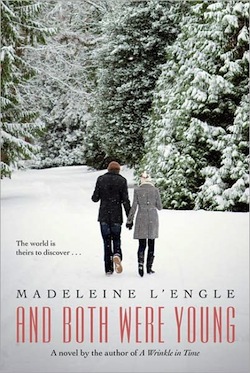

After Madeleine L’Engle delivered the manuscript of And Both Were Young to her publishers in the late 1940s, they asked her to remove material “inappropriate” for a teenage audience. She did so, an early step in a career that would soon be focusing on young adult novels, with occasional forays into adult novels. In 1983, she was able to capitalize on her popularity and have the book reprinted with those “inappropriate” elements restored.

Not that anything in the 1983 And Both Were Young feels particularly shocking. L’Engle’s foreword to the restored 1983 edition only notes that death and sex were considered unmentionable subjects for 1940s young adult literature, resulting in a “sanitized” manuscript. I have to say, the references to sex and death in even the 1983 edition are pretty sanitized—the Anne of Green Gables series has raunchier moments—and this book contains nothing objectionable for contemporary readers, suggesting that L’Engle’s publishers were cautious indeed.

Anyway. The book.

And They Were Young is the story of Philippa Hunter, called Flip, a young girl who has recently lost her mother in a car crash, sent away to a boarding school in Europe a few years after World War II as her father travels the world, to heal emotionally and illustrate a couple of books. Flip is miserable, missing her father and terrified that he is going to marry a woman who she despises. Fortunately enough, she meets a boy named Paul, who has no memory of his past, but is good looking and charming and an excellent distraction. (I’m assuming that a scene where they—squeak—meet alone in her bedroom in the dark was one of the removed elements, although neither of them take any real advantage of this moment.)

The less successful part of the book focuses on Paul and his attempts to regain his memories; he has forgotten most of his life, it turns out, because he was in a concentration camp, and wanted and needed to forget. Fortunately, most of the book focuses on Flip learning to accept the school and her friends and become considerably less self-absorbed, and on Flip, initially the isolated loser of the group, winning acceptance from her peers.

The book is loosely based both on L’Engle’s own memories of attending boarding schools in Switzerland and on the girls boarding school stories highly popular at the time. L’Engle, to her credit, does not offer up mere clichés, but Flip’s classmates do include the class clown (here combined with the class rich girl), the snob, the gossipy girl, the serene and competent class president that everyone admires, and so on. Naturally, Flip is forced to practice in quiet and receive secret lessons from a teacher and Paul so that she can stun the school with her competence. And so on.

But some small elements do make the book stand out. For one, Flip’s main issue with the school is not the school itself or homesickness, but that she can seemingly never be alone, and for someone still mourning her mother and needing space, this is a serious problem. (She ends up spending significant time hiding in the school chapel, which in later L’Engle books would be the beginning of a religious theme, but here is genuinely just used as a hiding space.) For two, a small scene later in the book about heroism, and its aftermath, draws on World War II to gain some real power.

L’Engle readers may be surprised by this book. It doesn’t necessarily sound like a L’Engle novel, and it avoids her usual focus on religion and science, found even in her mainstream novels. It also contains a character who is—shockingly for L’Engle—content that her parents are divorced and comfortable with the thought that they are sleeping around. (Some of her later characters would voice near hysteria at the mere suggestion that their parents might be committing adultery.)

But it does feature the intelligent, socially unsure and awkward teenage protagonist that would become a staple of her work. It also features several characters who continue on, despite sorrow and severe trauma, continuing to find joy in life, another staple. And it contains much of the warmth that would appear in most—not all—of her later works. If considerably lighter (even with the concentration camp and escaping from Nazi Germany subplot) than most of her later work, this is still a happy, satisfying read, giving L’Engle the foundations she needed to produce her later novels.

Mari Ness reads a lot. She lives in central Florida.

