In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown will look at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The United States is divided by concerns about a stagnant economy and trade imbalances. The nation is still conflicted about a long and inconclusive war. A charismatic and bellicose Republican has replaced the last President, a scholarly and thoughtful Democrat. The new President promises to increase military spending while cutting back on the bureaucracy and balancing the budget at the same time… That’s right, folks, it’s time to travel back to the 1980s, and look at a work of military science fiction from the Reagan Era.

I can’t remember exactly when I bought a copy of Hammer’s Slammers, my first encounter with the work of David Drake. I don’t think that it was a first edition, since I bought it in the early 1980s. It was a time when military SF was becoming more popular, but this book was something unique. It had a profound effect on me, as it was like no SF I had read before: the combat was brutal, the costs high, and the carnage was described in vivid detail. These soldiers were not fighting for country nor glory, but simply for survival, and for those who fought beside them. The book was a “fix-up,” however—a collection of stories primarily drawn from Galaxy magazine, padded out with some essays that explained the settings and technology in the stories. The second book published in the “Hammer-verse,” Cross the Stars, was a full novel, but was a different sort of tale, being a retelling of the Odyssey in an SF setting.

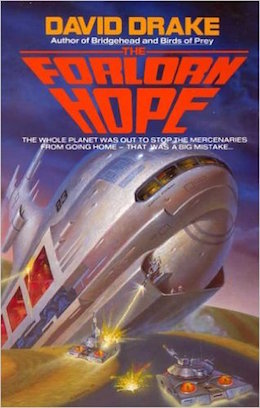

For this review, I have decided to focus on another early Drake novel, The Forlorn Hope. While this novel is not set in the universe of Colonel Hammer and his mercenaries, it takes place in a very similar milieu and is a vigorous and compelling book on its own, capturing many of the themes that weave their way throughout Drake’s work. As Drake said himself about The Forlorn Hope, it too draws on classical sources: “I used Xenophon’s Anabasis–the March Upcountry–as a model for the opening situation but based the remainder of the milieu more on the Thirty Years War.” But it wears those influences lightly, and stands well as its own tale. And for those who are familiar with Hammer’s Slammers, but are unfamiliar with this particular book, The Forlorn Hope serves as a lesser known treasure, a book that any Hammer’s Slammers fan will enjoy.

David Drake was born on 24 September 1945, and studied Latin and history as an undergraduate before going to law school when the draft intervened in his life. He ended up serving in Vietnam and Cambodia as a member of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment; his military role took advantage his education, and he worked in intelligence as an interrogator. That did not mean he avoided combat, as he also served as a loader on a tank. He was deeply affected by his experience. He had wanted to write before he went to war, but now he had a mission as well: to show how horrible war could be. As Drake himself has said, his writing was a form of “self therapy.” He had assistance from writers in his local area (Manly Wade Wellman and Karl Edward Wagner), but Drake’s career was helped immeasurably by editor Jim Baen. It was Baen who bought the first Hammer stories for Galaxy, and Baen as an editor at Ace who suggested collecting the stories into Hammer’s Slammers in 1979. When Baen moved on to Tor Books, he brought Drake and The Forlorn Hope along with him—and when he finally started his own company, Baen Books, it was Baen who made future Hammer stories a centerpiece for his catalog.

The Forlorn Hope was published by Tor Books as a paperback original in 1984, with a vigorous and stylized cover by Alan Guttierez. It told the story of a company of mercenaries led by the battle-hardened Colonel Guido Fasolini. They have been hired to augment Federal troops of the 522nd Garrison Battalion, who are protecting a mining operation from the Republicans, or “Rubes,” as they are called. The Republicans are led by a fanatical religious sect, and their units have chaplains who serve in roles much like the political officers in the old Soviet Army. When Fasolini took the contract, it looked like easy money, but fortunes have turned against the Federals, and in struggling with adversity, they themselves have become fanatical and cruel to their own troops. The Rubes have promised death to any mercenaries hired by the Federals, and what appeared a lucrative deal is now a death trap.

