Living as we do in a golden age of speculative fiction, one in which avid readers may easily obtain works both ancient and new, in quantities so vast no living person could hope to read even the smallest fraction of what is available, it might seem difficult to imagine anything that might make all this even better. The answer: non-fiction about science fiction and fantasy! Even as far back as modern SF’s early days, when there was hardly any SF to write about, commentary on and about speculative fiction has been a thriving field.

Don’t believe me? Consider these ten works.

Modern Science Fiction: Its Meaning and Its Future, edited by Reginald Bretnor (1953)

Determined to establish that science fiction was a genre worthy of serious consideration, Bretnor assembled a coterie of experts to expound in essay form on their various specialties. Bretnor’s authors reveal wide-ranging interests beyond SF. Whether this collection accomplished its goal back in 1953, I could not say. However, the work provides an interesting snapshot of science fiction in 1953. I found Boucher’s history of SF publishing especially illuminating.

In Search of Wonder by Damon Knight (1956)

To quote from Knight’s Orbit 21, Knight believed passionately that “science fiction is a field of literature worth taking seriously, and that ordinary critical standards can be meaningfully applied to it: e.g., originality, sincerity, style, construction, logic, coherence, sanity, garden-variety grammar.” This volume collects reviews in which Knight applied those ordinary critical standards to the science fiction of the 1950s. The reviews are often scathing but are also extremely memorable.

The Issue at Hand: Studies in Contemporary Magazine Science Fiction by James Blish, writing as William Atheling, Jr. (1964)

Perhaps sensing frank reviews might not win him friends and allies amongst his colleagues, Blish opted to pursue much the same strategy as Knight under the pen name William Atheling, Jr. As acerbic as Knight, Blish did not refrain from reviewing his own work…or from panning it when he felt he failed to live up to proper critical standards.

The Way the Future Was by Frederik Pohl (1978)

The Futurians were a group of science fiction fans, many of whom became influential writers and editors (including Blish and Knight). Frederik Pohl (1919–2013) was arguably the most influential Futurian, shaping the genre in his roles as fan, agent, editor, and author. This memoir lays out Pohl’s good-natured perspective on science fiction publishing and his role in it, from the 1930s to the 1970s.1

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland by Diana Wynne Jones (1996)

Inspired by her efforts to help update The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, Jones provides a comprehensive tour of well-used clichés and absurdities beloved by authors who valued volume over verisimilitude and veracity. In its way, this book is as scathing as the work of Knight or Blish; however, Jones sweetens her text with ample humor.

Microworlds by Stanisław Lem (1986)

Being possessed of firm and specific views of what science fiction should be, Lem wrestles with the vast gap between science fiction’s potential and science fiction’s reality in this slender collection of essays. Lem reserves his most pointed ire for American science fiction. On the one hand, a cynic might wonder if Lem focused on the shortcomings of American SF because targeting well-connected Warsaw Pact authors might have been risky. On the other, Lem’s complaints are perfectly valid.

The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction by Justine Larbalestier (2002)

Battle is an exploration of women and feminism in science fiction. While the subject matter could fill multiple volumes, Larbalestier’s one-volume study is impressively wide-ranging, focusing on specific events and grand themes from the early days of SF to the modern era. Her study is sometimes depressing (have things improved or merely changed?), informative, and entertaining. I’d love to see an updated edition (hint, hint).

Better to Have Loved: The Life of Judith Merril by Judith Merril & Emily Pohl-Weary (2002)

Better to Have Loved is the posthumously published autobiography of noted writer/editor Judith Merril, as edited by her granddaughter, Emily Pohl-Weary. Another influential Futurian, Merril’s personal reminiscences cast invaluable light on science fiction’s development in a field Merril herself shaped as both an author and editor. Merril’s relentless work was of particular importance to her adopted nation, Canada.

Astounding by Alec Nevala-Lee (2018)

Astounding is an enthralling study of editor John W. Campbell, Jr. and the prominent figures in Campbell’s circle.2 For a number of reasons, not least of which was that he paid writers well and promptly, Campbell wielded influence to a degree no later editor has matched. For reasons detailed by Nevala-Lee—not least of which that Campbell was a racist crank—this influence was not an unparalleled good. Nevertheless, Campbell and his associates demand insightful examination, which Nevala-Lee graciously provides.

