“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.”

How many of us can recite this line from memory? I admit, I get tripped up in the details, but the first sentence is gold, and the image it conjures up is even better. For me, it’s one part Peter Jackson, one part Rankin/Bass, one part the way I imagined a hobbit-hole before I’d seen any movies. Tidy. Cozy. Warm. Wood-lined. Part of a tree, part of the earth, close to all the things I cared so fiercely about when I was a small kid hearing The Hobbit read aloud for the first time.

I have been reading a book about a house—of course, a book about a house is never just a book about a house—and it has left me feeling a little scraped and raw. It’s the kind of book that starts out feeling like a rollicking adventure and then burns away layers until you remember that every house has seen (or will see) things good and bad, seen life and death and the little moments and the large. Fictional houses can seem like havens because we only get to spend a little bit of time with them. But that time, however brief, can be hugely influential.

For me, it didn’t start with hobbit-holes. It started with The Wind in the Willows—specifically, the edition illustrated by Michael Hague, in which everything is rich and saturated and looks as welcoming and comfortable as a well-worn velvet sofa. I haven’t even seen a copy of this book in years and I can still see Mole and Badger and Rat and the rest; I am still shocked that I have not yet cross-stitched the words “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats” and hung them on the wall. (Do I regularly mess about in boats? No. Did I when I was small? Yes, whenever given the opportunity.)

The warrens and homes of The Wind in the Willows were cluttered, but perfectly so. Things had places they were meant to go. Wood furniture, things hanging from the rafters, large tables and roaring fireplaces—put them all in my house.

(Some may have loved Toad Hall more, but to a kid, it was the place you’d be nervous about breaking something. No, it’s a den for me.)

And a den is very like a hobbit-hole, in some ways. Cozy, warm, practical, built for meals and guests. When I got a little older, though, I discovered the other place in Middle-earth that I desperately wanted to live: Lothlórien. Living in the trees! I had never even heard of Swiss Family Robinson, yet was obsessed with treehouses, with the idea of being up, up, up among the secret branches, the ones that in normal trees were too flimsy to hold much weight. Magic trees were clearly different.

But the logistics didn’t really matter. It was just the idea of this golden magical wood that somehow, wise and clever like the elves, had everything a person could need. I imagined it sort of like the forest in my childhood copy of The Twelve Dancing Princesses, all golden and beautifully impractical. I never got around to imagining the elves’ actual homes. Just the trees. Trees that were home—no matter how distant Middle-earth seemed, that I understood.

In elementary and middle school, I encountered a lot of houses that were both basic and beyond my understanding. My idea of New York City was a mash-up of contrasts: the apartments of All-of-a-Kind Family (five sisters in one room!); the expansive, incredible museum in From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler; the magical New York in So You Want to Be a Wizard. I loved The Westing Game and had absolutely no idea how to imagine an “apartment house.” I knew it was on a lake, but I had no idea how big a lake could be. I imagined a sort of tower that was also a house, a hotel that had house-like characteristics. I can still almost see how wrong I was.

And then there was the concept of the beach house. Some of you may have met this concept in a normal sort of way: by being in one. I discovered it in William Sleator’s Interstellar Pig, in which a kid on vacation at the beach meets some very interesting neighbors who are playing an even more intriguing board game.

Beach houses—the real things—never lived up to my youthful imaginings.

Fantasy is full of homes that a reader may or may not imagine as the author saw them. The house in The Forgotten Beasts of Eld, which I envisioned full of libraries and animals, a mountain house that was isolated but comforting, cozy and stern at once. The weyrs of Anne McCaffreys’ dragonriders—how did we picture those? What did they look like? Why does my brain hold onto a single image of a hallway from a Melanie Rawn book when I can’t remember which book, or why that location might be important?

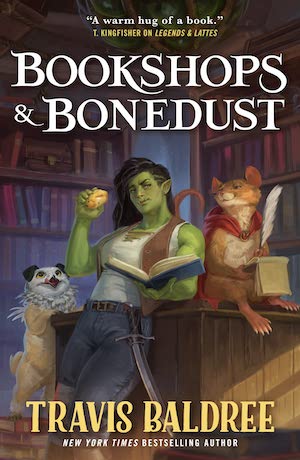

Buy the Book

Bookshops and Bonedust

Somewhere in all of our heads is a feat of utterly impossible architecture, all of these places connected, like an M.C. Escher drawing of towers and forests and clean stone walls.