The Forlorn Hope was published by Tor Books as a paperback original in 1984, with a vigorous and stylized cover by Alan Guttierez. It told the story of a company of mercenaries led by the battle-hardened Colonel Guido Fasolini. They have been hired to augment Federal troops of the 522nd Garrison Battalion, who are protecting a mining operation from the Republicans, or “Rubes,” as they are called. The Republicans are led by a fanatical religious sect, and their units have chaplains who serve in roles much like the political officers in the old Soviet Army. When Fasolini took the contract, it looked like easy money, but fortunes have turned against the Federals, and in struggling with adversity, they themselves have become fanatical and cruel to their own troops. The Rubes have promised death to any mercenaries hired by the Federals, and what appeared a lucrative deal is now a death trap.

The only Federal with any sympathy for Fasolini and his company is Lieutenant Albrecht Waldstejn, the 522’s Supply Officer. He comes from a family of questionable loyalty, which explains his lowly position in the army, but he does the job as best he can, trying to maintain his dignity in difficult times. His two subordinates, Privates Hodicky and Quade are cast-offs, reviled by the others in the battalion. The 522nd is a paper tiger, with dispirited troops led by cowardly and ineffective officers. Fasolini’s team is a collection of misfits and malcontents—fierce fighters, but malcontents nonetheless. His “Executive Officer,” Lieutenant Hussein ben Mehdi, is charming and persuasive; useful in negotiations, but amoral and no military leader. The three sergeants are the backbone and tacticians of the unit. Sergeant Roland Jensen is their gunner, and shepherd of the unit’s single artillery piece. Sergeant Johanna Hummel is a fierce and capable combat leader. Sergeant Mboko is quieter, but no less capable. The unit is made up of a variety of difficult characters. Churchie Dwyer and Del Hoybrin, for example, are bootleggers and thieves. Other troopers range from experienced soldiers to new personnel recruited without any skills simply to round out the unit table of organization. There is a space freighter, the Katyn Forest, at the facility waiting to load ore.

The book opens with bombardment of the camp by a Rube spaceship. Dwyer and Hoybrin save their lives but lose their still in the attack. Lt. ben Mehdi uses the attack as an opportunity to corner one of the female troopers, but his attempt to rape her is interrupted by Sergeant Hummel. Sergeant Jensen uses his gun in an unauthorized manner, and is rewarded with a lucky shot that destroys the attacking spaceship. The Katyn Forest is damaged in the attack, and everyone is shaken, as they realize that it is probably the prelude to a Rube assault. Waldstejn stretches the rules to provide a power receptor unit to the Katyn Forest that they can use to travel between power pylons and reach the dockyards of the capitol city, where they can effect permanent repairs. The Republicans radio an offer to the leaders of the 522: if they surrender and swear loyalty to the new religion, they will be given places in the Republican Army. They must simply capture Fasolini’s unit and turn them over to the Republican Army, which means certain death for the mercenaries. Only Waldstejn sees anything wrong with this, and when Fasolini realizes what is happening, he is killed before he can reach his unit.

Waldstejn offers the mercenaries assistance in escaping, and his privates join him. They fight their way out of the camp, but they are a long way from safety. The Republicans overrun the 522nd, and incorporate the unit into their forces. Waldstejn realizes that the Katyn Forest is their only chance of escape, and he and the mercenaries formulate a plan to fight their way back into the camp, now reinforced by Republican tanks. Even after they reach the camp, they will have to fight their way across miles of hostile territory before finding any measure of safety. I will leave my summary there to avoid spoiling any further details of the plot.

