To be honest, when I picked these three slim volumes up yesterday I wasn’t expecting them to be as good as I remembered them. The Prince in Waiting, (1970) Beyond the Burning Lands (1971) and The Sword of the Spirits (1972) were books I read first when I was ten at most, and which I read a million times before I was fifteen, and haven’t read for at least twenty years—though they’ve been sitting on the shelf the whole time, though the shelves have moved. I was expecting the suck fairy to have been at them—specifically, I wasn’t expecting them to have the depth and subtlety that I remembered. I mean they’re only 150 pages long—450 pages didn’t seem enough space for the story that I remembered. It barely seemed enough for the world.

However, I was pleasantly surprised. These really are good books. They’re not much like children’s books and they’re not much like science fiction as it was being written in 1970, but my kid-self was quite right in adoring these books and reading them over and over.

They’re set in a world generations after a catastrophe, but at first it looks like a feudal fantasy world. The influence is clearly Wyndham’s The Chrysalids—but Christopher takes it in a completely different direction and tells a much better story. We have a world where, weirdly, it isn’t nuclear war that has caused destruction and mutations but the explosion of volcanoes in Wales. Christopher stresses in each volume that this was a perfectly natural catastrophe—and I wonder in fact if this is the far future of the world of A Wrinkle in the Skin. (Despite this, as a child I ignored this and assumed it was post-nuclear, because I knew what I was afraid of, and I had read Wyndham.) Ignoring this weird detail and moving swiftly along, we have true men, dwarfs and “polymufs”—dwarfs are short and given to crafts, whereas polymufs (polymorphs) can have any mutation and are forced to be servants.

Christopher immediately thrusts us into the world Luke knows, a world of dwarf armourers and polymuf servants and warring city states, and a contest that a fourteen year old boy desperately wants to enter and cannot. Luke Perry is impetuous, bad tempered, given to depressions, not all that curious, and he really really wants to win. He’s not a typical narrator for a book aimed at children, but he’s our first person guide through this world. He accepts the religion of the Seers and the Spirits—when I first read these I had absolutely no idea that Spiritualism wasn’t something Christopher made up with the rest of it. (Come to that, the first time I went to Hampshire I was absurdly excited to see the names of the warring city states of these books as signposts pointing to real places.) We learn with Luke that machines are not evil and some people want to bring back science.

Almost all the characters of significance are male. I didn’t notice this when I was a child, obviously—give me a boy to identify with and I was away. But we have a couple of nice wives and one villainous one, and a couple of young women who Luke doesn’t understand at all and who might, were they allowed a point of view, be more interesting than they seem from this angle. Oh well. It was a different time.

One of the things I loved about these books as a child was the wonderful scenery. There’s the world, there are mutant monsters, there’s a journey with savages and smoking hot ground and ruined palaces. I know I read Beyond the Burning Lands first and it’s the one that’s most full of these things. But I also loved the bit of them I described in the title of this post as “betrayal and honour.” They’re full of it. It’s the story Christopher has chosen to tell in this world, and it holds up very well. In Mary Renault’s The Mask of Apollo, two characters reading a play say “It’s not exactly Sophocles, except where it is Sophocles.” I could say the same about these—they’re not exactly Shakespeare except where they are Shakespeare. But the next line in the Renault is “If you’re going to steal, steal from the best.” When I first read these I hadn’t read Shakespeare, and they helped give my mind a turn towards it. And anyway, why not have a taunting prince send toys to a young man newly come to power?

The books are full of vivid imagery, much more so than Christopher’s adult novels. They also have passionate human relationships on which the entire story hinges:

I knew there was nothing I could say to bridge the chasm between us. We called each other cousin, and were in fact half-brothers. We had been friends. We could not become strangers. It left one thing; we must be enemies.

In any standard SF novel in 1970 set in a world like this, science would triumph and the hero would get the girl. This is a much darker story, and strangely much more like some kinds of fantasy that have developed in the time in between. I didn’t like the end as a child —it wasn’t the way stories were supposed to come out—but now I admire it.

I mentioned that I read Beyond the Burning Lands, the middle book, first. I bought it from a wire rack in a seaside newsagent one summer holiday. I don’t know if you remember those racks of books, they’ve mostly disappeared now but you sometimes see them in airports. These days they are full of bestsellers, but in the seventies they often had one section of children’s books and one of SF. Before I knew what SF was I read Clarke’s Of Time and Stars and Amabel Williams Ellis’s Tales From the Galaxies. I bought Beyond the Burning Lands with my own 25p and read it in the car in the rain—and finished it that night with a flashlight under the covers. I bought the first and the third books the next Christmas in Lears in Cardiff, which was the next time I was in a bookshop. This is how reading children who don’t live near bookshops find books. This is why libraries have to be funded, and this is why schools need libraries, and this is why physical books going away could be a problem—not a problem for reading adults who can prioritize their own budgets, a problem for reading kids. I waited six months for The Prince in Waiting and The Sword of the Spirits, and if I’d had to have a device that cost the equivalent of $100 and a credit card I’d have had to wait until I was eighteen. It makes me reach for my inhaler when I think about it.

