The term “future history” was coined for editor John W. Campbell to describe a series of stories Robert Heinlein was writing for Astounding Science Fiction magazine in the 1940s. As used in the science fiction genre, the term implies more than just a series of stories set in the same universe. The term “future history” is applied to a series that spans an extended period of time. In fact, authors of future histories invariably report it is necessary to write down an outline of the events and changes to society and technology, which occur during various periods of the timeline. Heinlein started this trend with his famous chart. Other future histories include Poul Anderson’s Technic Civilization, Cordwainer Smith’s Lords of the Instrumentality, H. Beam Piper’s TerroHuman Future History, Alan Dean Foster’s Humanx Commonwealth, and Larry Niven’s Known Space.

A Niven Reading Experiment

“Spike” MacPhee (one of this article’s authors) ran the Science-Fantasy Bookstore in Harvard Square, Cambridge Massachusetts, from 1977 to 1989, and so was able to observe people’s reading patterns. In 1977, as a new bookstore clerk, he had many duties, but also time to observe human behavior puzzles. One of these was the case of readers new to Larry Niven’s worlds, who started to explore them by first buying Ringworld. Why then did only one-third of them try more of his books? The normal author continuation rate, he had observed, was roughly one-half. How could he improve this rate for Niven?

He thought the problem through: Authors tend to build their future histories by starting with short stories and novellas published in science fiction magazines. As they gain proficiency and confidence in their storytelling skills, they move on to writing novels as they acquire a marketable brand name with science fiction book editors at the large publishing houses.

Contemporary readers delight in each new addition, both to the depth and detail of the creator’s universe, as well as the fleshing out of already-encountered characters, cultures, and events. Later readers don’t share in that organic progression of tales as the author spins them out.

An ongoing debate for readers who didn’t read each story when first published is “in what order should I read all the stories—internal chronology, or do I read them in the order written?” The answer varies from reader to reader, depending on the availability of those stories, and/or desire to follow the author’s timeline or order of creation, as well as the ease of first introduction to a detailed universe. Often, random chance rather than a deliberate decision decides how a reader encounters an author’s words and worlds for the first time: a library shelf, a short story anthology with one story by that author, a friend’s suggestion, even a yard sale purchase.

Readers tend to buy novels, rather than short story collections or science fiction magazines, by a ten-or-twenty-to-one ratio. They often enter a future history by way of a novel that makes use of an existing background that is entirely new to them. Authors and editors strive to make each story or novel self-contained, so that a reader can start anywhere and enjoy their future history. That wasn’t happening as much with Ringworld.

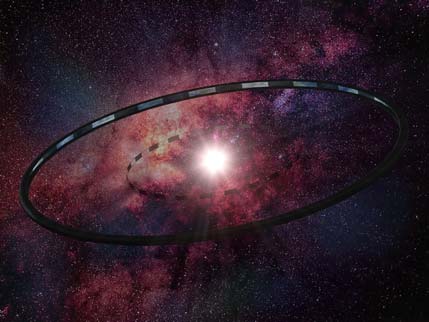

Larry Niven’s Ringworld was his third novel, and it achieved the rare distinction of winning both the Hugo and Nebula awards for Best Science Fiction Novel. So, many more science fiction fans first encountered Niven by browsing their way through the award-winning novel lists, or seeing Ringworld’s book cover proclaiming its prestigious awards, and then buying it.

It seemed to “Spike” that he should suggest to readers that they try a different Niven book first, as an introduction to Known Space. He tried out his theory: Of a sample set of about 60 or so readers, he got them to first try the Neutron Star collection before attempting Ringworld. Doing so improved the sample set’s desire to continue on to other Known Space books—from one-third to approximately two-thirds.

It seemed to “Spike” that he should suggest to readers that they try a different Niven book first, as an introduction to Known Space. He tried out his theory: Of a sample set of about 60 or so readers, he got them to first try the Neutron Star collection before attempting Ringworld. Doing so improved the sample set’s desire to continue on to other Known Space books—from one-third to approximately two-thirds.

