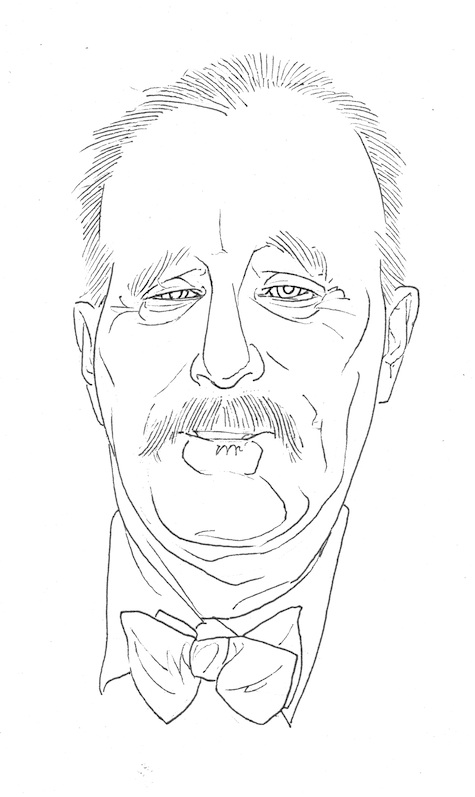

H.G. Wells is considered one of the fathers of science fiction, and if you look at a brief timeline you’ll see why he’s so extraordinary:

- 1895: The Time Machine

- 1896: The Island of Doctor Moreau

- 1897: The Invisible Man

- 1898: The War of the Worlds

- 1901: The First Men in the Moon

So basically for four consecutive years Wells got out of bed on New Year’s Day and said, “What ho! I think I’ll invent a new subgenre of scientific fiction!” And then he took some time off, only to return with a story about a moon landing. If it wasn’t for that gap at the turn of the century, he probably would have invented cyberpunk, too.

To put this amazing streak in some perspective, Wells was born into a very poor family that fell into real poverty during his adolescence. He suffered through a series of Dickensian apprenticeships before he was able to basically study his way up Britain’s social caste system, working at several pupil-teacher positions before winning a scholarship to the Normal School of Science in London and studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley. After finally earning a B.S. in zoology he became a full-time teacher (A.A. Milne was one of his students) and then began writing the speculative fiction that made him famous. But even that wasn’t enough for him.

Take away H.G. Wells’ role as a founder of science fiction, and what’s left? Allow me to paraphrase Tony Stark: Feminist. Socialist. Pacifist. Non-Monogamist. Utopian. Campaigner against racism, anti-Semitism, and fascism. After World War I, he mostly abandoned writing science fiction in favor of realistic social critiques, and spent the last decades of his life as a lecturer and educator, trying to convince people, even as World War II was unfolding, that humanity deserved a better future.

Oh, and he popularized wargaming! He wrote a book called Floor Games in 1911, in which he developed a theory and methodology for playing children’s games with miniatures and props. Wells followed that up in 1913 with Little Wars, which was designed for “boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys’ games and books.” Why would a pacifist develop a wargame? He explains his reasoning in the rulebook, which was quoted at length in a recent New York Times article about gaming:

“You have only to play at Little Wars three or four times to realize just what a blundering thing Great War must be. Great War is at present, I am convinced, not only the most expensive game in the universe, but it is a game out of all proportion. Not only are the masses of men and material and suffering and inconvenience too monstrously big for reason, but—the available heads we have for it, are too small. That, I think, is the most pacific realization conceivable, and Little War brings you to it as nothing else but Great War can do.”

Little Wars popularized the idea of games based in miniatures and strategy with a non-military audience. It led in turn to the development of other role-playing games, and influenced Gary Gygax’s work on Chainmail as well as his later work with Dave Arneson on Dungeons & Dragons, as Gygax writes in the forward to the 2004 edition of the game.

