I lost track of how many times I have seen Pan’s Labyrinth while using it as a case study for my Master’s thesis: I watched it at normal speed, on high speed, with commentary, and without; I watched all the DVD extras, then watched them again. After I had defended my thesis, my wife asked me what I wanted to watch. I replied, “One more time, all the way through.” Since then, I’ve viewed it in six different courses as my end-of-term movie (I realize students stop reading several weeks before the end of term, so I prefer to work with that problem, not against it). And when students ask me if I’m tired of watching it, I reply, “No. Every time I watch it, I see something new.”

I’ve met a number of people who cannot imagine someone subjecting themselves to an encore viewing, let alone so many they lose count. These viewers dislike Pan’s Labyrinth for its darkness, for the sorrow and tragedy of its ending. They find the brutality of Captain Vidal abhorrent (and well they should). Like Stephen King, they are terrified by the Pale Man. For many, the film’s darkness overshadows the light; consequently, viewers are often repulsed by it. I love Pan’s Labyrinth for its darkness, sorrow, and brutality. Without those harsh elements the film would be a milquetoast modern fairytale, as tame as The Lady in the Water: a tale of wide-eyed wonder without the wolf.

Fairy tales are often stripped of their darkest and most threatening elements, or transformed into complex morality tales to mirror current values, the victim of an overprotective industry of children’s literature. This is not a new development. To make fairy tales more suitable for young audiences, editors in Victorian England altered the tales, omitting events or elements they deemed too harsh. While many children’s fairy tale collections include a version of Little Red Riding Hood in which the huntsman comes to the rescue before the wolf attacks, the Brothers Grimm’s tale of Little Red Cap describes the “dear little girl whom everyone loved” being “gobbled up” quite suddenly. The wolf eventually meets his demise following an abrupt caesarean section rescue, compounded by a lethal case of massive gall stones courtesy of Little Red Cap, while in another version, Little Red Cap baits the wolf into drowning.

In some modern versions of Little Red Riding Hood, the wolf’s violent demise is replaced by a hasty getaway. Patricia Richards, in an article titled “Don’t Let a Good Scare Frighten You: Choosing and Using Quality Chillers to Promote Reading,” notes that the alteration of the wolf’s fate from execution to evasion is perceived as “less violent and less frightening, but children found it scarier because the threat of the wolf remains unresolved.” Rather than finding gory or horrific details of devoured heroes or drowned villains terrifying, children reported they found “stories with no endings as frightening.”

If ambiguity over the demise of the villain is maintained, then a sense of horror remains. This is a standard trope of the horror movie, utilized for the utilitarian possibility of the money-making sequel, but artistically for a sense of lingering dread. The audience feels a sense of relief when Rachel Keller, the heroine of The Ring seems to have assuaged the vengeance-driven ghost-child Samara; the major-key musical swell tells us they all lived happily-ever-after. This moment is shattered when Rachel returns home to tell her son Aidan all is well, only to have the hollow-eyed Aidan reply, “You weren’t supposed to help her. Don’t you understand, Rachel? She never sleeps.” The ensuing nightmare return of Samara onscreen has become an iconic moment in horror.

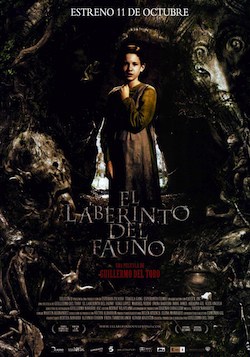

As a director, Guillermo Del Toro is well suited to dealing with horror in his fairy tale; his filmography prior to Pan’s Labyrinth, without exception, depicts a struggle between good and evil, from the subtle and nuanced Devil’s Backbone to the comic book morality of Hellboy, to the monstrous villains of Cronos, Blade II, and Mimic.

Captain Vidal, the wicked stepfather of Pan’s Labyrinth, serves both as the real-world, real-life villain within the film’s ontology of Franco’s Spain, and also the cipher by which the monstrosities of faerie can be understood. The two monsters of Pan’s Labyrinth, the Monstrous Toad and the Pale Man, can be read as expressions of Vidal’s monstrosity, viewed through the childsight lens of Faerie. Ofelia’s entrance into the colossal fig tree inhabited by the Monstrous Toad presents a subtle sexual imagery. The entrance to the tree is shaped like a vaginal opening with its curved branches resembling fallopian tubes, a resemblance which Del Toro himself points out in the DVD commentary. The tree’s sickened state mirrors her pregnant mother’s fragile condition, further manifested by a vision of blood-red tendrils creeping across the page of Ofelia’s magic book. This vision occurs immediately prior to Ofelia’s mother’s collapse due to a complication in the pregnancy, as copious amounts of blood run from between her legs.

