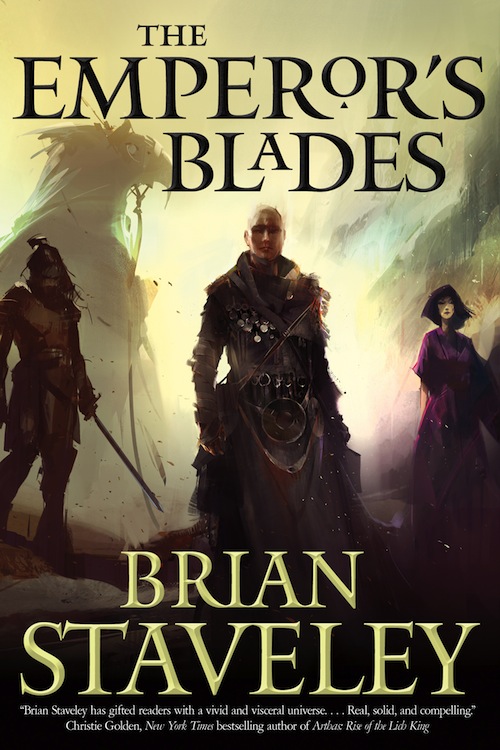

Brian Staveley’s The Emperor’s Blades, book one of Chronicles of the Unhewn Throne, is available from Tor Books in January 2014, and a new chapter of the book will appear on Tor.com by 9 AM EST every day from Tuesday, November 12 to Monday, November 18. Keep track of them all here, and dig in to Chapter One below!

The emperor of Annur is dead, slain by enemies unknown. His daughter and two sons, scattered across the world, do what they must to stay alive and unmask the assassins. But each of them also has a life path on which their father set them, their destinies entangled with both ancient enemies and inscrutable gods.

Kaden, the heir to the Unhewn Throne, has spent eight years sequestered in a remote mountain monastery, learning the enigmatic discipline of monks devoted to the Blank God. An ocean away, Valyn endures the brutal training of the Kettral, elite soldiers who fly into battle on gigantic black hawks. At the heart of the empire, Minister Adare, elevated to her station by one of the emperor’s final acts, is determined to prove herself to her people. But Adare also believes she knows who murdered her father, and she will stop at nothing—and risk everything—to see that justice is meted out.

One

The sun hung just over the peaks, a silent, furious ember drenching the granite cliffs in a bloody red, when Kaden found the shattered carcass of the goat.

He’d been dogging the creature over the tortuous mountain trails for hours, scanning for track where the ground was soft enough, making guesses when he came to bare rock, doubling back when he guessed wrong. It was slow work and tedious, the kind of task the older monks delighted in assigning to their pupils. As the sun sank and the eastern sky purpled to a vicious bruise, he started to wonder if he would be spending the night in the high peaks with only his roughspun robe for comfort. Spring had arrived weeks earlier according to the Annurian calendar, but the monks didn’t pay any heed to the calendar and neither did the weather, which remained hard and grudging. Scraps of dirty snow lingered in the long shadows, cold seeped from the stones, and the needles of the few gnarled junipers were still more gray than green.

“Come on, you old bastard,” he muttered, checking another track. “You don’t want to sleep out here any more than I do.”

The mountains comprised a maze of cuts and canyons, washed-out gullies and rubble-strewn ledges. Kaden had already crossed three streams gorged with snowmelt, frothing at the hard walls that hemmed them in, and his robe was damp with spray. It would freeze when the sun dropped. How the goat had made its way past the rushing water, he had no idea.

“If you drag me around these peaks much longer… ,” he began, but the words died on his lips as he spotted his quarry at last—thirty paces distant, wedged in a narrow defile, only the hindquarters visible.

Although he couldn’t get a good look at the thing—it seemed to have trapped itself between a large boulder and the canyon wall—he could tell at once that something was wrong. The creature was still, too still, and there was an unnaturalness to the angle of the haunches, the stiffness in the legs.

“Come on, goat,” he murmured as he approached, hoping the animal hadn’t managed to hurt itself too badly. The Shin monks were not rich, and they relied on their flocks for milk and meat. If Kaden returned with an animal that was injured, or worse, dead, his umial would impose a severe penance.

“Come on, old fellow,” he said, working his way slowly up the canyon. The goat appeared stuck, but if it could run, he didn’t want to end up chasing it all over the Bone Mountains. “Better grazing down below. We’ll walk back together.”

The evening shadows hid the blood until he was nearly standing in it, the pool wide and dark and still. Something had gutted the animal, hacked a savage slice across the haunch and into the stomach, cleaving muscle and driving into the viscera. As Kaden watched, the last lingering drops of blood trickled out, turning the soft belly hair into a sodden, ropy mess, running down the stiff legs like urine.