So, having either invented or hugely influenced five different subgenres of science fiction, H.G. Wells also created the modern roleplaying game, and it’s safe to assume that he’s responsible for a huge amount of your cultural life! As an extra birthday tribute, we invite you to listen as H.G. Wells teases his “little namesake,” Orson Welles:

This article was originally published September 21, 2013.

Don’t forget the part where he time-travelled to 1979 San Francisco, fought Jack the Ripper, and fell in love with Mary Steenburgen!

Seriously, I just watched Time After Time last night, simply because of the timing of when it came up on my Netflix queue, and I had no idea it was so proximate to Mr. Wells’s birthday.

But that was a heck of an interview. Wells and Welles, with some ominous foreshadowing about the state of the world in 1940, and a plug for the upcoming Citizen Kane? That’s an amazing piece of radio.

1899: When The Sleeper Wakes – contemporary man in future dystopia

1904: Food of the Gods – superkids

ChristopherLBennett@1: Time after Time is one of my favourite films; the effects are a bit cheesy and it’s all very 1970s, but i just love it. Malcom McDowell and David Warner alone would make it worth watching, but Mary Steenburgen — well, what can I say? The scene on the sofa in her flat is priceless.

@3: Steenburgen has a way of running off with strange time travellers, doesn’t she? First H.G. Wells, then Doc Brown.

It’s a much better movie than I remembered, though you can see Nicholas Meyer imposing his pessimism about the future on Wells the way he later would on Star Trek. It’s hard to reconcile Herbert’s loss of his utopian vision here with the real Wells’s continued utopian writings well after 1893.

And I don’t think I should even try to address the problems with the film’s temporal mechanics and time-machine operation. Then we’d be here all week.

@@.-@: It’s hard to reconcile Herbert’s loss of his utopian vision here with the real Wells’s continued utopian writings well after 1893.

Not at all. He married Amy Robbins in 1895; I’m sure she brightened his outlook considerably. (I mean, seriously: Mary Steenburgen!)

@5: True; if nothing else, the events of the film proved that the future was mutable, so maybe he was just motivated to push even harder for change.

Or, no, wait a minute, maybe they didn’t show that. The event that I thought was changed was actually misreported. So I’m not sure. Never mind.

Yup, H.G. was one Sharp dude.

Can you do a similar overview of Olaf Stapledon? I’ve only recently read his two famous works, First and Last Men and Star Maker and found out that any idea that Wells missed, Stapledon covered, from virtual reality to Dyson speheres (20 years before Dyson!).

Age of War, the 6th episode of BBC Radio 4’s recent Seven Ages Of Science series by Lisa Jardine, mentions HGWells’s The World Set Free (1913) – a story involving what he called “atomic bombs” – in the real-world context of Churchill having read the book before his first public utterance on nuclear weapons in 1926 (listen from 2:00 in the radio programme linked to above).

The Wikipedia article on The World Set Free says “Wells’s novel may even have influenced the development of nuclear weapons, as the physicist Leó Szilárd read the book in 1932, the same year the neutron was discovered. In 1933 Szilárd conceived the idea of neutron chain reaction, and filed for patents on it in 1934.”

@8: So Wells invented one thing we hate as well?

Next year is the centenary of the start of The Great War, aka World War One. Many people will write that it was called “the war to end all war”, but it was HG Wells who came up with that notion in a series of articles published in October 1914 in a book called The War That Will End War. Now that it had started, he wanted to smash German expansionist imperialism so thoroughly that it and anything like it could not rise again.

@@@@@ 9: But I love atomic bombs…

OK, not really. But there’s no denying sf about atom bombs and their aftermath was certainly a popular sub-genre, eventually… though 30 years and more after Wells’s novel, mostly.

Worth bearing in mind that Wells was also a bit of a charmer. He was a member of a number of London clubs including the Savile, where according to club legend the father of a girl he seduced sat upstairs with a loaded shotgun for several years waiting in case he came back in the front door.

HG Wells and I were born 101 years and one day apart.

I agree about Time After Time. It has one of the great, punch-to-the-gut lines in cinema. Jack the Ripper says something to the effect of, “In our time I was a freak, here I’m an amateur,” while watching television!

