Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

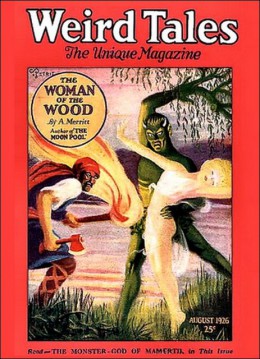

Today we’re looking at A. Merritt’s “The Woman of the Wood,” first published in Weird Tales in 1926.

Spoilers ahead.

“To McKay the silver birches were for all the world like some gay caravan of lovely demoiselles under the protection of debonair knights. With that odd other sense of his he saw the birches as delectable damsels, merry and laughing—the pines as lovers, troubadours in their green-needled mail. And when the winds blew and the crests of the trees bent under them, it was as though dainty demoiselles picked up fluttering, leafy skirts, bent leafy hoods and danced while the knights of the firs drew closer round them, locked arms with theirs and danced with them to the roaring horns of the winds.”

Summary

McKay, a pilot sapped “nerve and brain and soul” by WWI, has taken refuge in a lakeside inn high in the Vosges. The surrounding forests delight him, for McKay loves trees and is acutely aware of their individual “personalities.” At first the trees heal his wounded spirit; it’s as if he “sucked strength from the green breasts of the hills.” But soon he senses that the tranquility is tainted by fear.

The source of the unease appears to be a half-ruined lodge across the lake. McKay fancies the lodge wars with the forest, for ragged stumps and burned ground glare around it like battle scars. McKay’s landlord says old Polleau and his sons don’t love the trees, nor do the trees love them.

McKay’s drawn to a coppice of silver birches. Fir trees circle them like needle-mailed knights guarding damsels. He often rows across and lies dreaming in the shade, ears tingling with mysterious whispers. From his boat, he sees one of Polleau’s sons chop down a birch. It falls into a fir, so like a wounded woman that McKay seems to hear its wail. Then a fir bough strikes down the son.

For two days McKay senses the coppice appealing to him for help. He rows back through mists that twist into fantastic landscapes. Voices chant; figures flit among the mist-curtained trees. One mist-pillar transforms to a woman of “no human breed.” Her green eyes have no pupils, but in them sparkles light “like motes in a moonbeam.” Her hair is palest gold, her mouth scarlet, her willow-lithe body clad in a fabric sheer as cobwebs. She bids him hear and speak and see, commands echoed by other voices. McKay finds himself in an emerald-lit clearing floored with golden moss. More scantily clad and fey-lovely women appear, along with green-kirtled swarthy-skinned men, also pupil-less, also elfin.

The coppice is still there, but insubstantial—“ghost trees rooted in another space.”

One woman lies “withering” in the arms of a green-kirtled man. She must be the felled birch. Nothing can save her, the first woman tells McKay, but perhaps he can save the rest from blades and flame. She kisses McKay, inspiring him with the “green fire of desire.” He cools off when she says he must slay the Polleaus. When he pushes her back, the green-lit world again becomes the coppice. Slay, the trees continue to whisper.

Rage drives McKay toward the lodge, but reason intrudes. He could have imagined the greenlit world and its fey denizens, right? The mists could have hypnotized him. Forget slaying, then, but he still must save the coppice. He asks Polleau to sell him the little wood, so he can build his own house there. Polleau refuses. He knows who told McKay that they mean to destroy the coppice. Look what the fir tree did to his son—knocked one of his eyes from his head! Seeing the wound, McKay offers to dress it properly. That softens Polleau into giving the history of his people’s enmity with the forest. Back when they were peasants, the nobles would let them starve and freeze rather than grant permission to cut firewood or keep the trees from their fields. The feud is old. The trees creep in to imprison them, fall to kill them, lead them astray. The trees must die!

McKay returns to the coppice like a messenger of impending doom. The Polleaus have made the innocent trees symbols of their former masters, just as he himself must have imagined them into consciousness, transferring his war-bred sorrows. But no sooner does McKay decide the trees are just trees than he hears their voices again, wailing farewells sister to sister, for the enemy comes with blade and fire.

Again enraged, McKay opposes the Polleaus. He fights with the unwounded son. Fir-men urge him to let the son’s blood flow. Somehow a knife comes to McKay’s hand. He plunges it into the son’s throat. As if the spurt of blood is a bridge between worlds, green-clad men and white women attack the Polleaus, killing them.

Seeing blood on his hands reopens the wounds in McKay’s spirit. Though the woman who kissed him earlier reaches to embrace him, he flees to his boat. Looking back he sees her on the shore, strange wise eyes full of pity. His remorse fades on the row to the inn. Whether the dryads of the coppice were real or not, he was right to prevent its destruction.

He gets rid of the bloody evidence. Next day the innkeeper tells him the Polleaus are dead, crushed by trees. It must have been a rogue wind, but one son had his throat torn out by a broken branch sharp as a knife! Weird enough, but the son also clutched cloth and a button torn from someone’s coat.

