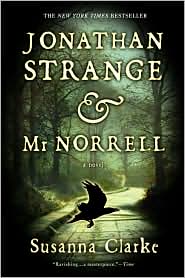

Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell was published in 2004. When I first read it in February 2005 I wrote a review on my Livejournal (full review here), which I shall quote from because it is still my substantive reaction:

It’s set at the beginning of the nineteenth century, in an England that is the same but distorted by the operation of magic on history, and it concerns the bringing back of practical English magic.

What it’s about is the tension between the numinous and the known. The helical plot, which ascends slowly upwards, constantly circles a space in which the numinous and the known balance and shift and elements move between them. It’s a truly astonishing feat and I’ve never seen anything like it.

I’ve just read it again, and I could pretty much write that post again. In summary—this is terrific, it reads like something written in an alternate history in which Lud in the Mist was the significant book of twentieth century fantasy, and it goes directly at the the movement between magical and the mundane.

I wasn’t the only person to think this book was brilliant. It won the World Fantasy Award, it won the Hugo and the Mythopoeic, it was Time Magazine’s number one book of the year, a New York Times notable book, it was in the top ten of almost every publication in Britain and the U.S. and it was a huge international mega-bestseller. It did about as well as any book can do.

But five years later, it doesn’t seem to have had any impact. Sandcastle fantasy is being published all around as if Clarke had never put finger to keyboard. I wonder why that is?

It may be that it’s just too soon. Publishing is astonishingly slow. Books being published now were written several years ago. Influence does take time to permeate through. But wouldn’t you think that in five years you’d start to see some influence? But even without publishing speed, it could take longer than that for Clarke’s influence to be assimilated and reacted to. I shouldn’t be so impatient. Ten years might be a better measure.

Or maybe it will take a generation, maybe the people who read Clarke when they were teenagers will grow up to write fantasy influenced by her, but it’s not going to happen with people already grown up and publishing and set in their ways?

Perhaps it’s just sui generis, so wonderful and unique that it can’t really be an influence except as a spur to excellence?

Or maybe, in the same way it doesn’t appear to have a much in the way of immediate ancestors, it can’t produce descendants? It’s wonderful, but it’s not what fantasy is, it isn’t in dialogue with fantasy and it’s hard for fantasy to engage with it?

After all, what do I mean by influence? There’s plenty of fantasy set in Regency England—there’s Novik’s Temeraire for a start. I don’t think we should have a sudden rash of books about Napoleonic magic or books with charming footnotes containing short stories. I don’t even want more books directly using faerie magic. (We have had some of those too.)

What I would have thought I’d have seen by now is stories that acknowledge the shadow Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell cast across the possibilities, things that attempt to engage with the numinous in the way it does. Fantasy is all about ways of approaching the numinous—and everything I read is still using the traditional approaches. That’s what I keep hoping for and not seeing.

Perhaps it will happen, given time.

Meanwhile, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is there, it’s incredible, and one can always read it again.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I have bounced off this book twice. Must try again.

In terms of feel, and as you put it, engaging the numinous, the only thing I could compare it to in my mind is Le Guin’s Earthsea series. I’ve always thought that Le Guin was the only author (until Clarke) I’ve read that truly captured the mystery of magic. The wizards of Earthsea have their university, they study magic, but especially in her later books, it’s shown that they don’t really understand it at all. The same is true for Norell and Strange.

I absolutely loved this book when I read it, but it took me a little while to get through it.

I think one of the big strikes against her is that it’s a large, complicated book – at least for getting the public behind it – but also because the Clarke hasn’t really followed it up with anything to keep her name in people’s minds.

A great book that I enjoyed tremendously . . . but once I was finished, I didn’t greatly attached to.

Its world doesn’t afford vicarious membership.

Does that make sense?

I think Dholton at #2 nails why this book isn’t more influential; it’s the same reason it stands out. 95% of contemporary fantasy is written in a very naturalistic mode, with the “fantastical” elements explained in great sociological detail. It’s ironic that this post came up in the middle of Urban Fantasy month, since UF is the foremost genre of highly resolved fantasy. This is the literature that answers questions about what vampires and pookas do with their off time, rather than just allowing them to subside back into unknowable numiousness. What people are reading in increasing amounts is knowable fantasy, so to speak.

So Strange & Norrell actually doesn’t fulfill some of the narrative expectations, and hit some of the narrative pleasures, for which contemporary readers come to fantasy novels. I like it for that reason, but I’m not sure enough people do for it to hit a critical mass of influence. I think it’s destined to remain an outlier.

Also, to be fair, the story drags in the middle.

