My experience when reading most articles in The New Yorker is usually one of rapt contradiction. Whether it’s a Susan Orlean essay on the history of mules, a piece about Internet dating, or an undercover exposé of the Michelin Guide, I often get the sense that the writer is sort of squinting sideways at the subject in an effort to render it interesting and intelligently amusing. This isn’t to say the articles aren’t great, just that the erudite tone makes me sometimes think they’re sort of kidding.

To put it another way, I sometimes feel that articles in The New Yorker are written to transform the reader into their mascot, the dandy Eustace Tilley. The prose feels like you’re holding up a smarty-pants monocle to check out a butterfly.

With the debut of The New Yorker’s first ever “Science Fiction Issue” the periodical of serious culture is holding up its monocle to our favorite genre. The results? As the Doctor might say, “Highbrow culture likes science fiction now. Science fiction is cool.” But do they really?

There’s a ton of fiction in the Science Fiction Issue of The New Yorker but, not surprisingly, the pieces that might appeal to more hardcore “Sci-Fi” fans are the non-fiction ones. There’s a beautiful reprint of a 1973 article from Anthony Burgess in which he attempts to explain just what he was thinking when he wrote A Clockwork Orange. This essay has a startling amount of honesty, starting with the revelation that Burgess overheard the phrase “clockwork orange” uttered by a man in a pub and the story came to him from there. He also makes some nice jabs at the importance of writerly thoughts in general declaring the novelist trade “harmless,” and asserting that Shakespeare isn’t really taken seriously as “serious thinker.”

But the contemporary essays commissioned specifically for this issue will make a lot of geeks tear up a little bit. From Margaret Atwood’s essay “The Spider Women” to Karen Russell’s “Quests,” the affirmations of why it’s important to get into fiction, which as Atwood says is “very made up,” are touching and true. Russell’s essay will hit home with the 30-somethings who grew up on reading programs which rewarded young children with free pizza. In “Quests” the author describes the Read It! Program, in which most of her free pizza was won through reading Terry Brooks’s Sword of Shannara series. When mocked for her reading choices, she heartbreakingly describes filling in the names of other mainstream books on the ReadIt! chart instead. But ultimately, Karen Russell declares, “The Elfstones is so much better than Pride and Prejudice” before wishing well the geeky “children of the future.”

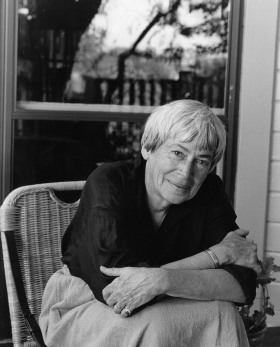

Ursula K. Le Guin turns slightly more serious with a great piece about the so-called “Golden Age” of science fiction, a time in which Playboy accepted one of her stories for publication and then freaked out a little when they found out she was a woman. The eventual byline read, “It is commonly suspected that the writings of U.K. Le Guin are not actually written by U.K Le Guin, but by another person of the same name.” Her observations about some of the conservatism in SFWA’s early days are insightful and fascinating and also serve to remind you just how essential Le Guin is to the community. Meanwhile, China Mieville writes an e-mail back in time to a “young science fiction” fan who seems to be himself. This personal history is a cute way of both confessing his influences and wearing them proudly. It also contains the wonderful phrase “the vertigo of knowing something a protagonist doesn’t.”

Zombie crossover author Colson Whitehead appropriately writes about all the things he learned from B-movies as a child, while William Gibson swoons about the rocket-like design of a bygone Oldsmobile. Ray Bradbury is in there, too.

A perhaps hotter non-fiction piece in this issue all about Community and Doctor Who. As io9 previously pointed out, writer Emily Nussbaum kind of implies the current version of Doctor Who differs from its 20th century forebearer mostly because it’s more literary and concerned with mythological archetypes and character relationships. Though some of this analysis feels a little off and bit reductive to me, it is nice to see Who being written about fondly in The New Yorker. However, the best non-fiction piece in the whole issue is definitely “The Cosmic Menagerie” from Laura Miller, an essay that researches the history of fictional aliens. This article references The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, and points out the notion of non-terrestrial adaptations are mostly the result of a post-Darwin world.

But what about the science fiction in the science fiction issue? Well, here’s where The New Yorker remains staunchly The New Yorker. All of the short stories are written by awesome people, with special attention to Jennifer Egan’s Twitter-ed story “Black Box.” But none of them are actually science fiction or fantasy writers. Now, I obviously love literary crossover authors who can identify as both, and as Ursula K. Le Guin points out in the “Golden Age” essay, people like Michael Chabon have supposedly helped to destroy the gates separating the genre ghettos. But if this were true, why not have China Mieville write a short story for the science fiction issue? Or Charlie Jane Anders? Or winner of this year’s Best Novel Nebula Award Jo Walton? Or Lev Grossman? Or Paul Park?