So, if you have not yet read Ringworld, we strongly urge you to do the same. Readers trying out a new author for the first time do not usually search for an author’s out-of-print books, but we hope to persuade you to make an exception in this case. We’ll make it easy for you: Copies of Neutron Star can be found through Addall.com’s used book search.

Of course, we are not going to insist you start with the Neutron Star story collection. We promise the Thought Police will not arrest you should you plunge directly into Ringworld. In fact, David “Lensman” Sooby (this article’s other author) became a fan of Known Space by doing exactly that! But you’ll get more out of Ringworld if you read the Neutron Star collection first. (Trust us.)

The Back Story of Ringworld

The novel contains numerous references to previously published Known Space stories, which form the “back story” of Ringworld. These include:

World of Ptavvs: This novel introduces the Slavers (aka Thrintun) and the ancient Slaver Empire. It also introduces the Bandersnatchi, which also survived from that era along with Slaver technologies, i.e., stasis fields and Slaver disintegrators. Both are important technologies in Ringworld. Sonic stunners also appear in several later Known Space stories.

“The Soft Weapon” introduces the Puppeteer character Nessus and serves as a good primer on the warlike Kzinti, so important to understanding the background of Ringworld. The Puppeteer migration is described, and the Slaver technologies of stasis fields and variable-swords are explored. All of these appear in Ringworld.

“There Is a Tide” introduces Louis Wu, and tells of his first contact with the Trinoc who became ambassador to Earth, as mentioned in Ringworld’s first chapter.

“At the Core” introduces the concept of the Core explosion, central to Louis’ motive for agreeing to join Nessus’s expedition. It introduces the starship Long Shot and tells of the beginning of the Puppeteer migration.

“A Relic of the Empire” introduces various species of plants that have survived from the Slaver era, like the Slaver sunflowers, which also appear in Ringworld.

You will also find in Ringworld references to places, species, and technologies introduced in “The Warriors” (Kzinti), “Neutron Star” (General Products hulls), “Flatlander” (Outsiders), “The Ethics of Madness” (autodocs), “The Handicapped” (flycycles), and A Gift from Earth (Plateau and its Long Fall river).

But that’s not all. There are other references to stories outside the Niven canon. These include Alice in Wonderland (the Cheshire Cat and Bandersnatchi—a reference to the poem “Jabberwocky”) and Dante’s Divine Comedy, which Niven later explored with co-author Jerry Pournelle in two novels unrelated to Known Space: Inferno and its sequel, Escape from Hell.

Now, we are not suggesting that you should read World of Ptavvs and all the other stories mentioned above before reading Ringworld. But most of the relevant stories are in Neutron Star, and if you enjoy that collection, then you will then have enough background to precede directly on to the wonders of Ringworld.

A less satisfactory and narrower (but in-print) introduction to Known Space is the more recent Crashlander collection. Less satisfactory because it omits “The Soft Weapon” and a few other stories mentioned above. Worse, it has massive spoilers for Ringworld. If you do choose to start with Crashlander, we recommend you skip the framing story “Ghost,” and stop before reading “Procrustes,” until after first reading Ringworld. You’ll be glad you did!

* * * * *

More about the races, technologies, planets, places, and history of Ringworld and Known Space can be found at The Incompleat Known Space Concordance. Readers new to Known Space are encouraged to visit the “Reading Order” page. Another notable site is Known Space: The Future Worlds of Larry Niven.

Bruce “Spike” R. MacPhee is stranded at the bottom of a pointy well, and passes the time (which is flowing a billionth of a second slower than open space due to gravity affecting the local shape of space) reading SF based on physical laws or modifications thereof. Along with Jerry Boyajian and Larry Niven, he wrote the entries for the first Known Space Timeline that appeared in the 1975 Tales of Known Space collection.