The Forlorn Hope is a page-turner, fast-paced and hard to put down. The characters, with the possible exception of Lieutenant Waldstejn, are hardly sympathetic, but compelling and well-realized. The military technology of the Hammer-verse is well thought out, with weapons that fire projectiles in a plasma state, and hovercraft replacing wheeled and tracked vehicles. Notable in The Forlorn Hope is Drake’s description of the use of drones in combat, a technology that was still decades in the future when he wrote the story. The tactics his infantry use against tanks ring true when I compare them with stories my father told of facing Panzers during the Battle of the Bulge. There is a realism and a grittiness to his tales that is lacking in many other military SF books.

As the 1980s progressed, and beyond that to the present, Drake’s career went from one success to another. The Hammer series expanded to many volumes. Drake has written a number of standalone books, with Roman and classical settings being used in many. He became a noted fantasy author, with the book Lord of the Isles being the first in the long and successful “Isles” fantasy series, and the “Books of the Elements” series beginning with The Legions of Fire. Due to his success, Drake was asked to participate in a number of anthology series, and he co-authored a number of books as well, notably the “Belisarius” series with Eric Flint and the “General” series with S. M. Stirling and others. He is currently working on the “RCN” or “Republic of Cinnabar Navy” series, standalone novels inspired by the Aubrey/Maturin novels of Patrick O’Brian, which feature protagonists Daniel Leary and Adele Mundy. His career has been long and varied, and he has garnered a great deal of respect along the way.

As the 1980s progressed, and beyond that to the present, Drake’s career went from one success to another. The Hammer series expanded to many volumes. Drake has written a number of standalone books, with Roman and classical settings being used in many. He became a noted fantasy author, with the book Lord of the Isles being the first in the long and successful “Isles” fantasy series, and the “Books of the Elements” series beginning with The Legions of Fire. Due to his success, Drake was asked to participate in a number of anthology series, and he co-authored a number of books as well, notably the “Belisarius” series with Eric Flint and the “General” series with S. M. Stirling and others. He is currently working on the “RCN” or “Republic of Cinnabar Navy” series, standalone novels inspired by the Aubrey/Maturin novels of Patrick O’Brian, which feature protagonists Daniel Leary and Adele Mundy. His career has been long and varied, and he has garnered a great deal of respect along the way.

During the 1980s, Drake and other military SF writers generated a great deal of controversy. Those were the days when the Cold War was at its height, and many thought that the saber-rattling of the Reagan Administration would lead to the end of civilization instead of the collapse of the Soviet Union. There were many in the SF community who branded the work of Drake and others as “war porn,” stories intended to thrill and excite readers by glorifying war. I had the opportunity to meet Drake and hear him in panel discussions during this era, and found this interpretation to be far from the truth. Anyone who accused him of glorifying war did not understand his work, nor the intentions of the man himself. Today’s readers might not realize it, but The Forlorn Hope generated some criticism of Drake from his fellow military SF writers when it was initially released. The female characters that we now take for granted in war stories were extremely rare in those days. In The Forlorn Hope, without any explanation or context, Drake portrayed a military where women routinely fought alongside men in all combat roles. He didn’t advocate it, or judge the effectiveness of the practice—he simply presented it as the way things were done. I remember a great deal of discussion of that aspect of the book, and remember being bemused by the fact that writers who could imagine intelligent aliens and travel between stars not being able to accept women doing what men had done in the past.

David Drake has had a long and illustrious career. The Forlorn Hope may not be widely remembered now, but it stands among his best work, and is an excellent distillation of his themes of the bonds between soldiers and the horrors of war. And now, it’s time for me to hear from you: if you have read it, what were your impressions of The Forlorn Hope? What other works by Drake stand among your favorites, and why did you like them?

[Note: This article originally stated that The Forlorn Hope was set in the same universe as the Hammer’s Slammers series. That turned out to be incorrect, and the article has been amended accordingly.]

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy.

I’m a big fan of David Drake and his Hammer’s Slammers stories, but I don’t recall ever reading this one. I’ll have to check it out. Anyone who accuses Drake of writing “war porn” is clearly ignorant of either war or his stories or both. He’s realistic, which is completely different.