Happy to see the connection drawn between Strange & Norrell and Lud-in-the-Mist (actually, happy to see any mention of Lud-in-the-Mist ever) but I don’t have any particular theories as to why it hasn’t been more influential yet. If I were to guess I would guess it’s simply going to take longer for the book to sink in, because it is so different from the way magic is usually treated and currently exists in a sort of vacuum.

And maybe it is just that that view of magic doesn’t jibe with the emphasis on rules and rationality that the fantasy genre (and its readership) currently embraces. . . might also explain why Patricia McKillip (whose magic is numinous and lovely and dangerous and unknowable) is not as popular as it should be. . . people want magic to be explainable, so even though they might enjoy a single novel where magic isn’t as a novelty, they don’t embrace the viewpoint at its core. . .

This book was a best-seller because it was fashionable to say you were reading it, but how many people have it on their bookshelves still unread? Many, many, many.

As Andrew @@@@@ 3 pointed out, it’s large. As seth @@@@@ 5 pointed out, it drags in the middle. (In fact, I would suggest that it drags the middle third.) As OtterB @@@@@ 1 pointed out, it’s easy to “bounce off” if you don’t really persevere for the first fifty pages or so. Also, it has copious footnotes, and its genre is somewhat hard to quantify. Simply put, this book is hard work. Mostly fun and ultimately worthwhile work, but work nonetheless. And thus it remains unappreciated by the wider world.

Should it have had a greater influence? Certainly. Will it? Unlikely. At least, not until it’s made into a movie, the watching of which will involve less work. ‘Tis the way of things, I’m afraid.

“…maybe the people who read Clarke when they were teenagers will grow up to write fantasy influenced by her…”

If not before that, yes, then. At least, I read Strange and Norrell as a teenager, and I’m certain that my love for it influences my work (along with my feelings about Harry Potter and urban fantasy and everything else).

Like Stefan @5, I enjoyed this book and when I finished it I really wanted more, and yet I don’t feel a strong attachment to it.

I think part of it is the Regency style of the prose (which Clarke did VERY well). I’m not a fan of overly dense prose, and this, while not at Dickensian levels, is rather dense. The footnotes, OTOH, are not a problem for me. I’ve loved stories with footnotes since the first time I read Jack Vance.

I was also somewhat frustrated by it, because it seemed that the focus was always away from the really interesting bits. And as I said, when the book ended, I felt like it was just really starting and I wanted the story to follow Strange and Norrell.

A wonderful book that I enjoyed greatly, yet have no desire to read again, even though I know I would like it and would get even more out of it a second time around. Paradoxical, which is a very fitting thing for this book.

For those that’s interested, we ran a seminar with Clarke on the novel a few years back – to be found at http://crookedtimber.org/category/susanna-clarke-seminar/. But I wonder whether the ‘is it influential’ question quite the same as the ‘does it have obvious heirs’ one. I think that there’s a fair case to be made for John Crowley’s _Little, Big_ being one of the most influential fantasy novels of the last thirty years – but it has remarkably few obvious heirs (two stories by Elizabeth Hand and Gene Wolfe are the only obvious exceptions I can think of, along with perhaps a couple of Richard Grant’s novels).

Strange & Norrell is a gorgeously-written story, but unfortunately, the things I love most about it (antiquated sentence structure, grand storytelling, unrushed pace) are precisely the opposite of what seems to appeal to the Harry Potter generation. They expect bright, flashy books that do all the thinking for you. Strange & Norrell is dark, dense and complicated, and cannot be fully appreciated unless the reader engages with the tale. The sheer length of the book would be enough to turn off a lot of people, as well. I don’t believe it’s possible to make a book like this accessible to those who expect instant entertainment without completely changing its character.

I highly recommend The Ladies of Grace Adieu, also by Susanna Clarke, to those of you who have not yet read it.

It’s sui generis. But, wow, what a beautiful work of art. I somehow fell into re-reading a favorite snippet (the scene leading up to the aside that men would smile and say Mrs. Brandy — being a woman — knew nothing of business, but that women would say she knew her business very well indeed: to make Mr. Black love her as much as she loved him), and somehow fell into re-reading the whole thing.

It’s such a rewarding, marvellous work, but I think the things that make it so rewarding may be very much bound up in the mode of storytelling. My very favorite scenes are those which just play that 19th century mode of writing and characterization to the hilt, but you know that beneath that is a modern writer’s sensibility (so, for example, the moment Strange turns his back and is silent on receiving unexpected news, and Mr. Norell completely misses what’s going on).

