There are many ways to structure a magic system in a fantasy story, and even though expressing magic through language is one of the most obvious methods for a story to utilize (“abracadabra!” and all that), it is also somewhat rare. Language is precise, complex, and in a constant state of change, making it daunting for an author to create, and even more daunting for a reader to memorize.

There are some interesting shortcuts that fantasy stories have utilized over the years, however, some of which are utterly fearless in tackling the challenge inherent in crafting a complex magical language.

For Beginners

Just use Latin: Supernatural, Buffy, et al.

The Roman Catholic Church pronounced Latin as the official language of the church back in 313 C.E. and still utilizes it for sermons and rituals. In the first millennium, the Church used Latin to “dispel” demons from this Earthly plane during exorcisms, the thinking being that God’s word and sentiment was most clearly and directly expressed in Latin, and what demon could withstand such a direct proclamation?

As such, Latin has become identified as containing a mystical, ancient, and otherworldly quality. TV shows and movies with an urban fantasy bent to them, like Supernatural or Buffy the Vampire Slayer, tend to fall back on this shorthand in order to avoid having to create and explain an entire mystical language to their viewers. Latin has become the go-to, off-the-shelf basic package for magical language in a fantasy story.

Memorize these terms: Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling

Most spells in the Harry Potter series require a vaguely Latin-esque verbal incantation, although author J.K. Rowling adds a bit of complexity in that these verbalizations need to be demonstrably precise and usually must be accompanied by a specific wand movement. The language magic in the Harry Potter series is one of the few areas of Rowling’s world that remains simplistic: being essentially a dictionary of terms and phonetics to memorize, which is in marked contrast to other worldbuilding aspects to the Harry Potter world. (The Black family tree has more complexity than the world’s entire magic system does.) This makes the language magic easy for young readers to internalize, turning the magic into a series of slogans (“Accio [peanut butter sandwich]!” “Expecto Patronum!” “Expelliarmus!”) instead of a list of terms.

There is an aspect to Rowling’s language magic that interesting and that we may see explored further in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: non-verbal magic used by adults. There are many instances in the book series where older characters are able to create complex, and massively powerful, spells without needing to verbalize them. Does this suggest that language magic in the Harry Potter universe is simply a bridge, a tool of learning, to more complex, non-verbal magic? Or does language magic simply become a reflex over time?