I like Northworld but always wanted it to go in a slightly different direction than it did. I remember loving it’s take on powered armour, but for me the plot kind of petered out in an unsatisfying way. I believe this is because (as is common for him) Drake based this on some real world mythology and/or oral epic which has a different structure than modern novels.

In fact, that is something that would bug me in other Drake works as well (e.g. Redliners IIRC).

Drake, along with fellow Vietnam vet Joe Haldeman, helped set a new bar for the realistic depiction of science-fictional warfare: his grimy, grunt’s eye view, coupled with the historical awareness from his classical education, can be as formidable a force as any of his future regiments. I would agree with Drake that Redliners is his most significant book: I haven’t yet read The Forlorn Hope but I’m going to order it.

This is an unrelated question, but by what strange augury is the posting date for Front Lines and Frontiers decided?

ETA: an interesting “behind-the-scenes” essay.

@3: Front Lines and Frontiers posts normally go up the first week of each month; there’s no set day/time beyond that.

Are you sure this is technically a Slammer’s universe book? My memory – and I can’t believe I have brain cells occupied with facts like this – is that while it had some similar tech (hovertank) it had enough differences (lasers and projectile weapons instead of magic plasma guns) that it was technically a different universe. It’s also an interesting counterpoint to the Slammer’s novels in that it’s from the perspective of the poor infantry outside the nigh-invulnerable tanks rather than those inside them. Overall I remember enjoying the book – some setpieces like the final battle are pretty impressive, and agree with many others that it’s unfair to lump the nuanced perspective of Drake with many other MilSF writers.

I love O’Brien but found the RCN books kind of a slog after a while – deliberately or otherwise, the assumed superiority of the lead characters and their culture over all others is kind of kind of tiring, and the mapping into the Age of Sail a little forced. Similarly, the Lord of the Isles books all settled into a repetitive pattern – characters get ominous portents, characters get separated, some have to travel through bizarre universes with some tough NPC helping before finally all being reunited to fight the end-boss.

#5 It’s not a Hammer’s Slammers universe; human nature is the same across universes but the tech varies. As you say there are technical differences and as I recall editorial differences as the Forlorn Hope was to be open to other writers.

I wouldn’t say the tanks in the Tet Offensive book Rolling Hot are any more invulnerable than the characters. As a shaggy dog story it’s among the farthest from space opera. Then again The Sharp End isn’t about tanks either

Notice that the assumed superiority of the lead characters and their culture in the RCN books is a characteristic and by no means a suggestion. The attitude is appropriate for both the Hornblower/Aubrey & Maturin roots and equally for the Roman/Latin antiquarian allusions found so often in Drake’s writings. Drake’s characters are well drawn. Daniel in the first book is amazed and grateful to find himself at loose ends in exotic places. As Daniel ages he follows the conventional pattern of the conventional fellow he is. Mr. Heinlein as another naval type of another age suggests I think in Tramp Royale an assumed superiority of his own culture even as Mr. Heinlein was busy pointing out faults in his fiction – but only washing dirty linen in private (Expanded Universe). Daniel Leary would feel superior where somebody who went native would be a different character. There are characters who do consider their own culture superior to Cinnebar. Sometimes shown as mistaken in context and sometimes shown as having a point.

The criticism that the Lord of the Isles books settled into a repetitive pattern is often heard. I would phrase it differently. Rather than settled I would say spiraled upward as the big bad became ever more powerful eventually god-like. Much of the travel will resonate like Silverlock for many readers of fantasy. It’s not obvious whether a missed allusion adds richness or not.

I’ve always seen Drake as pretty much the polar opposite of “war porn”. I’ve seen his works described as horror stories that happen to have a military context, and that sounds about right to me. Redliners was the peak of this tendency in his writing, for me, as he seemed to finally exorcise the demons of his Vietnam experience with that one.

