parts of the expanding universe couldn’t move faster than light relative to each other, and that’s what must have happened during the inflationary epoch. Relativity, taken in its entirety, does not prohibit relative movement faster than light, as long as it’s a function of changes in spacetime topology; it merely prohibits accelerating to or beyond the speed of light, because it would take infinite energy to reach it. You already mentioned one example, wormholes, in your footnotes.

What FTL violates is not relativity, but causality, since it potentially creates paradoxes of people being aware of events before they happen. But I don’t see that as a problem, since time is probably immutable. There are some theories, like John Cramer’s transactional quantum mechanics, which posit that it’s normal for information to propagate back through time on advanced waves and influence past events, such as causing a photon in a slit experiment to “know” in advance which slit(s) it will pass through. In which case, information from the future doesn’t create a paradox, because it was always part of the way events happened and doesn’t change anything.

You might ask what it says about free will if people can learn the future but be unable to change it. But free will is always limited by context. On an open plain, you have the freedom to move in any horizontal direction, but not vertically. Fall off a cliff, though, and your freedom to choose your direction of motion becomes far more constrained. Time travel or warp travel (same thing, effectively) might be the same thing, a special physical circumstance creating constraints on personal choice that don’t exist in non-time travel situations. (I address this in a couple of stories on my Patreon’s fiction tier, namely “The Moving Finger Writes” and “You Have Arrived at Your Predestination.”)

In Vernor Vinge’s “Zones of Thought” books, the rules of the galaxy change depending on how far you are from the galactic center, going from the “Unthinking Depths” (where intelligence itself is impossible) to the “Slow Zone” (where FTL is impossible) to the “Beyond” (where FTL is possible and gets better the further out you go) to the “Transcend” (where super-intelligences are possible)

20: This sounds like the difference between the expanding universe as a whole, and the observable universe. Yes, the observable universe has a radius of about 45 billion light-years, although the universe is less than 15 billion years old.

That doesn’t mean you can get here from here (even if “you” are a particle moving at the speed of light).

An approach I like (and which I take in my own comics) is to embrace the storytelling that’s enabled by being subject to relativity and finite travel speed. Colonization is a slow, deliberate process where the inhabitants of the generation ships come to see the ships themselves as their native habitat and forget what planets even are. Any colonization that occurs is because of a mandate of self-preservation and not because of any attempt at establishing galactic-scale commerce and communication. It’s all about preventing decay and staving off entropy as long as possible, and everything dies, eventually.

Speaking of Smith: I can’t speak to Skylark, which largely avoided the whole topic. BUT in the Lensman series (First Lensman I believe) our stalwart heroes have built their spaceship and are talking about how because of relativity they won’t be able to go too far. Press the button, check the star-fields and they are 20 light-years away. One of them turns to the other and says:

“Well, I guess Einstein’s theory was only a theory.”

22/Vicki – Except it’s the Einstein field equations governing both, so it’s not clear why one would be permissible but the other not. Granted, the only warp drive concept we have requires regions of negative energy to work, but it’s at least a mathematical possibility.

@19/Pilgrim: “Then there’s James Cambias’ Billion Worlds series. It’s “just” the Solar System, 8000 years in the future with settlement out to the Kuiper belt. But it doesn’t lose track of how big it is. It also has AI, genetic engineering, uplift. Very much a “yes and….” setting.”

I’ve often thought it would be cool to work in a setting like that. It could be a fun way to do a modernized take on old universes like Buck Rogers or Rocky Jones, Space Ranger, where there are “alien” humanoid civilizations on Mars, Venus, and other planets in the Solar System.

@22/Vicki: The point is that the principle behind warp drive and wormholes is the same as the principle behind cosmic inflation: that there is no speed limit on how fast spacetime itself can distort, only on how far you can accelerate in normal spacetime. Using spacetime distortions like wormholes, warp bubbles, or spatial folds to achieve effective superluminal travel is not violating relativity, it’s using General Relativity to transcend the limits of Special Relativity, which is just a limited case of the General Theory.

@24/Dr. Thanatos: “One of them turns to the other and says:

“Well, I guess Einstein’s theory was only a theory.””

Ouch — I hate it when people misuse “theory” that way, as if it were less than a fact. A theory is more than a fact. A fact is a single observed data point. A theory is a model that explains the causative mechanism behind a whole set of observed facts and makes predictions that can be verified or refuted with further observations. A theory is a theory whether it’s proven or not.

I can’t think of the titles right now, but I know that at least once or twice I’ve seen setups where a large amount of matter consisting of atoms quantum entangled with atoms left behind, is sent STL to another solar system, and then the information transfer inherent in spooky action at a distance is used to communicate or even recreate people.

Charles Stross’s Saturn has the solar system populated by immortal robots*- who turn off their consciousness for long STL spaceflights.

*I forget if we pesky humans die off naturally or succumbed in the robot uprising.

@26 Christopher,

I do not disagree. I love, however, the attitude it projects. “Oh well, we just proved relativity wrong. Now let’s kick some Eddorian butt…”

Well… there’s always Heart of Gold in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Infinite Improbability Drive — let’s break reality and cruise through every point in space at once! It surely is somebody else’s problem.

28: Humans declined to have enough babies to compensate for the death rate and went extinct.

@Dr. Thanatos: You are confusing your series. The exchange about Einstein was in The Skylark of Space. It was the Lensman series that neutralized inertia and then ignored relativity.

FTL doesn’t necessarily break causality if the universe has a preferred reference frame, but a preferred reference frame breaks relativity.

I have a feeling Babylon 5 jumpgates were supposed to work like that, but it might have just been a fan theory. Once you open one jumpgate, it restricts what other jumpgates can be created, so that a time-like loop was impossible or destroyed the instant it was created. That conflicts with relativity, but not with observations that don’t include hyperspace jump points.

