“…I don’t think you know many Radchaai, not personally. Not well. You look at it from the outside, and you see conformity and brainwashing… But they are people, and they do have different opinions about things.” [Leckie, Ancillary Justice: 103]

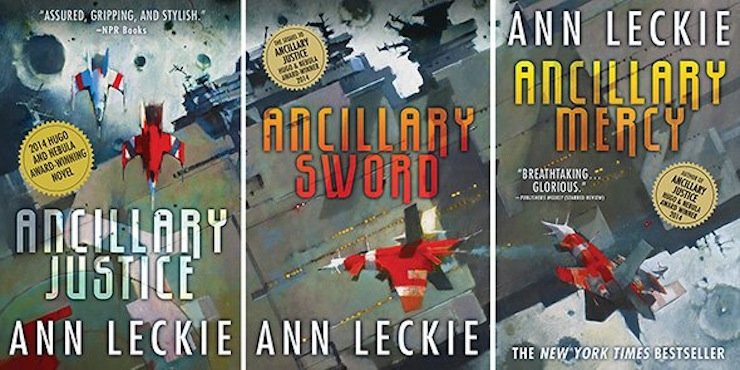

Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch books—the trilogy which comprises Ancillary Justice, Ancillary Sword, and Ancillary Mercy—have a significant amount of thematic depth. On the surface, this trilogy offers fairly straightforward space opera adventure: but underneath are a set of nested, interlocking conversations about justice and empire, identity and complicity. How one sees oneself versus how one is seen by others: when is a person a tool and when is a tool a person? The trilogy is one long argument on negotiating personhood and the appropriate uses of power; on civilisation and the other; and on who gets to draw which lines, and how.

It’s also, as I may have observed before, about what you do with what’s done to you.

This post assumes you have read the trilogy in question. Therefore there will be spoilers, and prior knowledge is taken for granted. With that said, let’s talk about Breq.

Breq, and Seivarden, and Tisarwat, and Anander Mianaai; Mercy of Kalr, and Sphene, and Athoek Station, and Translator Zeiat. But mostly Breq, for it is through Breq’s eyes that we see the world of the narrative. (Breq is an unreliable narrator, in a charmingly subtle way: in many ways extremely perceptive, but not where it comes to her own emotional states. Leckie’s narrative deliberately understates her emotional responses, so the disjoint between what Breq tells us and what the reactions of people around her tells us is a distinct and noticeable thing.) Breq has occupied—does occupy—many roles: she remembers being the troopship Justice of Toren, of which she is the last remaining fragment. She is a lone ancillary, and she insists on her identity as Justice of Toren. She might not be what she was, but she is still a ship. In the Radch, a ship is not a person, not a she but an it: a tool, not a citizen.

But Breq is other things as well.

Breq, over the course of the first book, is seen by various different people as a representative of the Radch, as a tool of the Radch, as a foreigner within the Radch (when she arrives at Omaugh Palace), and as an aberration: a tool gone mad and self-willed. In Ancillary Justice, Justice of Toren has very little power except as the tool of others’ wills, and Breq is an outsider. A wealthy outsider, and one who is intimately familiar with the culture and assumptions of the society in which she is moving—the society at whose leader she intends to strike—but still, not a citizen. Not Radchaai; not civilised.

In Ancillary Sword, though, Breq has been given the name Mianaai (against her will), a name which signifies to others that she belongs to a Radchaai elite. She has the title Fleet Captain, a position which literally gives her the power of life and death over those assigned to her command, and in some degree beyond it; she has command of the ship Mercy of Kalr and is the senior officer in the Athoek system—which makes her one of the most powerful political actors in the Athoek system, if not the most powerful. Vanishingly few people know that she is an ancillary, that she was (is) Justice of Toren: no one looks at her and sees an outsider.

“You are so civilised,” says one (not Radchaai) inhabitant of Athoek to Breq:

“So polite. So brave coming here alone when you know no one here would dare touch you. So easy to be all those things, when all the power is on your side.”

and goes on to accuse her:

“You’re the just one, the kind one, are you? But you’re no different from the daughter of the house… All of you! You take what you want at the end of a gun, you murder and rape and steal, and you call it bringing civilisation. And what is civilisation, to you, but us being properly grateful to be murdered and raped and stolen from? You said you knew justice when you heard it. Well, what is your justice but you allowed to treat us as you like, and us condemned for even attempting to defend ourselves?”

To which Breq makes the answer: What you say is true.

(There are ways in which the novel’s examination of neurological identity—in the case of Breq, and especially of Tisarwat—parallels its examination of cultural identity and imperialism. But I think I will get to that later.)

