Genre in the Mainstream is a regular series which highlights mainstream literary authors whose work contains genre or genre-like elements. While I’m not claiming these writers for the science fiction, fantasy or horror camps, I am asserting that if you like genre fiction, you’ll probably like these mainstream literary writers too!

Up this time are the unsettling worlds of the Pulitzer Prize winning author Steven Millhauser.

Though the term “magical realism” is bandied about in literary circles to describe fantastical events that occur in what is otherwise a traditional structure, it’s hard to explain the difference between “magical realism” and “speculative fiction” without simply pointing to where certain books are shelved in libraries and bookstores. But if there’s one author that I know for sure without thinking that writes works of magical realism, it’s Steven Millhauser.

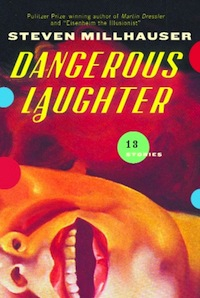

Millhauser’s output is considerable and as such, a much longer scholarly survey could probably be constructed on all the various genre leaning his novels and stories have. But for the purposes of my little column here, I’d like to focus on Millhauser’s most recent 2008 collection of stories: Dangerous Laughter. The book begins with a story called “Opening Cartoon” which describes an epic never-ending chase sequence between an anthropomorphized cat and mouse. An obvious homage to Tom and Jerry cartoon, Millhauser injects pathos and serious drama to sequences of absurd cartoon thrills and spills.

The cat understands that the mouse will outwit always him, but his tormenting knowledge serves only to inflame his desire to catch the mouse. He will never give up. His life, in relation to the mouse, is one long failure, a monotonous succession of unspeakable humiliations….

These humiliations take many forms, like an anvil falling on the cat’s head or a bomb exploding at the last second to reveal a pair of cliché boxer shorts. Millhauser hasn’t really gone full tilt with fantastical stuff in this opening story, but by making a Saturday morning cartoon homage into literature, he starts messing with the sense of what is possible in the various stories that follow.

In the story “The Disappearance of Elaine Coleman” he describes a character who is so neglected by people and the world around her that she literally disappears into nothingness by the end of the story. Similarly, the title story “Dangerous Laughter” describes a deadly game played by a group of teenagers where they literally laugh themselves to death. As a fan of comic books, I couldn’t help but think of DC comics villain the Joker in this story. It was as if Millhauser was meditating on the notion of what would happen if The Joker were real and were inside of each of us.

But two stories explore the realms of near science fiction even more keenly. In the second part of the book, entitled Impossible Architecture, comes a story called “The Dome.” In it certain well-to-do homeowners decide to have their houses encased entirely in trasnparent domes. This is thought to be a passing fad among the more rich erudite in society, but soon it starts to catch on among all economic classes. Soon, entire nations are undergoing doming procedures and eventually the entire world is covered in a transparent globe. What is highly unsettling about this particular story is Millhauser’s ability to make this seems like a historical account of something that has already happened. The reader feels like they should have seen this whole strange thing coming, but they don’t.

My absolute favorite story in this collection however is one called “The Other Town.” Like “The Dome” this story presents itself as a sort of explanation of a fantastical event that the narrator sort of implies we already perceive. A few miles away from a quiet town, another perfect replica of the town exists. This other town is primarily empty, but it is kept totally up-to-date with what is happening in the “real” town. If someone breaks a glass in their home, then that room in the other town will feature a broken glass. In order to accomplish this, the town employs what are called “replicators”; people who make sure everything is accurate on a two-hour basis. Soon, many inhabitants of the primary town to wonder why the other town is there at all. If Millhauser has an answer as to why the other town exists, he isn’t telling.

But is there a reason why reality television exists? Or art for that matter? Millhauser seems to tease at the notion that all replication is on some level self-indulgent, and yet necessary. The other town, for me, serves as a metaphor for how art and entertainment are an emotional necessity for society’s sanity. By actualizing this as a physical place that a society is willing to bend over backwards to maintain, Millhauser is talking about the sacrifices we’ll make for our dreams. And yet, because the other town is just like the primary town, it turns out our dreams are part of our real life.

What doesn’t come across in my descriptions of these stories is the humor of these stories. If you love the ability of fantastical literary conventions to unsettle you and make you laugh a little at the same time, then Dangerous Laughter and other Steven Millhauser books are for you.

Ryan Britt is a regular blogger for Tor.com. He is has also written science fiction commentary for Clarkesworld Magazine. His other writing has appeared with Opium Magazine, Nerve.com and elsewhere. He lives in Brooklyn and is thankful there is no simulacrum Brooklyn.

I wouldn’t call Millhauser magical realist at all. He’s certainly been referred to as a magical realist, but mostly by second-tier reviewers who are loathe to use the word “fantasy” because it brings to mind hobbits or Harry Potter.

The better rank of critics have no problem simply describing Millhauser’s work thusly: ” His tales, whether in the form of stories, novellas, or novels,

manipulate reality, stretching it until it seeps into another

realm–otherworldly, fantastic, and strange.” (that’s a bit from an article in Review of Contemporary Fiction). A quick check of questia shows me no hits for Millhauser and magical realism, though an equally quick Google shows me plenty…mostly from blogs and whatnot.

I’ve been thinking about “magic realism” a bit lately, too, because I was trying to decide whether to use it in reference to Alexander Yates’ Moondogs (which I was thinking would be perfect for this column, actually), and I’m wary to use the term for exactly the reasons you and Nick have set out. (Although I think Moondogs might really fit the label.) I’m not as familiar with Millhauser as you are, but your descriptions of those stories seem more like “fantasy” to me–in the sense of “Could I imagine this story published in, say, Fantasy & Science Fiction like Vonnegut was?”

(By which arbitrary standard I am TOTALLY classifying George Saunders’ “Pastoralia” and “Sea Oak” as fantasy stories.)

@N Mamatas and Ron Hogan

Hmm. You know, there’s a very real chance when I used the term “magical realism”, I wasn’t really thinking too much about it, but instead was speaking sort of emotionally about the relationship that term has FOR ME to Millhauser.

Part of what I hope this little series can accomplish is to open up discussions like these and challenge our notions as to what the various genres are doing(or have done) for serious literature.

Naturally, I might be wrong and my use of “magical realims” to describe these stoires may be a product of me writing a blog and wanting to be able to use quick terms that I feel we all understand. And yet, because the purpose of little articles like these is to break down our understanding of what these quick terms mean, I think the paradox is achieved.

So I guess what I’m saying to N Mamatas is this: Yes, you’re right. and No. And maybe Yes.

:-)

“The Town” sounds like an expansion of one of Italo Calvino’s riffs in “Invisible Cities.” Wouldn’t be surprised at all if that’s where the inspiration came from.