In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

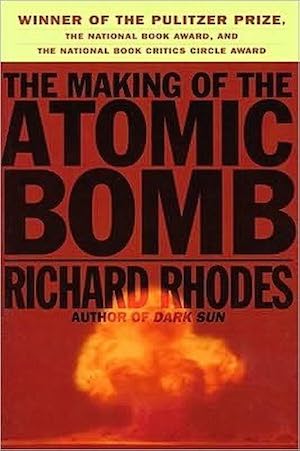

The ads for the new Christopher Nolan movie Oppenheimer had me thinking about the Manhattan Project, one of history’s most significant and controversial technological achievements. That, in turn, called to mind one of my favorite books of all time, The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes. Every science fiction fan has non-fiction books that influence their thinking, and this is one of mine. Fiction is full of stories of individuals cobbling together new technology all on their own, but the reality is very different. Technological advances are usually due to the collective effort of many people, and this book is an excellent overview of how science theory becomes science fact. Moreover, it is also an important meditation on the ethics of technological advances, which can often bring dangers that outweigh their benefits.

The copy of the book I read for this review is the Touchstone trade paperback edition issued in 1988. It is a massive volume, nearly two inches thick, and weighing in at over two pounds. It started to pull itself apart as I read, the weight of the book being too much for the decades-old glue that held the spine together. When I decided to write about the book, because of its size, I thought that instead of a full reread, this time I might settle for “re-skimming” the book. But it is a testament to its quality that I read every word, despite all the distractions of summer happening around me.

In my youth, during the height of the Cold War, I was haunted and fascinated by the threat of nuclear war. The writers of both fiction and non-fiction in that era fed that fascination with tales of such a war and its aftermath, many of which I have reviewed in this column, including: Alas, Babylon, Damnation Alley, Heiro’s Journey, A Canticle for Leibowitz, The Long Tomorrow, and Armageddon Blues. The possibility of a war between nuclear powers felt very close, and I even got an aircraft identification guide so I would know if the planes I saw flying over my house were Soviet bombers (and have a chance to hide).

So, when I found The Making of the Atomic Bomb in a bookstore, I immediately bought it, and was captivated. No book I had ever read did such a good job of capturing the grand sweep of that program, and of making the intricacies of nuclear physics clear to the lay reader. It had a profound effect on my thinking regarding the topic of nuclear weapons. A few years ago, I reviewed Willy Ley’s book on the early space program, Rockets, Missiles, & Space Travel, and the comments indicated that a number of other science fiction readers recalled key non-fiction books that inspired their imaginations, especially when those books had first been encountered when they were young.

About the Author

Richard Rhodes (born 1937) is a journalist, historian, and author of both non-fiction and fiction. He had written several books before he received national attention with the 1986 publication of The Making of the Atomic Bomb, a book which won a Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and a National Book Critics Circle Award. Rhodes has written biographies and history books on a wide variety of topics. He has also written many magazine articles, a play, and works of fiction, including four novels. The success of The Making of the Atomic Bomb led him to write a number of other books on topics related to nuclear weapons and energy, perhaps most notably Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Rhodes was recently interviewed for the MSNBC special program To End All War: Oppenheimer and the Atomic Bomb, which aired earlier this month.

The Making of the Atomic Bomb

The book opens by introducing us to Leo Szilard, a lesser-known scientist who played an important role in the process. He was a bright Hungarian physicist who had impressed Einstein during his studies, and was now contemplating how bombardment of an atom with neutrons could lead to the release of other neutrons. Szilard then had an epiphany: the release of neutrons might bombard additional atoms, causing a chain reaction, which could also release energy. Rhodes establishes a pattern with this first chapter, using detailed descriptions of persons, places, and things to draw the reader in. And by delving deeply into the experiences of an individual person’s life, he gives us insight into their studies and discoveries, and also the political framework in which they lived. It is a format that makes the history being presented feel more vivid, immediate, and personal.

The narrative then shifts to the concept of atoms, and the pioneering work of New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford, whose work expanded contemporary thinking on sub-atomic particles and how atoms were constructed. As his story unfolds, the names of other scientists come fast and furious. Some of these will be revisited later in more detail, while some are just briefly mentioned in relation to an observation or discovery they might have made, or a device they might have invented. Through the eyes of Rutherford, we are introduced to the young Niels Bohr, the Danish scientist who would have a major impact on the world of physics. Bohr spent his career teasing out the nature of sub-atomic particles, and in doing so, built on pioneering work by Max Planck and Albert Einstein.

We are next introduced to German scientist Otto Hahn, and the narrative steers into what seems to be a digression into German politics and the First World War. We are drawn into a description of the horrors of that war, with its machine guns, more accurate artillery, poison gas, and the first aerial bombings. But it turns out this is not merely a digression—international politics and methods of warfare were just as critical to the development of atomic weapons as the science that underpins that development.