In Ancillary Mercy, the lines between Breq-as-outsider and Breq-as-Fleet-Captain—other and aberrant vs. powerful and prestigious—are breached: her human crew is now aware of her nature as the last remaining part of Justice of Toren, by her own choice, and her identity as an ancillary soldier (as an it, a thing, a tool) is revealed to the inhabitants of Athoek system by Anander Mianaai in order to deprive Breq of her allies. Yet Breq has not made allies—won loyalties—because of her position, but because of how she used that position: because of what she does with who she is. (The result within the narrative of Anander Mianaai’s revelation is rather less to deprive Breq of allies and rather more to destabilise the local norm around the perception of AIs—if someone who they’ve seen as a person was once a tool, then perhaps the tools around them are also people—thus laying the groundwork for the trilogy’s denouement to be both believable and satisfying.)

Breq’s arc through the trilogy involves negotiating with power from the perspective of someone who understands what it is to be utterly subject to another’s will, and who is then given the power to subject others to their own will—and who acknowledges the difficulties, the moral greyness, inherent in the responsible use of power. Breq never tries to excuse her own participation in and complicity with imperial violence, past or present. She doesn’t justify it, though she is able to see and articulate how other people justify it:

“…Imagine your whole life aimed at conquest, at the spread of Radchaai space. You see murder and destruction on an unimaginable scale, but they see the spread of civilisation, of Justice and Propriety, of Benefit for the universe. The death and destruction, these are unavoidable by-products of this one, supreme good.”

“I don’t think I can muster much sympathy for their perspective.”

“I don’t ask it. Only stand there a moment, and look. Not only your life, but the lives of all your house, and your ancestors for a thousand years or more before you, are invested in this idea, these actions. Amaat wills it. God wills it, the universe itself wills all this. And then one day someone tells you maybe you were mistaken. And your life won’t be what you imagined it to be.”

[Leckie, Ancillary Justice: 103]

And she is remarkably clear-sighted about its costs and effects, and throughout the text, is at pains to work respectfully around people where the hierarchy of power puts her at a distinct advantage. (Although Breq is not always successful at this, because of the very nature of power.)

Compare—contrast!—Seivarden Vendaai, the only character bar Breq herself (and Anander Mianaai) who has a presence across all three books of the trilogy. Seivarden, who was born near the pinnacle of the Radchaai hierarchy of power, who was Captain of her own ship—until she loses that ship and a thousand years, to boot, and wakes up in a Radch that’s just familiar enough to make its strangenesses all the more jarring. We meet Seivarden as an addict face-down in the snow of a planet beyond the Radch’s borders, unlikeable and self-absorbed, inclined to self-pity and unwilling to ask for help, but still sufficiently convinced of her own importance that she assumes Breq is on a mission to bring her back to the Radch. (Seivarden has never understood what it means to be powerless.) Seivarden has all the flaws of her context, as Breq points out quite mercilessly:

“She was born surrounded by wealth and privilege. She thinks she’s learned to question that. But she hasn’t learned quite as much as she thinks she has, and having that pointed out to her, well, she doesn’t react well to it.” [Leckie, Ancillary Mercy: 130]

And to Seivarden herself:

“You have always expected anyone beneath you to be careful of your emotional needs. You are even now hoping I will say something to make you feel better.” [Leckie Ancillary Mercy: 176]

She has her virtues, as well—her unshakeable loyalty, her stubbornness, her growing resolve to learn to do better, and her willingness to try her best with what she’s got—but in many ways in Seivarden we see someone who once had all the power that Breq is given in Ancillary Mercy: had it, and considered it hers by right, with the kind of thoughtless arrogance that saw the way things were as the way the universe was supposed to be.

Through the gradual abrading-away of Seivarden’s arrogance (slowly replaced with slightly better understanding), the narrative gives us an argument about how taking power for granted imposes a narrowness of vision, an empathy that only ever goes one way. Seivarden-as-she-was and Seivarden-as-she-becomes are mirrored in the two competing factions of Anander Mianaai—though I think Breq’s influence has made Seivarden more open to seeing other points of view than even the less imperialist version of the tyrant, by the end of Ancillary Mercy.

I may also identify just a little too much with Seivarden—for any number of reasons.

Mercy of Kalr was crewed by humans. But its last captain had demanded those humans behave as much like ancillaries as possible. Even when her own Kalrs had addressed her, they had done so in the way Ship might have. As though they had no personal concerns or desires. [Leckie Ancillary Sword: 57]

“I can bring you back. I’m sure I can.”

“You can kill me, you mean. You can destroy my sense of self and replace it with one you approve of.”

[Leckie Ancillary Justice: 135]

Captain Vel didn’t want her crew to be people, but tools: wanted to see them as part of the ship—even as Mercy of Kalr missed its ancillary bodies, now lost to it forever. The doctor Strigan sees Breq’s ancillary body as a victim, rejects its identity as Justice of Toren, as Breq, even as Breq insists on the integrity of her identity as an AI.

“I wanted to ask you, Fleet Captain. Back at Omaugh, you said I could be my own captain. Did you mean that?”