The other memorable parts, related to the magic — especially, I think, towards the end when everything falls together (hint: ravens) — is in itself not new, I think. Really _magical_ magic — not the rules-bound magic of so many modern fantasies (Jordan, Sanderson, Erikson, etc.)– is still being written about, and quite well. But there’s something about how it meshes with the sometimes deliberately-straightlaced nature of the narrative that just heightens the miraculous nature of it.

I loved this book–and I think it has at least one obvious inheritor in Lev Grossman’s The Magicians. There’s one scene of magic-making that felt lifted right off the pages of Strange & Norrell, and Grossman’s cited it as an influence.

Seth has a good point. This is a book for people who don’t usually read fantasy, as I can attest, since I rarely do myself (Steven Brust aside). It’s effective because it’s grounded in a real time and place, itself quite rich and a bit strange to us, and made stranger by the introduction of a single fantasy element (which, in fact, makes it a lot like well-constructed science fiction). The way it borrows its style from Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, possibly among others, reinforces that. It’s also feels realistic in what we’re left to imagine for ourselves; only a writer has access to all the low-level detail that often goes into a fantasy novel. You can’t have strangeness without a norm to depart from, and if that norm is itself both real and familiar but out of sync with our own experience, you have something particularly telling.

Why wasn’t it more influential? Possibly because it’s unusually demanding of both writer and reader. Perhaps you could cite books like Sense and Sensibility with Zombies. More seriously, it’s the same sort of ballpark Neil Gaiman often plays in, making use of detailed knowledge of historical texture and folklore to give texture and substance to a fantasy. Gaiman was one of Clarke’s models, and he was in fact the one who got the novel published.

I tried to like it. I wanted to like it. But I bounced off it too. There were times when I thought it was brilliant, but there were other times when she went off into another aside about something or other and I just thought, “oh, for goodness sake, get ON with it!” In the end, I gave up on it about a third of the way through; the plot-to-words ratio was too low for me.

I notice our new remainder shop has plenty of copies of it in their 5 books for £1 section…

I loved it.

But I think a lot of commenters have hit the nail on the head when they emphasize that this is a hint, rather than show, rather than tell method of writing fantasy. It isn’t easy, it isn’t always clear and, ultimately, that means that it requires effort.

When I finished it, I was left wanting more. It took me a fair amount of time to decide that I was happier with less.

This is a book in the vein of Crowley, Gaiman and Wolfe and while those three have all been successful, Rowling and Harris sell more novels.

This is one of my favorite books. I didn’t find it difficult to get into, or tedious in the middle–I got sucked into the world and put it down 2 weeks later, blinking.

Maybe it’s not easy to see how it’s been influential because there are so many different ways it could be influential? There’s the nature of the magic, and the intricate worldbuilding, and the modern sensibility masked in Edwardian forms. There’s the masterful incluing in the footnotes, explaining what you as a reader in the world are already supposed to know.

For me, the really amazing, influential thing isn’t unapproachable numinousness. It’s the way the characters keep trying to understand the numinous. This book gets academic research in a way I’ve never seen elsewhere. The universe is huge and vast, and not only impossible for one person to understand, but probably impossible to understand perfectly with the resources of a species. But we try anyway. We run our studies, and scrape together fragments of knowledge, and learn and build and think of ourselves as experts–and every once in a while something happens and we’re reminded that the universe is huge and vast and beyond perfect understanding.

Strange & Norrell is truly incomparable, and I wholeheartedly agree with everything you said about it. I wonder if the recent scad of classics-and-horror novels isn’t influenced, at least in part, by Clarke’s work. And unless I am mistaken there was, very recently, a regency+magic book that was revied on this very website. But being influenced by Clarke… There’s something so singular and unique about that book that I don’t think anyone would dare to try writing something in the same vein.

That said, when I finished S&N I didn’t go look for more of the same. What I did was read the entire ouvre of Jane Austen.

I’m not sure I understand the question and its grounds: are you (Jo) saying that the most important aspect of this book is the way that it deals with magic (that is, the balancing of the unknowable numinous and the rigorously scientific); and asking why no one else has taken this approach since? (With the additional note that Clarke’s take on magic itself seems as ancestor-less as it seems descendant-less.)

I may agree that fantasy today tends towards explanation/knowability (it’s an old joke, but you can imagine Kafka being workshopped to death, with people asking for more clarity), and so Clarke lies as an outlier there (with Vance and Peake and a few others writing with the same approach towards the unknown and the knowable).

But I’m not sure that I’d want to say that Clarke’s influence should be primarily felt in that area because I think that her approach towards the fantastic is couched in her historical setting. That is, she not only creates for us a fantastic world and then unleashes it on our shared real world (like much of the urban fantasy that has been discussed here recently); she creates a fantastic world and then unleashes it on another world–the historical world.