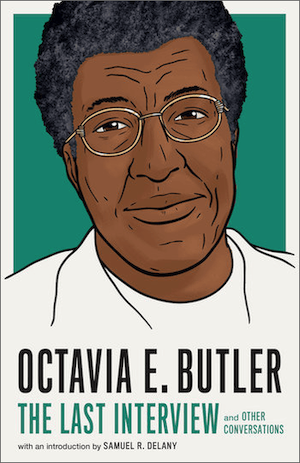

Octavia E. Butler: The Last Interview: and Other Conversations (2023)

[Note: I didn’t forget to include the name of the editor. As far as I can tell, the book specifies the publisher but not its curator; it also features an introduction by Samuel R. Delany.] This entry in the Last Interview series is not the final interview one might expect from the title. Instead, it delivers an assortment of interviews by a wide variety of interviewers, drawn from across Butler’s all-too-short career. Butler’s evolution as a writer is illuminated, as is the evolving society in which she worked.

***

This is only a very small assortment of non-fiction about science fiction and fantasy. No doubt. I’ve forgotten (or omitted due to my peculiar rules) many worthy examples. Feel free to discuss them in comments below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]Damon Knight offered a considerably crankier account of the Futurians in his text of the same name.

[2]One of whom, Isaac Asimov, is why I can’t snark that “not *every* book has to be about Futurians.” Asimov was, of course, also a Futurian. Futurians were everywhere. Perhaps one is hiding under your bed!

Two books by Jo Walton- What Makes This Book So Great? and An Informal History of the Hugo’s.

The Judith Merrill sounds fascinating.

And of course after sending this off, I happened across my copy of Panshin’s Heinlein in Dimension… Which is shelved next to Major’s Heinlein’s Children.

(The Science Fiction Encyclopedia got its own article, years ago)

1: Readers should of course buy those two books but they should also track down the original post series. The Hugo conversation, for example, is here.

In the course of tracking down the Hugo posts, I see Jo hit 500 tor dot com articles in just two and a half years, whereas this is, as far as I can tell, only my 424th piece and it has taken me six years to reach this point.

I love critical works about SF&F, I have a whole shelf of them! I expected you to mention Brian Aldiss’s two volumes: The Billion Year Spree and The Trillion Year Spree, subtitled The True History of Science Fiction. Mr. Aldiss is, of course, a bit of SF history in himself.

The non-fiction work that changed my thinking was Ursula Le Guin’s first book of essays on the topic, The Language of the Night, published in 1979. She published many essays about the topic since, and famously revised some of her thinking, but this initial volume opened up my mind. Her essay ‘From Elfland to Poughkeepsie’ demonstrated “This is what we point to when we want to point to fantasy”.

I have the Aldiss! But it is mass market non-fiction, and the A section of that is seven feet up. I am not saying I am too lazy to incline my head but …

On my shelf I have a hardcover of “The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of”, which I recall as being a bit grumpy. Probably should reread it someday, though I suspect it may not have aged well. Also a paperback of “The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction” purchased used sometime in the 90’s.

Is Kingsley Amis’ New Maps of Hell worth a read? I’ve had a copy for years, but never gotten around to it.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Astounding Days probably fits in here.

This is obscure beyond belief, but I recently read Constance Reid’s 1993 biography of British-American mathematician E. T. Bell (1883-1960), who also wrote a big handful of very early science-fiction/fantasy novels under the name John Taine. The book was primarily concerned with uncovering a fascinating but entirely unexplained mystery of Bell’s early life (why he concealed the fact that most of his childhood was spent in the United States), and after that his mathematical career, but every so often the reader would hear about Bell taking a month or two in a summer and firing off another novel. From Reid’s descriptions of these works, they seem to have been pretty all-over-the-place with respect to both topic and reception (and at least one looks like it needs a content-note about historical racism), but at the very least they sound interesting – and more so for having been well before genre conventions and tropes were nailed down.

See also Anthopology 101: Reflections, Inspections, and Dissections of SF Anthologies by Bud Webster. It is a collection of his essays and articles on the history and development of science fiction anthologies, of which he was a longtime collector.

Brian Ash’s Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, from 1978, is not really an encyclopedia, being rather a collection of heavily illustrated thematic essays, and although it has to be considered somewhat out of date by now, still goes highly recommended by me.