David Sooby, who goes by “Lensman” online, was afflicted with an obsession with the Known Space series when he discovered Ringworld in 1972. He never recovered, and the depth of his madness can be seen at The Incompleat Known Space Concordance, an online encyclopedia for the series, which he created and maintains.

This is so helpful! Having just finished Stars and Gods, I agree with Ringworld being approachable best by existing fans. Thank you for the tips. I’ll be looking for a copy of Neutron Star now. :)

An alternative to searching for out-of-print copies of _Neutron Star_ (no, you can’t have mine! :) ) might be to get the short stories as ebooks.

Fictionwise has quite a few of them:

http://www.fictionwise.com/ebooks/a41/Larry-Niven/?si=0

(Lensman smacks self on forehead) Thank you, RMGiroux! I wish I had thought to check for availability of e-book copies before submitting that article.

Wait, just to be sure of the statistics here. Readers who bought Ringworld went on to buy a second Niven book only one time in three, but those who bought Neutron Star went on to buy Ringworld, and then a third Niven book, two times out of three? That would be the proper comparison to make.

Because getting people to buy Neutron Star as their first Niven book might well result in the people who went on to buy Ringworld as their second book being likely, two times out of three, to buy a third Niven, without anything having changed. We aren’t explicitly told whether one third or two thirds of the people who bought Neutron Star first ever bought a another Niven book, including Ringworld.

I usually hand people a copy of Protector, because it is tightly written, and doesn’t really rely on knowledge of previous continuity.

Del, this was my experience on a limited dataset. What I meant to communicate was that for people whose first Niven book was Ringworld, only one-third tried another. If Neutron Star was their first Niven book, two-thirds of them tried another book by Larry.

-Spike MacPhee

That’s the cover of the copy of Neutron Star I have. Heck, I might have even bought it from Spike. I was in the Science-Fantasy Bookstore a lot back in the day. I still miss it.

I read Ringworld first, loved it, then enjoyed all the “Oho!” moments that came from reading all the other Known Space books and stories.

Yet another alternative to Neutron Star, albeit one involving a deeper commitment to Niven’s works, would be to look up N-space and Playgrounds of the Mind. It looks like one is in print and the other isn’t, but they might be worth checking the library for. They have most of the Known Space short stories, plus plenty of others, and some of Niven’s commentaries as well. My enthusiasm for Niven’s novels has diminished with time, but his short stories are fantastic.

Oh, I see. I thought you were saying reading Neutron Star first made Ringworld more likely to make a Niven reader out of readers than reading Ringworld first, when what you actually meant was simply that Neutron Star itself had a better record as a starter Niven. Maybe it’s just a better book.

It has certainly been said by many that Niven’s strength is in his short stories more than his novels. If so, then clearly Ringworld is a marvelous exception. But then, so is The Mote in God’s Eye, Lucifer’s Hammer, and The Smoke Ring… so IMHO it’s not much of an exception. My own list of “10 favorite Niven stories” contains five short stories and five novels.

I started out reading Niven’s Neutron Star in an anthology in my High School’s library, enjoying the physics involved.

(IMHO, Larry Niven’s two great strengths are his “hard science” and his aliens, even though he does tend to get stereotypical after a while)

Then I found Protector, and after that, Ringworld …

GGcGceGceGceGcecegecGGGc!

let the games begin!

Larry Niven’s two great strengths are his “hard science”

Which he often got wildly wrong [1] (although often in an interesting way). Rock is fluid at planetary scales so neither Mountlookatthat or Jinx can exist in the forms they do; for that matter there’s no way to have a habitable planet around Sirius A because such a planet would have its orbit disrupted by Sirius B (not to mention the effects on such a planet as B, which used to be considerably more massive than A, evolved from a main sequence star to a white dwarf) or the issues raised by the estimated age of the system (a couple of hundred million years) and when it was colonized by the Slavers (a billion years ago).

1: I am not counting the “and then they rewrote the science texts on me” as that can happen to anyone and is pretty much unavoidable.

