Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the fourth installment.

Alan Moore and his collaborators may have stumbled a bit in the middle of Book Two of the Marvelman saga—with its abrupt departure from Warrior, its conventional revenge narrative, its reliance on a young artist who was not capable of delivering the subtlety or the power the story needed—but artist Rick Veitch helped to conclude the second act of Moore’s run on the character with a kind of visceral flair, and now we get to the end: the six issues of Miracleman that form “Olympus.”

“Olympus,” distinctly envisioned as Act III of Moore’s Marvelman opus (and if “opus” seems too grand a word for superhero comic books, then you probably haven’t yet read the operatic chapters I’m discussing this week), is the most complete and masterfully-structured of the entire Marvelman run. Moore began his work on the character by exploring the notion of “What if this superhero stuff were set in the real world?” turning a cornball cast into something far darker, and more tragic, and more human. In “Olympus,” he takes the story to its logical conclusion: “If superhumans really existed, they would be like gods. What would the existence of actual gods on Earth do to the world?”

Moore takes the idea of “costumed superheroes as the new mythology” and literalizes it, but not in the way readers at the time might have expected.

And, yes, I’m still calling the protagonist “Marvelman,” though as we reach the end, and the Warrior days drift farther and farther into the past, it’s getting harder to pull off such a conceit.

Miracleman #11 (Eclipse Comics, 1987)

Two items of note, before we proceed: (1) Alan Moore clearly identifies this final art as “Book III” right on the title page of this issue, and each issue has a mythological title. This one, for example, is “Cronus,” a reference to the Titan of time, the father of Zeus and his siblings. I’ll talk about him in a minute. (2) John Totleben, Swamp Thing inker, and later penciler and cover painter, joins Moore for the last six issues of Moore’s run. Though he gets some help from his friend Tom Yeates on the final issue, he basically pencils and inks the whole of Book III, and his graceful yet harrowing linework perfect for the tone of “Olympus.” This final arc would feel far less complete, and far less masterful, without his presence as the artist.

If Marvel ever does reprint any of this stuff, which I’m beginning to doubt, and they do bring in some artists to redraw or touch up any of the previous issues, which I doubt even more, then they can certainly feel free to leave all of these Totleben pages alone. I insist upon it, in this fantasy declaration of something that will never happen anyway.

Back to “Cronus.”

So the story of the mythological Cronus goes like this: the Titan believed that one of his children would overthrow him (that was always the prophecy back in those days anyway) and to prevent such a thing, he swallowed each of his babies as they were born. Goya painted a picture about it. Rhea, his wife, took the last baby and hid it away, giving Cronus a rock in swaddling clothes to eat instead. Long story short: that rescued baby turned out to be Zeus, who grew up, slew his father, freed his brothers and sisters from his dad’s belly, and the gods became the gods and ruled over everything.

So who is the “Cronus” of the title here? Is it Marvelman himself, the first superhero, who tells the story of Book III from the future? (The distant future, of, gasp, 1987—because, remember, the timeline of the Marvelman stories is still stuck a few years before this issues was published, due to the story’s post-Warrior delay and the step-by-step narrative of Books I and II which took place almost in “real time.”) Is it the Qys, or the two representatives of that shape-changing alien race who were responsible for kicking off the whole Marvelman plot when one of their ships crashed to earth years ago?

Well, it’s the latter, because they were the first, and they started it all (plot-wise). Moore lets us know, when Marvelman actually refers to the Qys as “Titans” in the text of the issue.

But yet there’s something not quite accurate about Marvelman’s position in this new pantheon as the Zeus figure. He’s a Cronus kind of character too, in the way that he holds on to his status and, with loneliness, recollects a world in which he has destroyed that which has tried to overthrow him.

It’s not as simple as the Qys-as-Cronus-analogues. Moore provides more subtle layering than that, and this is no myth about the supremacy of the gods. It’s more about the inhumanity of the gods, and the humans who cannot grasp the implication of the divine.