Babylon 5 did also have causality breaking time travel, but the characters seemed sure that was different from FTL travel.

Cherryh’s Alliance/Union stories combine a form of FTL with a variation of move-the-stars-closer; she observed that even this far out from the core, our sun is unusually far from any other stars, and proposed that Earth would become a backwater once there was a human presence around a star with closer neighbors.

It has been a long time since I read any Chandler, but I recall his Mannschenn Drive involving movement in both space and time; was it an AAFAL relativistic drive that used time travel to let ships be at their destinations in a reasonable time and at the appropriate age, or did he never get that specific about why time shuffling was a part of it?

@27: an example: Stross’s Singularity Sky and Iron Sunrise. ISTR he intended more stories but got tripped up by new research results, although I may be confusing that with another of his very short series.

@32 Allan

I admit my error. I should be subjected to the collected recorded speeches of the Fenachrone.

Futurama – the spaceship is stationary and the engine moves the universe around it

Bob Shaw’s Orbitsville and sequels tried to explain FTL by saying that the limit didn’t exist once you got out far enough into interstellar space – he didn’t really explain why we don’t notice this by most of astronomy making very little sense, unfortunately. I seem to have lost my copy somewhere so I can’t quote the precise explanation.

17: (Sure, I’ll try giving someone CPR under the appropriate circumstances. It’s not like they can get more dead)

It’s my understanding that you are basically giving the person a much better chance for when the ambulance actually arrives, so it’s almost always a good thing to do if they aren’t breathing.

The Return Problem is really even a bigger issue for SF adventure authors than just FTL. Not only do our heroes get someplace faster than the speed of light would allow for the distance of their destination, but they get to go back and virtually no time has passed since they left! All the same people are still alive and plans hatched prior to the voyage can still be followed through after it’s done. All of those tricks like wormholes or “hyperspace” that let one cross vast distance via some alleged topological shortcut are designed to allow the voyagers to get back to the Empire in time for tea (or their wedding). Apologies to the author if I’m mistaken, but I believe in Sisters of the Vast Black the sisters leave one star system for another, then get a distress call from the planet they left that lets them pop back and save the life of a former acquaintance there. Even traveling between distant planets within one solar system that would not work out so easily. But there are plenty of other examples like that.

The interstellar empires that are imagined all seem to have far-flung worlds operating within the same timeframe as if they were outposts of the Roman Empire, and battles in space take place in the same timeframes as Hastings, Trafalgar or Midway. Not plausible with relativistic one-way FTL.

I actually wrote a comic with an immortal character who deals with complications due to this. He travels in a ship that can achieve something very close to light speed, but the distances he travels would still be impossible to traverse in a normal human lifetime, even from the point of view of the person traveling (I even made a spreadsheet about it XD). I also illustrate that communication is bound by the speed of light – every time he gets a homing signal from a civilization, by the time he reaches the location, entire civilizations are gone because it takes the signal time to get there, then it takes him time to travel. I mean there are a lot of spots where I was like “not dealing with that” and handwave stuff or pretend it magically works (like artificial gravity on the ship so i could achieve the aesthetic i was going for lol) but when it comes to intersteller travel, i did pay some attention to science. Is anyone interested in reading? Would it be ok to share my site here?

@35

Mamma, don’t take my Fenachrone away…

(No doubt some filker has already done that.)

In the Chronicles of Solace trilogy by Roger MacBride Allen, there are wormholes, but they are strictly time-travel mechanisms. So you do FTL travel by a combination of STL travel in sleep/stasis and wormhole travel to go back in time. The Wormhole Patrol or whatever makes sure ships use them properly, like no going forward in time (for regular folk). I’m not sure that scheme helps anything, but it’s an interesting twist.

Time dilation was also used in the original novel by Pierrce Boulle and movie Planet of the Apes as well.

I’m still rather proud of the concept behind my comedy series “The Hub” from Analog. The Hub is a warp at the galaxy’s center of mass (offset from the galactic core because of the distribution of the satellite galaxies, and thus accessible) that allows instantaneous travel to and from any point within the galaxy’s dark-matter halo — but it’s the only means of FTL that exists, so all interstellar travel has to pass through the Hub. Also, it’s impossible to predict where a new dive vector into the Hub will come out, so they have to be tested through trial and error. And the impact of that on galactic society, politics, commerce, and the main characters’ lives has driven six novelettes so far, and hopefully more to come. It’s just one concept, but it generates so many angles worth exploring.

@38/James Williams: “It’s my understanding that you are basically giving the person a much better chance for when the ambulance actually arrives, so it’s almost always a good thing to do if they aren’t breathing.”

Yes, exactly. The point of CPR is to keep the brain oxygenated by keeping the blood flowing.

I did not read all the comments so that this method could have been mentione above. The way to get out of the “faster than light speed problem” has been explained in many Sci Fi stories, I am just repeating what has already been said. That is the method of “folding space.” You can actually simulate this process on earth!!! What you do is take a piece of paper and put two dots on said paper. Then you “fold” the pape so the dots touch each other. Than you put a string through the dots. Viola you have solved the “light speed” problem becuase you are not actually moving. There is no speed limit to have to over come!!

Of course, GR is a geometric theory but one of intrinsic geometry. There’s no reason to think spacetime has an extrinsic geometry.

Of course, while GR (and quantum mechanics) are both incredibly well-tested, they both have one issue: they’re can’t be reconciled with each other.

@14: If there is ever an FTL drive developed, the concept of causality would be need to be revised. Of course, travel through wormholes isn’t faster-than-light, so there wouldn’t be any causality violation from that. Of course, neither wormholes nor Alcubierre drives are likely to be physically realizable, what with that need for likely non-existent exotic matter.

