Discovering an author’s body of work can be intimidating, especially for some one as prolific as Connie Willis. Willis, a multiple Nebula and Hugo Award winning author and a SFWA Grand Master, has written over 15 novels and dozens of short stories since the 1980s, with no signs of slowing down. If you’re brand new to Connie Willis, fear not! A.M. Dellamonica is here to guide you through.

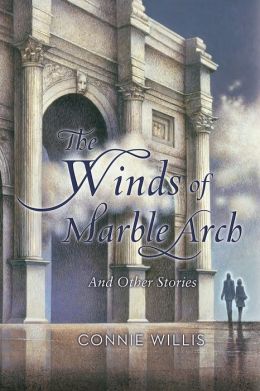

I started this essay by pulling out the compendium of Willis’ short fiction, The Winds of Marble Arch, with an eye to finding “Blued Moon.” My thought was that light, bubbly comedies are how I got started on Connie Willis, and they made a bright, lasting, and pleasant first impression. And hooray—it’s there—so I can recommend that same starting point to you!

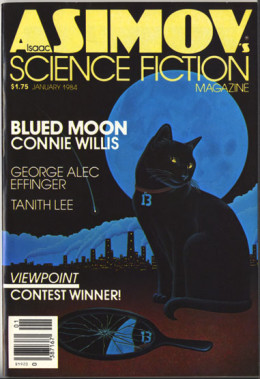

“Blued Moon” appeared in Asimov’s SF in January 1984. By then, its author had been selling SF stories for a half-dozen years, and her work was beginning to appear regularly in the better-known markets of the time. It’s about about linguistics and chaos theory and fads in language generation, with a romantic storyline which serves as the backbone for these ideas. It was nominated for a Hugo Award, just one short year after its author won her first, for “Fire Watch.”

“Blued Moon” appeared in Asimov’s SF in January 1984. By then, its author had been selling SF stories for a half-dozen years, and her work was beginning to appear regularly in the better-known markets of the time. It’s about about linguistics and chaos theory and fads in language generation, with a romantic storyline which serves as the backbone for these ideas. It was nominated for a Hugo Award, just one short year after its author won her first, for “Fire Watch.”

It’s also got at least one truly great pratfall.

If you are somehow coming to Willis with no experience whatsoever, then why not meet her as so many others did in the Eighties, with this zany and carefully constructed romp about humans who are busily and passionately engaged with misunderstanding science, the universe, and each other? (If you love it, and just want to extend the giggly part of the honeymoon indefinitely, don’t hesitate to go find Impossible Things, and “Spice Pogrom,” which is longer and just as delicious.)

I recommend the comedies in part because they are fun, of course, but also because if you don’t know Connie Willis already you might not know that she is a writer with immense artistic ambition. Her heroes include Shakespeare and Heinlein, Mark Twain and Dorothy Parker, Shirley Jackson and Charles Dickens… and one of the things she explicitly pursues as an artist is range. She wants to be nothing less than great both at writing laugh-out-loud comedy and searing, intimate, heartbreaking tragedy.

Imagine meeting somebody who’d got to their thirties and never really dipped into Shakespeare. Who would you recommend? If it was me, I’d never go with Macbeth or Othello. I’d pick As You Like It, or possibly Twelfth Night. I might even go with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, even though it’s not my personal favorite. They’re crowd-pleasing, the comedies. They let you see the author can do brilliant things, and while they’ll probably contain a few disturbing little undercurrents—because the best comedy always grows out of a seed of darkness—they’re not going say hello by ripping your still-beating heart out of your chest and throwing it to the first available pack of wolves.

Imagine meeting somebody who’d got to their thirties and never really dipped into Shakespeare. Who would you recommend? If it was me, I’d never go with Macbeth or Othello. I’d pick As You Like It, or possibly Twelfth Night. I might even go with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, even though it’s not my personal favorite. They’re crowd-pleasing, the comedies. They let you see the author can do brilliant things, and while they’ll probably contain a few disturbing little undercurrents—because the best comedy always grows out of a seed of darkness—they’re not going say hello by ripping your still-beating heart out of your chest and throwing it to the first available pack of wolves.

This brings up another thing, because it’s tempting to hear this as “Start with the easy stuff.”