Like poor Liz Moran, mother of Marvelman’s daughter, wife of the man who would be Marvelman. She’s out of her league when one of the Qys come for her—or the baby—in the form of a Lovecraftian, fish-headed monstrosity. Miraclewoman saves her, tearing out the creature’s throat so that it cannot say its magic word of transformation. She appears with radiant beauty, her hands dripping with blood. “Aphrodite,” reads the caption, “risen from the churning foam where fell the manhood of Cronus.”

Miracleman #12 (Eclipse Comics, 1987)

In this issue, not surprisingly titled “Aprohrodite,” we learn the Miraclewoman backstory.

Her story parallels that of Mike Moran. She, too, was experimented upon. She, too, was sent to infraspace, genetically altered with Qys biotechnology, thanks to the devious hands of Dr. Emil Gargunza. But what makes her tale even more chilling is that she was not part of the Marvelman government conspiracy, the Zarathustra Project. She was a private experiment. A side project for Gargunza. And he sexually abused her.

This is where we get into a troubling concern for any sustained Alan Moore reread. I know what’s coming, and I know that this is just the first case of rape or sexual assault we’ll see in Moore’s work. I’m not particularly interested in tracking the “rape motif” in Moore’s work, but it’s also going to be impossible to ignore. Because, as in the case of this issue, with Miraclewoman, Moore doesn’t use the event meaninglessly. Here, it is seemingly meant to have devastating power. To show the physical corruption of an innocent soul, and to show the contrast between the sordid flesh and the purity of the imaginative world where young Miraclegirl would fly free and have adventures.

It’s also no coincidence that the panels showing her imagined superhero adventures recall the Golden Age superheroics of bondage characters like Wonder Woman or Phantom Lady. Moore’s Miraclewoman background tale provides commentary upon the history of the subjugation of female heroes in comics, and makes that sexual subtext part of the text of this story.

Then the alien Warpsmiths arrive, regal and powerful and ominous, and teleport Marvelman and Miraclewoman into space, where they will discuss what everything means, and what’s next, leaving Liz Moran and baby Winter behind.

Meanwhile Johnny Bates is beaten in a public restroom, and Kid Marvelman presses to escape his prison of the mind.

Miracleman #13 (Eclipse Comics, 1987)

All of these “Olympus” issues (at least the ones so far) begin and end with the framing story of Marvelman at world’s end, flying around inside a beyond-glorious futuristic palace. The price of godhood, it seems, is isolation. There’s beauty on this new Mount Olympus, but sadness as well. And this story opens with a grave, and an artifact: the helmet of Aza Chorn, Warpsmith. The “Hermes” of the title of this issue.

But there’s no indication of danger to Aza Chorn in this issue, not once we see what’s actually unfolding here. It’s mostly exposition—though Moore is quite good at making it sound interesting and vital—about the relationship between the Qys and the Warpsmiths, and the fate of Earth.

In a nutshell: the shape-shifting Qys and the super-swift Warpsmiths—aliens, or space gods—now had to reckon with Earth. It was an “Intelligent-class” world now, with the birth of Winter Moran. She, not Marvelman, nor Miraclewoman, was the true spark of something new. And a Qys/Warpsmith summit is held/was held (time is ever-shifting in Moore’s Marvelman saga, but not in a confusing way), to determine next steps. Violence between the two cultures, with the winner taking charge of Earth, was a predictable outcome, but Moore ignores that cliché—and allows the Qys to dismiss it on the page—in favor of a truce, where Earth would be observed, and emissaries from both cultures would stand watch.

Marvelman and Miraclewoman would represent the Qys, and Aza Chorn, Warpsmith warrior, and Phon Mooda, his female counterpart, would monitor the planet for the Warpsmiths.

The Pantheon is nearly fully formed, as the gods return to Earth.

Liz Moran leaves Marvelman and her child. “I’m just human,” she says. “And you’re not.”

Miracleman #14 (Eclipse Comics, 1988)

This issue may begin with Marvelman dancing alone, but it’s actually the launch of the official “Pantheon” (as in, that’s the title, finally)!

