There used to be a genre called “gothics” or “gothic romances.” It thrived through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, and vanished sometime in the early seventies. It died at the time when women reclaimed their sexuality, because one of the things about the gothic is the virginity of the heroine, who is often abducted but never quite violated. Gothics don’t work with strong sexually active women, they need girls who scream and can’t decide who to trust. They also work best at a time period where it’s unusual for women to work. They’re about women on a class edge, often governesses. The whole context for them is gone. By the time I was old enough to read them, they were almost gone. Nevertheless, I have read half a ton of them.

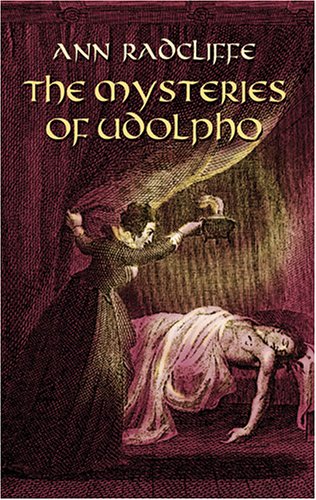

The original gothic was Mrs Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). I haven’t read it, but I know all about it because the characters in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817) have read it. Jane Austen didn’t write gothics—far from it, one of the things she does in Northanger Abbey is make fun of them at great length. The gothic and the regency were already opposed genres that early—they’re both romance genres in the modern sense of the word romance, but they’re very different. Regencies are all about wit and romance, gothics are all about a girl and a house.

The canonical gothic is Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1850). It has everything that can be found in the mature form of the genre. Jane goes as a governess into a house that has a mysterious secret and meets a mysterious man who has a mysterious secret. That’s the essense of a gothic, as rewritten endlessly. The girl doesn’t have to be a governess, she doesn’t even have to be a girl (The Secret Garden is a gothic with a child heroine, and I have a theory that The Magus is best read as a gothic and that’s a lot of why it’s so weird), the man can be the merest token, but the house is essential and so is the mystery. The mystery can be occult, or mundane, it can be faked, but it has to be there and it has to be connected to the house. It’s the house that’s essential. It can be anywhere, but top choices are remote parts of England, France and Greece. If it’s in the US it has to be in a part of the country readers can plausibly be expected to believe is old. The essential moment every gothic must contain is the young protagonist standing alone in a strange house. The gothic is at heart a romance between a girl and a house.

My two favourite writers of gothics are Joan Aiken and Mary Stewart.

Joan Aiken wrote millions of them, and I’ve read almost all of hers. (I was sad when I found out recently that some had different UK and US titles, so I’ve read more of them than I thought.) There’s a character in Margaret Atwood’s Lady Oracle who writes gothics as hackwork, and I wonder whether Aiken did this for a while. In any case, she wrote tons of them, and some of them are very standard kinds of gothic and some of them are very peculiar. They’re kind of hard to find, especially as very few people read gothics these days. But she has one where both protagonists are dying (The Embroidered Sunset) and one that deconstructs the genre much better than Atwood does (Foul Matter) by being about someone who was the heroine of a gothic (The Crystal Crow aka The Ribs of Death) years before. (There’s also an interesting deconstruction in Gail Godwin’s Violet Clay, whose protagonist paints covers for gothics. She imagines how the marriage of the governess and the lord works out in the long term.) Aiken comes up with all sorts of reasons for the girl to come to the house—singers, governesses, poor relations, necklace-menders. She’s quite conscious that the whole thing is absurd, and yet she has the necessary sincerity to make it work.

Mary Stewart wrote fewer of them. I fairly recently came across Nine Coaches Waiting, which is about as gothic as gothics get. The girl is a governess, she has a secret of her own, she’s concealed the fact that she speaks French. The house is in lonely Savoy, it’s a chateau. Her pupil is the count, but his uncle manages the estate, and there are several mysteries and the governess can’t decide who to trust. It’s just perfect. Her Greek ones (especially My Brother Michael) are also great, and so is The Ivy Tree. Touch Not the Cat is even fantasy, there’s family inherited telepathy.

So why do I like these? They used to be a mainstream taste, selling in vast quantities, and then they melted away as women became more free and more enlightened. Why am I still reading them, and re-reading them? There’s a character in Atwood’s Robber Bride who says she reads cosy mysteries for the interior decor. I am very much in sympathy with that. I don’t want to read rubbishy badly written gothics, but give me one with a reasonable ability to construct sentences and I know I am at the very least going to get a moment with a girl and a house, and descriptions of the house and food and clothes. I do like the scenery, and it is frequently nifty and exotic. But that’s not enough.