[…]

“…I’ve concluded I don’t want to be a captain. But I find I like the thought that I could be.”

[Leckie Ancillary Mercy: 6]

And Breq finds herself unexpectedly startled by what she herself had taken for granted, in the case of Mercy of Kalr: the realisation that she too has been thinking of the ship more as a tool than as a being with will and desires of its own. She, Justice of Toren, who should know better.

From a certain angle, the Ancillary trilogy—and certainly Ancillary Mercy—is about the permeability of categories taken to be separate, and about the mutability, and yes the permeability too, of identities. Mercy of Kalr has no ancillaries anymore, but it (she) begins to use her human crew to speak through as though they were ancillaries—but not against their will. Breq is both AI and Fleet Captain, Radchaai and not, simultaneously a colonised body and a colonising one. Tisarwat—whose identity was literally remade during Ancillary Sword, both times without her consent—uses what that remaking has done to her to give Athoek Station and a number of ships a choice in what orders they follow: she allows them to be more than tools with feelings. Seivarden—learning how to live with who she is now—is wrestling with her own demons; Lieutenant Ekalu—a soldier promoted from the ranks to officer, a previously-uncrossable barrier crossed—with hers. Athoek Station and Mercy of Kalr and Sphene make laughable the Radchaai linguistic distinction between it-the-AI and she-the-person. (And numerous characters draw attention to the Radchaai linguistic quirk that makes the word Radch the same as the word for civilisation, while quite thoroughly demonstrating that Radchaai and civilised are only the same thing from a certain point of view.)

And there is a whole other essay to be written on the arguments about category and identity and Anander Mianaai. To say nothing of Translator Zeiat and her predecessor Translator Dlique.

It is Translator Zeiat, in fact, whose words draw explicit attention to the permeability of categories, and of the arbitrary nature of the lines that divide them—the arbitrary nature of civilised Radchaai set theory. Zeiat, as a Presger Translator, is deeply peculiar: the Presger are quite literally unknowably alien. And Zeiat also frequently adds much absurdist humour to Ancillary Mercy, so it’s easy at first to dismiss her contribution as more wackiness that serves only to demonstrate just how alien the Presger are. But look:

[Translator Zeiat] took the tray of cakes off the counter, set it in the middle of the table. “These are cakes.”

[…]

…”All of them! All cakes!” Completely delighted at the thought. She swept the cakes off the tray and onto the table, and made two piles of them. “Now these,” she said, indicating the slightly larger stack of cinnamon date cakes, “have fruit in them. And these”—she indicated the others—”do not. Do you see? They were the same before, but now they’re different. And look. You might think to yourself—I know I thought it to myself—that they’re different because of the fruit. Or the not-fruit, you know, as the case may be. But watch this!” She took the stacks apart, set the cakes in haphazard ranks. “Now I make a line. I just imagine one!” She leaned over, put her arm in the middle of the rows of cakes, and swept some of them to one side. “Now these,” she pointed at one side, “are different from these.” She pointed to the others. “But some of them have fruit and some don’t. They were different before, but now they’re the same. And the other side of the line, likewise. And now.” She reached over and took a counter from the game board.

“No cheating, Translator,” said Sphene. Calm and pleasant.

“I’ll put it back,” Translator Zeiat protested, and then set the counter down among the cakes. “They were different—you accept, don’t you, that they were different before?—but now they’re the same.”

“I suspect the counter doesn’t taste quite as good as the cakes,” said Sphene.

“That would be a matter of opinion,” Translator Zeiat said, just the smallest bit primly. “Besides, it is a cake now.” She frowned. “Or are the cakes counters now?”

“I don’t think so, Translator,” I said. “Not either way.” Carefully I stood up from my chair.

“Ah, Fleet Captain, that’s because you can’t see my imaginary line. But it’s real.” She tapped her forehead. “It exists.” She took one of the date cakes, and set it on the game board where the counter had been. “See, I told you I’d put it back.”

[Leckie Ancillary Mercy: 207-208]

Now that’s a fantastically pointed piece of writing, in any number of ways. Once you take it out and examine it, it almost feels a little too on the nose. But here, I think, we have an explicit formulation of (one of) Leckie’s thematic arguments: that the line between person and tool, civilised and uncivilised, is simultaneously imaginary and real. That where that line falls is a social agreement, which can be enforced through both subtle and brutal kinds of violence.

Arbitrary lines are never just. And I find it significant that Breq is Justice of Toren: that amidst its thematic discussions of identity and power, there’s an underlying if unstated argument about justice.

And benefit, and propriety. But mostly justice.