We have our Zeus in Marvelman, our Aphrodite in Miraclewoman. You’ll note a distinct lack of a balancing Hera figure in this mythos, for whatever it’s worth, unless you count Liz Moran, who had left the superhumans behind. Our Hermes in Aza Chorn, and, presumably, our Athena in Phon Mooda. Now we meet Huey Moon, the homeless pyrokinetic, as their Apollo.

By this point, Moore has broken his own rule about how everything in the Marvelman saga spins out of a singular moment the alien ship crashing to Earth, that led to the Zarathustra Project, that led to etc. etc.

Huey Moon isn’t part of that sci-fi premise. He’s a poetic addition. A man with tattered clothes and flowing hair who was born with the “Firedrake gene.” He’s there to round out the Pantheon, to provide another addition to the unlikely superhero team that has now formed in the story. He may have been included to add some diversity to the story—like many of the old sci-fi fables, this one tends to be lily white—or he may have been added just to provide more visual possibilities for what’s coming in Miracleman #15. Moon isn’t essential to the story, and he doesn’t even work as a symbol for the spark of humanity. He’s a god himself, though a mutant one.

“Pantheon” also gives us a few more plot points worth noting, all of which done exceedingly well in their short time on the page. (All of the first four “Olympus” chapters are only 16 pages each, and yet they are packed enough to equal two or three of today’s contemporary comic book issues.) This issue also gives us the emergence of infant Winter as a speaking character. She said a few words in the previous issue, much to Marvelman’s surprise. But now the baby takes flight to Qys, where she wants to learn about what she can really do. And she tells her father to “not look so sad. It’s such a lovely universe.” Then she’s off into space, alone.

Earth is, according to the narrative we heard from the Qys and the Warpsmiths, an Intelligent-Class world because of the presence of Winter. One wonders if her departure explains the unintelligent atrocities that will soon be committed in her absence.

Besides Winter’s words, we also get the “burial” of Mike Moran, as Marvelman transforms one final time, then places a pile of rocks on top of his human clothes, along with a handwritten epitaph for the man he once was. That’s the last vestige of Marvelman’s humanity, in a two-page spread by John Totleben. It is Marvelman ascendant, but reluctantly, sorrowfully so.

And, finally, Kid Marvelman gets loose. Johnny Bates says his magic word, under the duress of school bullies, and heads soon fly. Literally. The violence that follows only lasts for two pages, but it’s a mere precursor of what’s to come in the next issue. And this is where John Totleben turns from an artist able to depict elegant, moody science fiction fantasies, into an artist who will have drawn one of the most violent and horrifying sequences in comic book history.

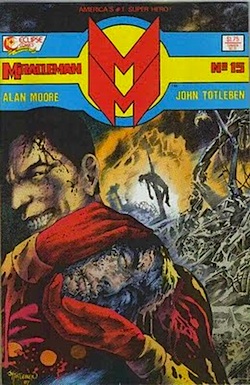

Miracleman #15 (Eclipse Comics, 1988)

If you’re looking to track down single issues of Alan Moore’s run on Marvelman, this one issue will be the hardest to find, or at least the most expensive. I don’t know that it was printed in less quantity than issue #14 or #16, but this is the one with the final battle between Marvelman and Kid Marvelman. It’s one of the most disturbing comics ever created. It’s a vile disgusting condemnation/celebration of superhero violence (take your pick). It’s the one everyone wants. You can decide what that says about our society.

If Moore’s Marvelman saga is what almost every superhero comic book wants to be today (with its violent “realism” and shocking revelations and grandiosity), and that certainly seems to be true, then Miracleman #15 is what every superhero fight scene wishes it could be, but can’t. Because superhero comics—almost all of them—are meant to continue. They can’t really end. The franchise must live on, whether it’s a corporate commodity or a self-published creator’s chance at building a larger audience (and selling the rights to Hollywood). And this is a final battle. This is the end.

The Thor comics may have had various “Ragnarok” stories—even the recently-completed Fear Itself event at Marvel proved itself to follow the Ragnarok model—but none of them come close to Miracleman #15, which details the devastation of London, the gruesome deaths of hundreds of civilians (and many more implied deaths), and a two-page spread that, even in it’s the black-and-white original linework, is still shockingly violent.