Something like LeGuin’s NAFAL or most of the other relativistic drives are likely impossible due to the energy required to accelerate a significant mass to relativistic velocities. The kinetic energy of a 1 kg object traveling at 99.5% of the speed of light is something like 9×10^17 J. Of course, the US annual use is about 1e20 J, so it’s only 1% of that. And let’s not forget the relativistic rocket equation.

CPR success rates outside a hospital are pretty low, I think about one in seven (plus good odds of injuring the patient). However, the success rate of doing nothing at all is much lower than that. CPR can greatly improve survival rates but those rates still aren’t great. So do CPR but be prepared to have the patient die anyway.

@48/James: Yeah… I’m tired of the way fiction portrays CPR as this dramatic way to bring people back to life — or as something you give up on after a few minutes if it doesn’t “work,” when the whole point of it is to maintain circulation as long as necessary until other methods can be brought to bear. I’m almost as sick of it as I am of the depiction of defibrillators as the equivalent of jump-starting a dead battery.

As for hibernation, I gather there’s very promising ongoing research into putting humans into long-term torpor similar to animal hibernation, and that it slows deterioration in ways that could have valuable medical benefits as well as space travel benefits: https://www.space.com/astronaut-hibernation-trials-possible-in-decade

Here’s another article that talks about hibernation research for spaceflight:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2020/08/25/aspects-of-interstellar-transhumanism/

According to it, the most you could slow life processes is by a factor of 10-12, so that you’d age roughly a month for every year in hibernation. Which means it might be viable for journeys of decades, but it’s be pushing it to try to freeze someone for a century or more.

It is very useful to have more than one person trained in and able to perform CPR, so people can swap out when they get tired off CPRing to the beat of “Staying Alive.”

@48: plus good odds of injuring the patient

The phrasing I’ve seen is that if you’re not breaking ribs, you’re doing it wrong.

It seems that wormholes are all the rage for FTL travel. Just don’t ask about the details.

Wormholes. Just wormholes. Everyone’s favorite Dues Ex Machina.

Tau Zero by Pulse Anderson is about a ship whose drive malfunctions and which continues accelerating through space, and how the passengers are affected as the ship continues to move through dilated space. The physics is thorough and eloquently described and it’s a great book overall. Anderson and Niven are two of.my favorite authors.

Michael Bishop (I think) had a novel where every trip translated into creation (move between) parallel universes. It was nto exactly a relativity speed travel, but allowed for fast “travel” between stars.

55: also John Scalzi, Old Man’s War.

@10: There’s a fascinating sub-genre of SF fandom discussion that focuses on being sniffy about authors violating the light speed limit. It doesn’t seem to happen for other highly implausible future technologies — cryogenics, people living forever, etc — but world build with FTL and the head shaking starts.

The example of this that always comes to my mind is the Orion’s Arm shared online SF universe. The creators of the site made a point of saying that they considered their setting to be hard science fiction and scientifically plausible – specifically, that there was no FTL travel (in the sense of ships with warp drive, etc.). At the same time, the setting includes godlike AIs, as well as genetic engineering and nanotechnology with virtually unlimited capabilities, which to me seemed to stretch the boundaries of plausibility essentially as much as FTL travel would have done.

(Orion’s Arm does have FTL travel in the form of traversable wormholes, with the caveat that such wormholes require an immense amount of infrastructure at both ends; thus, establishing a wormhole to a new location requires transporting the infrastructure there at slower-than-light speeds, setting it up, and opening the wormhole back to the origin point. In addition, while communication still travels at the speed of light, communication signals can be sent through a wormhole to effectively enable FTL communication. I do think that there were discussions of the issues of the time differences created by the combination of STL travel and wormholes.)

@54: “The physics is thorough and eloquently described and it’s a great book overall.“

Right up to the last few pages. Then it’s as if he realized he had no ending, and just handwaved total insanity.

@41 that’s pretty good.

Back in the day (1970’s) we would do “celebrity D&D” and one time it was Dirty Harry and Valerie Bertinelli captured by a troop of Fenachrone…

@53: And if they’re not called wormholes they are called “gates” (“jump gates”, etc.) and were supposedly constructed by some lost and far technologically superior civilization. Anything to allow the plot to proceed along familiar colonial British Empire travel and communications timeframes. At least in The Freeze-Frame Revolution (Peter Watts) the consequences of relativistic timeframes play out for the human crew of the starship building the gates, so they have no idea if the rest of the human race still exists as they continue onward building gates for other people’s use.

@27 “I can’t think of the titles right now, but I know that at least once or twice I’ve seen setups where a large amount of matter consisting of atoms quantum entangled with atoms left behind, is sent STL to another solar system…”

Orson Scott Card’s 1985 “Ender’s Game”, comes to mind, with its entangled particle, instant, infinite range “ansible” communication technology.

Even Card acknowledged that this was just a plot device, and that entanglement can’t be used send signals faster than light. In short, this is because while entanglement means that when you measure some complementary property of one particle you know instantly what the state of its distant, entangled partner, it’s impossible to force the measurement to have a predetermined value, so no way to send any sort of information-carrying signal.

I’ve long judged SF space travel stories by how they address the issue of the causality violation inherent in FTL communication or travel, using a 4-point scale:

-1-FTLC/T impossible, explained (eg: “Mindbridge”, 1976 by Joe Haldeman);

0-FTLC/T impossible, assumed (most hard SF);

1-FTLC/T possible, causality violation addressed (eg: “Timescape” 1980 by Gregory Benford, “Exulatant” 2004 by Steven Baxter);

2- FTLC/T possible, CV not addressed. (practically all space opera)

Some series/authors start at a hard 0, then “jump the FTL shark”, as I put it, to a 2, eg: the wildly popular “Expanse” series, 2011-2021 by James S A Corey

Digressing from the subject of the problem of relativity in SF: many stories that keep their 0 rating by sticking to slower than light travel, like the Expanse series until it doesn’t, play fast and lose with energy.