Ohhh, The Tough Guide to Fantasyland will be a great birthday present for my gf. She has many books of Diana Wynne Jones on her shelves, but not that one. I called up one of the local independent bookstores and ordered it. (I am weaning away from the giant online retailer.)

Camestros Felapton’s Debarkle covers the history of the Sad and Rabid puppies and the kerfuffle they tried so hard to cause as SF became more diverse during the second decade of the 21st Century.

Also very tongue in cheek, the Hugosauriad.

11: A problem with dead tree editions of encyclopedias is that as soon as they hit print, some momentous work of SFF will be published whose absence from the encyclopedia will look odd.

Could be worse: a few weeks ago I was flipping through my 1979 CRC Handbook of Physics and Chemistry, as one does, and I was struck by how out of date the astronomy section was, by the standards of 1979.

ENGINES OF THE NIGHT, Barry Malzberg.

(Haven’t read his later essay collection, BREAKFAST IN THE RUINS.)

@7 I’d say <i>The Dreams our Stuff is Made Of</i> is more than a bit grumpy; I suspect when he wrote it, Thomas Disch was well on his way to the frame of mind that resulted in his suicide (back around 2008, I believe). Still, while far from agreeing with his every judgement, I thought it a good and challenging overview from insider who hated most of the genre.

I’d add Algis Brudrys’ Benchmarks collections of his reviews from Galaxy and F&SF.

I love The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, but is it really best classified as nonfiction given the existence of Dark Lord of Derkholm/The Year of the Griffin?

Sam Lundwall’s Science Fiction: What It’s All About was an early 70s critique of the field from a European author. I read it back then and all I remember about it is him teeing off on Robert Heinlein.

19 I think books on SF back then had to tee off on RAH or at least mention him. Of course, these days they would have to explain who he was, first.

Colin Wilson’s book.

David Hartwell’s Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction. Hey, it’s Hartwell, what more can you ask?

Alexei and Cory Panshin’s The World Beyond the Hill: Science Fiction and the Quest for Transcendence. You like the Panshins’ work or you don’t. I do.

Asimov on Science Fiction by — awww, you guessed. A collection of pretty light essays, some of them on the grumpy side.

And — of course; how could I leave him out? — Chip Delany’s The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction; The American Shore: Meditations on a Tale of Science Fiction by Thomas M. Disch — “Angouleme”; and Starboard Wine: More Notes on the Language of Science Fiction. Much more technical stuff than I’ve seen listed here (especially The American Shore whose core is a practically word-by-word exploration of a single short story), but very worthwhile.

@8: Absolutely. It’s certainly of its time, and is highly opinionated (from Amis, one would expect nothing less) and often amusing, but it’s also written by someone who was very much a fan of SF. Most of his criticisms arise from his belief that SF can do a lot better. He holds Pohl up as someone whose work is to be admired. And in reference to the Nevala-Lee book, he hated Campbell.

@22: I haven’t read The American Shore but The Jewel-Hinged Jaw and Starboard Wine are absolutely worth the read.

Also technical but I have to include Darko Suvin’s Metamorphoses of Science Fiction; written from a very specific, Marxist viewpoint but still one of the major works in the field of SF criticism.

And the University of Illinois’s Modern Masters of Science Fiction series has produced a string of excellent books; I particularly recommend the Jed Smith books on John Brunner and Alfred Bester and Paul Kincaid’s studies of Iain M. Banks and Brian Aldiss.

An early example is L. Sprague de Camp’s Science-Fiction Handbook (1953).

It’s been so long since I read it I can’t actually describe it correctly.

@8) As Philrm says, New Maps of Hell is certainly worth reading.

My particular recommendation, perhaps my single favorite work of SF nonfiction, is Proceedings of the Institute for Twenty-First Century Studies, better known simply as PITFCS, edited by Theodore Cogswell. It’s a collection of the issues of a sort of “fanzine for writers”, and it is delicious. I reviewed it here: https://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2019/03/birthday-review-pitfcs-by-theodore-r.html

I also recommend Jo Walton’s Informal History of the Hugos, on merit but also for personal reasons.

I am making my way through the Merril Best SF annuals and ha ha did she hate New Maps of Hell. Didn’t stop her from publishing Amis, though.