The innkeeper tosses this “souvenir” into the lake. Tell me nothing, he warns McKay. The trees killed the Polleaus and are happy now. Even so, McKay had better go.

McKay leaves the next day, driving through a forest that pours into him the farewell gift of its peace and strength.

What’s Cyclopean: Internal alliteration and rhyme are the order of the day. “He saw hatred nicker swiftly” is a nice one, but the most impressive is a long passage in which “faery weavers threaded through silk spun of sunbeams sombre strands dipped in the black of graves and crimson strands stained in the red of wrathful sunsets.” That may take a while to parse, but it’s pretty.

The Degenerate Dutch: Aside from the male dryads being “swarthy,” a descriptor without any malice attached, “Woman” doesn’t dwell on race or ethnicity. [ETA: On the other hand, you can judge that Weird Tales cover for yourself.] Here there’s no war but the class war, even when chopping down trees. The dryads take the part of French nobility, the last remains of the not-so-distant Revolution, Gentry dealing with commoners who don’t know their place—or know it, and would like to switch out with the trees and have their own turn on top.

Mythos Making: This story is more Dreamlands than Mythos—the world reached through the mist of the lake is particularly reminiscent of the Strange High House.

Libronomicon: No books.

Madness Takes Its Toll: McKay doubts his sanity—which seems pretty reasonable when talking to trees. He also doubts Polleau’s sanity—which seems pretty reasonable when someone carries a generations-old killing grudge against trees.

Anne’s Commentary

I wasn’t surprised to read that one of Abraham Merritt’s hobbies was raising orchids and “magical” plants like monkshood, peyote, and cannabis—if mind-altering means magical, the last two plants certainly qualify. But the point is, he had a certain affinity toward the vegetable kingdom, and that philia finds fictional expression (in spades) in our hero McKay. He’s no mere tree-hugger—he’s a tree-whisperer! I think of famed gardener Gertrude Jekyll, who wrote that she could identify tree species by the sounds their leaves made in the wind, the various murmurs and sighs, patters and clatters, fricatives and sibilants. She was also sensitive to individual differences in plants, though not so prone to anthropomorphize them as McKay. He can tell whether a pine tree’s jolly or monkish, whether one birch is a hussy and another a virgin.

Evidently pines and firs are masculine, see, whereas birches are singularly feminine. I can kind of see that. At least when Merritt describes the birch-dryads, they’re not limited to Madonnas and whores. Some are alluring, but others are mocking or grave or curious or pleading. The fir dudes are more homogeneous, except for the one who cradles the withering birch, both furious and tender.

After a couple of reads, this story has grown on me like the bluet-spangled moss of the trees’ spirit-reality. Merritt/McKay’s sensitivity to the natural world feels genuine. Yeah, there’s some description here as violet as violets, as lilac as lilacs, as deep a purple as Siberian Iris “Caesar’s Brother.” Overall, though, the botanical landscape comes alive on the language level as well as on the story level. On the story level, it has me really rooting for that beautiful little coppice, mourning the slow-withering birch-maid. And, man, are there a lot of puns in this paragraph, or is it just that we’re a species so dependent on plants that our language naturally cultivates many botany-tinged expressions?

Heh, I said ‘cultivates.’

Hunh, hunh.

Ahem.

The sentient or conscious plant is a fairly common SFF trope, and it’s positively rampant in poetry, where roses may be sick at heart (Blake) and where daffodils dance their yellow heads off (Wordsworth.) One of the two examples this story brings to mind is (naturally) Lovecraft’s treatment of vegetation. Yeah, nice Dreamlands locations are full of gardens and flowers and graceful trees and all, but the flora are pretty much set decoration, atmosphere, or (as in the case of “Azathoth’s” camalotes) cool-sounding names.

More striking are Lovecraft’s nasty plants, like those atmosphere-enhancing trees that are always so twisted and gnarly and ancient and over-large and grabby of bough and overfed with unthinkable sustenance. They dominate Martense country and Dunwich and cemeteries galore. The forest surrounding the Outsider’s subterranean home is quite the forbidding place, its trunks more likely gigantic roots if you think about it after the big reveal. Lesser vegetation tends to be lank, sickly, pale, or downright fungous.

Closest to Merritt’s conception of arboreal sentience are the olives in “The Tree.” Sculptor Kalos loves to meditate in a grove — some suppose he converses with dryads. After he dies (perhaps poisoned by envious Musides), a great olive tree grows from his tomb. Later it kills Musides by dropping a bough on him. Has Kalos become a dryad himself, inhabiting the olive? Has another dryad taken vengeance for his sake?