@james Davis Nicol:

While I agree with most of your criticisms regarding science and Jinx, I don’t agree regarding the possibility of stable planetary orbits in a binary star system. In his seminal work Habitable Planets for Man, Stephen Dole says there are orbital distances at which stable orbits are possible. It is unfortunate that such an old science book (2nd edition, 1970) is still the best reference on the subject.

I keep hoping Niven (or Niven & Lerner) will write a story explaining why Jinx has a shape which clearly cannot exist naturally. Obviously there’s something strange going on there, and it would appear the planet was moved from another star to its present location. We just don’t know who did it, or why.

http://www.rand.org/pubs/commercial_books/CB179-1/

There’s a free pdf of Habitable Planets for Man at the other end of the link but I wasn’t talking about binaries in general but the Sirius system in particular. A is much brighter than the Sun so for a planet to get about the same amount of energy from Sirius A, it would have to be about 4.6 AU. B is in an eccentric orbit, one that ranges as far from A as 8.1 and 31.5 AU. There could be times when B was only 3.5 AU from Jinx, where thanks to the inverse square law it would attract Jinx and its parent world almost as strongly as A does. It’s not a stable orbit for Jinx.

Much the same problem exists for Procyon: planets around Procyon A at the right distance to be habitable would be in the right neighborhood to be perturbed by Procyon B.

I forgot to mention: you could put habitable (well, pre-habitable; terraformable) worlds around both Sirius B and Procyon B. Both are fairly massive and very dim, so habitable planets would have to be very close to the white dwarfs, much closer than the approach to the more massive A stars. We know planets can form around post-stellar objects as well. They’d be challenging environments; tide locked and with orbital velocities around their white dwar primaries that would make impacts potentially very interesting (and make it expensive to get there and away). I’ve never seen anybody go for that option.

@james Davis Nicoll

Your claim that Sirius B’s eccentric orbit would bring it so close to the orbit of Binary (around which Jinx orbits as a moon) that it would disrupt the planet’s orbit, is thinking two-dimensionally and may be overly simplified. Consider how the orbits of Neptune and Pluto overlap. Yet, due to the 3:2 orbital resonance between Pluto and Neptune, and Pluto’s sharply inclined orbit, in three dimensions the two never get very near each other, so Neptune will never disrupt Pluto’s orbit. Perhaps a similar relationship exists between Sirius B and Binary.

* * * * *

Nereid, the moon of Neptune, is described in Ringworld chapter 4 as having flat icy plains. That sounds much more like Triton, which in our universe is Neptune’s largest moon. “Our” Nereid is quite small, irregularly shaped, and rocky. And in “The Coldest Place,” the first published Known Space story, Mercury is a one-face world; in our universe, it’s not. If planets and moons are different in the Known Space universe, perhaps some stars have different characteristics, too.

James,

… so for a planet to get about the same amount of energy from Sirius A, it would have to be about 4.6 AU

In principle, there’s a fair amount of freedom in terms of cranking down the greenhouse effect (remember that the surface temperature of the Earth would be about -18 C if we had the same albedo but no atmosphere) and/or increasing the planet’s albedo. Keeping the albedo the same, a planet at 3.5 AU from Sirius A would have a (non-greenhouse) temperature of 33 C; increasing the albedo to 0.6 drops the temperature to -7 C. Moreover, the shape of Jinx is such that the poles are in vacuum, and the human-settled regions are at high latitude, so that greenhouse effects there are reduced and the temperatures are lower.

I bring this up because calculations by Benest (1989, http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1989A%26A…223..361B) suggested that stable orbits could exist around Sirius A out to about 3.7 AU, with some isolated stable orbits as far out as 7.3 AU.[1]

Short answer: the three-body problem is complex. Having a habitable planet in orbit around Sirius A is (or was, by the standards of 1960s science) rather dicey, but not completely impossible. So I think that characterizing Niven’s astrophysics as “wildly wrong” is, in this case at least, a bit overstated.