For Intermediates

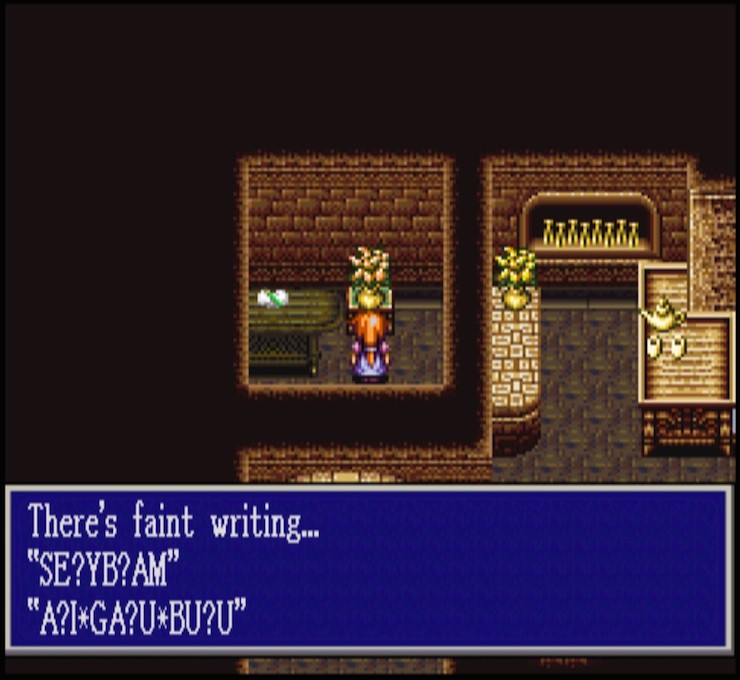

Mix and match until something works: Treasure of the Rudras

Treasure of the Rudras is a 16-bit RPG game that harkens back to the wistful days of Final Fantasy, Chrono Trigger, and Breath of Fire. Although where the aforementioned games would give you predetermined spells to select and use, Rudras differed by creating a basic system that allowed the player to construct their own spells by grouping specific syllables of a language. Crafting a basic element name would summon the weakest version of that spells, but experimenting with adding specific suffixes and prefixes would enhance the strength of those spells, and unlock other added effects. This system was beautifully simply in execution, allowing the developers to skip creating an entire magical language while still giving players the impression that they were active participants in learning and using a magical language. Fittingly, beating the game requires the player to use what they’ve learned of this syllabic magic language system to create a functional and unique spell.

Let’s have a chat: The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim

With the introduction of dragons into the Elder Scrolls franchise came the introduction of the dragon’s language. Functionally, this is the same syllabic system as seen in The Treasure of Rudras, although without the interactivity. Your character is able the use the dragon’s language as form of intensely powerful magic (known as a Thu’um, or Shout), and you do learn specific words and calligraphic symbols for this language, but this only allows the player to translate some of the game’s narration as opposed to crafting new spells.

Still, Skyrim does have one unique use of magical language: The realization that a dragon roasting you with its fire breath is probably just it asking if you’d like a cup of tea.

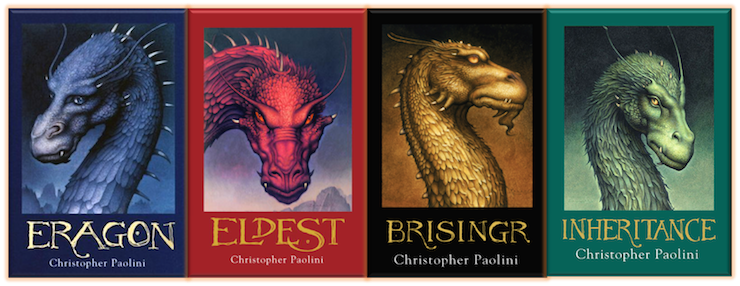

Negotiation: The Inheritance Cycle by Christopher Paolini

What makes the Ancient Language (also the language of the elves) in the Inheritance Cycle unique is that it is a language that affects the universe, but does not allow the universe to read the intent of the caster. So if a character wants to heal a broken shoulder, they can’t simply incant “Heal!” in the Ancient Language. Rather, the caster must be very specific in what it wants the universe to do–move this muscle back into place first, then fuse these two bones, then move that fused bone, etc.–in order to use magic in any useful sense. Where simpler language magics are about finding the correct key for an existing lock, language magics of intermediate complexity add interaction and negotiation with a third party into the mix. In essence, it’s not enough to know the language and its terms, you have to be able to converse in that language, as well.

For Advanced Users

Fluidity and interpretation: The Spellwright Trilogy by Blake Charlton

Magic in Blake Charlton’s Spellwright trilogy, which concludes with Spellbreaker on August 23rd, is a complete character-based magical language consisting of runes that can be formed into paragraphs and larger narratives by the reader and the characters within the fantasy world. Where the Spellwright trilogy focuses its story is in the interpretation and fluidity of that language, asking how a magical language would progress if interpreted and expressed by an individual who would be considered dyslexic in that world. Every Author (as the wizards in this series are called) must be a sufficiently advanced linguist capable of duplicating the runes perfectly in order to use the magic. However, language, while precise in use, is not static over time. Terms change rapidly (ask someone living in the 1980s to “google” something for you, for example) and pronunciations change over regions. (NYC residents can tell you’re from out of town by the way you pronounce “Houston St.”, for example.) The Spellwright series explores the rigidity of language and the necessity of fluidity and error with incredible detail.