Corey (Abraham and Franck) explained in one of their afterwards that they had to exaggerate, by IIRC about a factor of 10, the energy of the series’ fusion-powered, water-reaction mass rockets to allow, via the “Epstein drive”, ships to sustain 10 m/s/s accelerations throughout interplanetary flights.

If Fusion doesn’t give the needed energy density for something like the Expanses’ spaceflight, the next and last better technology is antimatter. In his non-fiction/illustrating fiction book “Indistinguishable from Magic” (1995), Robert Forward gave a pretty convincing account for how ships like the Expanses’ could work if powered by antihydrogen, while describing the Kardashev scale jump in engineering needed to get the needed quantities of it, which he imagined would require dedicated solar powered particle accelerators based factories in close orbits around the sun.

This comes around to a perennial problem in trying to make hard SF plausible, space opera-compatible spaceships: giving them the energy density they need to fly around in an entertainingly satisfying way requires they have stuff – antimatter – that can be used in such devastating weapons that there’s little entertainment or purpose in flying around entertainingly. Damn the cold equations of hard SF!

@60/Paul Connelly: “And if they’re not called wormholes they are called “gates””

It bugs me that the Internet Speculative Fiction Database insists on labeling my Hub series as “Hub Gates.” There aren’t any “gates” in it; there is one Hub, singular. That’s the whole point of the premise.

62: Also, super duper 1 gee forever rockets imply nuclear-power-station level output from something the mass of a Volvo, which under most circumstances the civilian economy would have access to. If it makes economic sense to accelerate cargo to .01 C or more and down again, it’s probably makes as much sense to use the same energy per kg in other ways and the author needs to consider that.

I think Ben Bova had “super fusion rockets” + “global energy crisis” in the Grand Tour books.

Charles Sheffield has a good reason not to use his rocket power source on Earth: the rockets used very small black holes and the worst case scenario of a mishap ruled out Terrestrial use.

James@64, this also applies in spades to wormholes if they’re explicitly built via exotic matter. Exotic matter violates the weak energy condition (banning it is basically what the weak energy condition is for). That’s not a minor thing: obviously you get repulsive gravity, which means you get perpetual motion machines, objects repelling other objects that are attracted to them in turn, objects accelerating without bound with zero energy input, oh and the immediate destruction of the vacuum and the end of space-time because all this applies just as much to spontaneously created particle/antiparticle pairs.

The first lot has been used in some SF (I believe Weber uses something similar in _Path of the Fury_, which is a good book to read when covidated), but it’s hard to see how anyone other than perhaps Greg Egan could use the immediate destruction of the vacuum in a story. It’s a bit… final. (Also, he’s done it, in _Schild’s Ladder_, with the important point being that the destruction proceeds at only half c and is not caused by the weak energy condition being violated so there is some hope and room for a plot. Older Baxter has done it too, but of course older Baxter is all about finding ways to destroy the world/galaxy/universe so he got a big boom at the end of the book and could sweep all the consequences of the plot under the rug.)

@65/Nick Alcock: I think there are some wormhole theories that get around the exotic-matter thing by relying on locally negative energy, still positive in the absolute but negative relative to the surrounding spacetime, like the Casimir effect.

It’s not flattering to us but—suppose we can’t find a way to travel faster than light because homo sapiens is too stupid? We may be incapable of breaking the C barrier because we lack the brain power.

That does not mean there are not creatures out there who are two or three times smarter than we are. What would their scientific revolution look like? Traveling from one star to another might be as challenging to them as riding a city bus is for us.

67: Given that my day began with bus doors refusing to let people disembark and ended with two different buses mysteriously vanishing from their routes…

@67/Fernhunter: Actually we already have a pretty good idea of what it would take to get around the lightspeed limit — see what I said before about General Relativity vs. Special. We also know the immense practical difficulties in making happen, but there have been some impressive theoretical strides toward making it potentially somewhat less prohibitively impractical. So I’d say if it’s doable at all, we’re already on the right track to figuring it out, and just need more time — say, maybe a few thousand years.

The thing about science is that you can find things out by looking at the universe and letting it tell you how it works. It’s not dependent on how smart you are, as long as you’re smart enough to be willing to learn. After all, no matter how smart you are, you’re still living in the same universe, so it’s still gonna work the exact same way. As long as you keep learning about the universe, you’ll eventually arrive at the right answers. It doesn’t matter how smart you were to start with; you get smarter by learning.

@67: That’s the punch line of Harry Turtledove’s “The Road Not Taken”. Not only is it set in a universe where FTL is possible (unlike ours), it is so incredibly easy most civilizations accidentally hit on it right around the time they’re figuring out steel and black powder – and it comes with a free side of antigravity. For some reason humans never caught on, which leads to some nasty surprises.

(The make-the-text-white trick does not work on iPads. Enjoy your spoilers.)

I don’t know how much individual intelligence would affect the progress of science; I think that it’s fundamentally a collective endeavour. I suppose that there may be some insights that could only come from the mind of such and such a genius,

@@@@@ 70. Patrick Morris Miller

@@@@@67: That’s the punch line of Harry Turtledove’s “The Road Not Taken”. Not only is it set in a universe where FTL is possible (unlike ours), it is so incredibly easy most civilizations accidentally hit on it right around the time they’re figuring out steel and black powder – and it comes with a free side of antigravity. For some reason humans never caught on, which leads to some nasty surprises.

Poul Anderson came at it from the other direction in Brain Wave. Humans and most other species evolved within a galactic field that slowed down neurological processes. When our solar system followed our galactic arm out of the field, everything on Earth got a lot smarter. Humans figured out how to travel faster than light. But when one FTL ship re-entered that field, those within could not figure out how to operate it.