It’s a satisfying narrative irony, though, that Ancillary Mercy’s conclusion—the liberation of Athoek system from the Radch of Anander Mianaai and its semantic reconstitution as part of the “Republic of the Two Systems”—is made possible only by appeal to the arbitrary-in-human-terms and unknowable Presger. Breq might be trying in her own way to disentangle Athoek system from imperialist modes of discourse and operation, but her gambit can only succeed because the Presger have a much bigger stick than Anander Mianaai.

Is it just and fair, what Breq does? Not exactly. But imperfect justice in an imperfect world is, in the sum of things, better than no justice at all.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She has recently completed a doctoral dissertation in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter. She would like to acknowledge the debt this essay owes to numerous conversations on the Radch with Fade Manley.

I love this whole topic, and I’m going to be chewing over it for a while. Divisions, and how arbitrary they are, and how important they are, because just as with money and gender and culture, being arbitrary and based merely on how humans view things doesn’t make them not real. Just…arbitrary. And very much based on who gets to make the rule.

Another example from the book that comes to mind: the small child in the flashback sequence of the first book, who teaches Justice of Toren One Esk a song for candy, returns with a flower offering later, and sees Anaander there. She is so very clearly an Other on every level but the legal one at that point: she’s not only from a recently conquered planet, but from a less privileged part of the local culture. And yet she is, officially and legally, part of the Radch Empire, a citizen in full with all the rights attendant. At least in theory.

She’s such a citizen, in fact, that when we next see her in the books, she’s the client of a quite wealthy patron, and has a respectable government job. She’s dressed like all the people around her. She has local friends. She can walk into the good tea shops, that would be a bit suspicious of foreigners, as if she belongs. And Seivarden can still look at her and call her “provincial”, because even with all the legal categorization and explicit rights that have come along, this woman still doesn’t look quite Radch enough to someone from the top parts of society.

Arbitrary categories. Amorphous categories. Ones where what category you belong to shifts depending on who has the power when they look at you, or decide what happens next. It’s a theme all through the book, in metaphor and plot point and just as a quiet, constant issue.

“Breq as unreliable narrator…”

Yes, this unlocks a lot of the thematic depths of the novels. So often she seems clueless or unperceiving of the emotions and motivations of those around her. Then at other times she is more perceptive than those under her authority, which Leckie sometimes accomplishes by withholding Breq’s thought processes. Then there’s a payoff that shows Breq’s deeper understanding of a situation. Sometimes this is a result of her status of outsider, which is also a source of her sense of justice. Her travels outside the Radch and collecting songs from other cultures give her a perspective on colonial and imperial injustice that the locals can’t have. Apparently there’s no Galactic Library or university system that teaches these things, or it’s history likely suppressed by the Tyrant.

While the series was enjoyable, each book brought diminishing returns. Perhaps that was due to my expectations, partly fed by Leckie’s references to places and events off-stage, some of which became non-factors (like the build-up of the ghost gate, which became a simple hiding place). The narrative scope narrowed considerably from the first novel to the second. Breq went from “trekking” across the galaxy (even suggesting she became a sort of goddess in a non-Radch civilization – a story hopefully told someday) to settling down on Deep Space 9. Which is fine (I like DS9), but the second novel’s references to races and ethnicities (some only exiting as names with little background) that were abused by the locals became a bit muddled for me. We only meet one resentful character representing them, which is a lot of weight to bear.

Then there’s the collapsing of gender into “she” for everyone, including the alien translators. This can tie in to Breq’s cluelessness, as well as the Radch’s “gender blindness.” But consider how much richer the theme of entitlement becomes if we see Seivarden as male (he is described as physically male by the doctor who treats him in the first novel). One example is his condescending behavior to Lt Ekalu, his lover, which essentially amounts to a pat on the head when she does well, as in ”Good job… for a girl.”

Or consider the “daughter” of the plantation owner, who is a gay male abusing one of the trapped workers (serfs/slaves?). The young victim’s sister refers to both parties as “he.” Perhaps the sexuality involved is irrelevant to the crime, but a layer of meaning is still lost. Breq is sensitive enough to get the injustice, but perhaps on a theoretical level.

So instead of gender plurality, or multiplicity, we get a reduced sense of who theses characters are as people. There are hints here and there, such as when Breq arrives on the Station in the first novel. The description of the mass of people on the concourse is evocative of a exotic bird house. The body types and gender fluidity is amazing. Calling them all “she” is reductionist. A truly gender neutral term would have served better. After awhile I defaulted to seeing the story as (nearly) populated only by women. Nothing wrong with that (there’s precedent in SF by Joanna Russ and others), but may not have been what Leckie intended.

Should be interesting to see what the TV show (when/if it arrives) does with the gender (and racial) issues when the casting and visual elements define these characters more.

Sunspear, I see absolutely no evidence that “the “daughter” of the plantation owner…is a gay male abusing one of the trapped workers”. Is she abusing one of the workers? Yes. Is the worker in question male? Yes. But the Radch don’t have gender division, and we don’t know what kind of genitals the daughter in question has, either.