I’m definitely not reading them to be swept away in the romance—the romances are generally deeply implausible, though of course the heroine ends up with the guy revealed by fiat to be the hero, the same way a Shakesperean sonnet ends with a couplet. I’m not much for romance, in books or in life. To be honest, I don’t find very many romances plausible—I think there are two of Georgette Heyer’s romances I believe in, and one of Jennifer Crusie’s.

What I really get out of them is the girl and the house. The girl is innocent in a way that isn’t possible for a more enlightened heroine. She isn’t confident, because she comes from a world where women can’t be confident. She may scream, she is alone and unprotected, and she comes from a world where that isn’t supposed to happen. Things are mysterious and frightening, she is threatened, and she’s supposed to fold up under that threat, but she doesn’t. There’s a girl and a house and the girl has more agency than expected, and she doesn’t fold in the face of intimidation, or you wouldn’t have a plot. The heroine of a gothic comes from a world that expects women to be spineless, but she isn’t spineless. She solves the mystery of her house. She has adventures. She may be abducted and rescued, she may scream, but she earns her reward and wedding and her house—the hero is her reward, she is not his. She comes from this weird place where she isn’t supposed to have agency, she isn’t even really supposed to earn her own living, and she heads off into the unknown to do so and finds a house and a mystery and adventures and she acts, and she wins through. Some heroines are born to kick ass, but some have asskicking thrust upon them. The heroines of gothics discover inner resources they did not know they had and keep going to win through.

I have no idea if that’s what the readers of gothics from 1794 until the dawn of second wave feminism were getting out of them.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

But what about Barbara Michaels? She was writing books about women and houses up until the mid-90s, when she decided to retire that pseudonym (she is still writing as Elizabeth Peters). My favorite three books of hers have characters in common but but there is a house only in the first (Ammie Come Home, Shattered Silk, Stitches in Time), but all three deal with women in a transitional place in their lives. Most Barbara Michaels books start with a heroine in transition, actually. They’re all set in the US South, most have houses, and spooky atmospheric stuff that is sometimes paranormal and sometimes not.

I have a Theory about gothic novels, romantic suspense, and urban fantasy/paranormal romance, but I haven’t had time to do the reading necessary to confirm my theory–which involves female agency but also social anxiety around where women belong in society. Someday…

I’m going to have to nitpick with you–the first gothic novel is arguably The Castle of Otronto, which came 30 years before Udolpho.

Re: the decline of gothics, I would argue that the genre is in full force today–just not in print. Horror films, particularly Japanese and Korean horror, often perfectly encapsulate the gothic experience. J-Horror and K-Horror frequently include (just to name a handful, this is a dangerously broad brush I’m using) belief in ancestral spirits and ghosts tied to specific homes or places, and an obsession with virginity (and submissiveness) coupled with the perversion of female sexuality (and aggressiveness) as something disturbing and horrific.

Oh, and the one gothic I can think of that doesn’t involve a girl and her house is The Monk, which is easily the most disturbing of the gothics I’ve come across. Great stuff, though.

Eilatan: I haven’t read Michaels, but it doesn’t surprise me that someone was still writing them — it’s just that there used to be a whole genre with lots of them being published every month.

Thanks– much to think about there, especially about who gets rewarded.

Fiction about houses is a large category– there’s an emotional difference between inheriting a weird house and going to a weird house which belongs to someone else, but both are strong bases for fiction.

Have you read Alcott’s A Long Fatal Love Chase. I don’t think it’s a gothic, but it’s an engaging novel of a sort which I don’t think could get published now.

I was just about to mention Michaels. What makes her books especially fun is that you can alternate between a classic Gothic from Michaels followed by an Elizabeth Peters novel poking fun at the entire genre. (I’m particularly fond of the Vicky Bliss series, but both Legend in Green Velvet and Devil-May-Care are hilarious Gothic satires.)

We may also be seeing fewer Gothic novels because of the death of the highly prolific Victoria Holt/Jean Plaidy/I forget the other pseudonyms in the 1990s. She was responsible for three titles a year alone.

I think Carol Goodman could be classified as a contemporary Gothic writer, or at least someone who uses some of the trappings of the genre.

No love for Clara Reeve by “Leonie Hargrave,” aka the late great Thomas M. Disch? It’s both a celebration and subversion of the genre.

Something I’m looking forward to is THE EVIL AT PEMBERLEY HOUSE by Philip Jose Farmer and Win Scott Eckert, which is due out the next week, I think. It’s apparently Farmer’s take on gothic romances, which should be very interesting. The heroine’s name is Patricia Wildman, and, if you know Farmer, you know that the similarity to Pat Savage isn’t cooincidental. And there’s an iconic Heroine Running Away from the Mansion cover by Glenn Orbik.