Where I wanted to live as a teen, though, was slightly simpler: a house that was a cross between the Addams Family house and something you’d find in an Edward Gorey drawing. There is no other explanation for how old Victorians and their ilk danced into my head and settled there. They are not hobbit-holes (though you could make one just as cozy). They are not tree-forts or railroad apartments. But they are still my brain’s highest idea of a perfect house—at least of the kind a person can have.

(Of the magic kind, there is nothing better than Howl’s castle.)

There’s probably a lineup of houses in your head, too. They aren’t always easy to access; I had to think more than I expected about where I had found all my ideas about home and comfort and an ideal use of space. (And this is only what lodged in my psyche early; there’s a whole other list of houses and castles and dens from my more recent years of reading.)

Like so many other things in books, these concepts seep in when you aren’t looking for them. A book is a story about how even the smallest of us can have important roles to play, but it’s also a story about what matters to different people and where they feel safe. How to live comfortably, and how that can mean so many different things. (Let us not forget the raft people of Earthsea!) Some want to be close to the earth. Some want to peer into the distance from the tops of trees. And some make mountain homes far up in the cold north that are still the warmest places of all. What we read shapes how we see the world, what leaps out and what fades back—and colors how we want to live in it.

What does your magical architecture look like?

Originally published September 2022

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.

When you say magical architecture, I’m reminded of the conundrum between architectural thaumaturgy or thaumaturgical architecture from Sarah Monette/Katherine Addison’s Doctrine of the Labyrinth. Since that series also coins (to me at least) the term mikkary, it’s not cosy.

For me, cozy magical architecture would be to fulfil the promise of a Smart Home without the drawbacks imposed by capitalism and tech bros. The magic house should be a friend, to care and be cared for in turn.

When I was a boy, I became completely enamored with Captain Nemo’s wonderful Nautilus in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. How could I not want a secret, comfortable home that goes places? My love for Middle Earth, Federation starships, and all those other venues followed, but that submarine remains my inner touchstone; messing about in boats, indeed!

The House in Piranesi is, if not precisely cozy, a wonderful and beautiful space. Fantastical architecture for sure.

Ok, it’s not fantasy, but I want to move into Vorkosigan House…

When I think of comforting architecture, I think of Arts & Crafts, or Art Deco… and when you walk in, there is a baize door that leads to The Library. All the books I read as a child/teen featured cozy little homes, that had infinitely huge libraries “attached” in some way (“It’s bigger on the inside!”) They had comfy chairs, perfect lighting, and cozy places to curl up and sleep. Their shelves were well-ordered (somehow knowing which criteria was the most relevant to me for *this* particular adventure!) I will still pick up any book that has the word “Library” in the title, hoping to revisit, through their pages the space of comfort and safety I went to as a child.

Edgewood from Little, Big has long been my aspirational house

When it comes to Middle-earth architecture, lots of people are drawn to Bag End, which is entirely understandable, since it’s got such a lovely depiction in that first chapter of The Hobbit. However, when I think of Middle-earth architecture, I think of Minas Tirith. (the city from the Third Age as opposed to the fortress from the First Age). It’s vivid description and half-vacant status in The Lord of the Rings made it sound both haunting and haunted.

In Dan Simmons’ Hyperion, there were houses with room on different worlds, connected by portals…

Speaking of The Wind in the Willows, I always loved Inga Moore’s 1996 illustration of Badger’s kitchen.

Fans of cozy fantasy should check out Wyngraf, a print magazine focused on this subgenre. They have four issues out, and some really terrific stories.

(I do not edit or produce the magazine and get no kickbacks for this!)

The Hobbit and LotR are filled with cozy, delightful homes and settings for homes, Lothlorien and Bag End being only two.

Rivendell is famously the Last (or First) Homely House. I don’t recall that we are given much specific description, but are left with the impression that it’s a comforting place to stay whether you are an Elf, Man, or Hobbit. (Bilbo, for example, lived there happily for some years.) Elrond seems to have put a lot of effort into an environment that balances the grandeur and architecture of the Elven cities of his youth such as Gondolin and a coziness where any of his guests can feel comfortable.

Beorn’s Hall seems to me to be a weirdly comfortable and livable mix of a Norse hall (without the mead and meat), forest Amerindian longhouse, and very well kept stable. Once you get used to his animal friends taking care of you, I suppose it could be delightful.