Which is why I don’t think it quite fair to Clarke to boil her historical setting down to Regency / Austinmania, as in the case of Novik or Grahame-Smith. (Although clearly there’s something about Austin/Regency that attracts attention; I’d guess that, like the interest in mid-to-late 19th-century steampunk, contemporary readers can see some strong correlations between our time and that time in the past, while still maintaining enough distance to treat history as something of a sandbox.) I think her historical approach is as important as her approach towards the fantastic. Or, in other words, they’re the same approach.

I’m another who has bounced off it twice. I persisted over 100 pages in both times, but found I just didn’t care enough to continue. It’s not that I’m unwilling to put forth effort in a book, but I have to get something back, and in my two attempts, I just wasn’t getting enough back to be worth the effort. I loved the idea of it, and was eagerly looking forward to reading it, but just couldn’t get into it.

I admired the novel very much, and enjoyed it to a degree. But the setting, the characters, the voice — it’s cold. Appropriately cold for such faerie and magic, but nevertheless cold.

Also there’s a section of about 80 – 100 pp that really shouldn’t have been included, which dragged the pacing way down, from it’s already rather slo mo progress.

That said, it seems there had been influence, among those notable, Richard Galen’s The Magicians and Mrs. Quent — though it is much warmer and follows more closely the now traditional model, i.e. this wasn’t a standalone, after all, as we learned when finishing it.

Love, C.

@henry Farrell – I’m not sure how you can call a book influential if it doesn’t have any heirs, or am I misunderstanding your use of ‘influential’?

I’ve never been able to get through this book and it is odd because everything about it seems like something I would enjoy, heck I breezed through Stephenson’s Baroque cycle without any trouble at all and I was terribly excited about this book, especially after hearing all the good hype. Nope. Just bored me to tears. I haven’t tried again recently but I keep resisting doing so since there are so many books on my ‘to read’ list that I’ll more than likely enjoy.

Well, where’s your book influenced by it?

Foxessa may have put her finger on the reason why I bounce off this when she calls it “cold.” It’s been several years since I tried it, but I remember a sense of distance and as a result it never fully engaged me. There was never a throw-it-across-the-room moment (a good thing, considering its heft), but I set it down and never felt compelled to go back to it. Maybe I should pack it as my only reading material for a long flight…

Strange & Norell left me cold, too. Not sure why, maybe the ending comes unstuck from the beginning and it falls apart. I can read difficult works — I think Lanark and The Night Land qualify.

I found The Light Ages far more involving.

Amusingly, Strange & Norell is on Ian MacLeod’s “What I’m Reading” page.

The only reason I finished this book was because I have an odd superstition that not finishing books is unlucky.

I hope it never influences any future fantasy authors as it was boring, unoriginal, lacked any likable characters, didn’t have much of a plot (or really a magic system for that matter) and was more in the flavor of 19th century gothic romance (see Mysteries of Udolfo) than a fantasy novel.

For me, the main appeal of this book was the voice. That’s not something other authors can replicate all that well.

I often wondered if the Victorian/Monster mash-up books were the tiny tornadoes flung outward from the hurricane of Clarke’s magnificent novel, wherein the archaic language style and modern, magical sensibilities merge into what feels like a book out of time.

I also wonder if this book isn’t so far away from the few notable books of out-and-out Victoriana I’ve seen, of late – THE SOMNAMBULIST, and DROOD, for instance.

To me, what is truly astonishing about the book is probably not going to be the thing that is easily reproduced by other authors: Clarke’s exceptionally skillful artistry. What is ready for the production line is the combination of modern fantastical concepts with a Victorian setting without the intrusion of Steampunk.

Even if that influence is still filtering up through the writers of our time, and the slow production process of novels, much of what made Susannah Clarke’s novel fabulous could not be reproduced in the same way that “vampires!” or “werewolves!” or “cities with demons!” can be milked over and over again. What influence results will not be so overt as to be easily measured.

Put me on the side of people who thought it was delightful — as I said at the time, “I wished it would never end…and at almost 1000 pages it very nearly doesn’t!”

I don’t see why you expect that great fantasy books should be influential. For example, Roger Zelazny’s Amber series was very popular (and for the first five books at least, deservedly so), and is quite different from most fantasy. In the thirty years since its publication, I’ve only seen a handful of works influenced by it.

On the other hand, the deluge of Tolkien imitations has still not stopped. I don’t expect that a generic Zelazny imitation would be better than a generic Tolkien imitation, but at least there would be more variety.

