James Frazer has a lot to answer for.

He was born in 1854 in Glasgow, Scotland. He became a Fellow of Classics at Trinity College, Cambridge. From there he leapfrogged sideways into folklore studies and comparative anthropology, two disciplines he knew nothing about (although to be fair, at the time, neither did anyone else really.) His masterwork was The Golden Bough, two volumes of meticulously researched albeit fairly wrong comparative mythology from all over the world. His research was conducted mostly by postal questionnaire since he wasn’t into travelling. The title of the book comes from one of the more mysterious bits of the Aeneid , where the Roman epic hero finds a magical golden branch which he then has to hand over to a priestess in exchange for passage to visit the land of the dead.

Frazer had some Complex Views About Religion. He basically decided that cultures moved through stages—starting with ‘primitive magic’, and then moving to organised religion, and finally arriving at science. How did he know what primitive magic was like? Well, he studied the beliefs of primitive peoples (by postal questionnaire, remember). How did he know they were primitive? Well, he was a Fellow of Classics at Trinity College and this was during the height of the British Empire, so practically everyone who wasn’t him was primitive. Convenient!

I’m not going to go into real depth here (like Frazer, I’m a classicist talking about stuff I don’t know that well; unlike Frazer, I’m not going to pretend to be an expert) but what you really need to know is people ate it up . Magic! Religion! Science! Sweeping statements about the development of human belief! Universal theories about What People Are Like! All wrapped up in lots of fascinating mythology. And he treated Christianity like it was just another belief system , which was pretty exciting and scandalous of him at the time. Freud mined his work for ideas; so did Jung—the birth of psychology as a discipline owes something to Frazer. T.S. Eliot’s most famous poems were influenced by The Golden Bough. It was a big deal.

But the main thing that is noticeable about the early-twentieth-century attitude to folklore, the post-Golden Bough attitude to folklore, is: it turns out you can just say stuff, and everyone will be into it as long as it sounds cool .

(Pause to add: I am not talking about the current state of the discipline, which is very much Serious and Worthy of Respect and therefore Not Hilarious, but about the joyous nonsense interspersed with serious scholarship which is where all the children’s folklore books my grandma had got their ideas.)

Take the Green Man.

Where does the Green Man mythos come from?

I’m so glad you asked. It comes from Lady Raglan’s article The Green Man in Church Architecture in the 1939 edition of “Folklore”, making this timeless figure out of pagan memory exactly eighty years old this year.

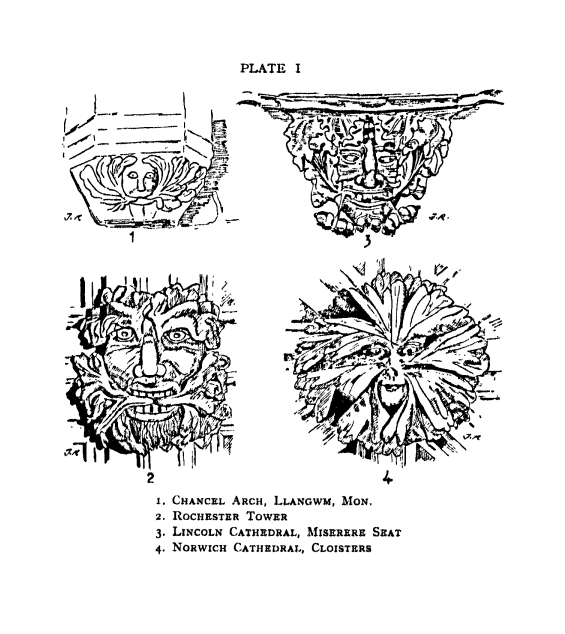

Lady Raglan made precisely one contribution to the field of folklore studies and this was it. She noticed a carving of a face formed out of entwined leaves in a church in Monmouthshire, and then found other examples in other churches all over England and Wales. She named the figure ‘the Green Man’. (Before that this motif in ecclesiastical decoration was usually called a foliate head, because it’s a head and it’s made out of foliage.) She identified different types of leaves—oak! That’s ‘significant’ according to Lady Raglan. Poison ivy! ‘Always a sacred herb.’

So: a human face made out of leaves, appearing in church after church. Could the sculptors have made it up because carving leaves is fun? Absolutely not, says Lady Raglan:

‘…the mediaeval sculptor [n]ever invented anything. He copied what he saw…

This figure, I am convinced, is neither a figment of the imagination nor a symbol, but is taken from real life, and the question is whether there was any figure in real life from which it could have been taken.’

You heard it here first: it is literally impossible for artists to imagine things.