The world emerges from the language: The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

The universe in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings was “sung” into existence, and one of the reasons Tolkien is such an undisputed master of the fantasy genre is that he did the work of creating the language that created his universe! Not only that, Tolkien saw how a singular language would be affected by region, nationality, and time, and derived the languages of Middle-earth as branches from that ur-language. Magic that we see used in The Lord of the Rings is entirely-based on that ur-language, and the characters that use it most effectively–Sauron, Saruman, Gandalf, the elves–are the ones with the most direct connection to that originating language.

It is a testament to the power of the magical languages in The Lord of the Rings that they can reach beyond their fictional basis to affect the real world. Conversations can be conducted in Elvish, a child’s name can be (and has been) constructed from Tolkien’s language (“Gorngraw” = impetuous bear!), and the weight of its utility in turn makes the fictional Middle-earth feel incredibly real.

JKR primarily uses soft Latinate words for the neutral or less violent spells, lots of almost Slavic harsh consonants for the kill spells.

There’s also the concept of “true names” which is finding the ur-word for an object to give the user power. Ursula K. Le Guin uses this in her “Earthsea” fantasies.

Books drawing from Islamic magical traditions seem to use verses of scripture as magical delivery systems, see Throne of the Crescent Moon and Range of Ghosts.

Butcher’s Dresden Files uses pseudo-latin but says it’s just a mnemonic and insulation against power rather than inherent meaning.

The Roman Catholic Church still uses Latin in the 21st century?

I once thought up a concept for a magic system that used language to direct your will. Let me know if anyone has read something similar to this: Magic responds to the user’s will; the easiest way to channel it is to vocalize what you want. Thinking what you want is dangerous, as other thoughts and desires can clutter your mind. When you speak, you can’t think anything at the same time (try it). Since your mind already associates certain concepts with the language you speak, you need to speak an entirely unfamiliar language in order to narrowly focus your will. So early magic users came together and created an entirely new language for all magic users. Thus, regardless of what language you speak, you learn this language and free your mind of any unwanted associations. You associate phrases in this new language with whatever spell you want to achieve and eventually your mind associates that phrase with that exact spell and it becomes easier to non-verbally cast it.

Bitter Seeds, by Ian Tregillis, comes to mind as well.

I thought of Michelle Sagara’s Elantra Chronicles while reading this. Most of Kaylin’s magic is manipulating words.

Cool post!

Always glad to see commentary about Tolkien.

Doctor Who: “The Shakespeare Code” :)

Interesting that the Catholic Church chose Latin instead of Greek.

Christopher Stasheff’s Wizard in Rhyme series plays with this as poetry, particularly Rhyme is the spell.

L.E. Modesitt’s Spellsong Cycle also comes to mind, as Music causes the magic, with singing the spell making it more powerful.

@5 What you describe at first makes me think of David Eddings Belgariad and Malloreon. These books have a magic system called “the Will and the Word” where the user must direct his or her will to a certain intent and then channel it with the correct word. It made for a really good reading experience as far as I remember.

Another example of language magic would be the AonDor of Brandon Sandersons Elantris. Users would draw symbols in the air, reminiscent of an iconographic language. The basic character would dictate the type of spell while modifying strokes could be added for more power or specificity. Nearly limitless in power and capability but geographically bound to just one city, and you needed an incredibly steady hand of course.

There is a world/RPG created by a group Hungarian writers called M.A.G.U.S. In that world, there still lives a race from the beginning of time, even before dragons or elves who can affect the world simply by soeakung their own language. Mere mortals of the 7th age simply die or go insane if they hear a simple word. A single one of these beings, aquirs, could destroy the whole of civilization if they wanted. Luckily, they do not much care.

This magic can pass on if you digest/ingest body parts from an ancient aquir but sooner rather than later you will die as those body parts will caus rapid cancer-like cell growth in your own body and you need to make sure you se that one or two words wisely before you die.

The creatures from the 2nd, 3rd ages also have magical languages but less powerful. Naturally, the magics (as there are many different versions) of the current, 7th age is mostly based on language used in the 6th age.