Again, it’s not that the fiction in here is bad at all (I particularly love the Jonathan Lethem story about the Internet inside the Internet); it simply doesn’t seem to be doing what it says on the cover. Folks within the genre community are becoming more and more enthusiastic about mainstream literary folks by celebrating the crossover and sharing “regular” literary novels with their geeky friends. One of the aims of a column like this one is to get science fiction readers turned on to books they might not otherwise read. (China Mieville mentions this is a problem in his New Yorker essay.) But the lack of inclusion of an actual honest-to-goodness science fiction (or fantasy!) writer made me feel like we weren’t getting a fair shake.

In the end, when Eustace Tilley holds up his monocle to a rocketship, the analysis is awesome, readable, and makes you feel smarter. But Eustace Tilley can sadly, not build a convincing rocketship. At least not this time.

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com.

But none of them are actually science fiction or fantasy writers.

What madness is this? What is a science fiction/fantasy writer but a writer who composes works of science fiction and/or fantasy? It’s an especially silly claim as Lethem, who has published books with Tor and whose short fiction has appeared in SF/F magazines, contributes fiction to this issue.

I was also surprised that Lethem isn’t considered here as “a SF author.”

I appreciate the essays spotlighted here, but I would’ve also appreciated hearing more about the stories themselves and the authors who did write them.

Uh oh, I think I see the way this comment thread is going to go. And while N. Mamatas and DKT do point out the problem here (what makes someone an SF author besides authoring SF?), I think I see your point, Ryan Britt, and I think it’s a (semi-)fair point.

That is, the New Yorker seems to have tapped people whose literary bona fides are a little stronger than their SF bona fides. (Although, again, what’s a bona fide in this situation? I’d probably say “writing for Tor blog and going to SF cons,” in which case Lethem is whole-heartedly an sf writer.)

But I’m not so bothered by this (though I’m a little saddened, as you point out that some of these other authors didn’t get a shot–and where’s the Ted Chiang love?) as long as these writers are knowledgeable and thoughtful with the genre. (No Phil Roth alt history, please!)

And we might be journeying towards a time when sf as a genre–as a home territory–does disappear, and becomes merely another tool for all writers to use. As with all generic changes, something may be lost and something may be gained by such slipstreaming of sf.

I feel kind of torn about this issue as I loved parts of it and the article about Who made me feel like The New Yorker got fans, but in the last issue, there was an awful article about guilty pleasure reading. I feel like that article was more of the true New Yorker, which I do enjoy reading but not for genre issues. Not full on literary snobbery but as you said, kind of looking at genre sideways and not quite getting it. That article was meant to be all for reading mysteries/thrillers but came out being well they can be well written and they’re fine to read just balance them out with proper reading.

This issue felt like they were trying to go, we can do that but it just was uneven. They do better when they just do fiction or style, this isn’t really their realm.

@1 Nick

At this point, I really don’t think Lethem is in the SF camp. I love, love, love Lethem. And will talk about all the crazy alternate universe stuff from his last novel, Chronic City. BUT, he is a literary author and his first book was science fiction. Which I ALSO love. However, I will point out that you’ll never see it listed in the “also by Lethem” list in his other books.

Also your questions are not easily answered, and this entire column is an attempt to figure that stuff out. I may never figure it out.

@2 You know, I really probably should have. I suppose for some reason I reversed my polarity and actually went for the pieces I really remembered and enjoyed, rather than the stuff I felt like I HAD to cover. But the Lethem story is fantastic, and the Egan story is fun.

Ryan,

You just seem to have some sort of intuition about who is and who is not an SF writer, which strikes me as untenable. I would say that Lethem’s first few novels were surely SF, as was his McSweeney’s novelette. His post-Motherless Brooklyn novels featured magic rings and whatnot as well. Surely, one does not define a science fiction writer as “a writer who signs a slave-contract with a science fiction publisher and thus cannot ever publish anywhere else.”

Also, he was the guest of honor at Readercon in 2008, he’s written for Marvel Comics, his recent work as an editor includes editing the fiction and philosophy of Philip K. Dick, as well as co-editing a volume of Robert Sheckley stories (published this month), and his big essay collection is anchored by a tendentious piece in which he complains that a realist critic failed in his review of The Fortress of Solitude by not discussing the magic ring.

If he’s not an SF writer, there aren’t any SF writers. He also writes literary fiction. Big deal. Plenty of SF writers also teach school, write ad copy, teach martial arts, write mysteries, trade sex for table scraps, write software manuals, etc. How is it that writing literary fiction—which is best understood simply as writing work published in literary journals and read by people with an interest in literary fiction—a disqualifying activity?

My beef is, why not use a sf/f artist for the cover? I know the New Yorker has a look but you can’t tell me that someone like Sam Weber wouldn’t have been a great representative of the genre.

Jennifer “THE KEEP” “A VISIT FROM THE GOON SQUAD” Egan? As much as I object to the concept of us-ness, she’s one of us.

