We all know traveling faster than light is impossible, yet it is perhaps the most common conceit we allow a science fiction story. Fans love to quibble over minor physics infractions despite having already given warp speed a pass. And it makes sense! Traveling at 186,000 miles a second is still pig slow when the galaxy—hell, even just our solar system—is your story’s playground. To hammer that point home, go now and have a look at this amazing video on YouTube. It’s a real-time journey through our solar system at light speed—the fastest possible speed one could ever hope to go—starting from the Sun and heading straight out from there. Come back in 45 minutes when you’ve finally passed Jupiter. Have a long think about how that uneventful, languid journey is the best we can ever hope for.

From a storytelling standpoint, it’s hard to maintain tension when a simple trip from Earth to Mars takes six months (about the best we can achieve, currently).

All of which is really to say: I get it. As a reader, a gamer, a lover of film and TV, I get it. I’m okay with FTL. Most of us are, I suspect. And as a storyteller, I get it, too. When you’ve got a cast of great characters that you want to send off to explore the galaxy, it’s nice if they’re still alive when they get there.

That’s all fine, but what I really love is fiction that takes FTL to the next level. Authors and creators who take this sort of necessary evil and make it interesting. Put some limits on it, layer on some stakes, or even just a dash of general weirdness. I love it when, even though it’s all technobabble, it’s good technobabble that gives me as a reader some feeling that there was thought put into the method.

Here’s a few examples.

Infinite Improbability Drive

Douglas Adams famously concocted this method when he’d written himself into a corner in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. His main characters were floating in the vacuum of space, and every solution he could come up with to rescue them seemed infinitely improbable. In classic Adams fashion, he turned this to his advantage, and so was born the Infinite Improbability Drive: A device that takes you to every possible position in every possible universe and eventually picks one to dump you at. Could be anywhere, and you could be anything when you emerge. Not only is an inventive idea, it fits perfectly with the fun and humorous nature of the Hitchhiker books.

Douglas Adams famously concocted this method when he’d written himself into a corner in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. His main characters were floating in the vacuum of space, and every solution he could come up with to rescue them seemed infinitely improbable. In classic Adams fashion, he turned this to his advantage, and so was born the Infinite Improbability Drive: A device that takes you to every possible position in every possible universe and eventually picks one to dump you at. Could be anywhere, and you could be anything when you emerge. Not only is an inventive idea, it fits perfectly with the fun and humorous nature of the Hitchhiker books.

Mass Relay

Made famous in the Mass Effect games and novels, this is actually an FTFTL solution. This universe allows for FTL drives, but even using one of those it would still take you years or centuries to travel long distances. To go faster than faster-than-light, you must use the ancient and mysterious Mass Relay network. What I love about these is the limit they impose: You can only go from one relay to another, creating something like a railway-network on the galaxy. Because of this, the relays become choke points, things to fight over and control, and that generates incredible drama.

Made famous in the Mass Effect games and novels, this is actually an FTFTL solution. This universe allows for FTL drives, but even using one of those it would still take you years or centuries to travel long distances. To go faster than faster-than-light, you must use the ancient and mysterious Mass Relay network. What I love about these is the limit they impose: You can only go from one relay to another, creating something like a railway-network on the galaxy. Because of this, the relays become choke points, things to fight over and control, and that generates incredible drama.

Skip Drive

Scalzi, too, gives us a solution-with-limits in Old Man’s War. While the Skip Drive can get you across space in the blink of an eye, the range is limited and, what’s more, you can’t be near a significant source of gravity to use it. This means ships can appear anywhere around a star provided they’re far enough out, and once arriving they still must travel in-system at conventional speeds. It also means a ship can’t just skip away at the first sign of trouble. Best of both worlds!

Scalzi, too, gives us a solution-with-limits in Old Man’s War. While the Skip Drive can get you across space in the blink of an eye, the range is limited and, what’s more, you can’t be near a significant source of gravity to use it. This means ships can appear anywhere around a star provided they’re far enough out, and once arriving they still must travel in-system at conventional speeds. It also means a ship can’t just skip away at the first sign of trouble. Best of both worlds!