Barnes. Linguistics and Language in Science Fiction-Fantasy (1975) spends IIRC a chapter per book of interest.

Two by Farah Mendlesohn:

The Pleasant Profession of Robert A. Heinlein is a very thorough examination of Heinlein’s work. It is thematic, so a bit repetitive, the same works show up under multiple themes. But it’s very thought-provoking, and Heinlein’s work holds up better than one might expect.

Rhetorics of Fantasy is a taxonomy of fantasy stories. It’s a bit long — if you are an experienced fantasy reader, you can read the first page a chapter and say “oh yeah, this”. But it’s very useful.

echoing @22: no delany? for shame.

The American Shore is indeed indispensable, but his wider-ranging pieces are great too, and when he dishes it’s the tasty stuff!

The best book ever is The Dictionary of Imaginary Places by Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi.

It is what it says on the tin, a traveller’s guide to imaginary places from Middle-Earth through Narnia and Oz to Llareggub and other more obscure locations, with wonderful illustrations and maps. A book to get lost in for hours on end.

Gothic Science Fiction 1980-2010, edited by Sara Wasson and Emily Alder. A bit specialised, but may well interest some.

“The Creation of Tomorrow” by Paul A. Carter was a terrific look at science fiction magazines from the Twenties to the Seventies.

It seems like there is a lot less non-fiction about fantasy, especially if you leave out the works which only discuss Tolkien.

33: There’s always On Thud and Blunder.…

Some personal favorites (that probably don’t stand up to close scrutiny):

Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds (which I think was was one of the earlier books to be written about primarily secondary world fantasy? And which included a couple of chapters of helpful(?) writing advice at the end).

L. Sprague de Camp’s Literary Swordsmen & Sorcerers — a series of brief (chapter-length) biographical essays about prominent fantasy writers including William Morris, Lord Dunsany and E.R. Eddison, plus more recent/contemporary folks (for values of “contemporary” for a book written only a couple years after Tolkien’s death).

The Blade of Conan/The Spell of Conan — A couple collections of essays & articles previously published in AMRA (the Robert E. Howard-focused fanzine) with, unexpectedly, a strong focus on Howard, but also touching on Burroughs and others, and including Poul Anderson’s article “On Thud & Blunder”, which is by itself worth the price of admission.

@30 – that book is good, but I think the maps and commentary on them is more interesting in J. B Post’s An Atlas of Fantasy.

This reminds me that Karen Wynn Fonstad did atlases for a number of fantasy worlds, but I didn’t read most of them and don’t remember what the ones I did read were like.

I really enjoyed the Hugo nominated

Becoming Superman: My Journey from Poverty to Hollywood.

by J Michael Straczynski

@35; I read and enjoyed de Camp’s original “Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers” articles when they were published in “Fantastic” in the 1970s – in most cases they were the first biographic information I had ever read on the featured authors. When I spotted a cheap copy of the Arkham House collection a few years back I bought it. That cop it is buried somewhere in the stacks, but from memory at least one of the original articles was missing – the one on L Ron Hubbard. I wondered whether that might have been due to representations from a certain organisation with which Hubbard was associated. I don’t think there were any scandalous accusations in the article, but its depiction of Hubbard as a competent jobbing pulp writer in the 1930s and ‘40s may have been at odds with said organisation’s view that the man was a titan of literature.

@32 – I’m rather fond of Mike Ashley’s multi-volume “History of the Science Fiction Magazines”.

@38 — Thanks! I didn’t realize the essays had been collected from magazine appearances, but that makes complete sense. And ha!, re: Hubbard.

@38 During his time as editor of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, Lin Carter also wrote Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings and Lovecraft: A Look Behind The Cthulhu Mythos. They were arguably the first mass-market, mainstream- published books on their subjects,but are now primarily of historical interest as they have long been superseded by better-researched works.

Brian Aldiss’ A Trillion Year Spree is a revision of A Billion Year Spree, not two volumes, I don’t think.

These are great recommendations. I can tell my to-read list is about to grow (again).

I have fond memories of A Reader’s Guide to Science Fiction (1979) by Searles, Last, Meacham, and Franklin. It helped me as a teen find new authors to read, back before we had the web (remember those dark days?) and also helped me articulate what I liked about what I was reading. In particular, I found the “if you like X you might also like Y” notes at the end of each author entry very helpful. Franklin, Searles and Meacham followed it up with A Reader’s Guide to Fantasy in 1982, which wasn’t quite the same format, but still helpful. All dated now, of course, but interesting snapshots of that point in SF/F history.

