Here’s a story: a young woman is kidnapped by a sailor and forced to sail away with him and a crew. The sailor ‘loves’ the woman, but she never asked to be dragged onto the boat. A storm blows up, kills the sailor and crew, and drives the boat northward. The woman finds herself alone at the North Pole, thousands of miles from family, with no crew to help her get home. But then a mysterious portal opens in front of her. Rather than face a cold and lonely death, the woman walks through, and finds herself in a strange new world where all the creatures speak, where there is only one language, pure monotheism, and absolute peace. The creatures welcome the woman as their Empress, and they all work together to make scientific discoveries.

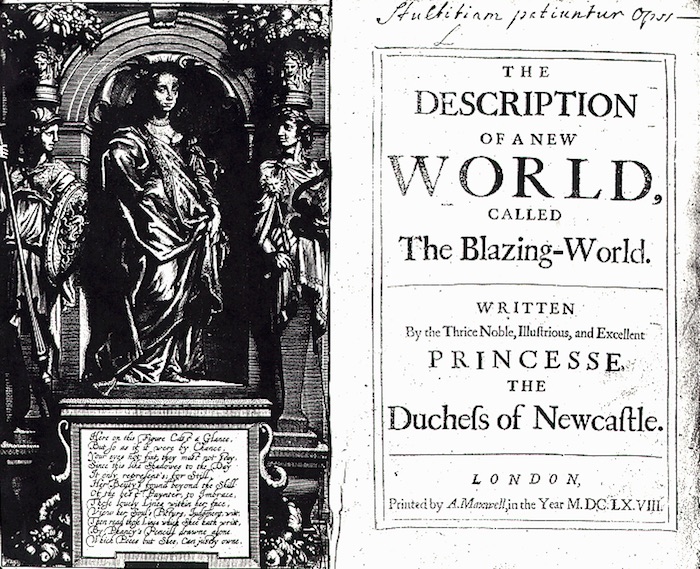

This is the basic plot of “The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World”, which was written by Duchess Margaret Cavendish, and published in 1666. As the intrepid archivists of Atlas Obscura have pointed out, it may be our earliest example of science fiction and it was written by a shy, lonely woman who, despite being mocked for having career aspirations, married fantasy, proto-sci-fi, and philosophical thinking 150 years before Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein.

Margaret Cavendish was born in 1623 to a family of relative means. She became a Maid of Honor to Queen Henrietta Maria, whom she followed to France in exile during the English Civil War. When she returned to England, she was a Duchess with a loving, supportive husband, and between his influence and her own charm and intelligence she was able to observe experiments at the British Royal Society, write, and, increasingly, seek fame through outrageous social behavior. If she’d been born a man, she would have been a poet, and probably a dandy, snapping off witticisms right along with Alexander Pope. Instead she went through painful ‘treatments’ that were meant to help her bear children, and she was mocked as “Mad Madge” by other nobles.

Now obviously there are other contenders for “earliest sci-fi author”, and you could argue that this story is more in line fantasy/philosophical exercise typical of the time—Cavendish does write herself into the book as the Duchess, a friend of the Empress. The two women are able to disembody themselves, and as (gender-free!) souls they travel between the worlds, occasionally possessing Cavendish’s husband to give him advice, particularly on sociopolitical matters.

But, the reason I accept Cavendish as a science fiction author is that her story is fueled by her study of natural philosophy. She (like Mary Shelley, later) attempted to take what was known about the world at the time, and apply a few of the ‘what-ifs’ of scientific experimentation to it, rather than just handwaving and saying “God probably did it.” The Empress employs the scientific method in her new world, investigating the ways in which it differs from her own. Cavendish also writes of advanced technology, as Atlas Obscura observes:

[She] describes a fictional, air-powered engine that moves golden, otherworldly ships, which she says “would draw in a great quantity of Air, and shoot forth Wind with a great force.” She describes the mechanics of this steampunk dream world in precise technical detail. All at once, in Cavendish’s world, the fleet of ships links together and forms a golden honeycomb on the sea to withstand a storm so that “no Wind nor Waves were able to separate them.”

Unlike Mary Shelley, Cavendish published her book under her own name, and it was actually included as a companion piece to a scientific paper, Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, where it was probably supposed to provide a fun story to help lighten the dry academic work it was paired with. You can read more about Cavendish and her work over at Atlas Obscura. And if that isn’t enough feminist proto-sci-fi for you, Danielle Dutton has written a novel based in Cavendish’s life, Margaret the First, which was released earlier this year, and you can read the full text of The Blazing World here!