Lady Raglan’s conclusion:

The answer, I think, is that there is only one of sufficient importance, the figure variously known as the Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, Robin Hood, the King of May, and the Garland…

Again I am not going to go into depth, so here’s the short version: this is kind of nonsense. There are like four separate traditions she’s conflating there. (To pick just one example: she’s talking about eleventh-century carvings, and Jack-in-the-Green—a traditional element of English May Day celebrations involving an extremely drunk person dressed up as a tree—is eighteenth-century at the earliest.)

The essential thesis of the Green Man myth is that the foliate head carvings you can find all over western Europe represent a survival . They are, supposedly, a remnant of ancient pre-Christian folklore and religion, hidden in plain sight, carved into the very fabric of the Christian churches that superseded the old ways. The Green Man is a nature spirit, a fertility god, a symbol of the great forests that once covered the land. He’s the wilderness. He’s the ancient and the strange. He’s what we’ve lost.

And here’s the Golden Bough of it all: this might be, historically speaking, dubious, but you can’t deny it sounds cool.

And you know what? It is cool.

Buy the Book

Silver in the Wood

As a folklorist, Lady Raglan’s historical research skills could have used some work. But as a myth-maker, a lover of stories, a fantasist , she was a genius and I will defend her against all comers. There is a reason the Green Man starts cropping up in twentieth-century fantasy almost at once. Tolkien liked it so much he used it twice—Tom Bombadil and Treebeard are both Green Man figures.

Lady Raglan might or might not have been right about pagan figures carved into churches. It is true that there are foliate heads in pre-Christian traditions; there’s Roman mosaics that show a leaf-crowned Bacchus, god of fertility and wildness. It is true that there are several European folk traditions of wild men, ‘hairy men’, people who belong to the uncultivated wilderness. But foliate heads are only one of several Weird Things Carved Into Churches, and no one has proposed that the grotesques and gargoyles (contemporaneous, show up in the Norman churches where foliate heads are most common, pretty weird-looking) are actually the remnants of pagan deities. Mermaid and siren carvings have not been assumed to represent a secret sea goddess. The pagan-deity hypothesis has been put forward about the Sheela na Gig, little female figures exposing their vulvas posted above the doors of—again—Norman churches, especially in Ireland. (What is it with the Normans?) But there are other explanations for all of these. Are they ugly figures to scare off demons? Abstract representations of concepts from Christian theology? Could it even be that Sometimes Artists Make Stuff Up?

Do we know?

No, we don’t.

And I’m not sure it matters.

The Green Man mythos—in its modern form, its syncretic form that pulls together half a dozen scattered and separate strands of folklore, many of them also dubiously historical—doesn’t have to be Real Authentic Definitely Pre-Christian Folklore to be a good concept, a good story, a good myth. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that our Green Man was born in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War. As Europe hurtled for the second time towards the nightmarish meat-grinder of industrialised warfare, it’s not surprising that Lady Raglan’s discovery—Lady Raglan’s creation—struck a chord.

Early folklorists—many of whom seem to have been basically just frustrated fantasy authors—were right about this: you can just say stuff, and everyone will be into it as long as it sounds cool. Which is to say, as long as it sounds right , and meaningful , and important : because a myth is a story that rings with echoes like the peal of a church bell. And by that metric the Green Man is as authentic as any myth as can be. The story almost tells itself. It says: he’s still here. The spirit of ancient woodlands, the enormous quiet of a different, wilder, less terrible world. You can see him lurking in the church; you might glimpse him striding through the forest. He is strange and strong and leaf-crowned. The fearsome forces of civilisation might try to bury him, but his roots are deep, and he will not die.

He is a mystery, but he has not left us yet.

Originally published June 2019.

Emily Tesh is the author of the Greenhollow Duology, which begins with Silver in the Wood and concludes with Drowned Country. Tesh is a winner of the Astounding Award and of the World Fantasy Award for Best Novella. Some Desperate Glory is her first novel.

Interesting article. Luv the capitalization :) . . . getting Milne vibes :).

Texas Tech University has carved on a column something that reminds me of a Green Man. I’ve got a pic but not sure about posting here…let me know if that’s possible. I don’t know when the columns were carved (tho’ I should!)

Goodness, I’m glad I found this piece, all these years later!

It made me laugh, and it’s just wonderful stuff. I was so certain the Green Man was an ancient thing. It goes to show…

If you are trying to claim that these figures do not go back to pre-Christian folklore, you might have picked better examples than gargoyles and mermaids. Plenty of gargoyles draw on imagery that long pre-dates Christianity and sirens are older than writing.

Based on the pace that stories evolve, we should pretty much always assume that something is a reference to already existing motifs. That’s how artists create today. Even if the exact form of the foliated head was new, the audience must have recognized something in it. Especially if it starts appearing in many places almost simultaneously. That suggests that it was readily and accepted by the audience, something that they already had a place for in their stories. Rather than our null hypothesis being “this thing appeared out of nowhere,” (pretty rare in human history, I think) our null hypothesis should be, “This most likely pre-existed this first example of it we can find,” just as Lady Raglan suggests.