Er, also posted today, a post about one of the Freddy the Pig books — featuring talking animals taking a balloon trip and fighting criminals in upstate New York, so, fantasy — written, as it happens, by a writer, essayist and editor at The New Yorker.

What Nick Mamatas said. I can only imagine that Ryan hasn’t read, or forgot about, Amnesia Moon, Girl in Landscape, and As She Climbed Across the Table. And “you’ll never see [one of his SF novels] listed in the ‘also by Lethem’ list in his other books” is a statement about publishers, not about the writer.

@Nick and Eil

I think we’re quibbling about details here. I think we all agree. Lethem is awesome. I have read and love all of his books. He’s a crossover guy.

But you only have to think about it for one second to know he’s got no problem getting into The New Yorker anytime he wants; science fiction issue or not. Also The New Yorker audience is already familiar with him. All of the authors in the issue belong there and are great. I’m just saying they aren’t really introducing the readership to anyone who is exclusively in the science fiction community who ALSO might appeal to their readers. In short, it doesn’t seem like they pushed the boundaries with who was selected. I’m sure we can agree on that, right?

Fighting about whether the work is or is not genre is exactly what I’m interested in talking about all the time. Like I said, I think it’s a complex issue. However, when we’re talking about authors who everyone who reads the The New Yorker has already heard of, and not some awesome (very literary) hardcore science fiction writers, then I’m saying an opportunity for reader sharing has been missed.

@8

I love Jennifer Egan. She is one of the best writers alive. That’s why I wrote so favorably about Goon Squad last year. I wish I knew more science fiction fans who have read her.

@12 – Jennifer Egan is firmly marketed as a mainstream fiction author, not SF. So is Jonathan Lethem, for that matter.

As always, outside attempts to peer into the world of SF, or attempts by SF folks to venture out from the world of SF, are viewed with a bit of trepidation and skepticism. It is scary when people start rearranging the boxes that we use to store all our preconceived notions!

…here’s where The New Yorker remains staunchly The New Yorker.

Yes. Is this a criticism? Does running science fiction mean The New Yorker should suddenly turn into Astounding for the duration?

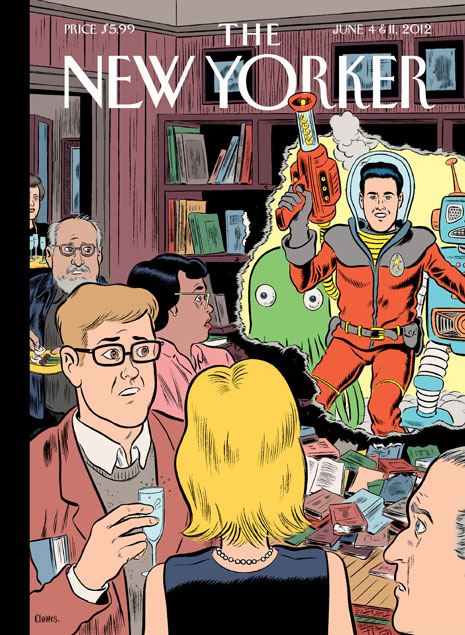

From the masthead, it looks like they did a reasonably good job of publishing the kind of science fiction The New Yorker would publish–and that goes for the cover illo as well. They’ve got one of the longest-running, most consistent brands in magazine publishing, and a well-established editorial identity; what else would they do?

The New Yorker‘s audience is clearly the guy on the cover who thinks that the intruder’s spacesuit is far too gauche for the gender studies mixer.

Ryan, this isn’t a quibble, this is just you changing your argument. Which is fine; I intervened in the hope that you would change your argument. But you should also acknowledge that “not” SF writers and “not exclusively in the…community” are too different things. Incidentally, I am having a hard time thinking of anyone exclusively in SF that would suit.

Re: the cover, I wasn’t crazy about it at first, but I’ve kind of grown to like it. It seems to basically show how science fiction, despite its perceived focus on ray-guns and weird aliens is “crashing the party” of the New Yorker and literary fiction in general. The presence of Dan Clowes in the New Yorker is itself something of a parallel achievement to the inclusion of SF or other “genre” writers. Some very good comics creators (Art Spiegelman, Dan Clowes, Seth, R. Crumb, Adrian Tomine, Jaime Hernandez) have been appearing quite frequently in the New Yorker in recent years. Indeed, this same issue featured a very good Tomine illo in the movie review section.

Just to expand on this a bit further, Clowes etc. are not part of the New Yorker stable of cartoonists. For a long time, the only cartoonists to get cover features were those who drew interior cartoons as well (e.g. Chas Addams, Helen Hokinson, etc.) This development is largely (I believe) due to the efforts of Françoise Mouly, the current art director.

Hm. I didn’t much care for the Lethem story; I did very much like “Monstro” by Junot Diaz. The Burgess essay (not a reprint actually, though written some time ago this was its first publication) was completely engrossing and fascinating.

“I often get the sense that the writer is sort of squinting sideways at the subject in an effort to render it interesting and intelligently amusing.”

You have just described all of literary criticism ;p