The narrative follows the many Hungarian scientists that fled the communist revolution that followed World War I, followed by a fascist takeover, becoming the first nation in Europe to fall to what soon became a political epidemic. Szilard was one of these, as were Edward Teller and John von Neumann. A frail young Robert Oppenheimer enters the story, falling ill as a teenager and sent by his father to New Mexico in hopes the Western climate will toughen him up. Oppenheimer went on to study at Harvard and then moved on to Cambridge, but while he was seen as a brilliant student, he was unhappy with his studies and lab work there, eventually completing his PhD in Germany. During the interwar years, scientific ideas were emerging and developing at a rapid pace, with the findings of one scientist inspiring new possibilities and directions of thought in many others, an intellectual analog for the atomic chain reactions they were studying. The section describing this cascade of “eureka” moments was my favorite part of the book.

Rhodes introduces us to the machinery of physics and devices like mass spectrometers and particle accelerators. We meet more scientists, notably the German physicist Werner Heisenberg and Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. The rise of Hitler and the Nazis begins to impact politics in Europe. Because many of the best physicists of the time were Jewish, the anti-Semitic actions of the emerging fascist governments resulted in a steady flight toward safe havens such as England and the United States (the irony of anti-Semitism strengthening the enemies of the fascists cannot be overstated). And in a major breakthrough, Niels Bohr found that an isotope of uranium, U-235 (not uranium itself), when bombarded with neutrons would split and, instead of releasing neutrons, would release energy. This was immediately seen as not only a source of power, but also a possible means of creating incredibly powerful explosions.

As war was breaking out in Europe, scientists in America began to consider voluntary secrecy, not publishing some of their findings, and approaching the government to suggest more research on the topic. With so many fleeing the Nazis, and with Germany long having been a center for physics and engineering, many scientists were terrified by the idea of Adolph Hitler gaining and wielding the power of atomic weapons. The politically minded Leo Szilard was central in this effort, which culminated in a famous letter from Albert Einstein to President Roosevelt. And after a few bureaucratic hiccups and delays, objections were swept aside as World War II exploded across Europe, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and the US fully committed to an effort to build the atomic bomb. On December 2, 1942, an effort led by Enrico Fermi (who had left fascist Italy for America), using a lattice of uranium and graphite bricks, pulled neutron-absorbing control rods from the device, and the first atomic chain reaction was initiated. Scientists also discovered that neutron bombardment could transmute uranium into a new element, plutonium, which could be split like uranium and thus was another candidate for bomb production.

Rhodes describes how concerns about German efforts turned out to be overblown. The German project had mistakenly decided that graphite was not a good material for moderating reactions, and they put their focus on “heavy water,” a substance in which the hydrogen atoms have an extra neutron attached. Commando and sabotage efforts by the Allies, though, kept the German scientists from using the heavy water they needed, and their efforts stalled out, especially after the Allies began to turn the tide of the war and carry the fight back to Europe. At the same time, while they were aware of the possibilities of fission, Japanese and Russian efforts never progressed beyond initial research.

Rhodes shows us how the Department of War was put in charge of the “Manhattan Project,” named after the location of its engineering headquarters. After some organizational shuffling, an Army Corps of Engineers general, Leslie Groves, was put in charge. He was the perfect man for the project, pugnacious and driven, with a good head for details. Many scientists were resistant to military leadership, but Groves won most of them over, and brought something they had never seen to the table: nearly limitless funding. One of the scientists working on research, Robert Oppenheimer, was picked to lead the team who would design and build the bomb. While he was a brooding and introspective character, he also impressed the scientists as one of the best minds in the room. He also had a way of managing people that many of his (often eccentric) counterparts lacked. The project needed an out-of-the-way place to build and test the bombs, and Oppenheimer’s youthful experience in New Mexico helped inform the site selection; their laboratory was built in Los Alamos. They figured that a weapon would need only a few kilograms of either U-235 or plutonium, and started work on how to bring that material into a critical mass and trigger the chain reaction.

However, Rhodes shows that the Los Alamos laboratory was just the tip of a giant iceberg. Separating U-235 from U-238, and creating plutonium, was easier said than done. Only tiny amounts had been isolated to date, and creating even small amounts of material required huge industrial plants that would be built from scratch to handle highly radioactive materials. That necessitated unprecedented levels of automation on the production lines, difficult in the days before computers and robotics. Two plants were built, one in Richland, Washington, and the other in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The task was daunting, as the chemical differences between the isotopes was miniscule. A range of procedures were tested and implemented, with a lot of trial and error along the way.

