It seems that some writers set up dystopian environments with the express aim of fixing them by the end of the book (or series). This is particularly true of YA dystopian fiction, the category in which my Steeplejack series most obviously fits, but I’m particularly interested in how such dystopias come about and how the characters in those stories survive, using the means at their disposal to resist the status quo.

The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood (1985)

This is one of several books I could have put on this list which seem especially—even painfully—topical right now and have gotten a lot of attention in the last year or so (Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm being other obvious possibilities), and not merely because of the new TV adaptation. The focus is, of course, on gender, the Republic of Gilead (once the United States) having stripped women of the most basic rights (including the right to read). While it may seem unlikely that a civilized country could take such a retrograde step, the circumstances which create this culture in the book—the rise of a Christian fundamentalist movement which asserts its ruthless influence after an attack kills the President and most of Congress—are unsettlingly plausible.

This is one of several books I could have put on this list which seem especially—even painfully—topical right now and have gotten a lot of attention in the last year or so (Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm being other obvious possibilities), and not merely because of the new TV adaptation. The focus is, of course, on gender, the Republic of Gilead (once the United States) having stripped women of the most basic rights (including the right to read). While it may seem unlikely that a civilized country could take such a retrograde step, the circumstances which create this culture in the book—the rise of a Christian fundamentalist movement which asserts its ruthless influence after an attack kills the President and most of Congress—are unsettlingly plausible.

The Machine Stops E.M. Forster (1909)

A novella (at most) which—with staggering prescience—looks forward to a version of earth in which people are isolated, every aspect of their lives mediated by a central “machine” whose operations are viewed with almost religious awe. The story centers on the machine’s gradual apocalyptic failing and the people’s inability to either repair it (all technical know how having being lost) or to live without it. It’s a bleak indictment of a culture so obsessed with labor saving technology that they lose touch with their own bodies and any meaningful notion of mental independence.

A novella (at most) which—with staggering prescience—looks forward to a version of earth in which people are isolated, every aspect of their lives mediated by a central “machine” whose operations are viewed with almost religious awe. The story centers on the machine’s gradual apocalyptic failing and the people’s inability to either repair it (all technical know how having being lost) or to live without it. It’s a bleak indictment of a culture so obsessed with labor saving technology that they lose touch with their own bodies and any meaningful notion of mental independence.

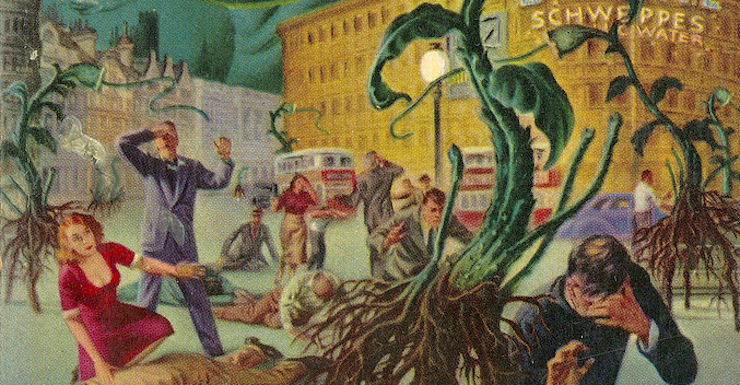

The Day of the Triffids, John Wyndham (1951)

The nightmare premise of this book is that, after a night in which a dazzling meteor shower (which may actually be orbiting weapons) leaves most of the British population blind and therefore at the mercy of the triffids: giant, mobile, venomous and carnivorous plants produced by genetic manipulation. What follows is the chaos of trying to survive not just the triffids, but the humans (individual and governmental) which are attempting to exploit the situation to their own ends.

The nightmare premise of this book is that, after a night in which a dazzling meteor shower (which may actually be orbiting weapons) leaves most of the British population blind and therefore at the mercy of the triffids: giant, mobile, venomous and carnivorous plants produced by genetic manipulation. What follows is the chaos of trying to survive not just the triffids, but the humans (individual and governmental) which are attempting to exploit the situation to their own ends.

Riddley Walker, Russell Hoban (1980)

Set in southern England a couple of thousand years after a nuclear holocaust, this remarkable book depicts not just the lives of the survivors but their garbled cultural memories, much of which is rendered in the very words they use. The people hold on to the vestigial traces of things their society once valued, the meaning of which has long since been lost. Against this strange and shadowy second Dark Age, the title character (in a quest reminiscent of an old Star Trekepisode!) seeks to relearn the lost art of making gun powder.

Set in southern England a couple of thousand years after a nuclear holocaust, this remarkable book depicts not just the lives of the survivors but their garbled cultural memories, much of which is rendered in the very words they use. The people hold on to the vestigial traces of things their society once valued, the meaning of which has long since been lost. Against this strange and shadowy second Dark Age, the title character (in a quest reminiscent of an old Star Trekepisode!) seeks to relearn the lost art of making gun powder.

Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift (1726)

A slightly perverse addition to the list, but a neat one because it identifies part of what makes the subgenre so powerful. As is well known, Gulliver travels from place to fabulous place, encountering various outlandish, comic and troubling cultures. Invariably, of course, Swift’s satire is directed not so much at the foreign places as at Gulliver himself, who—in addition to being gullible—frequently derives the wrong lesson from what he experiences. The final visit, in which he is shipwrecked in the land of the horse-like Hounhynyms which are plagued by the clearly and barbarically human Yahoos, turns him into a tortured misanthrope incapable of spending time with people. The book is, like many dystopian novels, finally a searing critique of the way humanity’s stupidity and selfishness is allowed to dictate the terms under which everyone lives and, of course, dies.