Hyperspace-drive

The master of technobabble (and I mean that with the utmost respect), Iain M. Banks, deserves a mention here simply for how well he describes his hyperspace method. Details are spread out across the numerous (and wonderful) Culture novels, but I think the most tangible example is in Excession. Banks was second-to-none in his ability to describe something the reader knows is not possible or even based on actual science, and yet it rings true. Ships use exotic matter to dip into various levels of space-time energy fields, and push off against these hidden regions of space in order to gain momentum. The more exotic matter they have, the faster they can go. In Excession, in fact, a ship converts almost all its own mass into this exotic form of matter, in order to push its speed to staggering levels. I can scarcely do it justice here, you really owe it to yourself to go read the Culture books.

The master of technobabble (and I mean that with the utmost respect), Iain M. Banks, deserves a mention here simply for how well he describes his hyperspace method. Details are spread out across the numerous (and wonderful) Culture novels, but I think the most tangible example is in Excession. Banks was second-to-none in his ability to describe something the reader knows is not possible or even based on actual science, and yet it rings true. Ships use exotic matter to dip into various levels of space-time energy fields, and push off against these hidden regions of space in order to gain momentum. The more exotic matter they have, the faster they can go. In Excession, in fact, a ship converts almost all its own mass into this exotic form of matter, in order to push its speed to staggering levels. I can scarcely do it justice here, you really owe it to yourself to go read the Culture books.

(none)

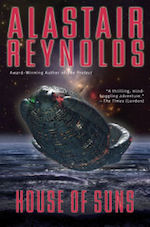

None? Yeah, none. Last but not least, I have to mention House of Suns by Alastair Reynolds, for the simple reason that there is no FTL here. Remember those reasons I mentioned earlier why authors and creators insert FTL? Well, to Reynolds’ endless credit, he embraces the FTL limit, weaving it into his worldbuilding and the story itself to amazing effect. Amazing because he doesn’t then constrain his story to our backyard. House of Suns still spans the entire galaxy. Yet it’s action packed, tense, and often frenetically paced. Better still, it never shies away from reminding us how much time is really passing. I love this book for many reasons, but as an author I love it because it takes a limitation we often immediately wave away and not only adheres to it but turns it to the story’s advantage. Masterful stuff from one of the best in the business.

None? Yeah, none. Last but not least, I have to mention House of Suns by Alastair Reynolds, for the simple reason that there is no FTL here. Remember those reasons I mentioned earlier why authors and creators insert FTL? Well, to Reynolds’ endless credit, he embraces the FTL limit, weaving it into his worldbuilding and the story itself to amazing effect. Amazing because he doesn’t then constrain his story to our backyard. House of Suns still spans the entire galaxy. Yet it’s action packed, tense, and often frenetically paced. Better still, it never shies away from reminding us how much time is really passing. I love this book for many reasons, but as an author I love it because it takes a limitation we often immediately wave away and not only adheres to it but turns it to the story’s advantage. Masterful stuff from one of the best in the business.

Top image from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005)

Jason M. Hough is the New York Times bestselling author of The Darwin Elevator, Mass Effect: Nexus Uprising, and Escape Velocity. He lives near Seattle, except when he’s lost in virtual reality.

OBJECTION!

All we know is that has not been achieved, yet!

OBJECTION!

That’s the opposite of some boneheaded anti-engineering claims

“heavier-than-air flight is not possible for humans”

“we will never break the speed of sound”

“we will never land on the moon”

BUT! those claims had no law of physics to back them up! It IS physically impossible, however, to outrace a beam of light! (Mostly based on text from Astrophysics for people in a hurry.)

I do like the jump point system (c.f the Mass Relay) the best, because it helps give a geometry to space and to the control of space.

One of Harry Harrison’s books (either Star-Smasher of the Galaxy Rangers or Bill the Galactic Hero?) had an FTL drive that worked by blowing up the ship like a balloon so that it touched its destination, then shrinking back down around the point that touched the destination.

The RPG Traveller 2300 had “stutterwarp” drive, which had the ship constantly quantum tunneling (IIRC) to a new location; the effect of which was that the ship was (sort of) in real space at all times, even when it was moving at FTL speeds.