I once read The Shrouded Walls, by Susan Howatch (which was NOT a sex-free gothic) and I was blown away. I immediately ran to the used bookstore and bought all the gothics I could find. it turned out, however, that they were all crap and I just lucked out on my first shot. I still haven’t give up, though. Thanks for listing some names I can trust!

MariCats, the Vicky Bliss books are my very favorite. The one that came out last year was complete and utter fan-service, but it was a tremendous amount of fun nonetheless. MPM is one of my all-time favorite authors and I was really sad when she stopped writing under the Michaels name.

FWIW, Romantic Times still has a romantic suspense section in the magazine–there were six titles reviewed in the November issue, but there is likely some overlap with the mystery section and I’m not familiar enough to pick out which ones are gothicky and which ones aren’t based on title alone. I think there’s been some evolution/re-naming in the genre, and I know there are still books coming out along those lines (for example, this month there’s a book called Audrey’s Door about a woman who is leaving a bad relationship and rents a haunted apartment–I can’t really recommend it, though, it bounced off me in some pretty bad ways).

The best of the modern gothics is the Thirteenth Tale by Setterfield. IT has it all the out of work writer (governess) the mysterious house and owner and many many secrets. I highly reccommend it to all gothic lovers.

Also can’t say gothic without Rebecca.

Once upon a time, in my teens (in the early 1970s), I belonged to the Doubleday Book Club — not an SF book club, but mainstream. Every so often I accidentally got the monthly feature, because I’d forgotten to send in the “don’t send me” notification. The most memorable of those was the two-in-one volume of Kirkland Revels and Mistress of Mellyn, both by Victoria Holt. I’d never read a Gothic romance before, and was barely familiar with the romance genre in general.

The books were exceedingly puzzling to me. I kept trying to locate them in time; I’d originally assumed they were contemporary, but kept moving back and back. And the people in them seemed to be remarkably isolated from anyone else in society. Eventually I learned more about the genre and the conventions thereof, and the books no longer seemed so interesting and mysterious. But I doted on the pair of them for quite a while.

Decades later, I tried to read one of Jean Plaidy’s novels set (IIRC) during the Plantagenet period, and I couldn’t get through it because the prose was so incredibly clunky. I haven’t read the Holt novels (some author, different pseudonym) since my teens, so I don’t know if I would have the same problem now. But then, they were well worth reading — possibly at least in part because I read them with the SF eye, and they were alien cultures.

If the essential thing is having a girl and a house, does that mean Coraline is a modern-day Gothic for kids?

Smog1: Ah, Rebecca. That kind of exemplifies my point about the house, actually, because she still has the guy at the end, but it’s tragic because she’s lost the house. Manderley. The girl doesn’t even have a name, but Manderley’s named in the first line of the book!

Carbonel: I was astonished when I found out that Holt was Plaidy, because I always found Holt readable and had problems getting into Plaidy. I kept getting Plaidy out of the library because her books looked as if they’d be interesting, and then I wouldn’t be able to get interested in them. She must have used a completely different prose style — I wonder how she did it?

When I was a teenager I devoured Victoria Holt, and then Barbara Michaels. I remember BM’s heroines being stronger and less wilting flower than VH’s, although all of BM’s always seemed to be choosing between two men who were very similar in each novel.

In college I was frustrated with the heroines in 18th-19th century novels and the ones in the gothics seemed a lot more active and like you said, they might scream or faint but they didn’t fold, they were investigators and explorers. A big part of it for me was the girl vs. the big old house.

Rebecca is the ultimate girl vs. big old house and a battle of wills between two women. They’re fighting over the *house* more than the guy if you ask me.

Your friendly neighborhood 18th c. graduate studies refugee here!

Yes, *The Castle of Otranto* was the first novel (or, in the era’s parlance, the first romance) that labeled itself as Gothic. *Udolpho*’s innovation largely had to do with de-mystifying the supernatural elements of the genre — the Scooby Doo effect, as it were. In some ways this made the genre a lot less fun.

*The Monk* gets lumped in as a gothic novel for a lot of convincing reasons, but ultimately it’s kind of its own, weird, disturbing thing.

But for kick-ass women, one would be hard-pressed to beat Charlotte Dacre (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Dacre)and her totally nutty novel Zofloya. It’s as problematic a novel as they come — the MC has an affair w/ Satan who naturally takes the form of an African Muslim — but it’s a rip-roaring read, and a fascinating counterpoint to Radcliffe’s goody-goody heroines…

Gotta disagree about The Monk — if you consider the girl to be both the innocent virgin Antonia and Agnes, the dastardly-treated novitate and secret wife, and the house to be a combo convent/abbey, then you’ve got both necessary details.

skinnyiain @@@@@ #12: gosh, now I want to re-read _Coraline_.

Rachel Brown has some fabulous reports of extremely cracktastic Gothics over on LiveJournal.

