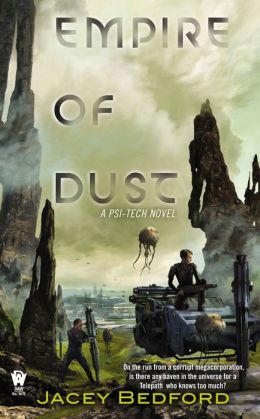

Empire of Dust is Jacey Bedford’s debut novel. When I consider how to describe it, the first word that comes to mind is “old-fashioned”: there is little to say this space opera novel could not have been published two decades ago, or even three, and it suffers by comparison to the flourishing inventiveness of Ann Leckie and Elizabeth Bear, James S.A. Corey and Alastair Reynolds.

Though it may be unfair to judge it by those standards.

Carla Carlinni is a telepath. She used to work for Alphacorp, one of the two giant corporations whose actions and influence control most of human space. But after discovering massive corruption—and being betrayed by her lover, Alphacorp exec Ari van Bleiden—she’s on the run. With van Bleiden’s enforcers on the brink of catching up with her, she falls in with navigator Ben Benjamin, who works for the Trust, Alphacorp’s rival: a man who has his own experiences with being on the wrong end of corporate corruption. After an awkward beginning, Benjamin comes to like and, mostly, to trust Carla. In order to get her away from her pursuers, he arranges for her to join the support team he’s leading for a new colony: a support team composed entirely of psionically talented people, for a colony being founded by a group of religious separatists who believe that telepaths are abominations who come from the devil—and so is modern technology.

Add to this one more small problem: Benjamin rapidly discovers that the original surveys for the colony failed to uncover the fact that the planet is a goldmine for a natural resource on which space travel depends—a finite resource, one that people kill for.

What could possibly go wrong? Van Bleiden is still on Carla’s trail, and Benjamin will shortly discover that not only can he not trust the colonists, he can’t trust the people who sent him and his team out in the first place. Oh, and someone has messed up Carla’s brain bigtime via psychic brainwashing.

And he and Carla appear to be falling love.

Space opera comes in several varieties. David Drake and David Weber typify its military end; Sharon Lee and Steve Miller’s work is characteristic of some of its more pulpish tendencies. Lois McMaster Bujold and C.J. Cherryh represent other strands, Vernor Vinge one too, and Iain Banks yet another. It’s a broad church, and one that in the last five or six years seems to have attracted a fresh influx of energy and enthusiasm—and innovative repurposing of its old furniture.

Bedford is not writing innovative space opera, but rather the space opera of nostalgia. There is, here, something that reminds me vaguely of James H. Schmitz: not just the psionics but a certain briskness of writing style and the appeal of the protagonists, and the way in which Bedford’s vision of the societies of a human future feels at least two steps behind where we are today. This is a vision of a very Western future, and one where it’s unremarkable for a married woman to bear her husband’s name; where the ecological ethics of colonising “empty” planets don’t rate a paragraph, and religious separatists can set out to found a colony on the tools of 19th century settlers: oxen and wagons, historic crafts and manly men whose wives will follow them on the next boat.

Don’t mistake me: there’s nothing wrong with a certain pleasant nostalgia. One of the purposes of entertainment is to please, after all. But I confess myself uneasy with too much unexamined reproduction of old-fashioned genre furniture: nostalgia in entertainment falls easily into the trap of confirming our existing biases, or at least uncritically replicating them.

It’s easier to pass lightly over the tropishness of a setting if a novel has a straightforward, fast-paced narrative structure and compelling, intriguing characters. Empire of Dust’s protagonists are compelling; its antagonists, less so. And Bedford has fallen prey to the classic debut novel problem of having too much plot for her space. Several narrative threads feel underdeveloped as a result—threads that might, given more space and more willingness to interrogate the underlying tropes, have been much more powerfully affecting. Although there are moments when Bedford begins to interrogate a trope or two, only to shy off from looking at them too deeply.

This is not to say that Empire of Dust is unenjoyable: Bedford’s prose is brisk and carries the reader quite sufficiently along. This a debut that shows a writer with potential to do better work, and one whose next effort I will look forward to with interest.

Empire of Dust is available November 4th from DAW

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.

I don’t know if I would use the word nostalgia, myself, since there are plenty of people who write Nostalgic Space Opera. But I grope for a word. Old school sounds wrote. Retro doesn’t quite capture it, since it doesn’t sound like the author is being consciously retro (a prerequisite) for this. “Old Style”?

But authors like McDevitt, and a bunch of the space opera published by Baen make me wonder if the majority of space opera is Old Style.

SF is far along to have a set of styles like jazz: trad, bebop, free, and people who don’t do styles.

Working in an established style, like space opera, is tough. Anyone can list the core works. But there is always room for variation. I have an LP with a killer version of a Charlie Parker composition (Scrapple from the Apple) on pennywhistle. Seriously, these guys own it.

I can also make a big list of space opera authors that don’t own it.

Leaving aside the use of Ms. Leckie as any sort of comparison, having an interesting plot and engaging characters within the typical Space Opera (such as Baen are excellent in prodicing) would betoken an author who would be interested in actually engaging their readers in an entertaining book. Thus this would be suggestive of a good read above all else.

It’s odd how rarely space opera seems to give any thought to its antagonists. The Expanse novels are some of the best “old-school” space opera around. It’s like reading a video game. (Or maybe video games have come a lot closer to playing like a proper literary space opera.) Fun characters and just enough of an eye for realistic science not to make it all completely unbelievable. (The slowdown in Abaddon’s Gate was an awesome use of gravity as a huge plot device.) But they’re really about the protagonists. I haven’t read Cibola Burn, but if you look at the first three books, the villains are a corrupt corporate executive, a mad scientist, a crazy warhawk admiral, another mad scientist, another crazy warhawk admiral, and oh, the daughter of the corrupt corporate executive.

A review that, ironically, reveals more about the writer’s biases than the book being reviewed. Like those of nearly every generation in history, the reviewer seems convinced that today’s values are automatically better than yesterday’s in every particular, instead of merely different, and that nostalgia is a codeword for regression.

Baloney.

First, I love to see a woman writer writing legacy-style pulp, hearkening back to the great adventure stories of yesteryear, where both women and men could both be heroes no matter whether they chose traditional roles or not. Forcing women into only one straitjacketed form of heroism, or worse, one straitjacketed form of protagonist non-heroism, seems hypocritical to anyone who believes in equal opportunity and fair depiction for all.

Second, depicting humanity as it is, and is likely to remain, in all its flawed glory, with its many cultures and many values, some traditional and some new and different, is the ultimate in “diversity.” Complaining that the protagonists don’t conform to a specific highly westernized postmodern ethic, and are therefore lacking, is the ultimate in neo-puritanism–the puritanism of the new, no-value values.

Or, even worse for an experienced reviewer, she’s fallen into the trap of going to a hamburger joint and complaining her hamburger doesn’t taste like pizza, confusing her subjective opinion with an objective evaluation.

But thanks for convincing me to pick up a copy. Sounds right up my alley.