@@@@@ 71. jaimebabb

I don’t know how much individual intelligence would affect the progress of science; I think that it’s fundamentally a collective endeavour. I suppose that there may be some insights that could only come from the mind of such and such a genius,

I wasn’t positing a species with an average intelligence matching ours, but a higher proportion of geniuses. I was positing a species whose average intelligence was beyond that of our greatest geniuses. Naturally their cutting-edge science would be group efforts, dominated by what counts as genius on their terms.

@73/Fernhunter: “I was positing a species whose average intelligence was beyond that of our greatest geniuses.”

And I still say that doesn’t matter, because the laws of physics are the same either way. We don’t invent physics by being smart, we discover physics by observing how the universe actually works. So every species is eventually going to arrive at the same scientific discoveries and breakthroughs because they’re all living in the same universe.

I mean, if you put a person of average intelligence and a genius in the same house and they try to get out, they’re both going to find the same front door eventually. Because it’s a property of the house, not of their brains. The laws of physics are a property of the universe, not of the scientist. The whole point of the scientific method is to take the observer out of the equation as much as possible, to arrive at the truths that are the same for everyone. So it’s not about who’s looking. It’s about what there is for them to find.

@@@@@ 74. ChristopherLBennett

@@@@@73/Fernhunter: “I was positing a species whose average intelligence was beyond that of our greatest geniuses.”

And I still say that doesn’t matter, because the laws of physics are the same either way. We don’t invent physics by being smart, we discover physics by observing how the universe actually works. So every species is eventually going to arrive at the same scientific discoveries and breakthroughs because they’re all living in the same universe.

I mean, if you put a person of average intelligence and a genius in the same house and they try to get out, they’re both going to find the same front door eventually. Because it’s a property of the house, not of their brains. The laws of physics are a property of the universe, not of the scientist. The whole point of the scientific method is to take the observer out of the equation as much as possible, to arrive at the truths that are the same for everyone. So it’s not about who’s looking. It’s about what there is for them to find.

Christopher,

You have a lot more faith in the current success of our scientific understanding of the universe than I do. But okay. Posit, for the sake of argument, that you are right.

I still say it’s a plausible way to sneak FTL travel into some writer’s world building. We have no reason to suspend our disbelief that such bulge-brained BEMs haven’t spotted some way around the C limit that we have missed.

@75/Fernhunter: “You have a lot more faith in the current success of our scientific understanding of the universe than I do.”

I never said “current.” Why would that matter? Science is always learning more than it knew before. That’s literally what science is for.

And my whole point is that it’s not about us vs. them. It’s not about the person looking, because the laws of the universe do not change depending on who’s looking for them. That is the single most important principle of physics. It’s what the word “relativity” means in the first place.

“I still say it’s a plausible way to sneak FTL travel into some writer’s world building. We have no reason to suspend our disbelief that such bulge-brained BEMs haven’t spotted some way around the C limit that we have missed.”

As I already mentioned, that’s basically how the mechanism for warp drive and wormholes was achieved in my own primary SF universe. But that’s more about practice than theory. We already know the theory of how it would have to work. We’re already smart enough for that, and any smarter aliens would be working within the same theoretical framework, because it’s the same universe and the laws are not a matter of opinion. The problem is the engineering — there are huge obstacles to be surmounted, and it would take a lot of time and advancement before there’s any hope of finding a way to make it practical.

The point is that “the C limit” is not going to magically vanish if someone’s smart enough. New scientific discoveries don’t erase old truths, they just put them in a larger context. Einstein’s laws didn’t make Newton’s laws stop applying, they just established that Newton’s laws were a low-velocity approximation of Einstein’s laws. And when we finally have a theory of quantum gravity, it won’t make relativistic gravity suddenly stop working, it’ll just explain how it works in a more complete way. The speed of light will always be the law. And we already know that it can be circumvented through General Relativistic metrics that distort spacetime extremely enough. That question was answered by Einstein himself. The question is whether it can ever be physically practical to do it. And that’s not about some aliens being intrinsically smarter than us. It’s about how long they’ve been working on the problem. Because science always builds on what came before. It always comes closer to a full understanding. If there are smarter aliens out there, they may find the answers faster, but that doesn’t mean we won’t be able to find them at all, because those answers are built into the universe itself and we just have to keep looking until we find them.

@@@@@ 76. ChristopherLBennett

As I already mentioned, that’s basically how the mechanism for warp drive and wormholes was achieved in my own primary SF universe. But that’s more about practice than theory. We already know the theory of how it would have to work. We’re already smart enough for that, and any smarter aliens would be working within the same theoretical framework, because it’s the same universe and the laws are not a matter of opinion. The problem is the engineering — there are huge obstacles to be surmounted, and it would take a lot of time and advancement before there’s any hope of finding a way to make it practical.

The point is that “the C limit” is not going to magically vanish if someone’s smart enough. New scientific discoveries don’t erase old truths, they just put them in a larger context. Einstein’s laws didn’t make Newton’s laws stop applying, they just established that Newton’s laws were a low-velocity approximation of Einstein’s laws. And when we finally have a theory of quantum gravity, it won’t make relativistic gravity suddenly stop working, it’ll just explain how it works in a more complete way. The speed of light will always be the law. And we already know that it can be circumvented through General Relativistic metrics that distort spacetime extremely enough. That question was answered by Einstein himself. The question is whether it can ever be physically practical to do it. And that’s not about some aliens being intrinsically smarter than us. It’s about how long they’ve been working on the problem. Because science always builds on what came before. It always comes closer to a full understanding. If there are smarter aliens out there, they may find the answers faster, but that doesn’t mean we won’t be able to find them at all, because those answers are built into the universe itself and we just have to keep looking until we find them.