But most menacing is the vegetation in “Color Out of Space,” from the unearthly hue of everything growing near the afflicted farm, to the noisomeness of its produce, to its sky-clawing trees with spectral glowing branches. But these plants don’t have innate souls or presiding spirits—they’re merely vessels, conduits, infected with alien life.

Lovecraft rarely gets sentimental about the shrubbery.

His opposite, far closer to Merritt, is J. R. R. Tolkien. He’s as fond of gardens and all growing things as any hobbit, and there are no “trees” more sentient and soulful than the Ents, who “herd” their less mobile and talkative brethren. All Tolkien trees seem to have souls, with which the Ents and Elves can communicate. Treebeard hints that trees can become more “Entish” or Ents more “treeish,” implying a continuum of behavior within one species rather than separate species. Ents, when finally roused, can be feisty enough. The more “treeish” Ents called Huorns kick way more animal butt than Merritt’s firs and birches, with their ability to move fast under cover of self-generated darkness. From Merritt’s descriptions, there’s a wide range of personality and proclivity in trees; they’re basically joyful and benevolent, but they can be dangerous, too, and in the end profoundly alien—humans can’t plumb the ancient depths of their language and experience, being such hasty (short-lived) creatures.

I had a parting thought that some of Lovecraft’s long-lived races could be seen as plant-like! Well, there are the “Fungi” from Yuggoth, but even they are more arthropod-crustacean-mollusk-echinoderm-protozoan than “treeish.” That “Tree on the Hill” wasn’t really a tree. That green stuff’s ichor, not sap. Where designing sentient races is concerned, Lovecraft’s more an animal than a plant man.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Merritt was part of Lovecraft’s most polynomous collaboration, the five-authored “Challenge From Beyond.” We’ve already covered Moore, Howard, and Long—thus Merritt’s presence here. But while Merritt was a fellow pulp author, the style and substance of “Woman of the Wood” are very different from most of Lovecraft’s work. Maybe a little Dreamlands-ish?

The internet tells me that Merrit’s language is “florid” and has aged poorly. It’s certainly no worse than Lovecraft’s and a good deal better than Poe’s. Sure, he’s prone to the odd in-line alliteration, and is trying a little too hard to sound poetical, but judged on his own terms, the language does what he’s trying to do. The French mountain lake feels like something one would expect to find on the border of ethereal fairyland—not that that’s hard—and the dryads successfully come across as both beautiful and alien. And, more of a trick, they successfully come across as both potent forces of primal vitality and incredibly fragile. That seems about right for a nature spirit.

The Merritt-Lovecraft connection that jumps out most strongly is World War I. McKay’s a veteran, recently returned from the trenches and recuperating in France. Like Lovecraft, Merritt was in fact American; I can’t find any indication that he fought himself. But the war overturned everyone’s idea of a stable world, whether or not they saw it firsthand. It works well here as the impetus for our narrator’s actions.

When that impetus leaps to the fore, it’s the most powerful part of the story. The dryads of the glade beg McKay for help; Polleau explains exactly what his family holds against the trees. Survival versus vengeance, but vengeance with all the grievances of the French Revolution behind it. Temporarily dissuaded, our narrator retreats—but when Polleau and sons approach with axes, he at last obeys the entreaty to “slay.”

And pulls back in bloody-handed revulsion as all the horror of the war comes rushing back. He’s still someone who kills at another’s word. The real and fantastic merge, and it no longer matters whether the cycle of violence involves elves, or just humans.

Then this vital emotional conflict… just sort of peters out. McKay wakes freed once more of his trauma, entirely unconflicted about having killed Polleau’s son. Not only that, but the threat of discovery ends with no more price than the loss of a hotel room. The green Gentry triumph as they couldn’t in the Revolution, and everything is hunky dory. I’m all for happy endings, but this one doesn’t fit the story.

World War I runs quietly through all Lovecraft’s horror, only occasionally visible above the surface. Where it flows, though, it carries the idea of something terrible just out of sight, something that means nothing will ever truly feel safe again. “Woman of the Wood” could have gained a lot if it didn’t go to so much trouble to shove all that existential terror right back in its box.

For example—what would happen, if McKay stayed with the dryad who ordered him to kill? In painted battle scenes, allegorical women often hover above and exhort soldiers to loyalty and courage and bloodshed. Usually the implied rewards of their gratitude are also allegorical, but it’s clear here that they could be quite real. Our dryad may be genuinely grateful, even perhaps in love with her rescuer (why not, it’s not like the dryad boys are great conversationalists)—but it doesn’t seem likely to be a healthy relationship.

[ETA: In looking for cover images, I discovered that the always-excellent Galactic Journey reviewed a reprint of this story way back in 1959.]

Now that we’ve been properly introduced to all the authors, next week we’ll cover “The Challenge From Beyond” by *deep breath* C.L. Moore, A. Merritt, H.P. Lovecraft,

Robert E. Howard, and Frank Belknap Long .

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in April 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.