Wells is understandably horrified.

Wells was a genius and crucial to the creation of SF.

OTOH, his biography is a bit more complex than the article implies.

To begin with, he wasn’t born into “a very poor family”. His parents were lower-middle class, and ran a shop. The shop did badly and money was always short, but this wasn’t anything remotely approaching what Victorians would have called “real poverty”.

Real poverty in that period involved getting thrown out of your house, not having any money for food or shoes, and having to go into the Workhouse. Agricultural laborers or dock-wallopers were poor. The Wells family just wasn’t very affluent.

His mother spent her later working life as a ladies’ maid in the country house of a gentry family, which was a long, long way from a really bad job (like being the single “slavey” in a clerk’s household), and Wells got an education and comfortable living surroundings.

He was apprenticed as a draper, a lower-middle-class commercial occupation; again, modest but not poverty. The family then got him into the teacher-training stream, which was standard for bright young men of his social background.

Up to that point, his life was fairly routine, nothing extrordinary. It was what he did afterwards that was marvelous.

“Feminist. Socialist. Pacifist. Non-Monogamist. Utopian.”

— well, he was certainly a non-monogamist. Or to put it another way, he was a tomcatting bastard who used the ideology of “free love” as an excuse for being extremely selfish and hurting people’s feelings. This is not the most pleasant part of Wells’ life, particularly as he got into middle age.

Utopian? Well, yeah, but in the immortal words of Inigo Montoya, “You keep using that word…”

In his wildly successful non-fiction bestseller ANTICIPATIONS, his outline of his ideal future world-state, for example, he goes on at some length how the scientist-engineer rulers of his World State will engage in “mercy killing” of the “unfit” (who he estimated at about half the popultion) and sterilize others.

So that they would promote:

“the procreation of what is fine and efficient and beautiful in humanity—beautiful and strong bodies, clear and powerful minds … and to check the procreation of base and servile types … of all that is mean and ugly and bestial in the souls, bodies, or habits of men.”

And, to quote Wells again: “those swarms of blacks, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people … will have to go… it is their portion to die out and disappear.”

He wasn’t all that keen on Jews, either.

In other words, he was a fairly standard Edwardian eugenicist and social-Darwinist (leftie subvariety), though the above words raised some eyebrows even at the time. They were meant to be “advanced”, shocking to what he and other young firebrands considered soppy mid-Victorian sentimentality.

He was very much a man of his time and the zeitgeist of his region and generation. There’s no need to get retrospectively hysterical about that; times change, people change (he got a lot more mellow later in his life), and it doesn’t in the least detract from his massive literary achievements.

But let’s not pretend that the young Wells would be regarded as -salonfahig- these days.

He also predicted tanks, aerial bombardment, remote command and the date of WWII. His ambitions were big, his flaws were bigger. Either way he’s the most successful future forecaster of all.

Wait. I thought H.G. Wells was a woman who was trapped in suspended animation in Warehouse 13 for years and years . . ..

In “The Sleeper Wakes”, Wells also invented such things as a 3D printer for clothes and the DVD player (sort of), a television with cartridges for viewing news, entertainment and educational programs.

Still, as @joatsbuddy pointed out, the man was no saint or intellectual god of rationalism. Toward the end of his life Wells became obsessed with the greatest hokum of his day, Spiritualism. Some biographers suggest that when his former friend, Houdini, mounted a lifelong campaign to expose all spiritual mediums as money-sucking charlatans, Wells essentially hired a thug to rough him up, resulting in Houdini’s death.

At least he wrote well. Many of his short stories feel like novels.

You forgot Ludite as he didn’t actually like technology which is why I always laugh when people argue about how science fiction should never point out problems with technology … obviously they have never read Wells. His books contained spiritualism as well which call it a hokum if you like it is why when people get upset with its inclusion in sci-fi (like say the new battle star galactica) I laugh. Been there from the beginning.