Hrm. I loved Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell to bits, but at the same time I never once thought about imitating it or trying to do something in the same vein. Lots of reasons why, some of which have already been touched on by other commenters.

1) Harry Connolly’s right that the voice (as expressed in both the footnotes and the main body of the text itself) is a large part of what makes the book work. And it’s a voice that’s difficult to match or imitate, even imperfectly – more difficult than that of Austen, I’d say. (In contrast, more modern authors like Chuck Palahniuk can be incredibly easy to imitate.) I think it’s a combination of word choice, and diction, and a certain archness of phrase.

(Also, I vaguely recall that the book was written in full omniscient rather than limited omniscient? Which is another way in which imitation might prove tricky.)

2) I don’t think that the book is cold or frigid, but I can see how others would say that. The narration is distanced. It’s not inviting you into the characters’ minds or begging you to sympathize with them. Which is pretty much the opposite of what most people understand as what you’re “supposed” to do.

3) It’s big, and it’s complicated, and it’s doing a ton of different things at the same time, and some of those threads are more accessible/imitable than others. The footnotes are very David Foster Wallace, and an incredibly difficult act to follow.

The Edwardian/Regency time period as a setting for genre stuff arguable has been imitated (if often badly) in the form of the various Jane Austen + Supernaturals mashups (all of which post-dated Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by several years). Actually, I’d say that if you want to talk about imitators or signs of influence, those books need to be on the list.

And the fae have their own sub-genre (sub-sub-genre, if you count it as a part of Supernatural Romance) discourse going on, including Stardust and Holly Black’s books and probably tons of other stuff that I don’t know about.

Really, I think what’s going on here is that Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is influential, and has been influential, but because it manifests as such a very particular thing, which is in discourse with many different threads of the fantasy genre, its influence is kind of riding off in all directions at once instead of carving out a single channel.

@12: …wait, _Erikson_ has rules-bound magic??

(Read it; liked it; not feeling an urge to reread it yet.)

–Dave

My sense, from recent writing workshops, is that its influence has been felt more strongly on the literary fiction side of the aisle, writing the fantastic is now an acceptable goal. This does usually involve a lack of appreciation of the difficulties of worldbuilding. I’ve not found a similar underestimation attached to the real world among genre writers.

Two questions for you? What would a descendant look like? And what is sandcastle fantasy?

BTW great post – Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is historical fiction so well created that it feels like urban fantasy. It is the one Kindle book on my iPhone. When the pleasure of reading is required, I can just click randomly and start reading. Bliss!

I thought “Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell” was an amazing book, but I’ve never recommended it to anyone. Why? Probably because it’s so difficult to catagorize, and, thus, hard to tell if the other person would like it. It is brilliant, but it was still a struggle to get through. All said, though, I’m glad I finished it.

And I think JMMcDermott (@28) is right about the swirling lines from “Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell” to monster mash-ups, “The Sommnabulist” and “Drood”. Clarke’s influence is actually very heavy, but lies in the background.

This book saved reading for me a few years ago. I was a burned out lit major who couldn’t return to the easy (and often poorly written) scifi/fantasy I used to consume in high school. It just wasn’t doing it for me anymore. Most of them were not interesting to me after four years of loving Kafka, Dostoevsky, Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, etc.

I piked up George MacDonald’s Lilith and got the renewed desire to read something else in genre again. My sister directed me to Jonathan Strange and I FINALLY had something hard enough to excite me. I loved it. I even gave myself a black eye by dropping it on my face while reading in bed. It’s a dangerous brick of a book. I just got it on my Kindle last week so I could do an easier reread.

Why does it not catch on with everyone? Well, it isn’t easy reading. There are footnotes after all and a lot old dudes. No cute little wizards in wizard school. It takes about 100 pages to get going and not everyone can deal with 100 pages of an old dude being crotchety while waiting for Strange to show up. People are trained to be looking for traditional magic gimmicks and not everyone can deal with something different like this. Half of it is like an English parlor mystery. I only recommend it to my lit major/college friends because I know they can get invested in it enough for the payoff. It is on my top ten books, but it is hard to recommend to everyone since I know lots of people don’t read at that level and wouldn’t get through it.

I thought this book was a masterful interplay of “real” life (albeit in the past) and the numinous as you say, Jo. I agree with PheonixFalls that McKillip uses magic in that kind of way as well, and Henry Farrel when he says that like “Little Big” this may be a one of a kind masterpiece, and while I disagree with wunder about this book I agree wholeheartedly about Ian MacLeod’s work. Le Guin and Wolfe must always be factored in to any discussion about genre literature! So Clarke, LeGuin, Crowley, McKillip, Wolfe and MacLeod – there you have my favorite fantasists of the last 50 years.