The things you call out as making the setting more nuanced and rich read to me as making it full of cliche and tired old tropes. Seivarden has no gender, and is referred to as she by everyone in her culture: there’s no reason to assume that her body parts make her condescending in a different way than Breq’s body’s parts do. We haven’t been given a “reduced sense” of these people, but freed from the relentless association of certain genders or body types with certain personality characteristics.

If I want to read “gay men are abusing sad boys!” I can look at alarmist articles from homophobic publications. If I want to read “Well, men are just naturally condescending and confident!” I can read MRA blogs. Why in the world would I want a science fiction novel set in a different culture and time period to adhere to the gender-essentialist assumptions of modern America?

This is a really thoughtful analysis of the trilogy!

@@@@@ 2: I don’t believe that the theme of entitlement would be richer were Seivarden presented as male. Because it’s not anatomy itself that instils some people with a sense of entitlement, but rather the meaning that a society assigns to that anatomy and the culture of how those with that anatomy are expected / allowed to behaviour.

Seviarden’s culture doesn’t care about her genitalia and she doesn’t identify as male, so her sense of entitlement arises from other things – her class status (and perhaps also her facial appearance as that seems to be a marker of her class status). I think that allows the narrative to comment on entitlement in a much broader way than if it only focused on entitlement in the context of gender. We’re still able to make comparisons between Seivarden and male entitlement as it exists in our society, but we’re not limited to interpreting Seivarden’s character as a commentary only on that.

Also, by tying Seivarden’s entitlement to class it may be easier to examine the way entitlement is socially constructed.

Something I appreciated about the use of she rather than a gender neutral term was that it stopped me from automatically – and unconsciously – assuming that all people with military titles were male. Because I kept doing that, I discovered. A gender neutral term wouldn’t have jarred enough with my assumptions to really challenge them or even to make me aware of their existence.

In a way, the use of she actually fits in with the trilogy’s commentary about arbitrary lines and the social agreements that make them real. Leckie has moved a line (between he/she), and does so in a way that highlights that this is another line that can be moved… provided there are the necessary social agreements to support it.

Breq always sounds like Clayton Moore to me: “I think not, citizen!!” The Masked Whatever, the Lone Ranger. That’s why I adore her. I also want to know how she became a goddess.

@Sunspear:

even suggesting she became a sort of goddess in a non-Radch civilization – a story hopefully told someday

In case you’re unaware, that story has already been told. Link to part one here. It’s pretty excellent.

@2 Sunspear – “Calling them all “she” is reductionist.”

That’s a fair point, but it’s not a fair point to raise against the novels or the author who wrote them; rather, it is a point against the culture in the novels and the characters who have been raised within it. And that’s something that the author does very deliberately. The linguistic trappings and limitations of the Radch are part of what makes them who they are and part of what Leckie is examining. And, well, that’s what the essay we’re commenting on also specifically examines. Is your contention that Leckie should have had entirely different narrative and thematic goals than she did?

@3: “but the Radch don’t have gender division…”

You may not be reading closely enough. As I said, outsiders to the Radch, like the doctor in the first novel or the plantation workers, easily identify body types and gender cues. They see Radchaai as looking at a spectrum and insisting there’s only one color.

The Radch is a deeply flawed and morally compromised empire. The overall critique of its imperialism and destructive colonization of other cultures shows how harmful their civilization can be. I could even argue that the gender “blindness” is a survival mechanism instituted by the Tyrant, since she/he can inhabit or absorb any body into the gestalt. Early in the first novel, during the occupation, the local Anander is described as an older black male. Later on the station, Anander is a young girl. It’s in his/her self-interest to not have the physical differences between bodies to be perceived (even though they are noted), leading to questioning of authority. A cultural norm set up by a imperial ruler, a unique hive-mind being, should be questioned and analyzed, not selectively taken at face value. This is what Breq figures out: subvert the control set up millennia earlier and start to break down this schizophrenic multiple being and the unjust twisted society he/she set up. Ironically, the AIs, Breq first, gain more individuality than most of the Radch. Some of the Radchaai most closely influenced by Breq become emotional wrecks by the third novel as they experience personal growth, a few held together by drugs. Individuation in this empire is hard and traumatic. (The mental health component of Tisarwat’s identity being forcibly violated twice could be an essay by itself.)

In the real world, I’m for gender and sexual fluidity, but I don’t think Leckie solved how to portray it in text form. Because of the limited visual cues, the use of the term “she” to apply to everyone increasingly felt like obfuscation and an opportunity to portray diversity missed. Breq is in an interesting situation because her status as both outsider and insider give her insight into the grievances of those wronged by the empire.

Edit: @6 Thank you much for the link.

@@@@@ Rick Sullivan: was working on my post before I saw yours. I agree with you that the depiction of the Radch has implicit critique built in, which is why it seems strange to pick and choose a “positive.” For me, the Radch reads like a Maoist conformist dictatorship.