Frankenstein is a gothic horror novel, like Dracula, not SF.

If Brian Aldiss accepted Frankenstein as the first science fiction novel (and, in Billion/Trillion Year Spree, he does), then that makes it sf in my book. :) I can’t remember if he discusses the Duchess’ book or not, but it sounds intriguing, and you make a good case that we should consider it sf, as well.

And that “golden honeycomb” of ships sounds an awful lot like the climax of Guardians of the Galaxy, doesn’t it? :)

@3 it is also what many colony insects to do protect themselves from large dangers like drowning or being blown away by wind.

I’ve blogged a couple of times about Margaret Cavendish and her book The Blazing World since hearing about it while visiting Bolsower Castle where she wrote it. A remarkable woman who was way ahead of her time. It’s a total shame she is so overlooked.

@2/wrychard_wrycthen: Frankenstein is a gothic horror novel and a science fiction novel. While Dracula is about a supernatural creature, Frankenstein is about a creation of science and technology. Indeed, though it seems fanciful today, the book was inspired by contemporary scientific thinking about the nature of life and death. Advances in resuscitation and experiments in galvanism had led to uncertainties about the definition of death and whether it was truly irreversible. Shelley’s own mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, had been revived from an attempted suicide by drowning, so Shelley would’ve had reason to be aware of these questions. Here’s an interesting article about the scientific thinking that inspired the book:

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-science-of-life-and-death-in-mary-shelleys-frankenstein

Even I didn’t realize just how grounded in contemporary science the book was. Critics at the time even cited it for its realism.

(Although Dracula is also a book about technological innovation, in a way. It’s an epistolary novel consisting of journals, interview transcripts, and news reports, and a lot of its story is about how Mina Harker compiled the book as a key element in the investigation of Dracula, with the indispensable aid of that marvelous new invention, the typewriter. The whole book is practically an extended typewriter commercial.)

That dry academic work that the Blazing World was paired with, Observstions Upon Experimental Philosophy, just came out as an affordable edition from Hackett Publishers.

https://www.amazon.com/gp/aw/d/1624665144/

Full disclosure: I edited it. But hey it’s timely!

I find it very interesting that a book with “The Blazing World” in the title was written by an English woman and perhaps, judging from the appearance of the word on that page, printed in London, all in the very same year of the Great Fire of London. That’s an event that every British person has heard of, even to this day, though I’m not sure how famous it is elsewhere in the world. It’s hard to see the year 1666 without thinking of it – teenage mental associations with a great, fire-based disaster and the number 666, you see.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_London

@3: As I remember (and it is a veritable eon since I read it), the gist of Aldiss’s argument was less that Frankenstein was the first “science fiction novel”, more that it was the first science fiction “novel”: namely, Frankenstein exhibited greater realism than its predecessors and was less reliant on unlikely incidents (aside from the whole creating life business) to drive the plot. Aldiss classed earlier works of speculative prose fiction as “scientific romances” rather than novels.

@9/SchuylerH: I’m not sure I see the distinction between a novel and a romance, given that the word for “novel” in both French and German is roman. And the term “scientific romance” wasn’t coined until 1845, more than two decades after Frankenstein came out. These days the term is generally used to refer to the works of writers who were active at the time the term was in use, like Verne, Wells, and Burroughs. And Verne’s works were very much the hard SF of their day, grounded in what Verne considered realistic by the best scientific understanding of his era.

Okay, I found Aldiss’s essay online. I only have time to skim it now, but what he actually says is that Frankenstein anticipated the scientific romances of later writers like Wells. The predecessors he discusses are Gothic novels; Frankenstein is itself very much a Gothic novel, but with the innovation of a modern, scientific grounding.

@10: This essay goes some way towards explaining the not-entirely-transparent distinction between a novel and a romance.

Aldiss, in his essay, uses “scientific romance” to refer to “more respectable” works exploring similar territory to the stories of the American pulps. SFE uses the term in the fashion common in Britain, referring to those works of speculative fiction produced before the influence of pulp “science fiction” became widespread outside of America. (Indeed, Wells described his own works as scientific romances in the title of an omnibus edition.)

I do wonder where my memories of the essay come from: I might have conflated Aldiss’s views with those of Stableford and a couple of others.