A slightly perverse addition to the list, but a neat one because it identifies part of what makes the subgenre so powerful. As is well known, Gulliver travels from place to fabulous place, encountering various outlandish, comic and troubling cultures. Invariably, of course, Swift’s satire is directed not so much at the foreign places as at Gulliver himself, who—in addition to being gullible—frequently derives the wrong lesson from what he experiences. The final visit, in which he is shipwrecked in the land of the horse-like Hounhynyms which are plagued by the clearly and barbarically human Yahoos, turns him into a tortured misanthrope incapable of spending time with people. The book is, like many dystopian novels, finally a searing critique of the way humanity’s stupidity and selfishness is allowed to dictate the terms under which everyone lives and, of course, dies.

Part of what separates great dystopian novels from the rest is the sense that the messed up world presented is plausible, a credible extension of real world social problems. With the less convincing sort I find myself wondering how on earth a society could ever actually evolve in the way represented by the book. The world feels fictional because it’s clearly an artificial problem the author has invented in order for the plucky hero to fix it. When the dystopia does get fixed, the resulting world often looks uncannily like the one in which the reader actually lives. I’m more interested in dystopias that ring true because we can see them looming in some nightmare version of our own future. They stand not just as fictional environments in which our heroes can be brave, but cautionary tales about what might happen if we aren’t.

Top image: Earle Bergey cover art for The Day of the Triffids, Popular Library Edition (March, 1952)

A.J. Hartley is the bestselling author of a dozen novels including Sekret Machines: Chasing Shadows (co-authored with Tom DeLonge) and the YA fantasy adventure Steeplejack and its sequel Firebrand (available from Tor Teen). As Andrew James Hartley, he is also UNC Charlotte’s Robinson Distinguished Professor of Shakespeare, specializing in performance theory and practice, and is the author of various scholarly books and articles from the world’s best academic publishers including Palgrave and Cambridge University Press. He is an honorary fellow of the University of Central Lancashire, UK.

A.J. Hartley is the bestselling author of a dozen novels including Sekret Machines: Chasing Shadows (co-authored with Tom DeLonge) and the YA fantasy adventure Steeplejack and its sequel Firebrand (available from Tor Teen). As Andrew James Hartley, he is also UNC Charlotte’s Robinson Distinguished Professor of Shakespeare, specializing in performance theory and practice, and is the author of various scholarly books and articles from the world’s best academic publishers including Palgrave and Cambridge University Press. He is an honorary fellow of the University of Central Lancashire, UK.

Nitpicks re The Day of the Triffids: It isn’t just Britain; news reports the day before the green flashes are seen over England make it clear that it’s everywhere. Also there’s an editing cheese error in the description.

I would like to see a reboot of DT that actually presents the slow-motion disaster in the book. The only good one ever put on film was the miniseries from the early ’80s, and it’s hard to find. It should be set in the Cold-War-with-superscience that Wyndham imagined, with solving world hunger dangled before the masses as a distraction from international skullduggery–hence the ubiquitous triffids–while mysterious superweapons orbit silently overhead–hence the green flashes and, possibly, the plague. The triffids shouldn’t be murderous vegetable tigers. Their horror is that they are slow, but deadly, and everywhere. And no human enclave should be perfect, because Wyndham didn’t actually write a cozy catastrophe.

Folowing this train of thought: I loved how Station 11’s narrative of the breakdown of society hopped between narratives who were all linked through one person.

jenny islander: “The triffids shouldn’t be murderous vegetable tigers. Their horror is that they are slow, but deadly, and everywhere.“

So, the triffids were zombies, before zombies were cool? (Tongue in cheek; zombies have never been cool. Room temperature, maybe.)

This ties into my pet opinion that the ur-Zombie story has no zombies in it. I’m talking about “Leiningen Vs. The Ants”, the classic Carl Stephenson short story of man vs. ants.

From a piece I wrote in 2012: “The story, of a South American plantation owner facing an advancing horde of carnivorous army ants, pretty much has it all for the zombie fan: The army ants are essentially mindless, they’re seemingly without number, and they will eat you if you get in their way. Leiningen is the hero struggling to save his plantation (a stand-in for “civilization”) and his workers (“humanity”) from the Godless horde. Defenses are put in place, with some success. (“Peace through superior firepower” is, in part, through actual fire-power in this case.) But the defenses fall, one by one, until the hero finally has to directly confront the ants/zombies, at near-insurmountable risk to his own life, in order to save the remaining outpost of civilization and the humans still alive there.“

Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy features a very different but highly complex and all-too-plausible dystopia which takes environmental destruction, overpopulation, lawless cruelty, and the absolute power of capitalism to logical extremes. But the POV characters grew up in this setting (in diverse walks of life), so didn’t experience an abrupt society-level transition from non-dystopia to dystopia the way Offred did — and there probably wasn’t one. What they do experience is the very swift destruction of nearly all humanity, and the books are a blend of post-apocalyptic plot and pre-apocalyptic backstory.

I normally avoid dystopian fiction, but that trilogy snared me with fun science and environmentalist humor, then killed my optimism softly. A masterpiece.

@@.-@ Completely agree. I think Oryx and Crake is highly underrated in popular culture. Year of the Flood was even better, even if MaddAddam weakened the trilogy significantly.

I know you only have five books, but I really think “A Canticle for Leibowitz” should have been on that list. We see the society evolve (or devolve, depending on how you want to look at it) over the course of centuries.

@5: I agree. Year of the Flood was my favorite, largely because of the God’s Gardeners (all of their hyms are on YouTube, btw) and I think MaddAddam ran off the rails a bit by the end. Still, when Atwood advises readers to “stay hopeful,” I’m unsure whether she thinks we should hope that humanity will survive its own self-destructivenes — or that it won’t.