Buy the Book

Emergent Properties

Eventually, the narrative shifts back to Los Alamos. The bomb makers developed a gun mechanism that would shoot one subcritical mass into another to trigger the explosion. They also considered an implosion method of squeezing the bomb core into a critical mass. They initially abandoned the implosion mechanism until they found the gun mechanism only worked with uranium and not plutonium. So, they went back to the drawing board and came up with a workable implosion mechanism. They completed a uranium bomb they nicknamed Little Boy, which they felt confident could be deployed without testing. And they successfully tested an implosion-type plutonium bomb at their Trinity test site. Another plutonium bomb, nicknamed Fat Man, was prepared.

Rhodes describes the disappointment of the scientists as they learned that they would be given little voice in the decision over if, when, and how the bombs would be deployed, and the fact that the politicians making such decisions considered them naive. He also follows the selection of the bombing crews for the mission, the modification of their B-29s to handle the massive bombs, and the tactics they developed to escape after dropping the bombs. The narrative then shifts to the victims of these bombings, as Rhodes describes the impact of dropping Little Boy on Hiroshima and Fat Man on Nagasaki, first through eyewitness accounts, and then through scientific studies. If this section of the book doesn’t break your heart, nothing will. There follows an epilogue that gives some subsequent history of nuclear weapons and their impact on world politics. Written when the Cold War was at its height, the book is pessimistic about the possibilities of avoiding nuclear war without a turn away from nationalism.

The book is remarkably detailed, and does a great job making complex issues seem simple. It also brings to life the many people who were involved in designing, building, and deploying the atomic weapons, and does not flinch away from showing the horrible impact of their creations. In doing so, Rhodes shows that in science, while individuals are important, progress is often the result of collective effort.

Final Thoughts

Like many people, I’m looking forward to seeing the new movie Oppenheimer. But while I watch it, I will know that the focus of the movie is only the tip of the iceberg, just a small slice of the gigantic effort that produced atomic weapons. Those who want a better understanding of that effort, and how science becomes reality, should read The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Even though it was written almost forty years ago, it remains one of the best and most complete descriptions of the entire Manhattan Project and the scientific developments that led to it (the book didn’t win all those awards for nothing).

Now, if you’ve read The Making of the Atomic Bomb, I’d love to hear your thoughts. If you have recommendations on any other books on the Manhattan Project, or other non-fiction science books you have appreciated, I’d enjoy hearing those, as well. And if you want to comment on the new movie, I wouldn’t mind that either.

I read this a few decades ago and like the reviewer, found it to be a splendid book and impossible to put down.

Another fine history of scientific and engineering teamwork is Andrew Chaikin’s history of the Apollo program, A Man on the Moon. And I always think anyone interested in the early space program should read Michael Collins’ excellent Carrying the Fire.

I agree wholeheartedly. The Making of the Atomic Bomb is a tour de force at bringing to life a mind bogglingly large subject in a compelling and readable way. The scope is epic, the characterizations of the major (and minor) players engaging, and the pacing is perfection.

Required reading for anyone even remotely interested in the subject.

The funny thing is, I’ve read Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb, but The Making of the Atomic Bomb is still sitting on my (virtual Kindle) shelf. I do need to read that, and I know it will be fantastic, as the other book was.

I hardly need mention that anyone with any interest whatsoever in nuclear weapons and what they do has a copy of Glasstone’s The Effects of Nuclear Weapons on zeir shelf. Comes complete with cool circular Nuclear Effects sliderule! Want to know the depth of that crater that used to be New York City in Fail Safe? Dial it in (the film gives all the specs for the drop)!

I’ll just add to the chorus of praise. When you mentioned planning to just skim the book, I knew the next phrase was going to be that you reread it. Aside from producing a definitive history, as its size indicates, Richard Rhodes is that rare writer who makes non-fiction read like a novel. I’ve read many of his books since. “Dark Sun”, continuing the story of the hydrogen bomb, and Oppenheimer’s battles with Edward Teller and others, his later books on nuclear policy, which do get more polemical, justifiably, I think, and his Hedy Lamarr biography. I’ve never tried his fiction, and this article is piquing my interest to finally do so, and see if his novels read like a novel!

@3 You definitely need to read The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Dark Sun was a good history, but never felt as compelling as the previous book.

Nothing new to add; I just want to agree, The Making of the Atomic Bomb is a great book.

“Alsos” by Samuel Goudsmit is a good companion to Rhodes. It’s written by a man who was rather unique – he was a refugee top-level nuclear physicist in the US during the war who wasn’t part of the Manhattan Project, and was therefore picked as the head scientist of the Alsos Mission, whose job was to go into recently-liberated bits of Europe and find out just how far the Germans had got with their bomb project. Because he didn’t know anything about the Manhattan Project, you see, he could be safely put in situations where he was likely to be captured by the Germans. He knew there was an Allied bomb project, but that was about it. The Germans couldn’t have tortured anything useful out of him.