Never knew he was a communist amazing after pulling himself up by his boot straps why he would want a world where people didn’t have to do that and could go up levels without work. Sigh….ah well suppose he did believe people would work regardless believing good about humanity even if wrong is I suppose better than the alternative.

WRT Free Love (or tomcatting around), for many years Wells was the lover of Rebecca West. They started when she was 20 and he was 40, and kept on until she was in her thirties. They had a child together — Anthony West, who grew up to be a respectable novelist and writer in his own right, though largely forgotten today. They stayed friendly after the affair stopped, though West was very critical of Wells’ politics and world-view.

(If you don’t know who Rebecca West is… ooh, you’re in for a treat. Dig up some of her essays, or her journalism on the Nuremberg Trials. A great writer, and a remarkable human being.)

Doug M.

Oh, and also there’s this anecdote:

Journalist Vincent Sheean tells this story from 1940. At the height of the Blitz, with German bombs raining down on London, a group of literary friends were having lunch at the London townhouse of Lady Sibyl Colefax…

“On another day further on, in the full bombing season, there was a

spirited and talkative lunch at Sibyl’s. The company included H.G.

Wells, Somerset Maugham, Bruce Lockhart, Moura von Budberg and Diana

[Duff] Cooper. Mr. Wells was being particularly malicious about God,

one of his favorite themes (a propos of a prose poem by Francois

Mauriac which Mr. Maugham had produced). As he held forth with his

usual perky, cheerful insistence, with many a ‘that sort of thing’ and

‘don’t you know’, the bombs began to thunder down. Sibyl got a little

nervous. ‘I don’t like this a bit,’ she said. ‘What if a bomb should

land here now? It’s much too good a bag for the Germans,’ she said,

nodding toward the literary gentlemen. ‘Why don’t we just go to the

shelter? It’s not much good, but it’s better than just sitting

here.’ There was a little flurry of discussion and she was voted

down; a minute or two later, when the noise seemed to be coming very

near, she brought it up again.

“‘I refuse to go to the shelter,’ said Mr. Wells with happy

perversity, ‘until I have had my cheese. I’m enjoying a very good

lunch. Why should I be disturbed by some wretched little barbarian

adolescents in a machine? This thing has no surprises for me. I

foresaw it long ago. Sibyl, I want my cheese.’ [Wells at this time

was about 74 years old.]

“Sibyl was obliged to give him his cheese and I suppose we all

reflected the same thing, which was that, indeed, this very Mr. Wells

had foreseen aerial warfare even before the invention of the airplane:

somehow a startling fact as we sat there, and listened to the

explosions. Sibyl’s invaluable factotum, Fleming (a severe and

elderly woman who always gave Noel Coward an extra helping of

everything, particularly puddings) came into the room and put up the

wooden frames which hid the windows. ‘At least we may as well be

spared the effort of dodging the broken glass,’ Sibyl said. She had

lost the glass out of her windows three or four times in the past

weeks and had some feeling on the subject.

“[So we] sat there under the electric lights at midday, with the

windows blocked off, while Mr. Wells resumed both his cheese and his

discourse.”

Now, H.G. Wells was a complex character, and he could be a huge jerk

sometimes. But you have to respect this. The man wanted his cheese.

And he had the combination of physical courage and puckish smartassery

needed to sit there while the bombs rained down.

N.B., Wells would survive the war, dying in bed at the age of 80 in

1946.

Doug M.

@23 Re the year 1940: In THINGS TO COME, the 1936 film adaptation of Wells’s “The Shape of Things to Come,” the next World War begins in December 1940 with a surprise air attack that devastates the British fleet, followed by severe aerial bombardment of British cities. One wonders whether Wells had this in mind at the time.

I would so love to see a film version of “War of the Worlds” that is actually set in the same time period as the book itself.

@25/Brenda A.: There was a faithful, low-budget, period-piece film adaptation of the novel released in the same year as the Spielberg version. It’s generally considered to be awful, on the level of an Ed Wood movie. However, in 2012, the same director re-edited and reworked it into a faux historical documentary, War of the Worlds: The True Story, which has been far better received.