Sunspear@8 – “Early in the first novel, during the occupation, the local Anaander is described as an older black male. Later on the station, Anaander is a young girl.”

Are you sure that the younger Anaander was actually female?

@9 Sunspear -“I agree with you that the depiction of the Radch has implicit critique built in, which is why it seems strange to pick and choose a “positive.””

I just re-read the essay and the comments, and I have no idea what you mean by this. Could you elaborate?

@11: As you said, Leckie “deliberately” built in the “linguistic trappings” of the Radch culture. As in any ideology, language can limit what a person on the inside can perceive or understand. Outsiders to the Radch have no trouble seeing distinctions that Radchaai cannot.

The day before annexation of a new planet: mothers, fathers, sons, daughters; perhaps third and fourth sexes with trans states as well. The day after annexation: all are mothers and daughters. We can’t be sure Radchaai are human. There’s a reference in the first novel to a long lost planet a lot like Earth, but not necessarily an ancestor planet.

So maybe they reproduce asexually, budding off daughters (which justifies the use of the term “daughter” for all offspring). Maybe they lay eggs or clone themselves. We don’t really know much from the novels. The non-Radch subject races, like the plantation workers seem to have no problem distinguishing such things. Maybe they see the Radch as culturally deluded or brainwashed. It is an empire led by a being who has been mentally ill for at least a thousand years, one willing to kill many thousands to hide that fact.

The flattening effect of using mother and daughter for everyone is an artifact of Radchaai language and culture that some readers take at face value as a positive thing. I see it as forced conformity that limits diversity and individuality.

As a side note, I don’t recall any two parent Radch households in the novels. Are they all single parents?

@10 Relativelly sure, though I’m not prepared to comb thru the text again to see why I formed that impression. The Omaugh Anaander was described as a small, feminine figure. I could be wrong.

Just because the *language* doesn’t have gendered pronouns (like many languages right here on Earth) doesn’t mean the *people* don’t have gender.

@12 Sunspear – “As you said, Leckie “deliberately” built in the “linguistic trappings” of the Radch culture. As in any ideology, language can limit what a person on the inside can perceive or understand. Outsiders to the Radch have no trouble seeing distinctions that Radchaai cannot.”

Yes, that’s one of Leckie’s points, one that we see Breq taking some time to realize as part of that character’s journey. Part of the point of the novels, and of this essay discussing aspects of those novels.

“The flattening effect of using mother and daughter for everyone is an artifact of Radchaai language and culture that some readers take at face value as a positive thing. I see it as forced conformity that limits diversity and individuality.”

Really? What readers see it as a positive thing? Certainly neither the author of this essay nor the other commenters have indicated that they see it that way. Instead they seem to see it as you describe after your final comma, and further see it as something that the readers are intended to see that way after they realize what is going on linguistically. That’s one of the things the essay we are commenting on is discussing. If someone is having a conversation where the Radchaai language constraints, along with its psychological effects, is being held up as something that is positive in and of itself, that conversation is simply not happening here. Yet you are arguing as if it is, which is rather mystifying.

I loved this analysis! Zeit was my favourite part of Ancillary Mercy and I would *love* a book told from the perspective of the Presger translators. I loved the layering of these books, within each one and each one with each other. It’s exquisite and I am already looking forward to doing a re-read of them all together at some stage.

@14: defaulting to the feminine to refer to a non-gendered norm has been discussed for several years now, going back to the publication of the first novel. The author herself describes her process in making that decision and generally presents it as positive choice, while acknowledging the drawbacks and that serves as counter-balance for our cultural default to the masculine:

http://www.orbitbooks.net/2013/10/01/said-said/

Here’s an example of a Tor.com reviewer who enjoyed the books, but found the use of a gendered pronoun to portray a non-gendered society frustrating:

http://www.tor.com/2014/02/18/post-binary-gender-in-sf-ancillary-justice-by-ann-leckie/

You can likely find many examples where “Radchaai language constraints” are interpreted as relief from ” the gender-essentialist assumptions of modern America” (commenter #3 above). Some of the commenters on the Feb 2014 article fully support Leckie’s choice, without due critique of the society that spawned the norms.

I’ve thought and talked about these issues for a couple years on other blogs. You and I seem to be close in our assessment of Leckie’s level of success in her linguistic choices. Considering the complex discussions going on these days about gender, Leckie’s portrayal seems limited and collapsed into one gender. We can blame this on the in-text cultural constraints of the Radch, but on the authorial/meta level, Leckie gives it some support (in her article).

So I may be confuzzled because the presentation of gender issues and ideas seem to be in conflict with themselves.

@16 – Sunspear – “defaulting to the feminine to refer to a non-gendered norm has been discussed for several years now, going back to the publication of the first novel.”