“ ’Shael take it,” he cursed, vaulting over the wedged boulder. It wasn’t so unusual for a crag cat to take a goat, but now he’d have to carry the carcass back to the monastery across his shoulders. “You had to go wandering,” he said. “You had…”

The words trailed off, and his spine stiffened as he got a good look at the animal for the first time. A quick cold fear blazed over his skin. He took a breath, then extinguished the emotion. Shin training wasn’t good for much, but after eight years, he had managed to tame his feelings; fear, envy, anger, exuberance—he still felt them, but they did not penetrate so deeply as they once had. Even within the fortress of his calm, however, he couldn’t help but stare.

Whatever had gutted the goat did not stop there. Some creature— Kaden struggled in vain to think of what—had hacked the animal’s head from its shoulders, severing the strong sinew and muscle with sharp, brutal strokes until only the stump of the neck remained. Crag cats would take the occasional flagging member of a herd, but not like this. These wounds were vicious, unnecessary, lacking the quotidian economy of other kills he had seen in the wild. The animal had not simply been slaughtered; it had been destroyed.

Kaden cast about, searching for the rest of the carcass. Stones and branches had washed down with the early spring floods and lodged at the choke point of the defile in a weed-matted mess of silt and skeletal wooden fingers, sun-bleached and grasping. So much detritus clogged the canyon that it took him a while to locate the head, which lay tossed on its side a few paces distant. Much of the hair had been torn away and the bone split open. The brain was gone, scooped from the trencher of the skull as though with a spoon.

Kaden’s first thought was to flee. Blood still dripped from the goat’s gory coat, more black than red in the fading light, and whatever had mauled it could still be in the rocks, guarding its kill. None of the local predators would be likely to attack Kaden—he was tall for his seventeen years, lean and strong from half a lifetime of labor—but then, none of the local predators would have hacked the head from the goat and eaten its brain either.

He turned toward the canyon mouth. The sun had settled below the steppe, leaving just a burnt smudge above the grasslands to the west. Already night filled the canyon like oil seeping into a bowl. Even if he left immediately, even if he ran at his fastest lope, he’d be covering the last few miles to the monastery in full dark. Though he thought he had long outgrown his fear of night in the mountains, he didn’t relish the idea of stumbling along the rock-strewn path, an unknown predator following in the darkness.

He took a step away from the shattered creature, then hesitated.

“Heng’s going to want a painting of this,” he muttered, forcing himself to turn back to the carnage.

Anyone with a brush and a scrap of parchment could make a painting, but the Shin expected rather more of their novices and acolytes. Painting was the product of seeing, and the monks had their own way of seeing. Saama’an, they called it: “the carved mind.” It was only an exercise, of course, a step on the long path leading to the ultimate liberation of vaniate, but it had its meager uses. During his eight years in the mountains, Kaden had learned to see, to really see the world as it was: the track of a brindled bear, the serration of a forksleaf petal, the crenellations of a distant peak. He had spent countless hours, weeks, years looking, seeing, memorizing. He could paint any of a thousand plants or animals down to the last finial feather, and he could internalize a new scene in heartbeats.

He took two slow breaths, clearing a space in his head, a blank slate on which to carve each minute particular. The fear remained, but the fear was an impediment, and he pared it down, focusing on the task at hand. With the slate prepared, he set to work. It took only a few breaths to etch the severed head, the pools of dark blood, the mangled carcass of the animal. The lines were sure and certain, finer than any brushstroke, and unlike normal memory, the process left him with a sharp, vivid image, durable as the stones on which he stood, one he would be able to recall and scrutinize at will. He finished the saama’an and let out a long, careful breath.

Fear is blindness, he muttered, repeating the old Shin aphorism. Calmness, sight.

The words provided cold comfort in the face of the bloody scene, but now that he had the carving, he could leave. He glanced once over his shoulder, searching the cliffs for some sign of the predator, then turned toward the opening of the defile. As the night’s dark fog rolled over the peaks, he raced the darkness down the treacherous trails, sandaled feet darting past the downed limbs and ankle-breaking rocks. His legs, chill and stiff after so many hours creeping after the goat, warmed to the motion while his heart settled into a steady tempo.

You’re not running away, he told himself, just heading home.

Still, he breathed a small sigh of relief a mile down the path when he rounded a tower of rock—the Talon, the monks called it—and could make out Ashk’lan in the distance. Thousands of feet below him, the scant stone buildings perched on a narrow ledge as though huddled away from the abyss. Warm lights glowed in some of the windows. There would be a fire in the refectory kitchen, lamps kindled in the meditation hall, the quiet hum of the Shin going about their evening ablutions and rituals. Safe. The word rose unbidden to his mind. It was safe down there, and despite his resolve, Kaden increased his pace, running toward those few, faint lights, fleeing whatever prowled the unknown darkness behind him.

The Emperor’s Blades © Brian Staveley, 2014