In Ray Bradbury’s short story “A Sound of Thunder,” a wealthy time travel tourist accidentally crushes a pre-historic butterfly beneath his shoe. This delicate, seemingly insignificant mistake ripples forward to create an entire alternate future. It’s a truth that extends far beyond fiction— how the smallest acts can bloat, twist, topple dominos that leave our world irrevocably changed. Like the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand as the catalyst for WWI. Or the World Trade Center attacks resulting in the Twilight franchise.

When ancient Etruscans served up the world’s very first bowl of pasta, they had no idea that humans would still be dining on the dish nearly twenty-three hundred years later. Nor could they have known that their simple meal would one day lead to the birth of one of history’s most feared and beloved monsters. In fact, a single humble noodle would go on to change the course of all of English literature.

We’ll start where it counts: 1816. The Year Without a Summer.

Far off in the East Indies, Mount Tambora had erupted—rocketing volcanic ash all the way to Europe. Great, strange clouds blocked the sun like a biblical plague and rain fell without respite. Cold tendrils of fog slithered up from the sea. Crops sickened, then died, leaving ordinary families to starve as their food stores dwindled low. And all the while, Percy, Mary, Claire, George, and John were partying like it was the end of the world.

Percy, of course, refers to Percy Bysshe Shelley—the famed Romantic poet known for such works as “Ozymandias” and “Ode to the West Wind.” He, his teenage mistress Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (later, Mary Shelley), and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont, had all followed Claire’s latest beau Lord George Gordon Byron to Geneva for the summer. The friends—oh so accurately referred to by the tabloids as “The League of Incest”—had rented a villa by the coast, hoping to spend the summer sailing and sunbathing. Byron’s twenty-three-year-old physician John William Polidori had saddled along for the ride, too. They were young. They were hot. They were ready to be seen. But the weather had other plans.

And so, the League found themselves trapped in their 19th century Airbnb, scowling out the windows. As Mary wrote to her half-sister, Fanny, “An almost perpetual rain confines us principally to the house… The thunder storms that visit us are grander and more terrific than I have ever seen before.”

It’s Gothic legend, by now: how the Romantics spent their days debating philosophy, making out, and reading German ghost stories aloud. Which, might I suggest, would make a compelling vacation package on Kayak.com. Then, one famed night, Byron proposed a little contest. Enough of simply reading horror stories. They were writers, after all! It was time to create their own. Yes, it was settled: each of the friends would write an original ghostly tale—and the most frightening would be crowned the winner.

As the others sank into chaise lounges, quills in hand, Mary faltered. Perhaps she scribbled a line. Crossed it out. Began again. Her companions’ pages filled with specters and vampires, but Mary’s stayed blank. In short—she just couldn’t think of a damn idea. But then again, she knew full well that she wasn’t the true talent in the group. That was a status reserved for Shelley and Byron, two of the greatest poets of their age. And so, Mary was resigned to lose the contest, contentedly eavesdropping on the men’s lofty conversations, instead—who, for their part, quickly grew bored of the competition, themselves.

“Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener,” Mary would later write. “During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. They talked of the experiments of Dr. [Erasmus] Darwin… who preserved a piece of vermicelli in a glass case, till by some extraordinary means it began to move with voluntary motion. Not thus, after all, would life be given. Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated […] and enduced with vital warmth.”

For those readers who, like me, do not have an intimate knowledge of every single pasta shape known to man: vermicelli is like spaghetti. It can be thicker or thinner than spaghetti depending on which country you ask, but essentially, we’re dealing with spaghetti. Also, to my great delight, the “vermicelli” Wikipedia page informs me that the word directly translates into, and I quote, “little worms.”

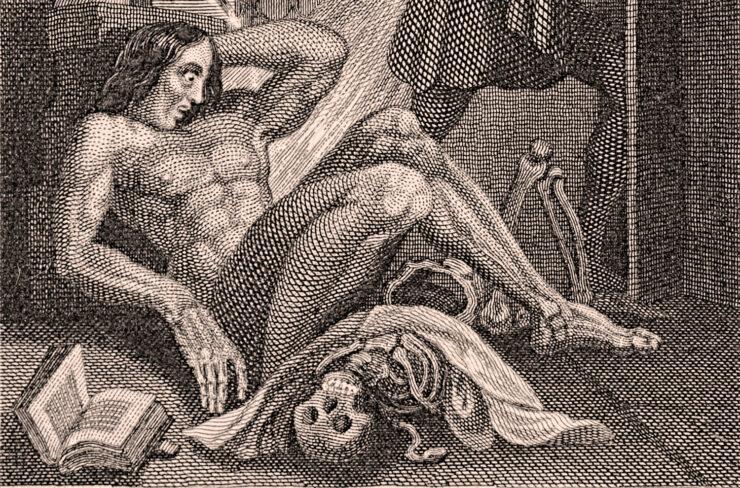

Later that night, on June 15th of 1816, Mary had a terrifying vision. She saw “the hideous phantasm of a man” stretched out on a slab—and then, not unlike Darwin’s vermicelli, a “powerful engine” stirred the body shudderingly to life.