I agree with Bruce @5 above that I do not believe that “The Forlorn Hope” is actually set in the same universe as the Hammer’s Slammers series. I believe it was originally intended to be the first book in a different series. For whatever reason this did not happen. I think it would be fair to say that Drake was exploring some of the same themes as he has used in the Hammer’s Slammers series.

As to the charge of David Drake writing “war porn”, I think anyone who says that really needs to work on their reading comprehension. Anyone who reads his stories and thinks Drake is glorifying war is a fool.

There was a tolerably well known SF critic (whose name I omit here) who sneered at Drake, writing that if Drake had ever actually been in combat he would not write about war with such enthusiasm. Drake, who is, of course, a veteran of combat in Viet Nam with the 11th Calvary, did not take this insult lightly. As part of his revenge for this ignorant piece of spite, Drake took the critic’s name and used it for a series of despicable minor characters in his books going forward. I have always thought this a most elegant piece of literary vengeance.

@2 and @3 I ran into a number of positive mentions of Redliners on the internet when preparing this article. So I picked up a copy at the used bookstore when I picked up the copy of The Forlorn Hope for this article (unlike other books I have reviewed, I couldn’t find this one in the basement). I had missed Redliners when it first appeared, and am looking forward to reading it.

@3 Thanks for the link to Drake’s website where information on The Forlorn Hope is located. I spent a number of hours touring the website; he has a lot of fascinating background information there.

@5, @6 and @8 When I wrote this article, I was convinced that The Forlorn Hope, while it does not share any characters with Hammer’s Slammers, was set in the same universe; certainly any differences in technology are minor, and the basic themes are there. But looking at my sources, I can’t find that anything in black and white that confirms my conviction. It could have been an assumption on my part, a longstanding assumption, but incorrect nonetheless. I have sent an email to Mr. Drake himself, and will let you all know what reply I receive. If I am wrong, I am certainly willing to admit it, and set the record straight.

Though many of the accusations against David Drake were misguided, ignorant, or simply wrong, there is an element of truth to the idea that he glorifies, not war, but warriors. His writing often praises loyalty and ability above more moral virtues, giving us characters who were excellent to their comrades and frequently awful to anyone outside their unit . Since we almost always saw those characters from the viewpoint of their comrades, readers got to see them through a lens that tended to magnify their camaraderie and bravery while playing down the importance of their cruelty. By writing from the perspective of soldiers, and emphasizing the soldier’s virtues, Drake frequently chose to neglect the civilian’s perspective on war. (With the exception of Redliners, by far his best book.)

All writing is shaped by the perspective of the narrator. Soldiers, like most people, tend to emphasize their own struggles and triumphs while neglecting the people outside their immediate circle. On any given planet the Hammer’s Slammers visit, completely innocent civilians die. But we see the world through the eyes of the Slammers, so each dead comrade is a tragedy, while the dead civilians are just a statistic.

@10: I agree that the focus is in the soldiers, and that can magnify the positive traits about them. But Drake never idealized them. They were portrayed, warts and all, as a varied bunch. Some were relatively decent people in bad situations, others were psychopaths or just pure evil. And as Drake wrote in one of his introductions:

“I kept the tone unemotional: I didn’t tell the reader that something was horrible, because nobody had had to tell me.”

And Drake was never blind to the plight of civilians caught up in the battles he described. That was the main focus of at least one short story, “Caught in the Crossfire”, and comes up repeatedly in others. If the soldiers in his stories had become callous or jaded, that seemed part of the horror to me.

@11 GBCarrera

I remember that story! We meet Margritte for the first time. It stuck with me because it’s such a fascinating inversion of the usual format of Slammers stories; though the mercenaries she first meets aren’t Slammers, they could be, and we get to see what professional mercenaries look like through the eyes of civilians trapped in a war zone. There’s still nuance; one of the soldiers seems to enjoy his work more than he should, one is a pleasant farmboy who’s just following orders, and the sergeant is entirely focused on getting the job done. But all of them are entirely willing to write off Margritte’s entire village as collateral damage, because that’s just the kind of thing that happens in war.