The connection between the Tree and Ofelia’s mother is overt, and intentional, on Del Toro’s part. These images are symbolic markers for the sexual union between Ofelia’s mother and Vidal. Vidal is the giant toad, who has entered the tree out of lustful appetites, slowly killing the tree through its “insatiable appetite” for the pill bugs within. Vidal is a subtle Bluebeard—while he does not actively cannibalize Ofelia’s mother, his obsession with a male progeny is effectively her undoing. The tree was once a shelter for the magical creatures of the forest, as Ofelia’s mother once was shelter for her. Ofelia’s tasks can be seen both as trials to secure her return to her Faerie kingdom, as well as reflections of the harsh realities she experiences.

Captain Vidal is Del Toro’s gender reversal of the wicked step mother. Marina Warner notes that in many traditional fairy tales “the good mother dies at the beginning of the story” only to be “supplanted by a monster.” Here, the good father is dead, leaving the beast father to fill the void. From his first moment onscreen Vidal expresses an authoritarian patriarchal presence, exuding a classic machismo partnered with the harsh male violence expressed with multiple visual cues: his immaculate fascist military uniform and a damaged pocket watch, allegedly rescued from the field of battle where Vidal’s dying father smashed it, so his son would know the hour of his violent death in combat; Vidal tells his officers that to die in battle is the only real way for a man to die, as he storms confidently into a hail of rebel bullets. His blind confidence that his unborn child is a son bespeaks his utter patriarchy: when the local doctor asks how Vidal can be so certain that the unborn child is a boy, Vidal places a ban on further discussion or inquiry by replying, “Don’t fuck with me.” His obsession with producing a son is nearly thwarted by his own unrestrained violence when he kills the doctor for assisting a tortured prisoner to die, requiring a troop paramedic to preside over the delivery, ostensibly resulting in his wife’s death. This obsession with a male progeny is the true motivation for Vidal’s sexual union with Ofelia’s mother: his appetite is for food and consumption, rather than for sexual contact. Ofelia’s mother is simply another object to devour, like the Tree; once she is used as a vessel for Vidal’s son, she is no longer of use. When it becomes clear that the delivery has gone mortally wrong, Vidal urges the field medic overseeing the birth to save the child at the expense of the mother’s life.

The Pale man is another symbol of the consuming aspect of Vidal’s nature. This sick, albino creature presides over a rich, bountiful feast, but eats only the blood of innocents. Del Toro’s commentary reveals that the geometry of the Pale Man’s dining room is the same as Vidal’s: a long rectangle with a chimney at the back and the monster at the head of the table. Like the Pale Man, Vidal also dines on the blood of innocents. He cuts the people’s rations, supposedly to hurt the rebels, but eats very well himself; in many scenes he savors his hoarded tobacco with almost sexual ecstasy; but this is not a man with sexual appetites. It is true that he has copulated with Ofelia’s mother, but he is more akin to the Grimm Brothers’ Big Bad Wolf, who wishes to eat Little Red Riding Hood, than the wolf of “The Story of Grandmother” who invites the girl to strip before coming to his bed. Vidal is the sort of wolf James McGlathery describes, one who is neither “a prospective suitor, nor even clearly a seducer of maidens as one usually thinks of the matter. His lust for Red Riding Hood’s body is portrayed as gluttony, pure and simple.” The conflation of consumption, of food, tobacco, and drink, as Vidal’s passion throughout the film underscores this idea. This gluttonous obsession proves Vidal’s undoing: in a wonderful use of foreshadowing, Ofelia kills the Monstrous Toad by tricking it into eating magic, disguising them as the pill bugs the monster lives on. This mirrors the end of the film, when Ofelia renders Captain Vidal nearly unconscious by lacing his liquor glass with her deceased mother’s medication, tricking him into drinking it.

These monsters are clearly Vidal’s avatars in Faerie. All of the monsters in Pan’s Labyrinth are blatantly evil, without remorse for their actions. All act from unrestrained appetite: the frog devouring the tree, the Pale Man dining upon the blood of innocents (his skin hangs in flaps, implying that he had once been much larger), and Vidal sucking the vitality out of the people around him. The first two are monstrous in their physical aspect; the Pale Man is especially frightening as he pursues Ofelia down his subterranean corridors, hand stretched in longing, pierced with ocular stigmata, “the better to see you with.” Vidal by comparison is handsome and well-manicured, meticulously grooming himself each morning, never appearing in the presence of his subjects as anything less than the perfectly arrayed military man. His monstrosity is internal, although Mercedes’ mutilation of his face renders it more external for the film’s climactic scenes. An attentive viewer will also note further foreshadowing in the similarity of the Pale Man’s staggering gait and outstretched hand, and Vidal’s drugged pursuit of Ofelia with arm outstretched to aim his pistol.