On the contrary, I would argue that tragedy and carnage are easy to pull off, at least when compared to successful humor writing. Humor is, in fact, devilishly hard. Imagine a world where TV’s Game of Thrones was required by law or ridiculous circumstance to have one episode or storyline—one full hour of television per season out of the ten they give us—that was an unmitigated laugh riot. Would you want to be the one tasked with writing it, or would you rather beat up Theon some more?

So: comedy. It’s an icebreaker, an opportunity to show off, and—finally hewing back to the point—few SF writers do it better than Willis. So start with “Blued Moon.” You won’t be sorry.

So: comedy. It’s an icebreaker, an opportunity to show off, and—finally hewing back to the point—few SF writers do it better than Willis. So start with “Blued Moon.” You won’t be sorry.

What about moving on to the darker stuff?

That first Hugo and Nebula Award winner, “Fire Watch,” is where I’d go next. It is the beginning of the Oxford time travel sequence, a universe where Willis spends considerable time and energy, and it is about loss, mortality and, once again, misunderstandings. This is a theme you’ll see again and again in these works: Willis is very much about humans not only making the wrong assumption, but taking it to illogical extremes.

“Fire Watch” is the diary of a young historian who’s headed out on a field trip, an important core requirement for his degree. His mission: time travel to the past and observe the locals (or contemps, as they’re called). A clerical error sends him to the London Blitz, where he’s assigned to the fire watch for Saint Paul’s Cathedral. It’s not his chosen historical period; he was looking to hang out with Saint Paul. He’s unprepared and has no idea what’s going on, and in a rush he uses advanced learning technology to dump a bunch of facts about the 20th century into his long-term memory, hoping they might surface at a point where they can save him from being arrested for a traitor, or blown up by a German incendiary.

I’ve heard Willis say more than once that time travel is an inherently sad genre, because the traveler moves through a world that is already gone. Even if he or she saves the day somehow, preserving a human life or an architectural marvel, that victory is ephemeral. The Oxford historians return home knowing that everyone they met on their journeys—people who were real and vividly alive just the day before—has lived out their mortal span.

I’ve heard Willis say more than once that time travel is an inherently sad genre, because the traveler moves through a world that is already gone. Even if he or she saves the day somehow, preserving a human life or an architectural marvel, that victory is ephemeral. The Oxford historians return home knowing that everyone they met on their journeys—people who were real and vividly alive just the day before—has lived out their mortal span.

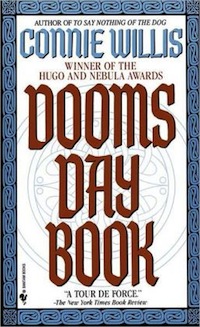

“Fire Watch” isn’t long, and when you’ve polished it off and are for more, I say jump right into Doomsday Book, the book that Jo Walton memorably calls “…the book where she got everything right.” This is a full-length novel, and the concept is exactly the same… but this time the young historian, Kivrin, is mistakenly sent to a time and place that makes surviving a Luftewaffe bombing seem about as hard as spending Thanksgiving with a mildly dysfunctional family.

The book is of academic interest, too, when set against “Fire Watch,” because Willis does more worldbuilding on that Oxford future, not to mention developing the time travel technology that lies at its heart. Oh, and if you’re keeping score? Doomsday Book isn’t one of the funny ones. It boasts, among other things, a truly impressive body count. Don’t blame the messenger, though; she’s just working with what history dished out.

What’s next? If you’d like a palate cleanser, here are a few more of the delightful stories you could dip into: “At the Rialto,” the politically sharp-edged “Ado” and “Even the Queen,” or perhaps her War of the Worlds Martians vs. Emily Dickinsen tie-in, “The Soul Selects Her Own Society” are especially great. Or, depending on when in the year you manage to get to this point, consider checking out the Christmas cheer in Miracle and Other Christmas Stories. (Mur Lafferty has written eloquently about that collection–go see!)

What’s next? If you’d like a palate cleanser, here are a few more of the delightful stories you could dip into: “At the Rialto,” the politically sharp-edged “Ado” and “Even the Queen,” or perhaps her War of the Worlds Martians vs. Emily Dickinsen tie-in, “The Soul Selects Her Own Society” are especially great. Or, depending on when in the year you manage to get to this point, consider checking out the Christmas cheer in Miracle and Other Christmas Stories. (Mur Lafferty has written eloquently about that collection–go see!)