You wish now that someone would translate that to English, don’t you?

The “scriveners” of N. K. Jemisin’s “Inheritance” trilogy learn the language of the gods and perform magic by writing in it.

@5 The Inheritance trilogy mentioned above works this way. The main character is taught magic relies on spoken commands, but later sees elves disregard this, and learns that vocalization is a crutch that protects the user from messing up their thoughts.

I’d like to mention two universes with language-based magics: Modesitt’s Spellsong Cycle and Sanderson’s Cosmere. In the Spellsong universe music and lyrics create a spell. The protagonist’s musical training is a major asset as she’s thrust into an otherwise hostile environment. In the Cosmere, the magics of the planet Sel are performed mainly through writing the desired effects in magical languages (the shapes of the characters based on the country of origin). Selish magics are almost like computer programs. One of them allows you to basically construct an alternate history, and then convince the universe that your written history is better, changing the object described.

@2 – I was also thinking of naming magic (such as Name of the Wind).

@@.-@ – um…yeah. I can’t tell if that’s a joke or not, but Latin Mass is still very much a thing and as far as I know, encyclicals, proclamations, councils, etc are still published/conducted originally in Latin, and then translated. The idea (then) being that it was a universal language. Now that’s not so much the case but it still sticks around.

Have to admit, I read it just to see if Tolkien would show up as he is basically the ultimate example (although ‘magic’ per se in his books doesn’t really exist in the flashy sense).

Great article. Let’s not forget the late great Sir Terry Pratchett. Now there was a fellow who knew how to use language and to stretch it to its limits. His posthumous book A Slip of the Keyboard also contains many pearls of wisdom for budding fantasy writers.

Isn’t this how *all* magic systems work? That is, magic, definitionally, is accomplishing real-world effects through the use of language or linguistic systems alone. There may be other trappings of ritual but language is core.

Language is the key way magic in Earthsea works, too!

Fun article. Thanks.

@5: Thinking something else and speaking at the same time is possible, but difficult and requires practice. As a synchronous translator, I have to listen to the speaker, process their words into another language in my mind, then speak those words all at the same time. Granted, it’s not quite the same as holding a totally different thought in your mind while speaking on a different subject, but it is possible

@18 But aren’t thinking the same as you’re speaking, it’s the just the formatting changes? When I get my bilingualism working properly I’m not translating to myself, I’m perceiving the meaning of the words irrespective of the language. I’m not doing French to English to Meaning but straight from [language] to meaning. @5 seemed to be suggesting to think and speaking about different meanings. [language] to meaning to [other language] is still impressive af but not the same thing.

Maybe that’s also the difference for @16? For systems where the language is magic, the spell is straight from language to magic; not language to [ritual/meaning/process] to magic. The power is more in the words rather than the speaker or the audience.

Piers Anthony used a rhyming magic system for the main character in the Adept series. That was my first.

@5: >When you speak, you can’t think anything at the same time (try it).

I’ve always been able to think and speak at the same time, especially if the speech is memorized or something like song lyrics. Other people don’t?

If you watch, say, people answering questions without being immediately sure of the answer, at quiz games or in politics, you see them speaking filler words first: “Who painted the Last Supper?” “The guy who painted the Last Supper is, um, Leonardo.” They were thinking, searching for the answer, while speaking.

If some people can do this and some can’t, your magic would immediately have two different levels of users.

“Supernatural” – s10ep17, “Inside man” :D Dean can’t join in the seance when he’s out drinking with Crowley :D

Daaamn, I see mratin @10 (and also Kyptan @13) have beat me to AonDor.

And I’m pretty sure the “Inheritance” cycle’s magic can also be called the “true name” magic:

“He knows our true names, Eragon… We are his slaves forever.”