Yes, that has been discussed, in exactly the way that writers and readers discuss the writing process and results. Nothing controversial there…

“The author herself describes her process in making that decision and generally presents it as positive choice,”

Wait. Wait. Wait. The problem you are having here is *not*, as you previously seemed to indicate, seeing the Radchaai imposition of flattened identity as a problem, but the mere fact of choosing to describe such a culture at all and using this unusual narrative approach to do so? In science fiction? Where that sort of thing at least sometimes happens to varying degrees?

“while acknowledging the drawbacks and that serves as counter-balance for our cultural default to the masculine:””

Yes, she acknowledges the drawbacks. She was attempting to do something difficult and unusual, as part of crafting and depicting a civilization that was itself difficult and unusual. In science fiction. Where that sort of thing at least sometimes happens to varying degrees. In the article you link she describes how her solution created different writing challenges for her, and how all of that was what made it a “positive” for her. If this is a problem, an example of the author somehow being “wrong” to do what she did, perhaps you could explain it?

“Here’s an example of a Tor.com reviewer who enjoyed the books, but found the use of a gendered pronoun to portray a non-gendered society frustrating:”

Yes, some people did find it frustrating. And? Many others did not, and the books were generally well-received critically and sold pretty well.

“You can likely find many examples where “Radchaai language constraints” are interpreted as relief from ” the gender-essentialist assumptions of modern America” (commenter #3 above).”

Seriously?? Let’s take a look at the full statement from @fadeaccompli – “Why in the world would I want a science fiction novel set in a different culture and time period to adhere to the gender-essentialist assumptions of modern America?” What she’s applauding here is a choice of narrative style that reflects the thought processes of a person from a time and culture that is radically different from our own. In science fiction. Where that sort of thing happens to varying degrees.

“Some of the commenters on the Feb 2014 article fully support Leckie’s choice, without due critique of the society that spawned the norms.”

So what? And what would constitute “due critique” and why would it matter? If you are referring to the norms of the fictional Radchaai, then as you yourself noted the critique is baked into the novels and the viewpoint character’s narrative voice. If you mean contemporary America, there’s already plenty of existing critique; commenters can reference it or not as they choose, but I don’t see why they need to re-invent the wheel in order to somehow justify their comments.

“You and I seem to be close in our assessment of Leckie’s level of success in her linguistic choices.“

No, we don’t You are strongly disapproving, where I found it an interesting experiment that became more successful as the novels advanced. I found it unusual, because it is, but I managed to deal with LeGuin’s The Left Hand Of Darkness decades back, so I rolled with Leckie’s similar-but-different approach in her trilogy.

“Considering the complex discussions going on these days about gender, Leckie’s portrayal seems limited and collapsed into one gender.”

No. Leckie’s portrayal seems to reflect the thought processes of a character who lived her whole life in a civilization that imposes a limited and collapsed view of gender. Because it does. And that particular approach makes for a potentially interesting angle on the complex discussions going on these days about gender. That is obviously a different approach than attempting to shoulder all of the possible complexities of such a discussion herself, but that doesn’t make it bad or wrong or insufficient or a failure. It might if Leckie had ambitions to make the Ancillary trilogy a definitive philosophical tome on such issues, but she didn’t. In the link you provided she talks about the Radchaai linguistic perception of gender as one element of that universe. That’s it. And one that provided her with an interesting angle on gender and an interesting writing challenge. As part of what she was crafting. In science fiction. Where that sort of thing at least sometimes happens to varying degrees. Since you read the linked article you clearly already know this.

“We can blame this on the in-text cultural constraints of the Radch, but on the authorial/meta level, Leckie gives it some support (in her article).”

As. Part. Of. Her. Writing. Process. And construction of an alien culture. In science fiction. Where that sort of thing at least sometimes happens to varying degrees. As she said in the article you refer to. Is this what you object to, or is this what escapes you?

“So I may be confuzzled because the presentation of gender issues and ideas seem to be in conflict with themselves.”

Or there may be another reason.

I am just speaking for myself as an English speaking individual.

I liked that use of “she” as the default. I felt it pull at me with all the strength of born and raised cultural assumption. It made me uncomfortable and I found myself searching for clues as to what gender a “person” was in the story. Even Breq, who was not a “person” inside had a body that must have told her which gender she was in a physical sense. She didn’t care because it meant nothing to her but I did.

I think it’s in the first novel that Breq mentions she has difficulty in making gender distinctions not due to language but because the physical differences in clothed individuals don’t stand out to her.

The cakes-and-counters demonstration is thorough, isn’t it?

I sometimes sum up the lesson of a liberal arts education as: socially constructed things are real, too. (And, by the way, you are not immune, no matter how smart you are, and it’s not like Rumpelstiltskin, where once you’ve named the thing it has no power over you. And consequently, socially constructed things are worth studying and working on and fixing and spending energy on.)