All the other excellent comments aside, I think Rachel @7 nailed the reason: It sold a lot of paper and won a lot of awards, but I’m skeptical that it was widely read. I loved it. But then, I’m in the midst of a reread of Trollope (Barchester *and* Palliser, thankyouverymuch).

I made it to the end of the second book of this (I bought it as a box set broken into three books). Although I found it readable, I simply ended up not caring enough about what happened next, and so have never picked up the third book, even though I own it.

My primary reasons for reading are wanting to know what happens next, or caring about the characters. Since I ended up with neither, I did not read on.

Peter1742: Not sure how you got the impression there are only a handful of works influenced by Zelanzy’s Amber. Heck, at this point there are more than a handful of novels out there which are “trademarks removed” versions of Amber Role-Playing Game campaigns! And that’s not counting long series from Brust and Stross with obvious influences…

Isn’t this a hard thing to do? I can think of a few other books that do it, but very few. I think a world in which this book had many heirs, quickly, would be a very different world.

I still have not been able to get through this book. I keep putting it aside for easier reads.

It may also be worth noting that if I`d looked for books influenced by LOTR five years after I wouldn`t have found anything.

@32,

It’s definitely rules-bound, originating as it did from his old RP sessions. But it’s true that the rules are both incredibly obscure _and_ incredibly permissive. :P

Brian2 @@@@@ 14

It was Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Unfortunately, the later Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters wasn’t nearly as successful a mashup. But I take your point in that they and their ilk may be descended from Strange and Norrell… hadn’t considered the connection before. On a related note, perhaps the Historical Urban Fantasy Soulless by Gail Carriger (who’s up for the Campbell this year) is also related to Clarke’s work?

kenneth @@@@@ 37

Thank you :) (And whew, all that Trollope! How… bracing.)

colomon @@@@@ 39

Indeed, Zelazny’s impact is felt far and wide! I see his influence everywhere; even in the Malazan Book of the Fallen series, currently undergoing a collossal re-read on this very site. (If you’re a Zelazny fan, please contact me here if you’d like to get involved in an article we’re putting together on the great man and his work).

Jo @@@@@ 42

Perhaps true, but it took LOTR, what, a decade to really catch fire with the wider reading public, whereas Strange and Norrell garnered an almost immediate awareness in the popular consciousness, enough so that even non-Fantasy readers (as seth and Brian2 mentioned) read — or at least, bought — it. Over time, Tolkien’s work sold more copies than in its original printing; the same cannot be said for Clarke’s.

Sure, The Fellowship of the Ring came out in 1955 but the trilogy didn’t get a paperback edition till at least a decade later, and there can be no doubt that the Tolkien Effect was being felt soon after that, when Terry Brooks started penning The Sword of Shannarra in ’67. And another near relative of LOTR, Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain books, started appearing in the early 60’s.

That Tolkien was more influential than Clarke will ever be is surely a given? A quick check of their respective Amazon rankings has the paperback of Strange and Norrell at #27,032 and a Tolkien box set comprising LOTR and The Hobbit at #3,797. Tolkien’s popularity increases, Clarke’s diminishes. Meanwhile, Breaking Dawn (the very antithesis of Clarke’s — and Tolkien’s — complex world building and elaborate prose) is at #17. Not saying it’s right; it just is.

To all the people who say it was widely bought but not widely read, or that it was fashionable to buy it — I really don`t believe that this happens. I can believe in faeries much more easily. And in any case, it won a Hugo, that great popularity award. I`m just not buying this at all.

Nolly: I don`t think I have written any fantasy since I read it that wasn`t influenced by it.

I can believe in faeries much more easily than I can believe that everyone who votes in the Hugo ballot has truly read everything for which they vote. I know several people, for example, who voted for The Yiddish Policeman’s Union in the year it won not because they read it and thought it better than all the other nominees but because they had heard it was better than all the other nominees. The Hugo isn’t always so much a popularity award as a name recognition award. And names didn’t get much more recognizable — and considered worthy of recognition, often sight unseen — than Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell in 2005.

Bluejo @@@@@ 45 Anecdote isn’t data of course, but I know a dozen or so people who bought or borrowed it and only three who finished. I tried twice and failed twice. It turned out to be a brilliant book that didn’t interest me at all.

Genre fantasy isn’t about the numinous. That’s why it grew out of SF as a publishing genre, I think.

Jonathan Strange &c was long, certainly, but not particularly hard to read. I liked the voice somewhat. But I never really bonded to any of the characters or situations; it was all very distanced and not that interesting. So — not hard, but not rewarding especially either. I read it because other people were so excited about it, and I didn’t find out why.