— Murtagh

Also, one book that nicely uses the magic of words and language IMO is Naomi Novik’s “Uprooted”. For example, when Agnieszka complains to Sarkan that the spell vanastalem bothers her because makes her dresses all too fancy and complicated and heavy with too much lace and brocade and everything (so unwearable for her), he advises her to just drop part of the word – mumble it, slur it or something. She tries vanalem and the gown she’s wearing after vanastalem becomes a simple brown dress with a green sash.

I also kinda like the idea JKR is introducing – you do not need long spells that are impractical when needed urgently (in contrast, for example, the series “Charmed”, where most of the spells were like short poems, if I remember correctly), but in order to have the spell work, you must be proficient enough to use it, merely knowing the words is not enough (Expecto Patronum being an excellent example)

Suzette Haden Elgin’s Ozark trilogy featured people doing magic using notations from transformational linguistics.

Luke, not all magic systems work through words. Wheel of Time, for example.

@16 I’ve read a number of books where the magic simply comes from elements combined to create an effect. These are more “technological magics,” so to speak, in which the virtues of the ingredients and the proper technique combine to make a magical effect, much like a vinegar and baking soda volcano. The effect comes from an elemental reaction, and the “spell” is more like a device used to give it shape, purpose, and/or context. Sometimes they’re combined with linguistics, but sometimes not. Other times, the magic comes from pure intent or instinct. I recently started reading Diana Wynn Jones’ Chronicles of Chrestomanci, in which some magics are done via written or spoken language, but some are just done, without speaking or thinking specific commands. The books differentiate the types of magic. One is “witchcraft” while the other is “enchanter’s magic.” There are hints at other types of magic as well – “magician’s magic,” and a special type of magic done on a certain alternate world that is sort of backwards and folded over from other magical techniques. Some kinds of witchcraft in this series is apparently done by combining ingredients with no mention of a linguistic component. Kind of like potions in Harry Potter. HP also hints at more instinctual magic with the kinds of magic done by Harry and Tom Riddle before they learn of their magical powers. The magic comes from the urgency of the desired outcome, not from a specific idea of what needs to be accomplished to create that outcome. Once growing up a bit and learning of it in the context of “wizardry,” of course, the characters can’t duplicate those effects without years of careful study and practice. I think this is rather profound.

There are different kinds of magic in Ilona Andrews kate Daniels. The strongest is word magic that is used by Roland among others.

@7: I also thought of Michelle Sagara’s Chronicles of Elantra. Kaylin Neya has the words to the ancient language of creation inscribed on her body and finds that she can work magic by manipulating those words. In fact, all of the magic in the books is based on this ancient language of the Creators that only survives in fractions. Telling stories in this language can actually shape the lives of the listeners. Like LeGuin’s Earthsea books, naming something with its true name in the ancient language is a way to manifest the concept encompassed by the word. The fascinating thing about Kaylin’s use of the ancient words and symbols inscribed on her body is that she cannot actually read or speak the ancient language but can intuit which words or symbols to insert in a phrase to change whatever magical phenomena she is trying to “fix.”

The Music of the Ainur has long been one on my favorite stories in Tolkein’s world. The concept is inherently beautiful, and it is refreshingly less teleological than most creation myths. Moreover, it reads like a genuine origin story that would be told by people (Elves, Ents, Tom Bombadil and Doldberry, etc.) who revere not only song/music/poetry but also the notion that both harmony and dissonance are inherent in the nature of the world. It is a myth that naturally connects with and underscores the cultures described in other stories of Middle Earth.

There are a couple wonderful meta aspects, too. The idea that the world and its peoples are the words/music/thoughts of the godhead made physically manifest has such unmistakable echoes of the opening chapters of Genesis and John that I’m sure Tolkien and C.S. Lewis must have had some fascinating conversations about it. Not to mention how thin that fourth wall gets when the narrative describes a creator sorting through themes to find the ones that work together best, and then weaving those together to create an entire world.

