Someone—I honestly don’t remember who—gave me some writing advice early on in my career, and it stemmed from a George Orwell quote: “Good prose should be transparent, like a window pane.” The idea behind this statement, as far as this advice went, was that prose should simply be the vehicle by which you convey character and story—it should be as unassuming and inconspicuous as possible in order to focus on what really matters.

Well, like just about every piece of advice in writing, I’ve come to trust that “rule” about as far as I can throw it (which, considering it’s a metaphysical concept, is not far?). There’s certainly truth to it, but I’ve found that at least for me, reality is fraught with nuance.

The idea of prose as a windowpane just seems restrictive to me. I like to think of prose more in terms of a good camera lens. I’m no photography expert, but I know a little bit about the topic, and there are, well, a lot of ways to adjust the settings on a photograph, from aperture and exposure to shutter speed, color, depth of field, and many, many more. All of these tools can help make a photograph look better, enhance certain aspects, subdue others, make it brighter, darker, and so forth.

I think prose can do the same thing for a story.

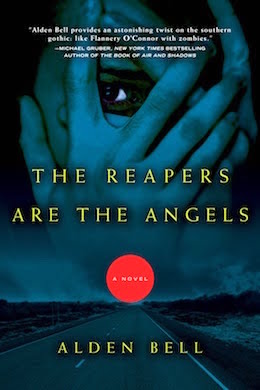

One of my favorite novels of all time is Alden Bell’s The Reapers are the Angels. The story follows a young girl named Temple as she navigates a post-apocalyptic zombie wasteland, and I’m not exaggerating when I say not only is it the best zombie novel I’ve ever read, it’s a serious contender for the best novel period. It’s … pretty fantastic. Like most good zombie tales, the “slugs,” or “meatskins,” as they’re referred to in Reapers, take a back seat to far more frightening, and often far more human, monsters.

One of my favorite novels of all time is Alden Bell’s The Reapers are the Angels. The story follows a young girl named Temple as she navigates a post-apocalyptic zombie wasteland, and I’m not exaggerating when I say not only is it the best zombie novel I’ve ever read, it’s a serious contender for the best novel period. It’s … pretty fantastic. Like most good zombie tales, the “slugs,” or “meatskins,” as they’re referred to in Reapers, take a back seat to far more frightening, and often far more human, monsters.

But what really impressed me about Bell’s novel, and what really made me love it, was the prose. Let’s just look at the opening few paragraphs:

God is a slick god. Temple knows. She knows because of all the crackerjack miracles still to be seen on this ruined globe.

Like those fish all disco-lit in the shallows. That was something, a marvel with no compare that she’s been witness to. It was deep night when she saw it, but the moon was so bright it cast hard shadows everywhere on the island. So bright it was almost brighter than daytime because she could see things clearer, as if the sun were criminal to the truth, as if her eyes were eyes of night. She left the lighthouse and went down to the beach to look at the moon pure and straight, and she stood in the shallows and let her feet sink into the sand as the patter-waves tickled her ankles. And that’s when she saw it, a school of tiny fish, all darting around like marbles in a chalk circle, and they were all lit up electric, mostly silver but some gold and pink too. They came and danced around her ankles, and she could feel their little electric fish bodies, and it was like she was standing under the moon and in the moon at the same time. And that was something she hadn’t seen before. A decade and a half, thereabouts, roaming the planet earth, and she’d never seen that before. […]

See, God is a slick god. He makes it so you don’t miss out on nothing you’re suppose to witness first hand. (3-4)

Those paragraphs hooked me, and didn’t let go. The prose is anything but transparent here—in fact, the character’s voice is so intertwined with the prose that it’s almost impossible to separate the two. I’d argue that the prose in Reapers is so powerful and so present that it effectively becomes a manifestation of Temple herself. The prose in Reapers is a living, breathing thing, with its own cadence, slang, its own ticks and its own tricks.

Temple acknowledges the power of words, and I don’t think it’s by accident that it comes early in the novel: “…she knows that words have the power to make things true if they’re said right” (11). Prose does have that power, and it helps me to acknowledge that power as a storyteller. Sometimes I want my prose with #nofilter; I want it to be as clean and transparent as possible so I can get to the heart of whatever is at the story. Other times, however, I need heightened prose, with elaborate imagery and a strong, distinctive character voice, because it will enhance whatever is at the heart of the story. It’s like, I dunno, freaking cybernetic implants for my story. It may look a little strange, it may take some getting used to, but I’ll be damned if the enhancements they offer don’t outweigh their wonkiness.

Reapers is awesome because it’s a story about faith, love, and beauty, and it tackles all of those subjects in the most dreary, horrifying setting possible. But despite the mangled, tattered world in which she lives, Temple’s hope and positivity are conveyed most powerfully through the prose style itself. It’s just…it’s just beautiful, ya’ll. If you haven’t read this book, you need to. If you have read it, go read it again.