In that single piece of pasta, Mary had found more than just her ghost story. She had stumbled upon the inspiration for her first novel—and with it, the very first science fiction story ever written. A harrowing tale called… Frankenstein.

But here’s the thing about Dr. Darwin’s writings. Nowhere in any of his works does he ever, for a moment, mention a piece of vermicelli pasta. Or any pasta for that matter.

And this, my friends, is where things begin to get very, very stupid.

Dr. Erasmus Darwin, born in 1731, was one of eighteenth-century England’s leading intellectuals and naturalists. He was grappling with questions of evolution generations before his grandson, Charles Darwin, would go on to develop the theory of evolution by natural selection. And listen, I have no explanation for this tidbit, but for whatever reason, grandpa Erasmus tended to write his scientific treatises in the form of rhyming couplets, riddled with erotic humor. Why the fuck not, right? Honestly, if academic papers were hornier and rhymed, we’d probably all be reading more of them.

Shelley and Byron would certainly have been familiar with his work—and they weren’t the only ones. Coleridge and Wordsworth, too, mention Darwin in their own writings, and he was a well-known name in English academic circles. But while Shelley and Byron had likely read Darwin, they may not have been exactly… understanding it.

Maybe it was the cheeky little sips of laudanum the friends shared in their storm-lashed chalet. Maybe it was the poets’ overwhelming cockiness and a lack of attention to detail. Whatever the case may be, Shelley and Byron made a fatal error in their comprehension of Dr. Darwin’s work. An error so unfathomably dumb, I couldn’t help but write an entire, gleeful essay about it.

See, while Darwin never mentioned vermicelli, he did write about a microorganism called vorticella.

“Thus the vorticella, or wheel animal,” Darwin wrote, “which is found in rain water that has stood some days in leaden gutters […] is capable of continuing alive for many months though kept in a dry state.”

Is it possible that, in a moment of blazing, legendary idiocy, bffs Percy and George mistook a reference to a microorganism for… a reference to pasta?

Absolutely. But there are other explanations too. Don’t worry though—they’re just as ludicrous.

In the same text, Darwin discusses an experiment—not even his own experiment, mind you, but someone else’s—in which well water is sealed in a glass bottle, and a green plant called “conferva fontinalis” is seen to grow. This accounts for the “glass case” referenced in the poets’ conversation—but where the hell would they have gotten vermicelli? Well, turns out, despite their misleading looks, “conferva fontinalis” and “vermicelli” actually… rhyme. And with that, the big ol’ game of pasta-themed telephone strikes again.

Now, there’s one final theory for our pasta imposter’s origin, in which Darwin talks about creating a paste of water and flour in which tiny living beings appear to grow “in great abundance.” He later concludes: “even the organic particles of dead animals may, when exposed to a due degree of warmth and moisture, regain some degree of vitality.” This one is a little closer to a pasta-like recipe—and does include the idea of reanimation. But it sure isn’t an electrified noodle dancing in a jar. We’re basically talking about a sourdough starter, here.

No matter the true origin, it all comes down to this: Shelley and Byron, absolute doofuses of the century, thought that Darwin, in his studies of microorganisms, was instead examining a loose piece of wet pasta.

Now sure, the fault could have rested with Mary mishearing the conversation—but I doubt it. In her 1831 introduction to the third edition of Frankenstein, she actually discusses the whole noodle situation, even acknowledging that, “I speak not of what the Doctor really did, or said that he did, but, as more to my purpose, of what was then spoken of as having been done.”

Buy the Book

Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart: And Other Stories

Of course, it would be a great disservice to Mary Shelley to credit her masterpiece to this snafu, alone. Frankenstein was a story hard-won, containing wisdom gained only through immense pain. It held the grief of her mother’s death, her father’s rejection, the deaths of three of Mary’s children, the indifference of a narcissistic husband… A text so rich with longing and abandonment, so threaded with questions of nature versus nurture, life versus death, that it has become lauded as one of the greatest works in all of English literature—not to mention, the definitive foundation of the science fiction genre.

But also… without that fake noodle… where would we be?

Time is a paper chain—one link looped through the next. A gentle, seemingly insignificant action has the power to snowball into wars. A civilization’s rise and fall. The very birth or death of an idea:

The Etruscans invent pasta.

Pasta makes its way to Europe.

Dr. Erasmus Darwin writes of nature, of evolution, of microscopic beings, boiling over with effervescent life.