Then, after you’ve caught your breath and dried your eyes, read the next time travel novel, To Say Nothing of the Dog, to see what happens when she takes the same universe and the characters you know (by now, quite well!) in a comic direction.

This essay is about getting to know the writing of Connie Willis from an imagined position of complete innocence. It’s so tempting for me to go on forever, poring through all the stories, trying to determine the most sparkly order for reading all of these incredible works. I want to figure out when a person should get to the rampaging sheep in Bellwether or grapple with the Titanic disaster and near-death experiences in the somewhat prickly Passage. Just because I haven’t mentioned Remake or “Last of the Winnebagos” or “A Letter from the Clearys” doesn’t mean I don’t love them.

At this point you should have a good idea though, of what I’m recommending you do: take the opportunity to read the heavy stuff and then the light, to go at the long books and then chase them with a few of the shorts.

At this point you should have a good idea though, of what I’m recommending you do: take the opportunity to read the heavy stuff and then the light, to go at the long books and then chase them with a few of the shorts.

So the last book I’m going to talk about, the one I think you should skip and then go back to, is Connie’s first: Lincoln’s Dreams.

Lincoln’s Dreams is a strange puzzle of a novel. It’s one of those things I reread often. Unlike a lot of Willis’s work, it is set in America, during an American war, and it has all the elements you will by this time have seen in abundance in her other works: a knowledgeable researcher in possession of not nearly enough information, missed messages, misunderstandings, and big problem in the form of a doctor who thinks he knows it all, when he’s really just blustering to cover his own incompetence. It’s the story of a woman, Annie, who is having strangely believable dreams about the US Civil War, and a guy, Jeff, who she asks to explain them. Are the dreams paranormal in origin or merely a side effect of prescription drugs? We never find out.

It’s interesting to go back to this first novel after having read some of Willis’ bravura later work, to see where she started and how strong a writer she already was. Like Doomsday Book, Lincoln’s Dreams is filled with death and tragedy. But where Doomsday Book is about plague, Lincoln’s Dreams is her first major attempt to grapple, close up, with the most human of the legendary four horsemen: war. The dead of this first novel are not the unfortunate victims of microorganisms. They’re not even the anonymous victims of aerial bombing. They die by bombardment, bullet and bayonet, not to mention a thousand other calamities wrought by their fellow humans. Poor Annie is dreaming a nightmare that countless people lived and died through, and all Jeff can do is bear witness.

It is also a novel that defies just about every formula you could name.

Like a lot of books written before the era of Google and the smartphone, Lincoln’s Dreams has come to seem a little dated. Its plot turns, occasionally, on the idea of lost messages and it is packed with answering machines. Still, the one-way nature of the messages Jeff and Richard (the doctor) leave each other is echoed by the strange one-way pipeline Annie has to the 1860s. They are all shouting messages into a void without knowing if they’re doing any good.

Like a lot of books written before the era of Google and the smartphone, Lincoln’s Dreams has come to seem a little dated. Its plot turns, occasionally, on the idea of lost messages and it is packed with answering machines. Still, the one-way nature of the messages Jeff and Richard (the doctor) leave each other is echoed by the strange one-way pipeline Annie has to the 1860s. They are all shouting messages into a void without knowing if they’re doing any good.

This little bit of dating is another reason I think Lincoln’s Dreams isn’t the place to necessarily start with the novels of Connie Willis. It’s a book that reminds us that we too are the contemps of all her time travel stories. The present day world of Lincoln’s Dreams is already our past, one that some of us are too young to remember. The novel is tethered to a time that’s receding, day by day, as the present always does. This is both inevitable and something of an irony for a book which is about the past’s disastrous choices, and the indelible stamp they leave, decades and even centuries later, on the present.

A.M. Dellamonica has a book’s worth of fiction up here on Tor.com, including the time travel horror story “The Color of Paradox.” There’s also “The Ugly Woman of Castello di Putti,” the second of a series of stories called The Gales. Both this story and its predecessor, “Among the Silvering Herd,” are prequels to her Tor novel, Child of a Hidden Sea.

If sailing ships, pirates, magic and international intrigue aren’t your thing, though, her ‘baby werewolf has two mommies’ story, “The Cage,” made the Locus Recommended Reading List for 2010. Or check out her sexy novelette, “Wild Things,” a tie-in to the world of her award winning novel Indigo Springs and its sequel, Blue Magic.