I found it much easier to read than the first Harry Potter book, actually — took me at least 4 tries to get started in the Potter, where this I just read through.

If you were going to a con dressed as Jonathan Strange, how would you go about it? If you were at a con and saw someone costumed as Mr. Norrell, would you be able to identify the costume?

Seth@5’s point about lacking vicarious membership has an emotional reason (always trust those emotional reasons, they’re usually the real motive) why the book hasn’t had more influence.

So let me ask you this: if a sequel were published, would you buy it? You did it once, but would you do it again, absent any other information, reviews, recommendations? Let’s say that you were offered an e-book, so no cover illo, no blurbs, no pocket-reviews, just buy it or not. Would you?

Why not?

The novel has an immense intellectual appeal but, I think, very little emotional appeal. It has enough to keep some interested, to finish the book, but once done, probably not enough to go on with. (I think it’s this that leads people to say that the story drags in the middle on the one hand, and that it’s very well-written on the other. Those two don’t usually go together.)

Having completed the story, I can’t say that I particularly care what happens to any of the characters afterwards. I am simply not engaged enough for their fates to matter. That’s really odd, because when that happens I usually can’t bring myself to finish the book in question.

I think Carandol said it for me, except in my case I ground to the end of all 800-odd pages because I kept thinking that sometime it must come together so I could finally get what all the fuss was about. But when I got to the end I thought–that must be about one of the most boring books I’ve ever read in any genre. Incredibly slow plot, incredibly unlikeable characters–Victorian language structure sure, but hey, we’ve moved on by at least a century, probably a century and a half from the literary style exhumed by this book. And although an earlier poster likened Clarke to le Guin I have to say that I (by and large) love Le Guin, find her writing clear,engaging and un-put-downable. I also think she’s a far, far better writer.

Someone lent me the book. I read parts of it, and didn’t hate it, but just thought I had better uses for so many hours of my life than reading it all. For the most part, it didn’t engage me.

I don’t think that the problem is that I’m insufficiently literary to appreciate it, because I have read and enjoyed lengthy 18th and 19th century books. I think that a weekend would be far better and more happily spent reading Boswell’s Life of Johnson or Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire than Ms. Clarke’s tome. Others may feel differently.

I listened to the book on audio instead of reading it in paper. That made a LOT of difference to me. I tend to get distracted by footnotes when I read, and lose the thread of the main narrative. The narrator I listened to somehow managed to make them fall seamlessly into the text.

And I thought the last third of the story was utterly engrossing, since everything had built up to that.

I adore books like this. To me, they’re much more satisfying to read than books like Harry Potter stories. The HP works seem like rather thin gruel compared to the full feast of JS&MN. And the whole fairy world, which is strange and full of capricious characters who are NOT just human beings with pointed ears or whatnot, is also ever so much more interesting than some of the modern urban fantasy tropes. At least to it is to me.

I suspect it takes a writer of a certain sensibility and skill to move comfortably in literary waters like these. Patrick O’Brian did it well. I seem to remember that Charles Palliser did it well in Quincunx (non-fantasy). Many of the current popular writers just couldn’t do it.

More anecdotal evidence of influence — and I’m not sure what any of it means — but my wife who doesn’t read SF or fantasy and really doesn’t know what’s going on in the genre gave me a copy of “Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell” shortly after it was published. That says something right there about the “buzz.” I know buzz is meaningless in terms of real literary influence, but it does produce a face for the genre to outsiders (and I’m not using that word to criticize or insult anyone).

Also, I frequent several used bookstores to find out of print books I missed. There is always a copy of “Strange and Norrell” on the shelves regardless of which store I’m in. I know that only proves many copies of the book have been sold (something we already know), but it also says it’s a book that many people see no need for keeping.

I said earlier that the book was a struggle to get through. I didn’t mean that it was hard to read or difficult to comprehend, I also called it brilliant. I wish I could write like that… I wish it had my name on the cover… But after a while, I found I only cared about two characters, Stephen and the man with the thistle-down hair. I confess to a preference for shorter books, but I still read the whole book (something I no longer feel obligated to do if I’m not enjoying a book).

Finally, after all these years I still remember a conversation I had with a friend who was in high school honors English. She was writing a paper on “The Hobbit” and was having difficulty finding relevant academic criticism on it. This was 1970 and I was one of the few people she knew who had even read the book. So things do take a while to simmer.

I read very little fantasy, though I did finally get around to S&N maybe two years ago, and yes, I recall that it does begin very slowly.