Vidal’s external brutality proves to be the most horrific in the film, eclipsing any terror either the Monstrous Toad or Pale Man could conjure. Friends avoided seeing the movie based only on descriptions of Vidal bashing in a peasant’s face with a bottle, or performing torture on a captured rebel, (This second atrocity is performed offscreen; the audience only sees the result of Vidal’s labors). “You can either make it spectacle or dramatic,” says Del Toro in the director’s commentary. In film, a cut on the cheek or on the temple has become commonplace enough that it doesn’t even register for the average filmgoer. The mutilation of Vidal’s face by Mercedes, the rebel-sympathizing housekeeper and surrogate caretaker of Ofelia, is the sort of violence that “immediately elicits a reaction.” Del Toro deliberately designed the hyperbolic violence of Pan’s Labyrinth to be “off-putting, rather than spectacular … very harrowing … designed to have an emotional impact.” The only time Del Toro utilizes violence for spectacle is in the scene where the Captain sews his mutilated cheek back together. The camera never turns away from the spectacle of the Captain driving in the needle and pulling it through, over and over, to illustrate how relentless a monster Vidal is: like the Big Bad Wolf (or the Terminator) he will not stop until he is killed.

If the Big Bad Wolf must die to make the horror a fairy tale, so too must Captain Vidal. While the Captain is an imposing onscreen threat, there is no question as to the ultimate outcome. The villain cannot simply die, for the violence must be hyperbolic: the monstrous toad explodes; the Pale Man is left to starve in his lair. Mercedes’ reply to Vidal’s request that his son be told the time and place of his death is, “He will never even know your name.” At the end, the Captain is not merely killed; he is obliterated. Vidal and his avatars receive their “just reward,” as dictated by the tradition of the fairy tale.

To have toned down Vidal and his monstrous twins would be to tone down the layers of menace. Real or imagined, Ofelia’s actions would lose their significance: her rebellious spirit would be nothing more than adolescent acting-out, a temper tantrum rendered fantastic. However, it is the double-resistance of both Ofelia and the rebels in the hills that provide the thematic thrust of Pan’s Labyrinth, the resistance of Fascism in all its forms. Discussion of this film often centers on whether or not Ofelia’s quests into the realm of Faerie are real. Those who conclude she has imagined them conclude her victory is an empty, illusory one.

This misses the point entirely.

Real or imagined, Vidal and his avatars are symbols of Fascism, of unrestrained oppression. Ofelia and the rebels in the hills exist to resist. In the smallest action of refusing to call Vidal her father, to the life-risking act of kidnapping her infant brother, Ofelia displays a refusal to be cowed in the face of monstrous evil. This is what Del Toro is concerned with, and it is why his villains are so monstrous. In the world of Pan’s Labyrinth, disobedience is a virtue: when Vidal learns of the Doctor’s betrayal, he is confounded, unable to understand the Doctor’s action. After all, he is the monstrous Vidal. The Doctor knows this man’s reputation—he must realize the consequence of his action. And yet, he calmly replies, “But Captain, to obey – just like that – for obedience’s sake… without questioning… That’s something only people like you do.” And to disobey, to resist the monster, is something only people like Ofelia, Mercedes, and the rebels do. To have them defy anything but a true monster would cheapen their resistance. And this is why, despite the difficulty in witnessing the darkness, the sorrow, and the brutality of Pan’s Labyrinth, I would never trade the Big Bad Wolf of Captain Vidal for the toothless lawn-dogs of Lady in the Water.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.

Thanks for the article, I’ve found it really enlightening.

I’m also unable to re-watch the film, but not because of all the violence, but because of Ofelia. The little girl’s death was so painful and tragical that I tear up just thinking about it. I don’t think I could re-live it again!

Great read. I love this film, and for many of the reasons you listed above. I was a little afraid to read this, honestly, because so many people seem to misunderstand. I love the darkness, the tragedy, of this film, and it just wouldn’t work without it. Thanks – now I have something to point people who don’t get it at. :P

I actually expected it to be more of a horror movie, when I saw it. The ending, while being consistant in the story, seemed a bit too… Happy, I guess.