[1] These are “stable” on timescales of a few hundred Sirius A/B orbits; more recent long-term stability analyses (not really possible in the 1980s) probably mean a smaller upper limit to stable orbits around Sirius A, but that’s getting into “and then they rewrote the science texts” territory.

Nereid, the moon of Neptune, is described in Ringworld chapter 4 as having flat icy plains. That sounds much more like Triton, which in our universe is Neptune’s largest moon. “Our” Nereid is quite small, irregularly shaped, and rocky. And in “The Coldest Place,” the first published Known Space story, Mercury is a one-face world; in our universe, it’s not. If planets and moons are different in the Known Space universe, perhaps some stars have different characteristics, too.

Nereid and the Mercury thing are examples of Science Marking On; the discovery about Mercury’s actual rotation came after “The Coldest Place” was sold but before it was published. Similarly, the first close look at Nereid was when, 1989? And not all that close and not repeated thus far so no doubt surprises are still in store.

I seem to recall Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven having an editorial comment from Niven to the effect that if Mars seems to change from story to story it is because Mars was actually changing from story to story as probes changed the models of Mars.

I bring this up because calculations by Benest (1989, http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1989A%26A…223..361B) suggested that stable orbits could exist around Sirius A out to about 3.7 AU, with some isolated stable orbits as far out as 7.3 AU.

Ah, but this only allows me to play the since we know Sirius B may have lost up to 80% of its mass during the transition from main sequence to post-stellar, we know that before Sirius B was a white dwarf, it and B orbited more closely card, which I

forgot to mention earliercunningly held in reserve.If Jinx and its primary were moved into the system later [1], that wouldn’t matter, obviously, but if they are native to the system, it does.

1: Presumably by the Outsiders. Speaking of the Outsiders, it seems to me that there’s only one species we see with the range to have taken hominids from Earth to the Pak homeworld [2] and that’s the Outsiders. I suspect them of also having created the Ringworld as an easily destroyed lab [3] for the study of their creations. I just don’t know why they might have wanted to make Pak.

2: Because we know and we knew in the 1960s that humans are too closely related to lineages established on Earth well before the Pak learned about Earth for us to have originated elsewhere.

3: Stars in our neighborhood tend to have velocities that differ from one another by 20 km/s or so. The Ringworld is about 200 ly from Sol; 20 km/s +/- would allow it to have been built in the same region of space as Sol at the time Homo habilis first appeared….

Pak protectors are warriors par excellence. They are also psychically “dead” and therefore immune to the Slavers’ Power. It seems quite plausible to suggest protectors are the result of a genegineered virus, because such a radical useful metamorposis caused by a virus appears extremely unlikely to happen by chance, and because natural selection would appear to select for a protector which is more willing to cooperate with others. So, if the tree-of-life virus was a genegineered to turn Pak into the ultimate warriors, is this an indication someone feared the Slavers still survive somewhere in the galaxy? Maybe a breeding population of Thrintun (Slavers) was put into stasis– or the Outsiders (or someone else) were afraid this happened, and wanted a population of warriors immune to the Slavers’ Power around just in case? Note this gives the Outsiders a motive to build the Ringworld and populate it with Pak, too.

Not that I’m arguing this is what happened, but it’s an interesting scenario.

There is a reason to preserve Bandersnach, although moving their entire world seems a bit excessive; they date back to the Slaver days and to the extent their verbal traditions preserve knowledge of that time (which admittedly after a billion years could be not at all) they are a unique resource.

On the other hand , maybe Outsiders just really like the Jinxian Bandersnach’s equivalent of Conway Twitty.

Even after 1.5 billion years, the Bandersnatchi on Jinx remember the Tnuctipun science language, and the treaty of something-or-other.

But I don’t know that their existance on Jinx is all that unique; according to Louis Wu, “There are bandersnatchi on a lot of worlds” (Ringworld, chapter 15). Jinx is just the first place that Humans found them.