The physics of Einstein contain but transcend the physics of Newton. Try to explain modern astrophysics or quantum mechanics to a natural philosopher in the Age of Enlightenment and he will think you are crazy. Things are possible in the universe of relativity that are not possible in Newton’s billiard-ball universe.

Something similar may be true in the science of our brilliant BEMs. What? How? I haven’t a clue. Einstein et al leave me in their dust. Let alone entities who are by definition smarter than the best humanity has to offer.

Probably already mentioned but Cheddite is surely the answer. It was for Harry Harrison.

“Jerome Branch Corbell” – interesting tip of the hat to “James Branch Cabell”

Hadn’t seen that – found more at https://jamesbranchcabell.library.vcu.edu/cabells-writing/getting-started/

@26 Re: theory

This is what programmers call the duplicate identifier problem.

In science “theory” means what you describe. In general discourse “theory” is used interchangeably for what would be called in science a conjecture, a hypothesis, or a theory. The solution to the problem is what programmers call “scope,” the context in which the name has a given specific meaning. In language the scope of theory as a predictive model based on what we know now is science.

Smith’s “only a theory” is a gag.

@77/Fernhunter: ” Try to explain modern astrophysics or quantum mechanics to a natural philosopher in the Age of Enlightenment and he will think you are crazy.”

You make my case for me. A modern astrophysicist does not belong to a different, bigger-brained species than a philosopher in the Age of Enlightenment. Humans of both eras have the same level of intelligence, and so did humans 10,000 years ago. The difference in our understanding is not a factor of our innate intelligence, but of how much time we’ve had to apply that intelligence to learning how the universe works. Each generation has the same intelligence, but each generation goes farther because it builds on what the intelligence of previous generations produced. And every species that employs science is going to follow the same trajectory and eventually arrive at the same answers, because those answers are an intrinsic property of the universe regardless of who’s looking. It just may take longer for some than for others.

“Einstein et al leave me in their dust.”

Again you make my case for me. Any given sapient species will have a range of different intellects within it. It’s not a single quantity, but a bell curve, and the bell curves of different species would probably overlap quite a bit. So it’s questionable whether you could meaningfully define one species as “smarter” than another. Even if the average of the human bell curve may be lower than that of another species, the existence of exceptional individuals like Einstein shows that humans have the capacity to produce others with similar brilliance. So you can’t assume we wouldn’t be able to make the same breakthroughs as that other species.

Not to mention that even defining the concept of “more” or “less” intelligence is problematical and fraught with cultural bias. What one culture perceives as lower intelligence may just be a different kind of intelligence that specializes in different things.

I remember, many years ago, taking a SF class in college taught (in part) by science faculty, and I offered the claim (based on, among other sources, Martin Gardner’s Relativity for the Million) that any form of transportation in which you go to (say) Alpha Centauri (4+ light years away) and return, and for which the Earth records you having made the trip in less than the speed-of-light time, would break causality.

At least one of the science faculty couldn’t believe it. I brought in a book, he read the appropriate passage, and said that, well, he conceded that I had a printed source, but he still didn’t believe it. After reading through 80+ replies, I wonder if there aren’t quite a few of us SF fans who feel the same way!

My own thought is that wormholes and such like might be possible, but not to take us to other points in this universe; instead, they would take us to another universe. Each such wormhole would be the only way to get to that universe from ours, or (if there were more) they would have to be separated by the same distances in each universe (to forestall shortcuts). I have an idea for a novel based loosely on this idea, which I might get to writing, if I ever get around to finishing the last novel I started, which was so long ago that I, well, please nobody hold your breath.

ChristopherLBennett@74, by that argument dogs would have discovered space travel or at least invented can openers, but they never even tried because they never considered any such thing possible, nor imagined they might think of it. Something about human inteliigence, probably symbolic thought and language let you do things you just won’t ever think of otherwise. What’s to say there aren’t similar improvements to the mechanism of thought awaiting other species? In that case they might well be able to do things we’d never think of.

There is no guarantee we are the acme of intelligence, and no guarantee that we can think all thinkable thoughts, nor that thoughts in the human guise are the best form intelligence can take (it’s not like dogs have thoughts in the human guise: language again). It seems astonishingly unlikely to me, really.

It’s not just being a social animal or a tool user either: theory of mind isn’t that special. Crows have theory of mind and are tool users, probably about as good at it as australopithecines were. Hell, *chickens* have theory of mind.

Of course there’s that one story about the guy who keeps bugging the bureaucrats supposedly in charge of finding a way for man to reach the stars. He’s invented a hyperdrive that can put a vehicle into hypersphere. Finally the head of the bureau gives him a meeting, and reveals someone else invented his hyperdrive 20 years ago. He then reveals that the young hotshot has been making an assumption about the speed of light in hyperspace.

ChristopherLBennett@81:

It’s probably economics as much as anything — theories like this require both enough productive excess to have a lot of people whose main job is basically thinking very hard about things, and also the technological nous and excess productive capacity to carry out really rather expensive experiments. Medieval mankind, let alone, say, pre-Egyptian civilization, could never have come up with anything like the standard model or general relativity even if they’d endured for a hundred thousand years — not and have any evidence it was true, at least. The most they could do is come up with something with a few general features in common more or less by sheer luck, like Democritus did.

And I still say that doesn’t matter, because the laws of physics are the same either way.

They are?

we discover physics by observing how the universe actually works.

We do?

because they’re all living in the same universe.

We are?

Read a lot of comments and I agree with most of the physics, but most of the discussion is centered on a single dimension or universe. Say, there’s a multiverse instance that is practically identical to the instance you are in, but realigned so your destination is much physically closer to you. Insert mcguffin technology that transports you to new dimension. Said mcguffin could “calculate” or identify the desired dimension prior to travel. No relativity involved. Ala, Star Wars’ jump to light speed. Just not technically involving speed or light.