Is it a secret god? That might be a stretch. Does it almost definitely hark to something? Well, if all of the gargoyles and sirens are any indication, probably.

That said, I have to say the foliated heads generally give me the impression of walking through the woods, turning about, and suddenly realizing that somebody has managed to creep very close to you and is now smiling at you through the brush. You get freaked out for a moment before you realize that the face is just a funny pattern in some bark, and then you have a little laugh at yourself. In a society still surrounded by wilderness, but growing more and more town-centered, maybe that experience is all the connection the foliated man needed to become popular?

But even then, just like the lure of the sea, you’re talking about an experience that humans would have had going back to the oldest times. There were probably many gods of forest peekaboo in pagan times.

“She identified different types of leaves—oak! That’s ‘significant’ according to Lady Raglan. Poison ivy! ‘Always a sacred herb.’”

I rather doubt she did, because she was looking at churches in England and Wales, where we don’t have poison ivy and never have.

The architectural gargoyle takes it’s name from the Gargouille of French legend, which has parallels in the Graouille and Tarasque folklore. Archeologist Isidore Gilles suggested a pagan origin for these monsters connected to the chimeric Tarasque de Noves statue.

The 19th and early 20th centuries were rife with ideas that propagated far and wide because they sounded cool, meaningful, fun, inspirational, daring or otherwise memorable, including (since you mentioned Freud) psychoanalysis, New Thought, theosophy, the Prosperity Gospel, positive thinking, etc. The fact that they were based on highly questionable or even outright wrong premises did nothing to stop their spread, because we humans love to parrot anything that has that combination of cool and memorable. Usually, after a couple of generations, the former cool factor becomes unfashionable and the meme dies out beyond the population of aging academic experts who have based their entire careers upon its supposed truth. Having T. S. Eliot’s endorsement certainly helps keep your meme alive much longer.

Think of today’s fashionable beliefs and our popular memes and you can readily see that the future may treat them less charitably. As Doris Lessing said, “Anyone who reads history at all knows that the passionate and powerful convictions of one century usually seem absurd, extraordinary, to the next. There is no epoch in history that seems to us as it must have to the people who lived through it. What we live through, in any age, is the effect on us of mass emotions and of social conditions from which it is almost impossible to detach ourselves. And yet, inside a year, five years, a decade, five decades, people will be asking, ‘How could they have believed that?'”

Woodwoses (or hairy wild men) do have a genuine mediaeval pedigree, however – they show up in manuscripts from that period, and possibly one could argue even earlier – Grendel might have been a progenitor. The name is originally Anglo-Saxon, so the myth is pretty old. They are apparently featured as bas-reliefs on some early English churches.

If you want an example of a 20th-Century farrago of early myths that doesn’t necessarily have much real basis in reality but got picked up and promoted as depicting genuine survivals from the pre-Christian European past, try Robert Graves’s The White Goddess.

Incidentally, I took The Golden Bough with me as reading material on a long field season. When you’re reading it in a wild landscape and don’t have much contact with other people, it resonates.

Also, 3 makes a good point.

I mean, what’s the argument here? Christian art and mythology contains no repurposed pre-Christian elements? Plainly that’s wrong. So what’s wrong with thinking that foliate heads might be another example? Given that (as you didn’t mention) we have actual examples of pre Christian gods being depicted as foliate heads?

No expert! Only Love can save us now!

This dome of once happy gases we depend on, live under, and continue to foul, Will kill us, if we don’t find ways, immediately, to staunch the fouling.

If we continue to think, head-in-sand, as a Whole, we tend to; no one/being coming from our outside/ wild or off planet fantasies will be able to help us.

The planet, as a Whole, must pull itself up by throat, hair, collar, boot strap, or whatever means clear thinking and nearly exhausted Reason can muster under these deadly illusions, like nationalism and Once pride of place, we keepers of the domicile have told ourselves were so important.

Next to survival of Life as we Know It, they Are Not.

My older brother used to be in the “Green Man Running Club”, based in London. I once or twice ran for them in races. I think the origin of the name came from their appearance when badly hung over, rather than any folklore reference.

@3 and 8, I think the hilarious thing about this quote ‘…the mediaeval sculptor [n]ever invented anything. He copied what he saw…” is the implication that a lack of imagination was a trait specific to sculptors of the medieval era but apparently not sculptors from other time periods. Even leaving aside the point of whether living in the medieval age stunted your creativity, it seems like quite an extrapolation to assume the inspiration had to be some mythological figure. Maybe their best friend decided to scare them by poking their head out of some bushes one day, and a sculptor was like, “Hey, that would make a cool carving,” and then it spread like a meme.

“and then it spread like a meme”… you mean, lots of other mediaeval sculptors saw it, and then copied what they saw?