—

If incantations and wand gestures in JKR’s world are primarily learning tools and mnemonic devices, rather than necessary elements of magic, I think the whole published story hangs together a bit better. As the books progress, the characters rely less on rote recitations and more upon mindset and intuition—much like the way people learn advanced skills in the real world. Indeed, the importance of deep & broad understanding of the effects of words and actions ends up being a critical plot element of the final book: Voldemort’s superficially wide, but actually selective and shallow, understanding of magic leads to his downfall; yet he is fatefully crippled near the very end via Harry’s casting of a spell that is not only nonverbal but primarily a side-effect of his focus upon what (well, actually, who) he finds most truly important. Hence, one aspect of the story arc is an exploration of the notion that the greatest power of words lies in what they can kindle in our hearts and minds; upon reaching a certain level of understanding, knowledge and emotion are enough and words become unnecessary.

Can’t believe that Diane Duane’s Wizards series isn’t mentioned…The entire system is based on language, the wizardly “Speech”, the language in which the universe was spoken into being, being the main foundation of the series’ magic. Spells are spoken, (To a point, then sometimes it seams as though the spell is speaking itself, using the wizard as it’s conduit.) and, on top of changing the world around the wizard, can also change the wizard themselves.

In Patricia C. Wrede’s Mairelon duology (a Regency England with magic), the magic system requires both gestures and spoken words. But magicians deliberately cast spells in languages that are not their native tongue, because using another language forces you to concentrate and narrows your focus, while speaking in your native language can put too much power in the spell. So a spell for an English wizard might be in Latin, Greek, or Hebrew, but never English.

It’s not a book, but the Gargoyles cartoon distinguished between faerie magic (which is in Shakespearean rhyming couplets, because the fair folk can use magic as easily as we might freestyle rap) and human magic (which is in Latin, based on specific spells passed down presumably from Roman sources).

When the Latin starts rhyming, it means that something really bad is about to happen.

There’s the concept of language as an occult force in its own right, as in Ruthanna Emrys’ Those Who Watch. On the darker side, it shades into the idea of language-as-disease, destructively infectious memes such as the Pontypool plague or the disturbing works of (in)famous pulp writer Helmut Finch.

@14: Latin was never a universal language; it was simply every Western learned person’s second language, just as the Greek of the New Testament was the second language of every traveler (and of anyone who dealt with travelers) in the eastern Mediterranean.

@30: In Poul Anderson’s “Operation Salamander” (part 2 of Operation Chaos), language departments (e.g., of the university the story happens at) all expanded when the principles of magic were worked out (~2 generations ago), because incantations must be done in some other language — in the previous story (“Operation Afreet”) the narrator cobbled together a spell using pig-Latin to get himself out of a tight spot.

@33 Clarification: per Anderson, spells are in another language just-because; writers could get away with a quick handwave on the way to action much more readily 60 years ago than now. (Although Anderson did try to use physics to explain some magic, with clumsy results: e.g. trolls stoned by sunlight are still dangerous because transmuted carbon yields a radioactive isotope of silicon.)

other interesting examples come to mind: In Garth Nix’s The Old Kingdom series (now no longer a trilogy!!) existing symbols are drawn upon from a spiritual well of symbols and put together a bit like language (see Lirael for more details). Also I was thinking of Warbreaker in response to @5, wherein magic resides in what are called Breaths, and have many effects, but to Awaken objects, you have to recite these phrases or words with a kind of intention that matches your words.

Interesting article and I’m loving the comment thread! :)

The idea of a true name having power comes from Egyptian mythology. In ancient Egypt, each god had five names, each associated with one of the five elements, and priests/worshipers would use the names in different prayers or rites.

When I first started to study computer science, the ability to write logical steps and turn them into a program seemed almost magical to me. It might even make a good basis for a magic system: write code on a magic scroll and get a complex spell! But there can be terrible consequences if your code is buggy… And if your network of program-spells gets too complex it might just develop into a magical AI!

But really, language is crazy and mathematical and just awesome. Human society wouldn’t exist without it. A few words can change the world. What could be more magical than that?