You know, I love Madelene L’Engle. It’s sad we will never get a resolution to some of the story threads she set up, but most are good where they lay. I have to say I didn’t read this particular novel, as I stuck to her Time books, which were my favorite.

Hoping this re-read continues further to the other books!

@Loialson — The reread will include all five of the Time books as well as some of her other, more mainstream books.

My edition was printed in 1956; now I’m very curious to know what I’ve missed!

This book isn’t a fantasy with time-travelling unicorns, but it is the other type of fantasy, a wish-fulfillment story, in which the unpopular girl makes friends and becomes a champion skier, and it looks like her father will choose the right person for her future stepmother. That was probably why I liked it so much as a child; like Flip, I was unpopular, and I didn’t overcome it as easily as she did.

I still like the book, though I can see some flaws. For one, the idea that the man who claimed to be Paul’s father had made a “profession” of finding people who didn’t know who they were – how many such people could there be? And how many of them were lucky enough to have foster families who cared about them?

Then there’s the author detemination not to mention Jews when writing about concentration camps, gassing, “lost children”, and the like. I think the character Jacqueline Bernstein is meant to be Jewish, but this is all we hear about her wartime experiences:

“Erna’s German, isn’t she?” Paul asked.

“Yes,” Flip answered quickly, “but Jackie Bernstein’s father was in a German prison near Paris for six months until he escaped and Erna is Jackie’s best friend.”

…which rather whitewashes over how the entire family would have been targetted by the Germans’ Final Solution

@Julie_K – :: nods :: I think the text is fairly ambiguous about whether or not Jacqueline is Jewish – on the one hand, yes, her filmmaker father was imprisoned, and although their name is “Bernstein” they live in Paris. On the other hand, her father wasn’t sent to a concentration camp, but just to a prison “near Paris.”

The text does, however, go out of its way to identify Paul’s father as a member of the minor landed French gentry who worked as a writer in the French Resistance, who ended up killed in the gas chambers for political not genocidal reasons. (It’s not clear if Paul’s mother was Jewish, but Paul’s father was not.)

The general sense I get is that L’Engle and her characters were still processing this aspect of the war; Flip even admits that she feels it, but doesn’t really know it.

An enjoyable book. I liked the fact that L’Engle resisted the opportunity to tie it all up with a bow and make Flip’s dad marry Mrs. Perceval. (It would almost certainly be a feature- perhaps the opening scene of Book 3 in the [never-written] series.)

I must say, her dad is a rather irritating character. ‘No, Flip, I can’t come see you ski, even though I’m only a few hours away.’ Plus his dependence on Mrs. Jackman when it’s clear that Flip dislikes her, even to following her recommendations for a school- couldn’t he get off his cloud and find one for himself?

Just finished reading this for the first time and found it delightful. I’d only read the Wrinkle in Time series when I, myself, was young, and I think that I would have treasured this one as well.

In some ways , it actually made me think of Twilight, if only in the way that it seems to effortlessly push some of the same emotional buttons without the squick of some of Twilight’s questionable moral lessons.

Yesterday’s comment got moderated, so let me redo it without the link.

Some excellent YA books dealing with post WWII- especially in Germany- were written by Margot Benary-Isbert in the 1950’s. I highly recommend them.

@christiana Ellis — In the sense of being a wish-fulfillment fantasy set in a high school I guess it’s kinda like Twilight, although I don’t get the same sense of either destined lovers or sparkling vampires. And now that I think about it the protagonists share some similar issues in the beginning — clumsiness and a need/desire to support their fathers emotionally.

So. Team Flip, then!

@Pam Adams – You’re just determined to make my reading list even worse, aren’t you?

@MariCats,

Turnabout is fair play, you know.

Pam Adams — I LOVE the Benary-Isbert titles, I’m sure they’re all OP, but so worth tracking down! The Ark came out in a US paperback, shouldn’t be too hard to find, for those interested in realistic post-WWII fiction set IN Germany. I wanted a Great Dane for a very long time after reading these!