It’s a very personal account, and hard reading at times – the men Goudsmit is tracking down were his pre-war colleagues, and in some cases people he had respected hugely. And Goudsmit was Dutch Jewish, and while he had made it out, his parents had not, and the Germans murdered them in a camp. He discovers this when the Allies liberate Amsterdam.

But the line that sticks with me is from very late in the war in Europe, when Alsos has made it to Haigerloch in southern Germany and found Heisenberg’s failed attempt to build an atomic pile, still far from completion. Mission accomplished for Alsos, and of course a huge relief for Goudsmit and everyone else in the team.

And Goudsmit says to Boris Pash, his military counterpart, something to the effect of “this is wonderful, now we know the Germans don’t have a bomb, so we won’t have to use ours.” Because the whole point of the Manhattan Project was that the Germans were building a bomb and so the Allies needed one too, as a deterrent. It wasn’t originally intended for use against Japan; Germany was always the threat.

And Pash looks at him and says “Sam, you realise that if we build this thing, we’re going to use it.”

I pulled my copy of this book out of a storage box a few weeks ago in the lead-up to the release of the movie. It has been years since I have the book and it is on my stack of books to read this year.

I highly recommend Emily Strasser’s podcast The Bomb, produced for the BBC. Season one focuses on Szilard. Rhode’s book was surely an important source.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p08llv8n/episodes/download

or

https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/the-bomb/id1524778767

I have that edition of the book on my shelf. I think th more recent editions leave out the epilogue because its material is now in Making of the Hydrogen Bomb.

Slight correction: U-235 (as well as U-238) is “Uranium itself.” The number represents a specific arrangement of particles in the nucleus, but only the number of protons defines the element. Any atom with with 92 protons is uranium. U-235 and U-238 are uranium with different numbers of neutrons (hence the difficulty in isotope separation).

@12 Thanks. While I worked very hard to get the terminology right, it has been nearly 50 years since my last chemistry and physics classes.

Two non-fiction books about nuclear war that I happened to read more or less back to back as a kid were Herman Kahn’s Thinking About the Unthinkable and Tom Stonier’s Nuclear Disaster. On the whole, Stonier took an altogether more pessimistic view of the likely outcomes than Kahn.

Best Non-Fiction Ive red this year was Suzie Sheehys The atter of Everything. She is a exprimntal phycisist and she focusses on the experiments that led physics in the 20th century – and what practical use they gave. This is an apsect that is often neglected, since most popular physics books are written by theorists. I didnt realize for example (even if I should have) that hospitals have their own particle accelerators to produce unstable elements for screening or radiation treatment.

I read it years ago, I wish I could remember why I picked it up. Couldn’t put it down, although that was partially because I nodded off while reading it pretty routinely. But I don’t understand how, it was fascinating! The level of background on the players, Rhodes went back two generations to try and help me understand where the individuals were coming from. And that worked: they weren’t characters brought in to play their parts, it wasn’t just ‘these are things that happened in furtherance of this piece of history’, it was large numbers of complete and complicated people quietly doing what they believed needed to be done, despite intense concern about the ends to which they’re efforts could be used. Also, the whole segment on Feynman, now that was a character…

I was saving the hydrogen bomb sequel for the next time I had a real problem with insomnia, but it’s been a while now, it’s still sitting on my ‘to read’ pile, maybe I need to dive in.

Quite literally one of the best science, history, and political science books ever written. Along with its sequels Dark Sun and Arsenals of Folly, they are simply must-reads for basically everyone.

I just finished the book last week and agree entirely. A ripping tale, well told.

I found particularly interesting the final portions dealing with the factors leading to the use of the bombs; the Allied experiences with Japanese military tenacity, the widespread feeling that anything less than unconditional surrender could lead to a repeat of post WWI history, the realpolitik of the imminent entry of the USSR into the Pacific war, the estimated death toll of the planned invasion, the last-minute hardening of Japanese hawks, and finally, the intervention of Emperor Hirohito. A complex stew indeed.

Another good read for those interested in nuclear issues is The Curve Of Binding Energy by the always excellent John McPhee.

halyard@9: I agree that the podcast is very good; one rather wishes that Nolan has made his film about Szilard, but I suppose Oppy mad a more photogenic subject.

The Bomb could have used a bit of proofing (‘prooflistening’? what does one call that?) by the BBC, however. At one point one of the interviewees says that Pearl Harbor is on Hawai’i’s largest island (it’s not; it’s on O’ahu — though I suppose she could have been referring to population rather than physical size); and Strasser keeps referring to ‘Robert J Oppenheimer’, which is a bit annoying. Otherwise, though, it’s a great listen.

EDIT: ‘mad’ obviously should be ‘made’ but for the life of me I can’t get this editor to make the change; it insists on leaving it as is.