Thanks so much for the excellent analysis, Mike! I remember seeing Pan’s Labyrinth for the first time, all by myself in a small theater downtown, and having to remind myself to breathe, and to blink, at points in the movie–it was so beautiful and so very disturbing. I’ve seen it several times since then, and I totally agree: it’s a different experience every time. And the Pale Man is still the most terrifying character I’ve ever encountered in my adult movie-going career–but I’m not complaining :) It’s just a brilliant film…

I have watched this film recently and I loved it! I wept like a baby, but I will certainly watch it again.

And I am glad that the film is so uncompromising re: darkness – it was a dark, dark time in European history.

Mercedes’s survival and the fleeting victory of the freedom fighters felt all the more uplifting and unexpected, since they happened against the gritty realistic background rather than Hollywoodesque atmosphere of “guaranteed happy end”.

Vidal may seem like a perfect monster, but in fact there were a lot of people just like him in positions of power at the time.

What sincerely surprised me was that Del Toro and the team saw the doctor as a coward. He didn’t come over to me that way at all.

As to the fantastic part – well, IMHO it is supposed to remain an open question how “real” it was supposed to be. In any case, it gave Ophelia strength to resist soul-crushing circumstances surrounding her. Even though it was also horrible, it empowered her and gave her hope. Which is more than millions of kids who have died by violence in that period had.

@3. Hmm… I always saw the ending as soul-crushingly sad.

As was pointed out in the article, the fantastic parts of the movie are direct parallels to other things going on, and I always saw them as being the deranged musings of a deeply troubled, and forlorn, child in war time. And at the ending, she doesn’t actually die until AFTER the scene with the faun, if I recall.

Jexral @6:

Ophelia did somehow escape a locked room and sneaked into Vidal’s. Mercedes subsequently saw a drawn outline of a door in it, too. So, I’d say that it is an open question whether the fantastic part was pure fantasy. But even if it was, I wouldn’t call it “deranged”, as it gave Ophelia strength and hope.

One of the greatest films of the decade, if not the last quarter century. And I can barely stand to watch it.

The ending of this film made me feel like I’d been kicked in the stomach. I managed not to cry in the theater, and kept it together when I watched the DVD with my parents. I’m not sure if I could take it again.

I took the vision of the throne room as Ophelia’s dying fantasy. Those in the audiance who can suspend disbelief might believe in it along with her. I won’t try to talk them out of it . . . any more than I would have tried to talk Ophelia out of facing facts as she died. You need some wonder and fantasy to deal with hard times.

Del Toro was associated (producer?) with the powerful psychodrama / thriller The Orphanage, which has a similar ending. Utter tragedy softened by a wistful fantasy of happiness and closure. That made it all the more poignant.

Thanks for the amazing analysis! I love this movie. I have to say that I’ve always considered the fantasy aspects “real” in the context of the movie. As mentioned above, her escape into Vidal’s room validates it for me. So the ending isn’t quite as sad for me as others who lean toward the opposite view.

I don’t have enough Spanish to know whether it really is, but “Vidal” reads to me like a cognate of vital, which sheds some interesting light on the ideas explored here. The Captain isn’t a source of destruction here because he’s an embodiment of Death, but of Life – the kind that’s “red in tooth and claw,” unrestrained and unchecked, the state of nature run amok. He consumes and reproduces with such enthusiasm because he intends to be the most alive thing in his realm, and to propagate in his own image; his Faerie avatars are a child-devourer and a parasite (feeding on a womb, no less), both representing survival-of-the-fittest strategies with many parallels in the natural world.

This suggests a reading of the film that presents fascism as an invasive species (which lends some extra resonance to the fact that one of Vidal’s monstrous shadows is a toad). It’s far from the first time Del Toro has visited this theme; Mimic, Blade II, and Hellboy all deal at least in part with struggles against invasive predators with no natural enemies. So the Captain’s fate isn’t only fairy-tale justice, it’s also the only possible solution to such a threat: total eradication.

I think there’s something here, too, connecting to why Del Toro might see the doctor as cowardly. In many of his other films, it’s a marriage of mysticism and reason that provides the key to overcoming the invading menace (thus the signature “autopsy of something horrible” scene that often provides his heroes with the knowledge necessary to find the weaknesses of their adversaries). Here we have mysticism without the balance of reason, and it’s not sufficient. The one man of science who could take the monster apart enough to understand how to defeat it does too little, and the result is tragedy.