John Totleben has mentioned that the inspiration for his depiction of superhero-ravaged London came from Goya’s Disasters of War series. Goya haunts “Olympus” from beginning to end.

There’s not much to say about this issue. It’s brutal. Characters (and plenty of strangers) die horrible deaths at the hands of the former kid sidekick, the former Johnny Bates. In his dying moments, Aza Chorn teleports Kid Marvelman into a steel girder, forcing him to say his magic word to escape the pain. The hero of the series, Marvelman—who, by the way, has done practically nothing that would be considered heroic by any standards, throughout the whole run—merely cleans up the mess. He snaps young Bates’s neck. The hero commits murder to prevent it from happening again.

Then again, Kid Marvelman, at the beginning of Moore’s run, was perfectly content to use his powers to satisfy his own greed. He was no monster, just a selfish man with the powers of a god. It wasn’t until provoked by Marvelman, back in those opening chapters, that Johnny Bates’s alter ego turned into something terrible. In this issue, we’re left with a Marvelman sitting on wreckage and bones, holding a skull in his hands. But in the case of this Hamlet, it’s not a matter of what he should do, it’s a matter of facing what he has done.

Marvelman is as responsible for the death and destruction as anyone else. It’s the culmination of the superhero ideal—the ultimate battle between good and evil—but humanity pays the price, and only the gods remain.

The story for the issue, by the way, is titled “Nemesis.” Nemesis, the agent of the gods who destroys those who show hubris. Who is the one with hubris here? Is it Kid Marvelman? Marvelman? The audience who would identify with a costumed superhero and hold such power fantasies close to their hearts? Alan Moore himself, confronting post-Watchmen critical acclaim and his newfound status as the Greatest Comic Book Writer in History? Maybe all of the above.

What is clear, is that Moore and Totleben find the gods more interesting than the humans, though without the humans there would be nothing to show the power of the gods. No point of comparison. Nothing for the gods to think they’re greater than.

Miracleman #16 (Eclipse Comics, 1989)

Moore concludes his run with chapter six of Book Three, in a story named after the entire story arc, “Olympus.” At 32 pages, it’s twice as long as most of the chapters published by Eclipse, and yet it’s an epilogue to what has come before. The climax has resolved. Kid Marvelman is dead. It’s time for utopia.

I’ll let Moore, through Marvelman’s captions, tell this part of the story, skipping around to the highlights:

“The Bates affair with forty thousand dead and half of London simply gone, exposed us to the world, and we planned how to deal with Earth overtly, having no chance now of working secretly we later learned that Russia had come very close to launching a preemptive nuclear strike against Great Britain, hoping to eradicate the superhuman threat before it came to menace them. So had America. So had red China, France and Israel. The reason they eventually chose not to do so was not based upon morality, but rather on a burgeoning conviction that such measures simply would not work.”

The pantheon—Marvelman, Miraclewoman, Phon Mooda, and Huey Moon—took their place as shepherds of a new world order. Economic units were broken down. The world’s nuclear arsenal was teleported into the sun. They eliminated currency. And crime.

The story goes into a bit of detail about how they managed to do all of that, in typical sci-fi utopian fashion.

And they built a new Olympus, with a new god joining the pantheon, a Qys named Mors, who assumed the role of Hades, and used advanced technology to capture the recently dead into robot bodies where they could live again. Big Ben was recast as the British Bulldog, and became a demigod in the new world. Winter Moran returned to Earth and supervised the eugenics plan, and a new race of superbabies was born.

Liz Moran returned, in a hearbreaking scene, drawn by Totleben as tiny inset panels amidst a field of blank white. Marvelman offers her a superhuman conversion—they’ve perfected the Gargunza process by now—but she declines. “You’ve forgotten what you’re asking me to give up,” she says, before throwing him out one last time.