Aldiss, at a later reading, had this to say on Frankenstein‘s significance:

Christendom was full of angels and lots of fibs about the planets being inhabited. One’s knee deep in these discarded fantasies, but it was Mary Shelley, poised between the Enlightenment and Romanticism, who first wrote of life – that vital spark – being created not by divine intervention as hitherto, but by scientific means; by hard work and by research.

That was new, and in a sense it remains new. The difference is impressive, persuasive, permanent.

@11/SchuylerH: What Aldiss says is true, but the article I linked to earlier reveals that there’s more to it than that. It’s not just the basic conceit that the creature was the product of science rather than divinity or magic; it’s the fact that the concept in the book is directly extrapolated from real scientific hypotheses and questions of the era. Galvanism and the discovery that drowning victims could be resusciated had raised questions about how life and death were defined, and the “What if” question beyond that, which scholars of the era were actually debating, was whether science could achieve resurrection or even the creation of new life. So it wasn’t just a horror fantasy with the pretense of a scientific justification, but a story that was actually grounded in the scientific ideas and investigations of the period, as much as Verne’s writing about submarines and airships or Clarke’s writing about rockets to Mars.

@6 Re technological innovation in DRACULA, Mina Harker is not only using a typewriter, but she’s transcribing Dr. Seward’s oral reports recorded on the cylinders of an early Dictaphone-type device, less than 10 years after Edison’s first phonograph.

There’s also the use of modern medicine to rescue those attacked by Dracula through the use of blood transfusions, another recently developed technology. Although, apparently in the Stokerverse, blood-typing is not an issue, since no attempts are made to match up donors and recipients.

@13/Russell H: Good points. But I just love how the actual creation of the book itself is a key plot point in the book. It’s so meta. It’s like a modern found-footage movie. I don’t actually like found-footage movies that much, but it’s intriguing to see something so “modern” in such a classic novel.

Interesting side discussion on Dracula that folks are having. Is it because the central element of the vampire is supernatural that it doesn’t get classifed as proto-sf, or even science fantasy?

Speaking of meta-books, did anyone else read S., the book “produced by” (not written by – I forget the author) J.J. Abrams a few years back? It was pretty cool as a “found artifact” — chock full of marginalia, laid-in notes and documents, all in a “real” novel (complete with library markings on the spine) — but I found I couldn’t stick with it. Maybe if I’d read the “novel” first and then gone back to track the story in the margins…

@15: In the introduction to Leslie Klinger’s The New Annotated Dracula (a book I really should get round to, #129) Neil Gaiman describes Dracula as a “Victorian high-tech thriller”, which is close enough.

@14 One could also say that DRACULA is a “modern” version of the “epistolary-novel” literary device that was first popularized in the 1740’s by Samuel Richardson with his novels “Pamela” and “Clarissa.”

@17/Russell H: Epistolary writing was quite common in the 19th and early 20th centuries, especially in fantasy fiction. Or at least, it was common to present a work of fiction as a recounting of someone’s true story. Frankenstein is Captain Walton’s account of Victor Frankenstein’s account of the creature’s account. A lot of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s books were prefaced with “Here’s a tale that was told to me by its narrator” or “Here’s a journal I found” or the like. Of course, the Sherlock Holmes stories were told by Watson and their publication in The Strand was often metatextually referenced within the stories. Wells’s The Time Machine was supposedly Wells’s recounting of a tale told to him by an unnamed friend who claimed to be a time traveller. (Although several adaptations have put Wells himself in the role of the traveller, either implicitly as in the George Pal version or explicitly as in Time After Time.)

This was pretty common for fiction in general, but I think it was especially favored by fantasy/SF because of the inherent implausibility of the premises. It was basically a way of lending the fantastic tales an air of reality by claiming that they were recountings of true stories — or at least recountings whose tellers alleged them to be true, with the author going “Look, I’m just passing this along, I’m not saying I believe it.”

Indeed, it occurs to me to wonder if the shift away from first-person journalistic/epistolary novels to a more detached omniscient-narrator third-person style could be correlated with the emergence of film. Cinematic storytelling is almost always objective third-person (with a few exceptions, like the opening minutes of the Fredric March Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde or the entirety of Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake or the recent Hardcore Henry), so maybe it helped audiences get more used to seeing stories told in that way.

For the interested, I have determined that Project Gutenberg does have The Blazing World as well, here:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/51783

(I’m going to snag it from there, since they have it as an EPUB!)

@18. Yeah. Lovecraft is another example.