(All of which should make us all a little sadder that we’re not going to see his At the Mountains of Madness anytime soon – a story that seems ready-made for his themes and obsessions. A shoggoth, after all, is pretty much a scaled-up cane toad, with pseudopods.)

Maestro – fantastic thoughts! I agree with your reading of Vidal/Facism/Fecund Evil. And it does make for a great connection to his greater filmography. Someone needs to snap that puppy up for a graduate project.

I too, am saddened we’re not going to be seeing At the Mountains of Madness by Del Toro’s hand in the near future. It would have been brilliant, I’m sure.

Thanks for the kind words, Mike! (And also for the word fecund, which I realized was the term I was reaching for amid that flailing around up there.)

I’m almost certainly not the guy suited to tackle it, but I agree that there’s at least a Vry Srs essay’s worth of material to be mined in “Guillermo Del Toro and the Ambiguous Portrayal of Nature” or summat like that. (There’s certainly a lot to chew on there when he returns to Faerie for Hellboy II, frex.)

Graditude to the writer.

I watched this film in the theatre in 07. I must have been mulling it over in my subconscious since. Recently I have decided to watch it again, and while I wait for it to arrive I have been reading what I can find online about it. I have been quite disappointed with most of what I read. This piece is excellent.

I like what you say about the darkness. In fact, the hope provided by the Faun is quite dark in comparison to the Christian promise of heaven. Vidal seems like the kind of force behind the Christian world anyway. Perhaps the tale, by not including Christianity brings it’s beatiful contrasts to a less contested point. The darkness then of the Faun is much preferable to that of the other. The Faun requires a lot and simply does not give the answers. Ofelia is not rescued by him, but challenged to discover the strength of her own destiny. Her refusal to find passage into a safer world through the blood of an innocent seems like a metaphorical refusal of refuge in the sacrifice of the innocent blood of Christ.

To me Ofelias fate was magnificent, so pleasing. She finds her path to the other world in her own character, her own irrepressible truth. She is important in the other world, lives long, but is not eternal. This can be a challenge to the desirability of the notion of eternal life.

I enjoyed the historical backdrop, but didn’t focus on the meaning there. The poorer the people were, the more connected to the old ways, the earth itself. People are being taken from more natural alignment and being enslaved in industry, anyone standing in the way tortured and killed.

These messages were the subtle depth few referenced. The heart of the rebel is more aligned with the Faun. I read a bit about Del Toro’s notebook in which he takes no credit for the layers of meaning leaving me to wonder if he himself was unaware of them. Quite possible, I thought, and perhaps though, given the outrage I saw on so many comments online, he was sidestepping the controversy. It is a masterpiece that connects the basic good in a person, allowing them to sidestep all the usual indoctrinations for a moment and return to the indigenous soul and the still true world of magic and destiny. In that moment we will connect with the horror of the places we have accepted that we cannot have free will, where we have been overpowered by the authoritarians of or lives. How able to flow is Ofelia in her nature? Her mystic nature draws the resources she needs to bring healing and compassion where they lack, accept loss and death, to follow her heart. No wonder the faeries revealed themselves to her.

People writing about this film want to figure out whether or not the magic world was real. Del Toro presented it as her own imagination in what I read. I would flip it around, wasn’t it the others who were seeing the false reality because they could not dare to see below the surfaces? Unwilling or unableto see into the true nature of reality. Perhaps, if they were slightly more willing to stare death in the face.

Anyway, thanks for your deep appreciation for the significance of this work. I needed to connect with someone who was feeling it. I recommend the Mayan Folk tale presented by Martin Prectel, The Disobediance of the Daughter of the Sun.

All bless.

Fantastic analysis. Have you also considered that Pan’s Labyrinth deals with themes concerning the death of innocence (childhood) and the horrors associated with it (especially for women). Magic and faeries are replaced by sobering realities (brutality, sexuality, etc.). The use of a labyrinth as a symbol is especially poignant in this regard. Cheers.

This is an absolutely terrific review of one of my most loved movies. I’m grateful. Thank you! By the way, Ofelia’s death IS gut wrenching, but I am one of those who take comfort in her “fantasies”. People, Frodo Lives!

Wonderful. I feel the need to share this to my network. I hope you don’t mind.

