Psychologist Carl Jung believed that many cultures across the globe produced similar myths due to a sort of unified subconscious, the idea that deep down in our collective psyche, we all embraced the same symbols in an effort to explain the world. But what if it were far more simple than that? What if these linked myths merely migrated along with the people who told them? One scientist has provided strong evidence to that tune, piecing together together a global mythic tapestry that is thousands of years in the making.

Over in Scientific American, doctoral candidate Julien d’Huy has used computer models and phylogenetic analysis to track the movement of mythic tales across cultures and continents, over thousands of years. d’Huy starts with the example of the classic “Cosmic Hunt” myth–a story where a person or persons track an animal into the forest, where the animal escapes by becoming one of the constellations in the sky–and explains that Jung’s idea of an intrinsic, embedded concept of specific myths and symbology doesn’t hold up across the board:

If that were the case, Cosmic Hunt stories would pop up everywhere. Instead they are nearly absent in Indonesia and New Guinea and very rare in Australia but present on both sides of the Bering Strait, which geologic and archaeological evidence indicates was above water between 28,000 and 13,000 B.C. The most credible working hypothesis is that Eurasian ancestors of the first Americans brought the family of myths with them.

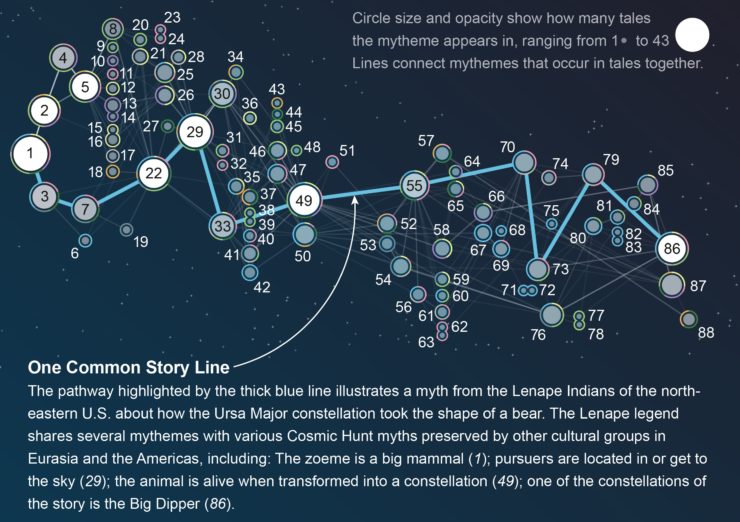

This led d’Huy to create a phylogenetic model, more commonly used by biologists to track evolution, to create a myth tree that tracked the evolution of a single story. By the d’Huy had identified 47 versions of the story and 93 “mythemes” that cropped up throughout these various versions at different frequencies. Tracking these changes made it possible to hypothesize when certain groups migrated to different areas based on the introduction of new story mythemes and changes made to the tale. d’Huy’s model showed that “By and large, structures of mythical stories, which sometimes remain unchanged for thousands of years, closely parallel the history of large-scale human migratory movements.”

Other myths were also tested using this model, yielding fascinating results. The Pygmalion story, the Polyphemus myth, and tales of dragons and serpents all showed evidence of the migratory patterns of humanity dating back thousands of years. It is possible that these models will help future scholars to identify ancestral “protomyths,” or the base tales that many of our widespread myths herald from.

Read more about Julien d’Huy’s research over at Scientific American.

A shame Robert Holdstock didn’t live to see this.

Thanks for alerting/linking us to this! Fascinating research. I’ve always resisted the Jungian collective unconscious explanation, since it makes the symbols/stories preexist the cultures that use them, and thus keeps one from critiquing the symbols on the basis of the concrete cultural power relationships they reflect, which critique is the heart of feminism and critical social theory and one of the great intellectual advances of the 20th century. So it’s great to have organized data to refute the Jungian theory.

It’d be interesting to read Dune in terms of that.

I’m interested whether this analytical method can eventually be scaled up to handle more complex literature–epic poetry, novels, etc. (but woe unto the poor grad students tasked with coding all the mythemes present in War and Peace or the WoT series!). The resulting relationships among the works themselves would be a rich area to explore, but perhaps even more interesting would be to identify any branch points that can be associated with notable historical events, technological changes, or discoveries, i.e. things considered truly momentous enough to have permanently imprinted upon our cultural legacy.

Very interesting news. But why do they have to be mutually exclusive? This research doesn’t totally wipe out Jungs theory on the collective unconscious. Why do these myths still resonate with us today or appear in our dreams when by rights they should have disappeared long ago as their physical relevance is gone. Jung is largely unknown and misunderstood by the mainstream anyway even though I agree that some of his work is shaped by his understanding as a man in the early to middle 20th century.

This is so cool!

I’m surprised no one mentioned Joseph Campbell, since this was the main thrust of his work all a the monomyth.