Most of my contact with fantasy is “Another magic sword/Otranto/witch/Tolkeinoid cover. Something being marketed to someone else entirely. (One of my own exceptions is that I buy everything of Tim Powers’ as soon as it’s in paperback, but again, sui generis.) Where in all this is the sf?” so I ask in honest ignorance: How much fantasy is there going on which might have existed if Tolkein, for instance, never had?

Boy, am I glad to have stumbled onto this thread, because I thought I was the only one who found the book really boring. Tried it twice, and each time gave up around page 150. Technically, it was OK, but there was nothing in it the least bit compelling; I’d read a chapter and think it was interesting enough, but never found myself drawn to read the next one, or at all curious about what happened to the characters. (That said, the early scene in the Cathedral was a great bit of writing.)

It has been argued that the Rolling Stones were more influential than the Beatles, not because they were better, but because what they did required less (although still considerable!) skill and talent, and so was easier to mimic. Same might apply here.

I wonder if I am the only person around who read this book, enjoyed it as far as she can remember, and still remembers nothing about it? I must give it another try.

cranscape @@@@@ 35: Have you read John Crowley’s Little, Big yet? If not, you should give it a try. It’s a totally absorbing fantasy novel that also satisfies those “literary” appetites you’ve been feeding with Kafka and Dostoevsky and Faulkner. It’s no surprise that it’s been mentioned in this thread already, because it’s good in many of the same ways that Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is good. I think of both books as being not exactly dense, but curlicued, if that makes sense: hundreds of tiny flourishes aggregated together to make one grand story. Or like big comfortable houses so full of interesting nooks and crannies that you could happily wander around for days, just exploring.

I put a hold on JS&MN at the library today, and there were lots of copies checked out, for what that’s worth.

Can’t believe it came out in 2004. I’m still thinking of it as a book from “a year or two ago.”

HelenS @@@@@ 57

Nope, you’re not. I’ve broached this topic with at least twenty-five people in the past few days — all big SF/F readers — and of the twenty that had bought and started in on this book, a mere seven had gone on to complete it… only ONE of whom could give me an even vaguely accurate synopsis at this removed date. Glad to hear it’s still being checked out, but I wonder how many of those copies will be returned to the library unread? Maybe you could ask your librarian to take a poll?

Read it when it came out, loved it.

The appearance of copies in second-hand bookstores that I’ve seen has a high correlation to the fact that it was remaindered after a very high print run — either the stores pick it up at the remainder price to resell at a half-price level or individuals pick it up on a whim at a remainder price, bounce, and resell.

However, I don’t think the popularity is overstated. What I have noticed is that many friends who don’t like standard F/SF do like JS&MN (much as they may like Little, Big). So you have to set against the number of regular F/SF readers for whom it did not provide what they wanted the number of “literary” readers who read and enjoyed it.

As for influence — historical fantasy set in a close analogue world to ours with a convincing level of detail and a convincing language is difficult (one reason that we haven’t seen fast sequels from Clarke). Someone who was inspired by Clarke’s book when it came out to write, say, a novel centred around Charles I’s execution with fantasy drawn from English folklore might just be completing his/her research and stumbling through a first draft…

I have pleased memories of JS/MN, which I read around the time it came out. One of the things it did that people have pointed out here that I really wish would get baked into more fantasy yet to come is: it left plenty of space for characters to show as they were. Instead of assuming you would of course dearly love the foibles of the brooding wizard, it laid out the space where he acted, and there you were, to watch and consider. A lot of the joy of the book was being at the side of the ballroom with the author; you were pretty sure she was smirking along with you at the characters out there dancing, but it was worth some thought to assure yourself of that.

RachelHyland @60: did the six who’d read it and couldn’t remember much have a general impression of having liked it, or not? I *do* remember enjoying the experience of reading it — if I’d subsequently been stuck in a vacation rental with nothing else to read, for instance, I wouldn’t say, Oh, dear, not that thing! I’d say oh, good, at least it’s something I am reasonably likely to enjoy re-reading. It’s just that I clearly can’t have had the reaction of how wonderful, I’ve never seen anything like this.

I saw this book on the bookshop shelf and thought I’d give it a go. A foreword by Neil Gaiman and a nice-looking front cover will do that to me.

I finished reading it a few days ago. I got through it in around three days (pretty much non-stop reading, mind you) and I really enjoyed every minute of it. It’s not particularly engrossing, yes the plot meanders a bit and it does take a lot of time, but I just found it nice to read. Like watching a Western on a Sunday afternoon.

An interesting, but rather pretentious review/article. How would you qualify ‘infleunce’ from a single novel, anyway, other than by direct allusion? It may have influenced a lot of contemporary fiction already.