#18, I think The Tough Guide to Fantasyland is definitely non-fiction, and a great critique as well, despite its relationship to Dark Lord of Derkholm — the critique in fiction format.

Card has a book on writing SF/F (a couple of editions/versions) that is also interesting– concepts are illustrated with examples from a range of authors.

@38,

I remember hearing the De Camps talk about there being court cases/injunctions between them and Scientology/Hubbard.

Conan Meets the Academy is a collection of scholarly works- pretty readable, even for us non-scholars.

Don’t forget “All Our Yesterdays” by Mr. fanac himself Harry Warrer Jr. – the sage of Hagerstown.

I greatly enjoyed Gleick’s Time Travel: A History (2016), which explores both the cultural phenomenon of a new social perception of time, and the history of the subgenre.

I love books of essays more than formal histories though I have quite of few of those on my shelves too. As I’ve gotten older (more experienced?) I find I enjoy trading ABOUT science fiction as much as I enjoy reading science fiction. Mostly oldies but goodies…….

Science Fiction At Large, edited by Peter Nicholds

Dream Makers, by Charles Platt

Reflections and Refractions by Robert Silverberg

Hell’s Cartographers, edited by Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison (and what a great title!)

And for movies and such, Jar Jar Binks Must Die by Daniel Kimmel and 24 Frames into the Future by John Scalzi

Most recently, Lost Transmissions, edited by Desirina Boskovich

And I couldn’t pick one out of the eight books about PKD on my shelf.

@43 — Searles’ A Reader’s Guide to Fantasy directed me to some great authors.

I can’t believe I didn’t think of this earlier, but Brian Murphy’s recent Flame and Crimson, A History of Sword & Sorcery is very highly recommended to the sorts of people who want to read something that matches that title. (Like me.)

Also Robert E. Howard Changed My Life, edited by Jason Waltz. I haven’t read the actual book, but I read a number of the component essays when they first appeared on blackgate.com.

James Gunn’s Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction made a HUGE impression on me when I discovered it while in high school in the late 1970s. It changed my understanding of science fiction. What had been “far out books and movies and shows that I like” became an entire field with a history, themes, personalities, venues, sociology, and even politics. Before AW I’d been strolling down a hallway admiring a few specimens here and there under glass.AW sent me out the door into into the vibrant, living ecosystem of SF.

I have to mention:

– The Making of Star Trek by Stephen E. Whitfield and Gene Roddenberry.

– The World of Star Trek by David Gerrold.

It’s definitely on the academic and theoretical side of things, but Fredric Jameson’s _Archeologies.of the Future_ is incredibly thought- provoking. The first half is an extended essay on the utopian dimensions of SF as a genre, and the second half is a collection of his shorter essays on specific books over the years, with special focus on Le Guin and Kim Stanley Robinson (who was Jameson’s student).

Lovecraft: A Biography (1975) by L. Sprague de Camp is noteworthy in part for being released by a major mainstream publisher (Doubleday) and reviewed in mainstream press. At the time it was controversial for not being the hagiography many Lovecraft fans wanted, with de Camp pointing out many of Lovecraft’s personal biases that were often extreme even for his time. Nevertheless, one could argue that much Lovecraft scholarship since then has been in response to de Camp’s work.

@36: This is a very belated comment, but I own Karen Wynn Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle-Earth, as well as her Atlas of Pern and Atlas of the Land (from Stephen R. Donaldson’s Chronicle’s of Thomas Covenant), although not her atlases of Dragonlance or the Forgotten Realms. I remember being very impressed by The Atlas of Middle-Earth when I first encountered it; she had a very distinctive style of cartography, and her atlases include both describe the places involved (with notes on the geography and geology where possible), and track the characters’ journeys across the landscape.

Now, of course, there are probably hundreds of different maps of Middle-Earth and other fantasy realms available online, but at that time, in the early ’80s, such resources and the tools for creating and sharing them did not yet exist, so Karen Wynn Fonstad was something of a pioneer. It is a shame that her fantasy mapmaking career was cut short by cancer.