#7: Bill, thanks for the shout out. THE EVIL IN PEMBERLEY HOUSE is out now, either from Amazon or direct from Subterranean Press.

Radcliffe also wrote ‘The Italian’ that kind of mirrored Lewis’ The Monk. I took a class where we read some of the books in this tradition. The Monk, Zofloya, The Italian, and others. We spent a long time talking about how each of the novels used and abused the conventions, one of which was the sense of the sublime and the unknown. Almost without fail, there was some variation on the phrase “words cannot describe” to begin a sentence somewhere in the books.

On a totally unrelated note, you just can’t beat the falling statue’s head and helmet in Castle of Otranto. Kind of a goofy, slapstick scene where I wondered if the guy had really be squished.

#12: Like that idea. It implies that, like Coraline, gothic heroines need the fear and inherent inferiority (in terms of experience and position of power) to highlight their strength and courage. Also, I realise that I do enjoy being scared shitless by dark houses and talking animals.

‘…a world that expects women to be spineless, but she isn’t spineless. She solves the mystery of her house. She has adventures.’

True, that.

The plot devices of gothics are contrived and unbelievable, but somehow their average, non-descript heroines are more sympathetic than ‘spunky’ modern female characters I read about in fiction and romance novels.

Will catch up on the other gothics suggested. But I urge people to stay away from Georgette Heyer’s attempt at a gothic, Cousin Kate, which is just insane and muddled-up.

Which two Heyer romances did you believe in? I also liked the M.M. Kaye “Death in [Exotic Place]” books, which are gothicky.

BethMitcham: A Civil Contract and The Unknown Ajax. With half a point for Cotillion if you read it as if “not in the petticoat line” means “gay”.

Had to read both The Castle of Otranto and The Mysteries of Udolpho in high school English. Otranto was better because it was shorter, plus the wacky stuff like the giant ghostly helmet.

It also made me much more thankful for the invention of quotation marks and I am not happy with some modern writers who seem to have ditched that as a newfangled luxury or something.

If gothics are still around, they have gone into hiding in the young adult section. John Bellairs, in his long career, wrote nothing BUT gothics, beginning with the delightful “The House with a Clock in Its Walls.”

There was never a girl, but there was always a boy (perhaps a girlish boy), a house, and a mystery.

Dean Koontz, in his one book on writing, described how an aspiring author need never take a desk job, but simply crank through a few gothics in a month or two for the same amount of income. His advice seems rather dated now …

I dunno, I always felt that Radcliffe took herself so damned seriously, hence my love for the far more depraved The Monk. Lewis understood that no one really cares about the heroine – it’s the evil that we love! – in a way that I don’t think Radcliffe fully appreciates. Also she sometimes confuses telegraphing everything as a good substitute for suspense.

I know it’s not gothic, per se, but no love for Melmoth The Wanderer? It and The Monk I think are responsible for many streams of modern suspense or horror fiction.

Most of the few gothic romances I’ve read have been Aiken’s, which I picked up because of her name on the spine. (I grew up reading her Dido books, and someone read Nightbirds on Nantucket to me before I was old enough to remember–and Not What You Expected may be my favorite single-author anthology of all time.) I didn’t like them nearly as well as her other books, but now that I think about it, I might just have been the wrong age for them. I’ll give them another try sometime.

I’d disagree with categorizing The Secret Garden as a gothic novel with a child protagonist. It dresses up as a gothic initially; then expands and transforms as the protagonist grows and changes.

Rereading ‘Paladin of Souls’ reminded me of this thread. A woman who is more powerful than she seems, a house with a mysterious secret, a touch of magic and the supernatural and with the hero represented as a reward offered to the heroine – it has all the hallmarks you describe for a Gothic novel.

But then given that Bujold describes Charlotte Bronte and Georgette Heyer as being among her inspirations for some of her books, it’s probably not sheer chance.

If the esential factor of the gothic is the relationship betwen the girl and her house. This surely comes to its logical conclusion in James Stoddard’s The False House.

Hmmm, I now desperately want to write a subverted gothic. I suppose I ought to read a few of these first….luckily these suggestions seem like the best way to get a crash course!

@19 grilojoe77: Interesting, I took a class just like that in college! It was a Narrative Lit class that happened to focus on Gothic literature that semester. Aside from The Italian it included Dracula, “The Fall of the House of Usher”, a number of stories by Kafka, Lady Audley’s Secret (loved it!), Heart of Darkness, The House of the Spirits, and several others I can’t recall. We also talked about the sublime and deconstructions, and the class was fascinating.

@24 ELeatherwood: Thank you! John Bellairs’ books hooked me as a kid and I still love them today, and they are so wonderfully Gothic.

I have both The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Castle of Otranto. Someday soon I will read them.