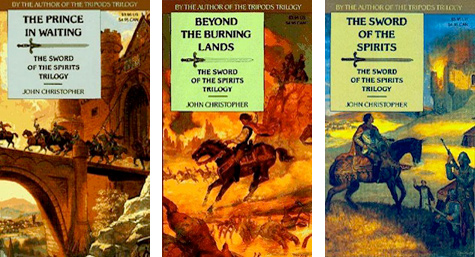

In any case, these remain excellent books, in a style perhaps more familiar in fantasy than in SF. The only bit the suck fairy has been at is the 1970’s Puffin covers, which I remembered as green, red, green, and which I now see are absolutely horrible. I commend them to your adult attention.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I haven’t read them in thirty years – like you, because of fears of the suck fairy having visited. Found them in my library, which served a small town in the center of Ireland, Cashel with circa 2,000 inhabitants, but nonetheless had an excellent collection of Gollancz yellowbacks etc. Glad to hear that they stand up. Some bits still seem extraordinarily vivid to me – the communal nests of semi-intelligent rats, and the final line of the third book (unless time has garbled it) – “But I will have no son.”

I just got them from the library- let’s hope for a rainy weekend with lots of reading time.

I read two of these books in my middle school library at age 12, but moved shortly thereafter and never remembered the titles or the author. My memories of the series are very dim, but I recall being fascinated. Thanks for revisiting these books–I’m off to find them now!

I utterly loved the Tripod books, and The Guardians, but for some reason I never got into this trilogy.

The books were right there in the elementary school library, with “Christopher’s” other YA titles, and I know I started reading one of them. But . . . what didn’t click?

If I got my hands on the set today I’d certainly read them.

The covers pictured here are so much nicer than the weird UK 70s covers on my copies!

I think I may have to pick these up. My queue is kind of full at the moment, but they sound wonderful.

What really intrigues me is the idea that these are NOT post-nuclear war. A while back, I was reading a bunch of sci-fi from the 70s and 80s, and it seemed like just about every book started with a nuclear war. I understand why, but looking back, everytime I read that beginnning, I would roll my eyes and think, “Again?” Kudos to Christopher for doing something different.

The ones I read back in the 70’s, which I got from my local library, had these covers:

I, too, have been fearful that fairy (and some others) may have visited.

Sadly, that library no longer has a separate SF section. It’s all mixed in together. Alpha by author. Sigh.

But Wiredog, that was how I found a bunch on interesting things in Jr. High – reading my way (very methodically) through the fiction section from author A to … I made it to Philip Wylie before I changed schools! So I found Christopher, and Heinlein, and Empress From the Stars as well as a fistful of gothic and romance writers and some old friends (Joan Aiken’s Nightbirds on Nantucket, when I’d been to Nantucket, was fabulous beyond belief!) –

The point being, that I wouldn’t have made into an SF section, but I would read anything if it was the next thing on the shelf. So there is one vote for integration…

I had a “book buddy” in high school and we traded worn SF paperbacks back and forth. She loaned me this trilogy when I was in high school and I loved it, much more than I ever did anything else by Christopher.

I recall really liking the post-apocalyptic landscape which initially masquerades as fantasy. Good stuff, and I’m glad to hear that they hold up today, even with the downer ending.

A lovely series- the world reminds me of the one in Pangborn’s Davy.

Jo, were you aware that Sam Youd (AKA John Christopher)died just a few weeks ago? I went to look up his bibliography on Wikipedia, and was surprised to find that he’d died on February 3rd, 2012.

:(

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sam_Youd

Awesome Aud: Yes, I posted an obituary just two days before posting this post, and it was hearing the sad news that caused me to re-read these books now.

“Awesome Aud: Yes, I posted an obituary just two days before posting this post”

Duh! How did I miss that? Just call me not-so-awesome Aud…

Luke’s a rather nicely-drawn unreliable narrator. He admits that he’s clueless about psychological interactions, so it’s sadly plausible that he fails so disastrously in his interpersonal relationships while being a tough, competent leader.

I reread them last week, after a thirty-year gap, and a LOT of his motivations and misunderstandings were much clearer to me in regards to Blodwen, especially.