Dystopian ideas begin to creep into the world. Fundamentalists gather together and give speeches. Amongst the underclass—for even in a perfect world, not everything is perfect—Johnny Bates lookalikes become a fad. Dissent brews, beneath Olympus. But the gods and demigods barely notice, in their shining castle above it all.

Only Marvelman, now in military state regal attire complete with side-slung cape and epaulettes, takes the time to look down, and to wonder.

And Alan Moore and John Totleben’s Miracleman run comes to a close, and Moore hands the series over to Neil Gaiman and a few issues come out and Eclipse shudders its doors and the rights to the series remains eternally bound in legal limbo, with Marvel now working to untangle it all.

Moore’s Marvelman saga, from its beginnings in Warrior #1 to its conclusion and epilogue in Miracleman #16 took eight years to complete. Though only a few hundred pages in total, with some messiness in the middle, artistically, it still stands as one of the most influential comic books of all time, even if most of the people who’ve seen its influence at play have never actually read Moore’s work on the series.

Does Marvelman and/or Miracleman still have vitality, then? Does it still work, all these years after informing every other superhero comic that has followed? It does. Even with its problems, it’s still far better than most of its offspring. More alive, and more devastatingly powerful. Beautifully terrible. Hauntingly tragic, even as it ends with its hero sitting on top of the world.

NEXT TIME: Early Alan Moore Miscellany The Star Wars stories!

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

Huey Moon does flow out of that single event, just in the other direction: the Qys ship that crashed was there to kill him. (Or possibly just to check his power level and only kill him if it was on the ‘burn planets/stars/galaxies level.)

And #15 has the biggest plot hole of the series: why the heck didn’t they get Huey or one of the aliens to get into speaking range and just say ‘Abraxas’? (The characters at some point, possibly in the post-Moore issues but possibly in the original as well, speculate on different override words that Gargunza might have had for each of them, but, really: the guy must have been worried about having at least all three of the originals, if not all five, coming at him at once, and every sylable eats up a few seconds that he might not have. One word for all of them is the only way that makes sense for that safeguard.)

I too thought about that override word. You’d think they’d at least have tried it.

When Olympus was first being published, I was blown away by its literary stylings. I found Neil Gaiman’s run afterwards to be rather plain by comparison. Then I came back and re-read the whole run of Miracleman a decade or two later, and found a transformation in my reactions: Moore’s writing seemed a bit overblown and — there’s really no other word — pretentious; while Gaiman’s shone with imaginative extrapolation, solid storytelling, and well-drawn human characters.

“…Eclipse shudders its doors…”

I kept reading that over and over until I realized you meant “shutters”. As a victim of random homonym attacks, I sympathize.

Great write-up. I vaguely knew of this series by Moore, and now I want to read it. Unfortunately, unless there’s some sort of omnibus released, I won’t be able to.

I should perhaps add that, taking their body of work as a whole, I rate Alan Moore somewhat higher than I do Neil Gaiman — I think that “genius” (not a word I use lightly) is not too strong a description for Moore, while I think of Gaiman as merely excellent. (Merely!) This one particular work of Moore’s has simply not aged as well as I had hoped it would.

David @2: I had the same reaction to Moore’s prose in book 3. I’m not sure “pretentious” is the word I would use, though. I’m guessing that Moore meant it to come across as weird and mannered– that he wasn’t trying to convey “this is profound” so much as “this is being narrated by Marvelman, a strange and kind of old-fashioned dude with [accurate] delusions of grandeur.” MM is the only one who talks that way, and he’s supposed to be really out of touch with normal human thinking by that point (as Liz says). I think that was the intention… but those passages still come across to me as clumsy and excessive. Gaiman may have avoided this in The Golden Age by never giving us any internal monologue from MM– we only see him from the outside as this unknowable creature.