There is a dark aspect to Bag End which I’ve never seen addressed. The chain of ownership and residency that we know of is Bilbo’s parents, Bilbo, Frodo, the Sackville-Bagginses (Lobelia and Lotho), Sharkey/Saruman, Frodo again, and finally Sam and his descendants the Gardners.

It’s in the middle there that there’s something dark. Lotho S-B lived there when he made himself Chief Shirriff, and then Sharkey. Wormtongue would have killed (and possibly cannibalized) Lotho in that time, presumably in that house. One wonders if Hobbits have some sort of ritual such as smudging or exorcism to purify or remove the bad influences from a place; on the other hand, I think it unlikely Tolkien would have written about such a thing.

@11: When I first read The Lord of the Rings many years ago, I was fascinated by Lothlorien, but now I think that I would prefer to visit Rivendell instead, in large part due to the implied knowledge and lore to be gained there.

I know that I have read fantasy works featuring cozy spaces, but they are not coming to mind right at the moment. One example that did come to mind is from Dragonworld by Byron Preiss, Michael Reaves, and Joseph Zucker. The protagonist, Amsel, is a hermit and inventor who lives in a house in the forest that is built into the base of a giant tree. He unfortunately loses his home fairly early in the story, but until then, it seemed like a very nice place to live.

@10: Thank you for sharing this! I had not heard about Wyngraf until now, but it definitely looks worth checking out!

@11 re: smudging; I like to think that the dust from Galadriel’s box did that for the entire Shire, Bag End included.

I love the idea of the Elven bower mentioned early on in LOTR–the one that’s actually in the Shire. Sometimes the local spruce trees, while they are still saplings, will grow so tightly spaced that their branches form a semi-permeable roof yet far enough apart that you can get between them if you don’t mind not standing up straight. I have enjoyed two such bowers, which keep off so much of the rain, snow, and wind that you could sleep underneath them wrapped in a woolen cloak with a hot stone at your feet. Of course this type of growth is temporary, but I imagine Elves keeping the trees small through sheer force of will. There are also cottonwoods that grow into fantastical shapes here, some resembling natural bridges, others benches or couches. They aren’t actually safe to sit on–for a mortal.

I know it’s not a home, but I wanted to just take up residence in the Inn of the Last Home in Solace from Dragonlance.

The dining room onboard Serenity in Firefly… a little space of warmth and laughter in the midst of the void.

Rivendell was also my first thought. Cozy, but also open to nature.

This is probably what nobody was asking for, but the last book I read that had some interesting architecture was Horrostor and….that’s not exactly a cozy space, haha.

But thinking of childhood – Green Gables, I think. I still have visiting Prince Edward Island on my bucket list.

My very first online fandom was Beauty and the Beast, the fantasy romance TV series starring Linda Hamilton and Ron Howard. The series is set partly in the Tunnels, a physically impossible network of disused infrastructure, smuggler’s diggings, and dry caves beneath Manhattan. The other impossible part, besides the lack of waterlogging, is that the Tunnels are so perfectly concealed that there are no records of them and their entrances can’t be seen from the street.

The Tunnels shelter a community of people who are, for one reason or another, socially dead: unemployable, freakish, cast off. They can’t be made use of by the powers that be, so they are grit in the social gears; better that they disappear themselves before they are, one way or another, made to disappear. They have become scavengers and handicrafters, some living in the Tunnels for life, some reinventing themselves and going back Above to keep the secret and pass on supplies that the Tunnel Folk can’t find for themselves. They also keep an eye out for people who might need a safe place.

The Tunnels are, above all, a safe place. People live quiet, comfortable lives, warmly if oddly dressed, with company when they want it and privacy when they don’t. There are playrooms, libraries, private rooms, a common kitchen, even a ballroom. Kids run around, people read contentedly, they make useful and beautiful things, and nobody with the power to do them harm knows they exist.

@18: Thank you for mentioning Beauty and the Beast! I was in high school when the TV show first came out in the late ‘80s, and the atmosphere of the show and the Tunnels made a significant impression on me.

The idea of an underground haven for misfits is a trope that comes up repeatedly, although unfortunately the plot of such storoes often involves that haven’s disruption and/or destruction. One example that comes to mind is Above by Leah Bobet, about a group of misfits living under Toronto; their lair is neither as large nor as comforting as the Tunnels in Beauty and the Beast, but there are some similarities.

A cozy place is in Grass by Sheri Tepper, that contains a city in the trees, made by the now extinct race that lived there before humans came.