Two king-level morons discuss Darwin’s work—with one key mistake.

A teenage girl overhears. Begins a story. Invents a genre.

And from that comes Star Trek, Doctor Who, The Left Hand of Darkness, Alien, Aliens, Back to the Future, and yes, even Bradbury’s story “A Sound of Thunder,” itself. Thousands of links on the chain, blossoming into new worlds, space travel, AI—all the strange, marvelous, phantasmic universes science fiction has given us.

All traced back to one single, wriggling, imaginary piece of vermicelli.

Sources

Darwin, Erasmus. “The Temple of Nature.” http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Darwin/an01.html

“Erasmus Darwin.” Romantic Natural History. June 7, 2011. https://blogs.dickinson.edu/romnat/2011/06/07/erasmus-darwin/

“Erasmus Darwin and the Frankenstein “Mistake.”” Romantic Natural History. June 10, 2011. https://blogs.dickinson.edu/romnat/2011/06/10/erasmus-darwin-and-the-frankenstein-mistake/

Hay, Daisy. Young Romantics: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest Generation. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010.

Vasbinder, Samuel H. “A Possible Source of the Term “Vermicelli” in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.” The Wordsworth Circle , SPRING, 1981, Vol. 12, No. 2 (SPRING, 1981), pp. 116- 117. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24041230

GennaRose Nethercott is the author of a novel, Thistlefoot, and a book-length poem, The Lumberjack’s Dove, which was selected by Louise Glück as a winner of the National Poetry Series. Her forthcoming story collection, Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart, will publish in February 2024. She tours nationally and internationally performing strange tales (sometimes with puppets in tow) and helps create the podcast Lore. She lives in the woodlands of Vermont, beside an old cemetery.

It’s worth considering that Mary wrote her account fifteen years after the fact, at a point when her son was about to enroll at Harrow School. Between the haziness of distant memories and a need to burnish her reputation for her son’s sake, her story has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Notably, Mary says the conversation that inspired her was about “the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated.” Compare that to Dr. Polidori’s diary entry for 15 June where he says, “[That evening] Shelley and I had a conversation about principles,—whether man was to be thought merely an instrument.” Quite likely this was the “vermicelli” discussion. Given that Polidori was writing contemporaneously and couldn’t have known how important such a conversation would be, his account should take precedence over Mary’s.

Perhaps in the intervening years Mary misremembered who the participants had been (elsewhere in the introduction she confuses Polidori’s later novel Ernestus Berchtold for his submission to the contest), or she decided it was better to associate the idea with Byron than the doctor, for whom she shows a clear disdain. If it was indeed Dr. Polidori, an Italian, who was expounding on Darwin, it becomes more likely that Mary misheard “vorticella” as “vermicelli.”

Loathe to leap into the old “who created science fiction” debate, since it always pivots on a dreary question of semantics: “How do you define science fiction?” But I will note that Voltaire, Cyrano de Bergerac, Johannes Kepler, and Lucian of Samosata, among others, have some claim to writing science fiction before Mary Shelly was born. Whatever the case, it takes nothing from the brilliance or originality of her iconic creation. And I’ve always loved the story of how Frankenstein came to be written.

@1 – John William Polidori was British, born and bred; it was his father Gaetano Polidori who was an Italian emigre, who married an English governess, Anna Maria Pierce, after settling in England.

His sister Frances married another Italian emigre, Gabriele Rosetti; they were parents of the renowned Rosetti siblings. Polidori died young (25), and thus never knew his talented nieces and nephews.

(Dying young seems to have been the hallmark of the men of that generation of English Romantics such as Keats and Shelley; Byron died at the comparatively advanced age of 36.)

@3 – Polidori was ethnically Italian and spoke the language as attested to by his diary. After leaving Switzerland, he spent several months futzing about in Italy, which gave him the inspiration for his novel Ernestus Berchtold. Combined with the fact that he was a medical doctor, it is unlikely he would have confused vermicelli with vorticella.

@@.-@ he might not have, but it is entirely possible that Mary, potentially slightly intoxicated by whatever they were using at the time, misheard him.

PedanticallY –

“The Etruscans invent pasta.

Pasta makes its way to Europe.”

Etruria is in what we know as northern Italy, which I believe is in Europe…

This article is an absolute delight

The way literary history should be written! Thank you for my wake up read.

About the wormy, and the spontaneous generation of life—here’s to Louis Pasture and his swan-necked flask.

Boil some vermicelli—or whatever—in the flask. Leave the neck open. In a week you have ‘spontaneous’ generation of life.

Put some vermicelli broth in the flask. Leave some broth in the bottleneck, so no air can get through. Boil the liquid in the neck and the flask. In a week the broth in the flask remains sterile.

There is no counting the billions of lives that have been saved by Pasture’s swan-necked flask.