Niven & Pournelle’s Alderson Drive in “Mote in God’s Eye.”

Has many of the same effects as Mass Relay.

@1 No, really, we know it’s not possible in this universe. Which is why practically every SF novel with FTL uses some sort of hyperspace that takes you out of this universe.

@5 — Even then, I don’t think there’s a way to have FTL travel (even if you’re leaving this universe for the actual travel) that doesn’t break causality and essentially give you access to a time machine, from certain frames of reference.

I also liked two examples from Joe Haldeman’s novels.

In The Forever War, you accelerate your ship to almost the speed of light (which brings with it all the relativistic problems, most notably time dilation) and smash it into a collapsar. You pop out light-years away, almost instantaneously, and then have to decelerate.

In Mindbridge, the Levant-Meyer Translation is a teleportation system that takes less energy the further you go. But you can only stay for so long, and then you teleport back. If you’re not in the right spot, you just vanish. (IIRC — it’s been years since I read this one.)

I like the FTL in Catherine Asaro’s Saga of the Skolian Empire. It seems to do a better job at exploring the relationship between speed, space, and time while still allowing for FTL travel. It’s more than just a hand-wave with a few basic rules that are common in most space operas.

Tanya Huff has the Susumi Drive in her Confederation/Peacekeeper books which has FTL travel takes up days of subjective time while nearly instantaneous in objective time. The idea could use some more exploration but the books aren’t focused in that direction.

Ansible?

Somebody who reads here might recognize this book. It starts generations after somebody created a new human subspecies. They have two thumbs, they give birth in a peculiar way that basically requires the baby to stay connected via the umbilical cord for days, they have very little body hair, etc. They were supposed to be the first of a new breed of human, but they were classified as Other and almost wiped out. They now live a rural life in a reservation on the U.S. Pacific coast. Meanwhile the humans have gone kind of Bladerunner.

The subspecies has this elaborate and very mathy team game played on a huge, complex board that everybody can come and watch, and you don’t realize until like the last chapter of the book that the teams are a secret group of engineers working out the math for FTL travel right in front of the human overseers. And then they reveal themselves to the rest of the subspecies and most of them get in their secretly constructed ship and leave. Anybody remember which one this is?

wow I have a lot to read!

Real world FTL or black holes or something already exist. That’s how Gibbs on NCIS can go from DC to NC in under an hour, and the WInchesters from SUPERNATURAL can go from Kansas to West Virginia almost as fast.

Scalzi offers up another variation in his latest, The Collapsing Empire: the Flow.

Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos does a pretty good job of blending FTL with non-FTL travel. In fact, the Mass Effect system sounds remarkably similar to his farcaster portals.

You forgot leprechauns. That remains my favourite source of FLY from “Giving it 14%.”

Well assuming a human could even survive going that fast people wouldn’t die traveling 100 light years at 99.99% the speed of light (actually reaching 100% is also thought to be impossible) because of time dilation. The closer to the speed of light you get the slower time goes for you. Still, taking 100 years from an outsider’s perspective to get somewhere isn’t particularly fun story wise.

Vonda McIntyre’s “Superluminal” which centers around the experience of piloting in hyperspace and the costs upon the pilots.

Sylvan Migdal’s completed webcomic Athena Wheatley. FTL’s a doddle once you learn how to rewrite physics. Dealing with the mega-environmental consequences is the hard part.

I think my favorites are mostly in the “organic drive” subtrope, ftl by means of living creatures

David D Levine’s short story The Tale of the Golden Eagle, recounting a legendary tale of good intentions and high consequences

Michael Baldwin’s webcomic Spacetrawler: chew carefully, there are very sharp bits among the whimsy.

@3: That was Bill, the Galactic Hero. Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers had the ftl drive that was powered by irradiated cheese.

Waters-of–Starlight by Stephen Marley is a rather beautiful and slightly disturbing short story in the Decalog 5:Wonders anthology. Hard to describe if you haven’t read it.

@5/auspex: FTL is only known to be impossible in this universe to the extent that we ‘know’ this universe to be correctly described by special and general relativity. Since that knowledge is primarily empirical, even after a century of ‘successes’ we are still just one well-designed experiment away from having to revise or abandon that ‘knowledge’. So, strictly speaking, @1/random22 is correct.