Framing and lenses matter. How we tell a story matters. And with The Reapers are the Angels, Alden Bell not only tells a story that matters, he tells it in a way that matters, too. Temple notes part way through the novel, as she and a companion come across a museum, how important beauty is in the world, and how subjective it is to the eye of the beholder: “This is art … these things have gotta last a million years so people in the future know about us. So they can look and see what we knew about beauty” (118).

As readers, we get to see what Temple knows about beauty through the apotheosis of the novel’s prose, as it becomes Temple herself. We also get to see hints of what Alden Bell knows about beauty, too, in how he crafts that prose and Temple’s character. I sincerely hope that The Reapers are the Angels lasts a million years into the future, so people can see this specific form of beauty.

Christopher Husberg was born in Alaska and studied at Brigham Young University, where he went on to teach creative writing. His debut novel, Duskfall, was published in 2016, and was described as “Perfect for fans of Daniel Abraham and Brandon Sanderson” by Library Journal. His new novel, Dark Immolation, is available June 20th from Titan Books. He lives with his wife in Lehi, Utah.

Christopher Husberg was born in Alaska and studied at Brigham Young University, where he went on to teach creative writing. His debut novel, Duskfall, was published in 2016, and was described as “Perfect for fans of Daniel Abraham and Brandon Sanderson” by Library Journal. His new novel, Dark Immolation, is available June 20th from Titan Books. He lives with his wife in Lehi, Utah.

i was just kicking myself last night for loaning my copy to my brother. he hasn’t given it back and it’s too good not to have close at hand. the language is very much the secret to what makes the novel work. it paints a vivid image of a regressed landscape, exposes temple’s heart and language paints the more horrifying parts of the story with such immediacy. you picture the story clearly and you feel you are there.

I find the example offered to be incredibly transparent and poetic. I don’t find those two things opposed to each other. The opposite of transparent writing would be opaque writing that obfuscates the constructor’s verbiage and elaborately wise and studious musings. To make that last sentence transparent “The opposite of transparent writing is opaque writing, where word choice and style confuse the authors meaning instead of making it concrete.” I think transparent writing is the only option for good writing. That isn’t to say you cannot allow your voice to bleed through regardless of your voice, be it Hemingway or Faulkner. But word choice and arrangement in good writing are always transparent to the authors meaning.

Sometimes prose gets in the way. For instance, I couldn’t get through Janny Wurts’ The Curse of the Mistwraith, first in the series of Wars of Light and Shadow, because of the prose. I kept having to re-read sentences several times to understand what I just read. That’s not a good way to read a book.

Sofrina: I completely agree! And I’d be hard pressed to lend out my copy to anyone :-).

Grunge: I think that’s absolutely a valid way to read the passage. My experience was a bit different; when I first read the opening to the book, the voice was so strongly embedded into the prose itself that I had a difficult time seeing past it. But as I read, I appreciated the weight of the prose more and more until it became an inextricable part of the novel.

Austin: That’s exactly the point I’m getting at–sometimes, prose gets in the way, and that’s a bad thing. But when it enhances the reading experience, as it does with Reapers, it’s pretty incredible (even if, like me, you have to give the text the benefit of the doubt for a few pages).

I couldn’t agree more. Without her, the way she speaks, the intelligence………….but in a more common manner. I lent the book to a friend and she loved it, because of the common connection she felt with Temple.

I hate trying to read books from authors, such as Dean Koontz, that more or less, badger you with worthless words and speech in having to add far too much detail into the scene/setting/story. No room left for imagination or interpretation. You aren’t “allowed” to get to know their characters by just listening to them and trying to get to know them as you would a real person. They’re forced upon you. “This is who he is. He is MY character and you will only knows him as I want you too”………but Bell connected with Temple I believe. To write in that style, but still be able to bring out all of Temple. Her beliefs, fears, sadness, love, admiration. That had to come from somewhere besides the mind. Too many of these writers forget that most of the people that read their work are just average, everyday folk that long for a character that they can somewhat relate with. Temple is “us”. She just is who she is. She doesn’t sugar coat anything. She isn’t afraid to speak and let her thoughts and feelings come through is such a manner that 90% of the readers developed that caring, “wish you were in there helping that beloved character make it through”, emotion that a really good book is supposed to make you feel. The manner in which prose is used, but still somehow poetic, and able to touch a part of………well, nearly every review and/or post I’ve read about it.

I developed some heart troubles a few yrs ago, and had to retire. So I read A LOT. So much that I often forget most of each book, because I can’t find more than a few that can actually make you care for a character. I just move on to the next one and hope that it has that special connection that Alden Bell created with Temple. He took mud and sculpted an angel :D Wonderful book! One of my top 5 favorite that you will never be able to forget.