Jeff: Hah! I have a host of problems with #15’s plot, and the Abraxas thing never even occurred to me. My questions: 1) Why jump into the fight without any sort of plan? 2) Why just stand around and watch Marvelwoman get beat up? 3) Why does Phon Mooda do nothing at all in the fight? The previous issue clearly identifies her as a warrior. 4) Why doesn’t Moon try directly exploding Bates? 5) Why does Aza Chorn try attack after attack, each more powerful than the next? I mean, the text gives no hint that the successive attacks are harder for him to do, so why not just launch into the most devestating first? 6) Why doesn’t Aza Chorn teleport Bates somewhere else? The text makes a fuss about him not really knowing anywhere on Earth but London, but surely he knows many locations which are not on Earth? 7) Why kill Johnny?

I’m not saying one can’t come up with excuses to answer all of these questions: surely there are many no-prizes to be won. But it seems wildly sloppy that they have to be asked at all.

The crazy thing is, for all that, it’s still a really, really powerful issue.

(Though I’m reading Book 4 now, and agree that Gaiman’s writing shines. But it’s definitely deriviative in that it’s almost completely filling in on details that Moore created, if you know what I mean.)

Also, quick survey: Is the world issue #16 leaves us with supposed to be a utopia or a dystopia?

Tim: I’ve read a lot of commentary on the recurrence of sexual assault against women in Moore’s writing, and I don’t want to rehash it since it can easily devolve into something like “Q. If a writer depicts [common bad thing in life], how can you tell if he’s decrying it or getting off on it? A. Well I think it’s _____, because that’s just the feeling I have about this writer”… which never illuminates anything.

But in this case, it’s worth mentioning that Avril isn’t the only such victim in the story; the other one is Johnny Bates. You sort of glossed over this by just saying “duress,” but Bates is being raped when he finally lets Kid Marvelman loose. And there’s a huge difference in how Moore presents these two scenes and their consequences. Avril has distanced herself from the abuse and claims to have laughed it off, and we don’t see what happened, just a suggestive panel from Gargunza’s fantasy comic. Johnny’s ordeal happens in the real world, and he snaps immediately, says “I can’t take this”, and knowingly does the worst thing he can do.

I think the contrast was intentional, but it could be read in a few ways. You could say Johnny blows up because rape is just worse for a boy than for a girl– a very common assumption in popular culture, probably not what Moore believes, but certainly for a kid from the 1960s it would seem like the ultimate unacceptable thing. Or: Avril protected herself with imagination, but when Johnny tries to escape into his inner world, there’s nothing in there except his own angry self (literally– those panels show Bates alone in a black void). Or: Avril took her powerlessness for granted since she hadn’t known much else, but Johnny had had half a lifetime as the ultimate privileged adult, a rich and literally invulnerable man. I think those are all interesting readings, although for me the whole thing is hampered by the very minimal characterization of Marvelwoman; she’s almost as much of a flawless cipher as Winter.

Quite an interesting read. I just wanted to point out, despite the author’s prerogative and what came first and all that, I much prefer the name Miracleman to Marvelman. I shall explain by examining the vast difference between marvels and miracles as I understand those words:

A marvel, while exquisite and wondrous and maybe most triumphant example of man’s work, is something that can be explained as a phenomenon of the natural world. A miracle is not. It’s the action of a force beyond everything humanity can ever hope to be or even understand, making the impossible possible.

Moore, as you mention above, tells a story about the gods’ inhumanity rather than godlike humans. It’s a very good one, too – I still can’t decide if what Miracleman and the gang does to the world is good or bad. And I think the “Miracle” part of the name works well to convey that particular theme, maybe precisely because the controversy draws attention to it.

Jenny, I think that the tonal difference between the Chuck Beckum-illustrated issues and the ones which followed actually mark a transition from Moore continuing his Marvelman story from Warrior and writing something new, Miracleman. The themes of godhood and miracles really only come to the fore in the childbirth issue, and then of course they’re the center of Book 3.

The Warrior stories and the first few Eclipse ones are still about marvels — remarkable things in the normal world. But by “Olympus”, the story is about miracles, events which change the meaning of everything around them and redefine the world. Moore is aware enough of language to have been influenced by the change in the protagonist’s name.

Thanks, re-reading your re-reading of MM brings a tear to my eye. Was 1987/1988 that long ago?

Did anyone notice that Miracle-dog (Gargunza version) appeared in the Avatar movie?