I just love that the faun’s tests on behalf of Ofelia’s father (making sure she’s not “mortal” and still pure of heart) are a direct analogy to making sure she hasn’t adopted to capitalist ideology. As Bukowski said, “The problem was you had to keep choosing between one evil or another, and no matter what you chose, they sliced a little bit more off you, until there was nothing left. At the age of 25 most people were finished. A whole god-damned nation of assholes driving automobiles, eating, having babies, doing everything in the worst way possible, like voting for the presidential candidates who reminded them most of themselves. I had no interests. I had no interest in anything. I had no idea how I was going to escape. At least the others had some taste for life. They seemed to understand something that I didn’t understand. Maybe I was lacking. It was possible. I often felt inferior. I just wanted to get away from them. But there was no place to go.” Her imagination represents what has been labeled “Utopian” by critics of socialism/anarchism, whose movements were most potently expressed in the Spanish civil war (not to mention suppresed by Franco and the rest of the “mortals”

I can’t give you a great analysis of Pans Labyrinth but I can tell you I went through more emotions than I knew I had watching it. The innocent child taken into a world that would ultimately seal hers and her mother’s fait and still the film seems so beautiful and so dark surrounded by nature and fantasy figures. I felt compelled to watch and completely forgot I was reading sub titles. The Faun I thought was a touch eerie and almost sinister himself, did anyone else think this?

either way I cry my eyes out whenever I watch this film and reading your comments make me want to watch it again.

Very nice thoughts. I couldnt watch all the scenes as most of the time i had my eyes covered, but love it and would definetly watch it again. While i was watching it i was expecting that Ophelia would have been sexual harrest by Vidal. Any thoughts on that?

This is a really great analysis… I never understood the meaning behind the Pale man and it gave me a more in depth understanding of the movie… the ideas i saw in the move are nowhere as detailed as this.. I now know what to write for my spanish essay on this film

The Pale Man sees through it’s eyes because Vidal only believes in what is tanginible, unlike Ofelia, who believes in fairy tales

I prefer to believe that the Fairies and the Underworld were constructs of Ofelias’ mind, to help her deal with the unbearable situation she had been dropped in.

Ofelia, used the imaginary faries, labrynth, Faun etc as an escape, she was alone on that farm, and this was her escape mechanism.

In the end, Ofelia used this construct to deal with her own death, preferring to think that she was simply moving to a better place, rather than dealing with death it’self (something many religions encourage)

Overall a great film, something teens and adults can watch, and take different meanings from. A sad ending, yet a good ending. Have watched it twice now and can’t believe how good it is.

Thank you so much for this excellent t analysis, especially of the Toad and Pale Man as they correspond to Vidal. I’m wondering if you could please share your thoughts in who or what the Pale Man is, in his own particular world. If we were to extract the Pale Man from being a symbol for Vidal and try to understand what he is in the underworld and only in the underworld, what could we surmise as to his origin and nature?

Thanks,

Chris

The Pale Man ate two fairies because Ofelia ate from the table.

Vidal caused the death of the tortured stutterer, and the doctors, because the rebels stole from the locked hoard.

carmen’s condition improves when ofelia puts the mandrake root under the bed, and she goes into labor and dies when it’s thrown in the fire. ofelia exits the locked room and the chalk shows up on vidal’s desk/table in the real world. the fig tree that had been drained of life by the toad is blooming again before the fade to black.

the baby brother ofelia protects (the scenes of her talking to him in the womb just knock me out) ends up in the arms of the most heroic figure in ofelia’s real life–who has herself fairly miraculously survived.

it’s a grim film about a grim time, but the ending (and the message–“exist to resist” sounds about right) is pretty damned hopeful.

Beautifully written. Very Enlightening. You’ve helped me to better understand Pan’s Labyrinth. It’s a poignant, tragic movie, but worth watching. I don’t believe Ofelia was imagining the fairies or the Faun. In an interview, Del Toro said it was real. Every bit of it. The fantasy world and reality often coexist alongside each other. Think about it. Also, it’d be nice if you discussed the use of color in the film.

At the end of the first scene,after she has seen the faerie,Ofelia walks back to the car,her back to the camera,and the faerie comes up in the deep foreground of the same shot.Since only the audience sees this happen,not Ofelia,it is a kind of Shakespearean moment in which the existence of the faerie is meant to be real,not something that only Ofelia believes delusionally,or in fantasy.Del Toro is showing us the reality of their existence,ab initio.We are shown that they are real,and we are meant to believe it.In that moment,the reality of our world, as well as Ofelia’s,merges into the same vision.The rest of the film flows from that point. If the faeries are real,it must follow that so is the Pale Man,the Faun and the Toad–as much as Vidal,as much as Mercedes.As the film opens,we are meant to be reborn as children,and to see the world in the simple moral terms of Good and Evil.There is not much gray here.In essence,something is good or something is evil. Ofelia is not merely returning to the car;she is leading us,and we must follow her. The film contains countless visual and thematic subtleties that become apparent only after multiple viewings.If there are complexities,they are facets of the same diamond,flawlessly cut by Del Toro,and they arise from simple,basic themes.