The Slammers are complicated. As the protagonists, they enjoy a natural advantage, and most of the narrators tend towards the “sympathetic professional” side of the mercenary scale; we get to see the worst elements, but we usually have someone more likeable to root for. As Drake himself points out in one story, though, the “good mercenaries” are working with Major Steuben. They’re all part of the same team, and they choose to be here; after a few tours, even privates could afford to retire on some backwater world, but they’re still with the regiment, killing people for money.

I still remember one story where the Slammers put down a rebellion by angry moss gatherers (it makes sense in context) to uphold the rule of a corrupt oligarchy. Most of the Slammers seem to come from poor agricultural worlds, and plenty of recruits left the farm for a chance to see the galaxy and earn real money. If they’d hadn’t run into a recruiting officer, they could be the rebels, facing down Hammer’s Slammers. And Drake does a good job of emphasizing this…yeah, you’re right, he doesn’t underplay the problematic nature of his protagonists.

So you’re right. Drake magnifies the positive qualities, which civilians might not fully appreciate, without underplaying just how much evil Hammer’s Slammers can do for a paycheck. Now that I think back, he was a good introduction to a different side of military science fiction, where the protagonists weren’t always on the side of righteousness and the good guys didn’t always win.

Notice that the assumed superiority of the lead characters and their culture in the RCN books is a characteristic and by no means a suggestion. The attitude is appropriate for both the Hornblower/Aubrey & Maturin roots and equally for the Roman/Latin antiquarian allusions found so often in Drake’s writings. […] Daniel Leary would feel superior where somebody who went native would be a different character.

Definitely true; mostly meant to say I found it grating in a way I didn’t in O’Brian, possibly because Daniel isn’t as likeable as Jack Aubrey, or at least as Jack Aubrey seen through Stephen Maturin’s eyes. Not necessarily a flaw, perhaps more a matter of taste and style.

I think the early books also suffered a bit from the superhumanity of the lead characters; I can recall O’Leary in his tiny corvette beating an entire fleet of larger vessels, which seems ironic in contrast to the Slammer’s books relative realism.

The criticism that the Lord of the Isles books settled into a repetitive pattern is often heard. I would phrase it differently. Rather than settled I would say spiraled upward as the big bad became ever more powerful eventually god-like.

One could apply the same description to Dragonball Z, I suppose.

#13 Maybe so. Dragonball Z doesn’t mean anything to me. I’m guessing it’s a multi-level game in which characters power up as they progress through levels? Certainly there is a market place/reader tension between a multivolume story each volume more or less complete in itself and a single story spread across multiple volumes – cf talk of dividing Tolkien or Dune or a multitude of other works. That very notion has been discussed on this board.

Each of the first 5 volumes of Lord of the Isles can be read as complete in itself – followed by the next level.

After a market analysis the Lord of the Isles conclusion Crown of the Isles was deliberately written across three volumes. Likely enough some mismatch with expectations for a multi-volume fantasy series hurt the Books of the Elements which do stand alone well enough. There is some continuity. The young girl’s crush on a soldier boy from the frontier in the first Fire doesn’t end in marriage until the last volume when they’ve been through a lot together (no apologies for a spoiler if that spoils a boy meets girl story you aren’t going to like it anyway).

It appeals to me that Mr. Drake’s writings are much the same but different. The normal pattern, shared with C. J. Cherryh, of a tight 3rd person annoys some readers. Mr. Drake has varied narrative patterns as in the time shifting Venus books and occasional first person as in one of the Francis Drake books and the next RCN book as a conscious change.