@83/Nick Alcock: “ChristopherLBennett@74, by that argument dogs would have discovered space travel or at least invented can openers”

That is a complete, specious misreading of my argument. I’m referring to species with the capability of employing science to learn about the universe. It should therefore be obvious that I’m not talking about dogs.

Also, inventing can openers requires opposable thumbs. It’s invalid to equate technological capability with mental capacity. Dolphins are probably smarter than we are, but you try starting a campfire underwater with a pair of flippers.

“What’s to say there aren’t similar improvements to the mechanism of thought awaiting other species?”

I never said there couldn’t be. I said there’s no reason to assume it requires such advances in thought to solve problems such as FTL travel. Humans have solved many scientific problems that seemed insoluble to earlier generations, so there’s no reason to assume we can’t solve FTL or whatever with our current level of intelligence, even if it takes thousands of years to reach that point.

@85/Nick Alcock: “Medieval mankind, let alone, say, pre-Egyptian civilization, could never have come up with anything like the standard model or general relativity even if they’d endured for a hundred thousand years — not and have any evidence it was true, at least. The most they could do is come up with something with a few general features in common more or less by sheer luck, like Democritus did.”

That’s because they didn’t have the Scientific Method yet. Once we had that, our pace of discovery accelerated exponentially. We didn’t have to get bigger brains; we just needed to come up with a better way of finding things out. Most importantly, we needed to understand that we should change our views to fit the evidence instead of only believing the evidence that fits our views.

This is the gist of my cover story in the current Analog, “Aleyara’s Descent.” It’s basically a story of how an alien civilization arrived at the Scientific Method at a much earlier point in their history. Imagine how much more rapidly we would’ve advanced if we’d done so as well.

@88, That about the scientific method is spot on. I have first proponents of exactly that here in my vicinity. Father and son Fabricius. Father discovered the first Western supernova in 1604. Son discovered sunspots in 1611. Both discoveries are against the belief that all in heaven is eternal, thus stars ought not to change.

While father took his supernova for real, he was adamant that sunspots are atmospheric. The sun must be perfect as it forms the center of the universe. Son was convinced that sun rotates around itself in roughly a month, which father also refused to take for real.

Son then wrote “De maculis in Sole observatis”, a treatise that also has a chapter saying that one must believe one’s eyes, not books. True insight is only gained and valid when obtained by senses or trying out, thus experimenting. That pretty much predates Descartes, and son Fabricius studied at Leiden, one hotspot for developing the philosophic foundations of the scientific method. He must have picked up a lot of that spirit there, while his father was still stuck in former lines of reasoning.

We can here directly observe the disrupting way thought changed at the end of the 16th century and which paved the way for Descartes and Newton. Without that, our world would not have gotten steam engines and the Energy that enabled progress by freeing more and more heads from labour to engage in Schiene and technology.

Newton by the way did not discover gravity. He realized that whar makes the apple fall is the same force keeping celestial objects in their orbits and explains all three Kepler laws. Heaven and earth are physically equal, thus enabling us to transfer knowledge gained there to here and vice versa. That is the beginning of how astronomy and high energy physics are so closely intertwined today, hoping for the grand unified theory. Between that lie Thermodynamics, Maxwell, Relativity and Quantum Theory, foundations of all our technology.

Which reminds me that I always wanted to do a proper translation of son Fabricius’ treatise aß there is none yet. I did a rough sketch only for a Talk I once Held.

I’m referring to species with the capability of employing science to learn about the universe. It should therefore be obvious that I’m not talking about dogs.

You seem highly confident that humans aren’t the equivalent of dogs, galactically speaking.

To be specific: Ansibles would propagate information faster than light, which is what relativity rules out. Furthermore, the very concept of the ansible assumes that there is such a thing as (absolute) simultaneity, whereas relativity requires that two events can be simultaneous in one frame of reference while being non-simultaneous in another.

@90/sibley: “You seem highly confident that humans aren’t the equivalent of dogs, galactically speaking.”

Everything is relative. One more time: I am not addressing the question of whether higher intelligences exist. I am saying, specifically and exclusively, that I do not see any reason to assume that higher intelligence than ours is required to solve new physics problems. We’ve done pretty well so far at achieving things that our ancestors a century or three ago would have considered beyond the realm of possibility. We’ve harnessed the power of lightning, achieved flight, learned to engineer the essence of life, and set foot on the Moon. Our ancestors would have thought us gods that we could do all that. But we are no more intelligent than they were; we’ve just had more time to work our way up to these things. So let’s not assume we’ll never be able to solve a problem just because we haven’t solved it yet.

Poul Anderson again, the master of using the constraints of physics to structure a plot; “Time Lag,” a tale of interstellar conquerors who make a mistake.

Just wondering under what umbrella would McCaffrey’s “Talents” fit? They communicate telepathically across space and use generator-boosted telekinesis to toss and catch transport containers across the vast distances of space.

Well, suspension of disbelief does have limits. I’m willing to temporarily believe that Westeros could exist and fire-breathing dragons could exist there. I’m not willing to believe that Westeros has Starbucks franchises.

97: Westeros shares some cultural referents with Martin’s Thousand Worlds. If Westeros is just a lost colony world settled by the Federal Empire before the Thousand Year War with the Fyndii and the Hrangans, and all the magic and such is just alien psionics and high tech, then other terrestrial relics may remain.

@38: James Williams

From True Grit (2010):

Mattie Ross: Why did they hang him so high?

Rooster Cogburn: I do not know. Possibly in the belief it’d make him more dead.

Ah, James Nicoll’s Law is still valid, I see.