To Mr. Del Toro and to Mr. Perschon,l would say: Bravo!

Lots of thanks to the writer. I’m presently studying Pan’s Labyrinth for my AS Spanish exam, which is tomorrow and I loved the film and all of the hidden messages within it that i noticed more and more each time I watched it through. Today was the last time I have to watch it for my course, but certainly won’t be the last time I watch it as, like you put it, the more I watch it, the more I notice bits of it. You put down a few ideas that I hadn’t come up with, so reading this really helped me collect together my thoughts a lot more for the exam tomorrow.

Best wishes and here’s hoping my exam goes okay!

Austen

Just stopped by to see if there were more comments since the last time I was here, and wow! People are still reading this article, which is a real gift. Thank you all for your lovely responses and further insight. This is what a comment thread should be.

Polyxeni Ath asked if I thought Vidal had sexually abused Ofelia – I have never seen anything in the film that leads me to believe that happens. Vidal’s appetites are not sexual. He does not threaten to rape Mercedes, for example. This only reason he likely had sex with Carmen was to produce a son. So I don’t think his abuse of Ofelia is coded at all sexually, not even at a nuanced or subtle level.

To Chris Van Allsburg…my God, are you THE Chris Van Allsburg of Polar Express fame? If so, thank you for your book. We love listening to Liam Neeson read it, though we heard you for the first time last year on a Polar Express train experience.

ANYHOW, to address your question about the Pale Man – Understanding his place in the underworld…he’s an ogre, a man-eater, the archetypal cannibal represented by Grendel and Dracula. He’s any monster who promises “I’m going to eat you up!” But he only subsists on human flesh, particularly that of the innocent, if the pile of empty children’s shoes are any indication. Given that, in the end, he’s likely one more mask for the Faun, who seems to have been the maestro behind Ophelia’s ordeal, it’s difficult to isolate him from his relationship to Vidal and the Faun. From a secondary world perspective, what’s he doing down there? Who feeds him children? So it’s a problematic question, but I’m thankful for the challenge it’s presented me.

Speaking transculturally,in terms of the Pale Man as Devourer,in lcelandic mythology,there is the terrifying Gryla (gree-la).She is a troll giantess with an insatiable appetite for her favorite meal,a stew,made from naughty children.She descends among them at Christmas time to find the bad ones,and spirit them away to her frightening kitchen.At the same time,as each of the Twelve Days of Christmas arrive,she unleashes her thirteen nasty children,one daily,on the population,but they commit only minor crimes,more annoying than evil–slamming doors all night,licking the spoon in a bowl,stealing sausages from the smokehouse etc.However,if a naughty child,caught in her huge clutches truly repents sincerely for what he or she has done,Gryla is rendered powerless to harm them,and the child is returned to it’s home.She always knows if the child is lying only to save itself,so insincerity or lying spells doom.The legend is somewhat different than many,in that there is a way out for the contrite.Ofelia didn’t have that option as she fled the horrific Pale Man,cruel devourer of the faerie.

Referring to your earlier point that there is a modern tendency to downplay violence in children’s literature,a trend l deplore because it reduces resistance to so much fluff,the Gryla legend remains terrifying,but allows redemption for the righteous if they are brave and true and good enough to learn their lesson and stare her down.True goodness can always triumph over pure evil.

Hypercreative… or grandiose?

Some thoughts on the names in the movie:

Vidal: His name means “life.” Ironically, this is a negative. He is the devouring aspect of life, consuming and destroying. He is sure that controlling access to food, the stuff of life, will force the people to capitulate. Even his quest to produce life (a son) is destructive, leading to the death of his wife.

Carmen: Latin for song, but Ofelia’s mother doesn’t sing for her during the film.

Mercedes: Her name means mercies and is associated with the Virgin Mary. Mercedes shows mercy and compassion for Ofelia as well as other characters. Although being a member of the resistance is not normally associates with mercy, Mercedes gives food to the hungry and protects them from discovery. However, although she acts as a mother figure to Ofelia, it may be significant that she cannot remember the words of the lullaby to sing to Ofelia. If Ofelia’s mother is “song,” Mercedes is not truly able to take her place.

