It is a truth universally acknowledged that a Fallen Woman of good family must, soon or late, descend to whoredom.

Sarah Tolerance is a Fallen Woman of good family—instead of making a proper marriage she ran away years ago with her brother’s fencing instructor. She doesn’t want to be a whore, so she makes a living as a private investigator in a Regency London that’s just a little different from the Regency London you think you know.

The very idea is delightful—noir detective crossed with Georgette Heyer.

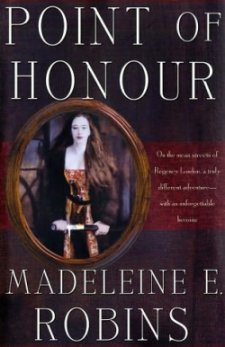

Point of Honor (2003) and Petty Treason (2004) follow the adventures of Sarah Tolerance as she solves her cases in the Queen Regent’s England. They’re charming, with just the right degree of mystery, adventure, period detail and romance. The mysteries are mysterious enough to keep the plot going as Sarah moves between the underworld and the upper classes. They’re more reminiscent of Kate Ross than anything else I can think of.

Madeleine Robins makes surprisingly few flubs for an American setting a story in England, and most of them can be attributed to the changes in history—though I do have trouble swallowing the idea that a change in regent would have altered the way parliamentary democracy works. (You have to accept that a change in monarch would mean a change of government. What?) As with Anathem, I was considering what these books gained by not being in our world, and unlike Anathem I think I’d like them better if they were further away, if they were set in a different world and were outright fantasy rather than just a fantasy of female agency.

They’re great fun though.

Something like Kate Ross? Let me at ’em! Woohoo!

As soon as I saw that in this historical line women had their own coffee houses–and without suffering the fate of Olympe de Gouges and Madame Roland–I was enchanted.

if they were set in a different world and were outright fantasy rather than just a fantasy of female agency

I don’t know, maybe it’s the sleep deprivation speaking, but it seems to me that the punch of the female agency-fantasy would be diminished if the world weren’t so very, very close to our own and had all the known Regency social expectations to be working against.

(Also, yay, commenting in Opera working! Don’t know when this happened but I appreciate it.)

Though I haven’t read the book, I can handwave around that if I have to.

The government is based on an cabinet that has been selected by a PM who is invited by the Monarch to form the government. If the current Monarch did not invite the current PM to form a government, then their ministries don’t have the legitimacy as officers of the Queen and will be unable to fulfill their duties until blessed by the new Monarch.

:)

Yes, that’s a perfectly good handwave, but it isn’t the way it has ever worked, ever, and there’s no explanation for how and why and when it changed.

It’s as if I wrote a book saying that in the US every time there’s a new President of course they’ll just naturally because it’s the way things work have a majority in Congress. I can imagine it being perfectly sensible (handwave) that it be so, but it isn’t the case and never has been that a US President has a majority. Similarly, new monarchs do not automatically get to recall prime ministers and have new governments. It could work that way, but it doesn’t.

It’s a niggly minor flaw, that’s all.

Bless you, Jo. I’m glad you liked it. It’s always perilous working in someone else’s when and where; I’m only glad I pulled it off with as few flubs as I did.

As for the politics–I was working from data indicating that at the point when it became obvious that the Prince of Wales was going to be made Regent, he was suddenly everyone’s new best friend; the hope (on both sides) that his elevation to some sort of authority (a far more toothless authority than he hoped for, but hey) would mean the elevation of this person, that party, etc. Many of the Whig party felt that the Prince betrayed promises–or hints at promises–he’d made them over the years.

I love the Prince of Wales. He’s endlessly fascinating and sad.

Can I just support Madeleine Robins on the political issue here? In the 18th Century, the King did have a hand in choosing the government. Not a completely free hand – he had to choose people who could command a majority in Parliament – but with the party system less rigid than it is now, that still left him with some leeway. When George III became King in 1760, he did change the government. When The Prince of Wales finally became permanent Prince Regent in – what? – 1812, he was widely expected to change the government, and, when he decided not to, expressed his decision by saying ‘I will keep my father’s ministers.’ I think that even later than that there were occasions when the King had some input into who would be Prime Minister, though his powers became less sweeping as time went by.