Ken MacLeod has used various approaches. Wormholes in Newton’s Wake and I think the Cassini Division; “what FTL?” in Learning the World (immortality and electromagnetic catapults instead); and perhaps most charmingly, simple light-speed teleportation in the Engines of Light series, sidestepping the causality problems of FTL and the energy demands of NAFAL. True, there is no plausible mechanism, but at least it’s less trivial to point to a conservation law that’s being violated.

Alastair Reynolds mostly avoided use of FTL, but the Inhibitor universe did have it. Sadly, the immediate causality violations were so creepy that the survivors declined to try to use it further.

Neptune’s Brood is Stross’s hard SF interstellar setting. More advanced robots from Saturn’s Children, usually ‘traveling’ by data transmission. The ending pushes out from hard SF but still avoids FTL.

I really enjoyed reading this thread, and CLBennett I’m going to check out the Hub (hopefully no TSA drones will mess with my trip!) after I finish the new Agent Pendergast novel, The Cabinet of Dr. Leng. Got hooked on Agent A. X. L. Pendergast with Relic & Reliquary, can’t seem to quit. My comments, in no particular order- I loved the Grey Lensman series, and pretty much all E. E. “Doc” Smith. The author of the article didn’t seem impressed by his literary skill, but I discovered him at 9yoa, the same year my sci-fi nut Gramma took me to the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey. I had also just graduated from Poe to Lovecraft, and those ionic purple glowing iron bars and massive power tubes were pretty much described in Lovecraftian adjectival excess- and left enough of an impression on me that at 63yoa, I remove the covers from my McIntosh and Dynaco audio gear simply to meditate on the glowing tubes. Peaceful as fish given the right music. I’m torn by the warp drive/wormhole thing, and hopeful that the Alcubierrre method might work. And in my head, when I read “gates” in a story, I imagine manufactured and controlled wormholes. I remember the Einstein’s just a theory line, have that 60s published paperback here somewhere, and I’m annoyed that schools don’t seem to teach general students the scientific method. I bought a Tshirt that states: “When you say it’s just a theory, I hear I don’t understand how science works”. I’ve been given a lot to look into and read, here, thanks! The last footnote mentioned stealth in space. I think Mike Z Williamson had some good ideas in a short story set in his Freehold universe (10/10, highly recommend to political & military SF fans) called “Hate in the Darkness”. Hate was the nickname of a cruiser type starship, being used for an attack by the colonists of Graine (Gran-ya)- mostly Gaelic freeholders resisting being absorbed by the future UN- on a UN shipyard orbiting Saturn (iirc). The freeholders had figured out how to create their own gates with larger ships, the UN forces could only use pre existing gates in fixed positions. Anyway, the Hate was gutted and outfitted to tow a missle decoy and a small, low albedo asteroid to use as a kinetic weapon on the UN shipyard, thereby delivering a KT type of event on the hapless UN military. The Hate was well thought out, stripped, augmented engines & fuel supply, coated in low albedo and radar absorbing coatings and fitted with a system to mist the hull with liquid helium to minimize the heat signature. Very precise navigation allowed for minimal course corrections, and the acceleration was accomplished out system, so the Hate, missle decoy, and main impactor could coast, silent running, if you will. My astronomy nerd friends assure me that this setup would be very hard to detect, particularly if the approach was from above or below the plane of the elliptic and designed to occult the fewest stars; basically, if you weren’t looking and didn’t know where to look, surprise! Williamson is exmilitary, and his strategy/tactics and character development is very believable. And other than the gates, there’s no super science. Nuclear impact and EMP missiles, railguns, lasers arm the ships, troops make due with gauss guns and good old chemical propellants. I recommend the Freehold series, very readable and the humans take precedence over the technology. Even in the future, war is hell. And if not perfect, the Hate seems very close to stealth in space.

Going back to EE ‘Doc’ Smith & his Skylark – when he started writing the story (w Lee Hawkins Garby) , Special Relativity was still pretty contentious even within the hard core physics community. But by the time it was serialised in Amazing Stories (1928), Einstein had long since been awarded the Nobel Prize & had become a cultural icon following Eddington’s confirmation of the predictions of the General Theory. So there was really no excuse for not even acknowledging relativity!

But what’s interesting to me is that despite having a PhD in chemistry, Smith says little about the ‘intraatomic’ energy that powers the ship, or the structure of the atom, beyond ‘electrons whizzing about’. Having said that, the same was true of Asimov who also had a degree in chemistry of course and who acknowledged that he didn’t understand quantum physics at all!

In regards to Chandler: the Mannschenn Drive “moved a ship forward in space while moving backwards in time”.

His Ehrenhaft drive, predecessor to the Mannschenn, turned the ship into a charged particle that moved along the lines of force connecting the stars.

101: Please consider the utility of paragraphs.

I had two unfortunate circumstances with Doc Smith: firstly, I encountered his fiction when I was a bit too old to be blind to its flaws, and secondly, thanks to the spotty book distribution of Disco Era Ontario, the first book of his I encountered was Gray Lensman, which is really better if one has read Galactic Patrol.

First, I find it bizarre that only two people in this thread mention physicist Miguel Alcubierre and his warp drive.

Secondly, I could go into detail on my feelings toward the negativity in this discussion, but instead i will refer you all (and compare most of you to) T. O’Conor Sloane, the 80’s-something retired distinguished scientist and editor of Amazing Stories. Go to Archive.org:

< https://archive.org/details/AmazingStoriesVolume02Number08 >

for the May 1929 issue, in which he comments in an editorial on p. 103 on how interplanetary travel is an impossible achievement that is mainly good for letting authors use it as a means of scientific speculation and storytelling, with the undertone that it amuses the readers and presumably keeps them buying the ‘zine and paying his salary. Apparently, this comments reflecting this attitude were expressed by him quite frequently

Has the memory of Arthur C. Clarke already faded from contemporary SF’s apallingly short attention span?

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.