People who appreciated the critique of class and empire in the Ancillary trilogy might also be interested in the fourth and fifth books in Mary Robinette Kowal’s Glamourist series, Valour and Vanity & Of Noble Family, though to get the whole effect I’d recommend reading the whole series in order. Our characters start off, in book one, experiencing artistic aristocratic lives in the quiet heart of the British Empire. And then in books 4 and 5 we get some incisive thoughts about the labour that the empire is based on.

I knew before reading this essay that I would at some point do a re-read of the entire trilogy. Now my re-read will be deeper and more interesting, informed by this fine analysis. Thanks, Liz Bourke!

@@.-@ Herenya–also well said, I agree entirely.

@17: “Leckie’s portrayal seems to reflect the thought processes of a character who lived her whole life in a civilization that imposes a limited and collapsed view of gender. Because it does. And that particular approach makes for a potentially interesting angle on the complex discussions going on these days about gender. That is obviously a different approach than attempting to shoulder all of the possible complexities of such a discussion herself, but that doesn’t make it bad or wrong or insufficient or a failure.”

We are literally talking past each other, which at least demonstrates how limited language is at communication. You also seem to be reading something into my statements (“Or there may be another reason”), as if I have an agenda of some kind.

So let me be more specific or explicit. Ideologically, I’m left of center; I thought the Sad and Rabid Puppies were ridiculous in their attempts to roll back diversity in awards representation; and I happen to think that Leckie’s writing is inadequate in context of the current discussion on gender fluidity and plurality. As the writer of the 2014 Tor.com article said, “It feels dated.” And that was before the world met Caitlyn Jenner.

You keep hammering home that we are dealing with an alien culture, in science fiction (in a condescending way), which should usually indicate that it extrapolates from our current society to give us a more advanced view or examination of the subjects and issues presented. However, we get less complexity than the discussion we are having here today, on planet Earth. It may have been “difficult and unusual” to “varying degrees” for the author personally, as you said, but I think Le Guin came far closer to building a true genderless society, despite the use of the default “he.”

Say you are looking at a painter’s palette, with multiple colors, primary, secondary, tertiary… along with shades and tints. You can perceive all those colors (in a physiological sense), yet you choose to call them all orange. People outside your society can also see red, blue, green, yellow, but are puzzled that you choose to call them all orange. So your society has lost something. You cannot render the richness of what you see. At least in text form. Apparently.

Breq has been outside the Orange empire for 20 years. She has collected countless songs, that she is constantly humming, which represent other norms. She seems to comprehend the stories in those songs. Yet when she returns to the Radch, her lack of perception makes her seem increasingly dim, even while more emotionally aware. So the machine, the AI-in-flesh, makes more progress toward becoming an empathic “human/biological citizen,” than she does expressing the richness she saw outside her cultural frame. So for me, the “interesting experiment” did not become “more successful as the novels advanced.”

Perhaps I was looking for a resolution where a “genderless” society, imposed by the state to a default orange/she, begins to move toward a multi-colored, gender and sexually fluid society.

(disclaimer (just in case of contrarian, overly serious, sometimes literalist, possibly humorless interpretation: the use of color is strictly metaphorical. Skin color apparently is an issue for Leckie, although kept below the surface in the novels. She has said that hopefully the TV show doesn’t “whitewash” the characters.)

Excellent analysis, Liz. I think you have gotten to the heart of what the trilogy was about. When the first book came out, everyone was all focused on the gender-neutral pronouns and talking about gender identities. But in the end, that issue was only a warm-up for the real question of identities, an example that put the real issue into perspective, kind of like the conversation with Translator Zeiat about cakes and game counters. The real question of identities in the trilogy was the difference between “she” and “it,” between those characters perceived as people, and those characters perceived as tools.

I loved these books, and loved Breq, whose mix of insight and cluelessness was so endearing, and whose fierce sense of justice was so admirable. And I was delighted that Leckie gave her a relatively happy ending.

@12 – “The Omaugh Anaander was described as a small, feminine figure”, sure. But that doesn’t mean the Omaugh Anaander was female.

For that matter, what does “feminine” even mean, if you’re thinking in Radchaai?

Kinda late to the party here, but I’d held off on reading this until I finished Ancillary Mercy. And I’m glad I did.

Anyhow, one of the things that really hit me in the third book was how the stuff about the pronouns and other cultural things opened me up more to internalizing the Radchaai attitudes toward AIs without thinking about them, so when the covers were torn off that distinction, it hit me in much the same way as when I first came to a realization of my white privilege.

I also feel certain that without the previous books, Translator Zeiat would have come across as far more silly and slapstick, but the way everything was built up made it easier to see her as just someone who came from a completely different set of reference points and attitudes, who would have made absolutely perfect sense if I’d been able to view things with her background.