Maybe Lord of the Isles would have met expectations better with at least one of the narrative threads stretched across the next book so that the books could not stand alone? More complete foreshadowing would have been easy enough as a teaser. Still for my money, and I do have multiple copies the Isles like the Elements are rich in allusions and otherwise. I don’t like the current fancy for asking the reader to buffer the series while waiting for the next book in an endless series to play out.

#14

Not so much the lack of an ongoing multivolume plot – that’s actually kind of refreshing in the era of multivolume epics – but that the structure within each standalone volume was so similar. Of course, that may have been deliberate true of lots of other series as well (especially outside of SF), but it did produce a sense of sameness compared to loosely-linked series that experiment or flip elements, or that have more evolution of characters. Eventually I reached the point where I literally could not tell if I had read a given volume when i saw it in a bookstore, and so trailed off.

That being said, I did read and enjoy several of them (and several RCN books, and several other of Drake’s series), and if you’re in touch with him you should be sure to pass on my considerable admiration for his work – the fact that I’m quibbling with structural details should be taken as a weirdly positive sign.

@5, @6 and @8 You were correct, and David Drake himself confirmed it; The Forlorn Hope is not set in the same universe as Hammer’s Slammers. I had thought for years that it was, and looking back at his website, the information that I was wrong was right in front of me while I prepared this article–it just goes to show that long held opinions are hard to dislodge. The article has been amended accordingly, and I thank you all for setting me straight.

@10 Your analysis is a good one. Drake presents his stories in a clear and even blunt manner, letting the readers draw their own conclusions. And his viewpoint is more often than not the viewpoint of the soldiers; a viewpoint where the lives of comrades are far more precious than the lives of others.

@13 I never thought that Dragon Ball would be cited in a discussion of David Drake’s work, but Dragon Ball Z is a pretty clear example of repetitive storytelling. I started losing interest in the tale when Goku lost his tail, and the series began to focus on one tournament after another.

The Forlorn Hope has always been a favorite of mine, maybe even my favorite Drake novel. The combination of betrayal, reluctant command, and the pain associated with making the honorable choices always appealed to me (as a person who didn’t have go to war). As great as Pritchard and Steuben were in the Hammer’s Slammers series, Waldstejn and his erratic warriors seemed more uncertain and thus more real in their decision-making than the Slammers’ disciplined crew. As for Drake’s other work, At Any Price and The Sharp End are my favorite Slammers novels, while Birds of Prey and the Belisarius novels are also faves by turning history into science fiction in very cool ways. In many ways, all of Drake’s work mashes science fiction and history into fantastic narratives, and they make me think about how the world constructs us, but some resist.

David Drake’s work in both the General and the Belisarius series had a profound effect on my life. They’re a large part of what put me on the path to studying history and writing fiction.

I now have The Forlorn Hope: I don’t feel I can add anything in particular to the preceding article and discussion but I’m enjoying it. Drake’s latest newsletter is out: he mentions that he’s currently writing an RCN book with a single new viewpoint character.

When I read the comments here it is glaringly apparent that none of them are Vets, Drake has been a fan of mine ever since I picked up the 1st slammers book, he presents war as it really is on the battle field. The barbarity and the inhuman extermination going on in the present war’s are something Drake foresaw years ago. Its laughable how politicians talk about the deaths of thousands of people as collateral damage, not even seeing them as human being. The Slammers never had that problem, Men .Women ,Children , dogs or cats it didn’t matter, if you threatened a Slammer you died, they had more honor than the people today who while raining death down on people or kidnaping them, talk about morality and compassion. Civilized people want to believe their military is somehow good and honorable, that they would never kill babies or innocent people. When I was a Marine if we had been told to sweep a Ville’ and kill everyone in it, we would have done it especially if we had been taking Kia or Wia, we would have felt bad about it the next day, but we would have done it. David Drake, Heinlein and the other military Sf authors are on the sharp end of anti-war , because the truth that they present to an ignorant world is one of the few things that might save this world.