Pedro: His name means “stone,” which may suggest strength and commitment to his goal as well as his area of strength being in the wilderness or stony mountains. It is also a form of Peter, which may be to associate Pedro with St. Peter, considered by Catholics to be the first Pope, contrasting him with the corrupt clergy sharing dinner with Vidal. However, Pedro also sounds like “perdido,” meaning lost. The resistance may win in the film–and they may survive by escaping to France or elsewhere–but they will ultimately lose the war.

Pedro and Mercedes are also (as far as I remember) the only characters with clearly religious names, names associating both of them with two of the most important Catholic saints. This is important because, while Ofelia is aided by creatures out of myth and Vidal is supported by corrupt clergy, Pedro and Mercedes may be bound to what we think of as the “real world” but they are not forces in opposition to Ofelia.

Dr. Ferreira: His name means “smith” or “iron-worker.” The doctor’s character is strong as iron. He does not bend or yield to Vidal’s/life’s demands, remaining true to what he believes is right. Also, while Ferreira is a real last name, there are other variations, such as Ferreiro, that have what a Spanish speaker would recognize as a masculine ending. Ferreira has a feminine ending. Vidal is misogynistic and does not recognize the kind of power the doctor has–healing, inner strength, compassion, virtues that are often considered softer or feminine. Vidal is the last person who can understand iron cast as feminine strengths.

Ofelia: Here, things get interesting. The other names would be fairly clear to a Spanish speaker, coming from closely related romance languages. Ofelia, however, comes from Greek, a very different language. It means “helper,” which seems obvious enough. Ofelia is the one given tasks and a quest. She also tries to help and protect her mother, brother, and Mercedes.

However, while I don’t know if this goes for people in Spain, most English speakers hear the name “Ofelia” or “Ophelia” and think “poor, doomed girl who dies before the end of the play.” Ofelia may or may not be mad or hallucinating in the film. Like Ophelia, she ultimately speaks freely to the murderer in power. Both of them have deaths that have fairy tale qualities. Ophelia is described as “mermaid-like,” a creature of the other world, and sings “snatches of old tunes.”

So, as the character allied with fairy tales and myths, Ofelia has a name befitting a character from an old tale, a name that says she belongs to the Underworld or death.

But, that’s not the only name Ofelia has. The faun says she is really Princess Moanna. Now, this was before there was a Disney princess with that name. While the name does have a meaning in Hawaiian (or it does according to a quick, online search which I’m sure is accurate), “ocean,” I’m assuming Del Toro wasn’t thinking of that and that it’s significant Ofelia’s other name has no clear meaning. While the other characters have very clear, easy to understand names (and ones that may be a bit to on the nose) “Ofelia” is a less clear name, open to interpretation, and “Moanna” has no clear meaning at all.

Vidal, whose name means life, is a negative character (and represents that negative aspects of life and survival). Ofelia, who is associated with death, is a positive character. For several characters, death is a victory. The captured fighter chooses death rather than torture and the risk of betraying his comrades. The doctor chooses death over serving the corrupt Vidal, a choice Vidal cannot comprehend.

For the the Vidal, death is a tool of power and punishment. He kills those who oppose him and assumes the desire to live is so strong being able to kill or to preserve life by controlling people’s access to food will ultimately give him power. Seeing his son as only an extension of himself, he does not fear death if his son lives but is horrified when he’s told his son will not know about him or even know his name. His bid for immortality has failed, cut off by a woman named Mercies who he had assumed was powerless.

By the way, on another possible symbolism level, christenings are when a child is traditionally given a name. It is also when a child, through baptism, is cleansed of the sins handed down from parent to child. Mercedes, associated with the Virgin Mary, has just decreed that this child will be free of both his father’s name and the gruesome inheritance that goes with it.

The faun: You would think, of course, that the faun is Pan. However, the name “Pan” means all (which was considered quite appropriate for a god of nature and wild places, basically everything that existed outside the small, protected spaces of ancient towns and city states). He himself says he has had many names and that many of them are forgotten.

So, the “real world” is dominated by names with clear, specific meanings. Ofelia’s world, whether it is a world of her imagination or a reality the other characters are unable to recognize, is one where names are ambiguous and, in the faun’s case, perhaps even meaningless. This seems to be an inversion of what we would usually expect. Vidal’s “reality” is ultimately the world that relies on simplicity. It cannot understand complexities, like a doctor who is willing to die or that a child could have reasons for trying to escape him that don’t have anything to do with sides in a war.

Ofelia’s world, on the other hand, is one of complexity. It has room for forgiveness as well as cruelty. It defies simple solutions and meanings.