I absolutely love the Doomsday Book, but whenever I go back to it (or the others in the series) I feel jarred every single time that she refuses to include the concept of an answering machine, let alone a cellphone. It really is that bad to me. I do appreciate the historical portions that much more in comparison.

@1 That’s an unfortunate shortcoming of the time-travel novels, which I adore: Her future got old. She created her 2060 in 1983, and who knew in 1983 that email, text messaging, and smartphones were coming? And because she has a real sweet tooth for plots pushed forward by communications failures, it becomes kind of an issue. (I wrote a whole rant about this, even, when I was three chapters into Blackout. Fortunately, she provides a convenient “and this is why nobody ever sends text messages” continuity band-aid in I think Chapter 4.)

The lack of cell phones and even answering machines really dates her novels like The Doomsday Book because she hinges so many “modern” plot points on missed messages. I read The Doomsday Book in the mid-2000s and honestly thought the “modern” plot was set contemporaneously to when it was written (around mid-1980s, I thought) and was quite surprised to find out it was meant to be set in the future. She failed to predict and then proceeded to deny (once it happened) that everyone will carry a mobile device and be almost instantaneously reachable by 2010. This is honestly a big flaw that dates even her most recent work.

But, yes, she a good writer. I have enjoyed many a short story of hers and Bellweather, To Say Nothing of the Dog, and The Doomsday Book. I will make an effort to read some of her other works; although, I do plan to skip Blackout/All Clear because I object to splitting a single story among multiple books and it’s long.

Sorry, I’m not buying it. The Doomsday Book came out in 1992 – I know that’s the year that I first moved to a cellphone as my only line (a couple of years too early, but still), and answering machines had been boringly commonplace for at least a decade.

Even when Fire Watch was written a decade earlier (1982) answering machines were far from new technology and mobile communications had been a SciFi mainstay for decades. For a series set in the mid 21st century (2054 according to Wikipedia – I don’t have my copy handy) that still makes no sense.

Damn fine books otherwise, though.

Where is Blackout/All Clear? It’s a fantastic book, walking a careful balance between the humor of To Say Nothing of the Dog and the bleakness of The Doomsday Book. And yes, I’m calling it a singular “book” because it tells one story and was split by the publishers, not Willis.

Blackout was actually my first Connie Willis book. I found it at a second-hand bookstore in Israel. Just my luck the bookstore didn’t have All Clear, and I had to wait months to read it until I got back to the US.

I really loved Blackout and All clear when I read them a few years ago… IMHO the time travel element just added a bit of mystery to a really stellar description of life during WWII. I have never read any of her comedies I will have to check them out.

I would recommend skipping the title story in Bellwether, in which she lambasts anti-smoking laws as persecution and PC, instead of the matter of public health policy they really are. As someone whose cigarette-addicted mother gave her husband emphysema and refused to stop smoking even when her daughter was having daily asthma attacks, I have no sympathy with that position.

I’m rereading Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time for the first time in decades. What are kenners but smart phones? The similarities are striking.

As someone who has devoured everything Willis since 1979, I will say that her novels are not dated. If so – then great SF works like “The Space Merchants” and “Childhood’s End” are dated. No, they do not follow what really happened in our time, but to let such a thing bug you so much that it becomes a major problem is to miss the true timelessness of these stories and other classics of the field. Olaf Stapledon’s ‘Last and First Men” is incorrect in the specifics but it is a work of imagination that is just as valid today as it ever was. Willis’s novels – especially “Doomsday Book” and “Passage” are for the ages. No one 40 years hence will notice or care about the things that date them. They will be able to encompass a world that speaks deeply to all humanity – about communication, fear, death and deep, deep love. Ms. Willis , I have loved your work since “Daisy in the Sun” and have read all I can. I don’t like some of it, true, but I love so much that I am very, very pleased to have spent my time in your worlds. Thank you.

I am a huge fan of Connie Willis’ work. In my attempts to hook others, I typically bait the hook with “Miracle” (the story or the book collection), given at Christmas. This has worked more than once! “Are there any more like this?” I myself like best her funny short stories and her serious novels, especially Doomsday Book and Passage.

I feel I should mention Inside Job. A very clever and witty novella she published in 2005.

Strangely, the presence of answering machines in Lincoln’s Dreams makes it seem older, to me, than their absence in Doomsday Book. But your point (RJ, Andrew, and Fangirl) is a good one–the fact that these things are ubiquitous now makes them seem very obviously missing from these novels.

Miriam, I simply left out Blackout/All Clear because it’s nowhere near where I’d start with Willis. I think it’s cool that you did, though.

Mantelli, I have strong feelings about smokers, too. I do generally agree that as a society we judge and shame people for behaviors that are none of our business, but when I get a lungful of somebody else’s tobacco I tend to resent it, and them.

Sun Stealer, I completely agree that Inside Job is superfun.

Bob, I’d argue that Childhood’s End is dated. One for the ages, as you say, but no longer cutting edge. And I love your heartfelt thank you to CW.

Saavik, baiting people with Miracle is brilliant!

Count the days, people: I believe her newest will be out in January!!

Even when Fire Watch was written a decade earlier (1982) answering machines were far from new technology and mobile communications had been a SciFi mainstay for decades.

Indeed – for many decades.

“Oh, hey, your phone is sounding,” one of Matt Dawson’s fellow cadets points out to him while they’re standing in the airport, and he excuses himself, pulls the phone out of his pocket and answers it – Robert Heinlein’s Space Cadet, written in 1946!

Blackout/All Clear probably best not mentioned as IIRC that was the one that imposed college room-mates, decimal currency, garter snakes and other infelicities on the UK of the 1940s.

I enjoy Willis a ton but I got whiplash reading back to back Doomsday (whose essential point is that time travel involves life and death issues and can’t be taken lightly) and To Say Nothing of the Dog (whose principal plot kicks off when an exhausted time traveler is sent back to Victorian England without rest and without preparation or training in order to help obtain an elaborate piece of art). Both great books on their own (especially Doomsday, which gutted me) but too offputting when read together.

I’ve loved most of Connie Willis’s work over the years. Her short stories are brilliant, and I say this as someone who generally dislikes short stories (my favourite is “Even the Queen”). And I’ve found her last few books….lacking.

In “Passage” I got really tired of all the main character’s wandering around in that gigantic old hospital, and her every move had to be preceded by her conceiving a detailed mental map of where she wanted to go. I know it was a metaphor, but it got really old really quickly. And the overall story was so depressing, I wondered if she was writing this in response to the death of a close relative.

And in “Blackout/All Clear” I got really tired of all the missed connections. I can see her putting in a few to make her point, but it she ended up going to ridiculous lengths with this trope. She could have shortened the book to fit in one volume, and had a much tighter story.

And then she added in another trope that I loathe; characters keeping vital information from each other because they don’t want to worry their love ones. If everyone had just been honest with each other, they would have had a much better idea of what they were up against. They might even have showed some competence.

I will continue to read Ms. Willis’ work, because she is very good. But I sure hope her next book shows that she’s trying some new things, and retiring a few old ones.

I see Passage as an attempt to look at death from another angle, which is, again, ambitious. I have mixed feelings about whether it entirely comes off, and I do take your point.

A lot of Willis depends on context. I love her work but I’m not familiar with old movies or American history, so Remake and Lincoln’s Dreams are lost on me.

I totally get that, Margaret. I found myself moved to reacquaint myself with my (at the time shaky) U.S. Civil War history after reading Lincoln’s Dreams, and I watched a few of those old movies, too. A few of them were actually appalling–Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, for example.

I’m always blown away by how intense her approach to research is!

I came across this thread after finishing Passage and wondering where I’d recommend people should start with Connie Willis whose work I enjoy immensely, but have not had much success recommending to friends & family. The original article and subsequent comments are very helpful, so thank you all!

For me, The Domesday Book is so good, so well-executed and so devastating that I almost wish I hadn’t read Blackout and All Clear – much as I enjoyed them. TDB completely nails the enormous human & social impact of the Black Death and its power is somehow weakened by the re-use of the time-travel set-up – so I’ve been reluctant to read To Say Nothing of the Dog.

I take the points made here and in many reviews about Willis’ clunky technology and the frenetic pace, misunderstandings and crossed wires that complicate her characters’ lives. That all applies in Passage, yet I never lost the thread of the story (I just stopped trying to figure out the floor plan of that crazy hospital!) and it still packs a big emotional punch. And I suspect that Joanna & Maisie will, like Kivrin, prove impossible to forget.

To Say Nothing of the Dog is a different animal (sorry) than Doomsday Book; same universe, entirely different kind of focus and tone. Actually, thinking about it makes me want to reread it.

I have been feeling the itch to read Connie again…It has been a while…I wonder if anyone else has noticed how her characters have so much trouble getting from A to B? It amuses me but sometimes also drives me crazy….ie in wartime England people did manage to get around, but I thought the characters would never get from the country to London….There was one, sorry I forget the title, in which people had to navigate around inside a large rambling hospital….almost impossible….I wonder if Connie has a problem with getting around? It often exasperates me while reading her books….But otherwise I do love her odd and interesting stories…The new one coming sounds fascinating…

I’ve just read Doomsday book, my first foray into Willis’s work, and I loved it. As others have said, the lack of modern (or even late 20th century) phone technology is a little jarring, but I’m used to that from classic sci-fi so I kind of read around it.

I personally think the over-Catholicisation of future-England was more problematic. In reality, England has been only minority Catholic for hundreds of years (since shortly after Henry VIII had a wee falling out with the Pope), has been essentially secular with even ‘Church of England’ people being largely non-practising since the mid 20th century, and now in the early 21st century can make a decent claim to being majority atheist (e.g. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/23/no-religion-outnumber-christians-england-wales-study), despite having no constitutional principle of separation of church and state.

However, although it is highly unlikely that 2050s England would have become heavily Catholic (or even heavily ‘Christian’ in general terms), I think it was a sensible artistic choice as it made future-England a better mirror for mediaeval England. The (albeit more realistic) alternative would have been for us to have read about Kivrin undergoing a lot of training in Catholic belief and practice, and that would have been pretty boring – more of a ‘diary of a seminary’ than a ground-breaking, and heart-breaking, sci-fi journey.

I’ll definitely be reading more of Willis’s work – just not sure where (or when) to go next.

Doomsday Book was not my first Willis book – that was Blackout – but both of them had something in common for me – the need to skip ahead, speed-reading of a sort to gloss over the banal and the boring parts. Half of the home-base part of Doomsday could have been left out and I would have never missed it. The bell-ringers were boring me to death, when their unlikely ‘American’ childishness was not making me want to pass over the whole chapter. The mother of Willson was much the same – just a thorn in the side of the reader, a painful presence interfering with a normal effort to read the story. Then Dr. Ahrens death did not have much of any impact to me, though it should have. It could have been because the young kid called her Great Aunt Mary several times when trying to let known her death, rather than the Dr Ahrens name by which her close friend who knew and loved her during the whole first part of the book. If she had left out the many annoying references to lack of lavatory paper and the endless details of the fruitless search for the vacationing Balliol lab boss the book would have been much tighter. My last complaint about Doomsday is the presence of so much death – does everyone down to the precocious babe, her puppy, and the heroic priest have to die? Even the milk cow was left to suffer and possibly die with no one in the village left alive to milk her, the uptimers leaving her behind, bellowing in pain as her udder fills to bursting. I turn off TV shows the moment they begin beating up people, or start mistreating children or pets, or causing deaths which do nothing to advance the story line. Gratuitous violence fills Doomsday in more ways than one. But I could not turn off Doomsday, in spite of the quirks I disliked, and as for her short stories, they are gems, every one I have read. I recommend without reservation the short novel or novella Uncharted Territory, which has none of the quirks that I found less likable in Doomsday.

I found Connie Willis fairly early, IIRC, on the strength of a rave for Lincoln’s Dreams in the New York Times Book Review. It was one of the few books (Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow was another) that I closed with tears rolling down my face and immediately reopened to read again. Willis is a wonderful writer, and this is a great introduction.

I recently finished Blackiut All Clear. I have been a fan of Ms. Willis for many years. I think the first of her works I read was Doomsday Book, of all things, which totally destroyed me and which I have re read several times since with the same results. I don’t know why I never read Blackout All Clear when it first came out. I think it may be my favorite of her novels at this point. I love the fact that she mixes sadness as well as hope and even comedy in the story. ( it is a comedy, not a tragedy, yes?) I also loved seeing some returning characters and finding what happened in their futures. And her descriptions of life in England in WW2 were particularly affecting to me. Simply brilliant, and I can certainly see why it won all the awards it did.

I read three of Connie Willis’s books in the 80’s.

They all involved protagonist’s lives being made harder and more dangerous by someone with power, nominally on their side, acting out of malice and stupidity.

I won’t read Connie Willis for the same reason I won’t read Thomas Hardy.