And that’s not even bringing in the aspects of (also empirically sound) quantum theory that challenge relativity.

I think these are reasons (aside from its obvious convenience for storytelling) why FTL has such staying power. It is such a perfect example of the core concept of speculative fiction, the notion of overturning one ‘fact’ of our world and seeing where it goes. And as the various examples in the post and comments show, there still remain multiple options for replacement ‘facts’ that contain the faintest whiff of plausibility, given the history of physics.

Roberta MacAvoy, in her sf book, The Third Eagle, used something like cosmic thread, which formed fixed FTL paths between worlds. A sort of hybrid one I remember is STL ships which can hook up FTL links between planets, but the FTL system requires terminals at both ends. I think it was titled Mission to Universe, but I read it about 3 decades back).

In the Orion’s Arm shared universe, the closest to FTL is wormholes, but the far terminus has to be moved at sub-light speeds to its destination. If the termini remain connected during transit, there is a wormhole permitting FTL between those two points.

Technically, neither special nor general relativity forbid FTL. Special relativity forbids objects from accelerating through light speed; it doesn’t forbid something from being created moving faster than light (although this does seem to be forbidden by the actual behavior of particles); GR permits things like Alcubierre bubbles to move FTL, but, again, but their construction requires exotic matter, which may not (probably doesn’t) exist. Causality may be confused by FTL, but saying it forbids FTL is probably wrong; there may restricted forms of FTL that don’t violate causality as we know it, and if an FTL system does seem to violate causality, we may just have to redefine it. Something may forbid FTL, but I don’t think it’s our preference for the order of events.

David Drake’s RCN series has a fun method of FTL that lets him play with 18th/c-style sailing ships in space.

The Battletech series has Jumpships, which carry with them a whole host of implications (they are super rare and valuable and targeting them is a war crime, they determine logistical limitations for interstellar campaigns, they have the chance of mis-jumps leading to outcomes ranging from interesting to horrific, and they offer the ability to use “pirate points” to jump far closer to a target world than the standard and relatively safe normal points allow).

Warhammer 40k has the Warp (shunt your ship into Hell and hope your demon-repelling force field keeps you safe enough to make it out again, and hope that you didn’t travel too far backward or forward in time).

@5 The list of things we knew was impossible is very long, but accessible on your tablet computer no matter where you are in the world. Everything is impossible until it isn’t.

Call me corny, but I like WH40k’s method, which literally requires one to go to hell.

The Jack McKinney Robotech novels had an interesting one; spacefold appears instantaneous to the travelers themselves, but (as they eventually discover) takes around five years of real time (between Earth and Tirolspace, at least. Jaunts around the ruins of the Masters’ Empire don’t seem to cause a problem, nor did the Earth-to-Pluto jump at the beginning of the First Robotech War).

Also, spacefold drives incorporating their own Protoculture generators (as opposed to power cells) have a disturbing tendency to disappear. As in, the ship emerges from fold with a big hole where their main drive used to be. In the last book, the SDF-3’s drives took the ship with them, and most of the book is about those (both on board and off) trying to figure out just where they ended up.

Spacecraft in many of Cordwainer Smith’s stories utilize a space-drive he called “Planoforming.” It’s first mentioned in “The Game of Rat and Dragon,” published in GALAXY in 1953:

“Planoforming was sort of funny. It felt like like— Like nothing much. Like the twinge of a mild electric shock. Like the ache of a sore tooth bitten on for the first time. Like a slightly painful flash of light against the eyes. Yet in that time, a forty-thousand-ton ship lifting free above Earth disappeared somehow or other into two dimensions and appeared half a light-year or fifty light-years off.”

The Aliens Colonial Marines handbook has time dilation reverse at faster than light speeds. So that a 1 ly trip that takes a day when viewed from the outside takes years aboard ship. That’s why they have ftl and cryosleep.

As a justification for a creepy monster movie trope, I found it quite impressive.

house of suns is one of my favorite standalone books

My favorite example of none is Charles Sheffield’s Between the strokes of night – if you can’t speed up the ship you slow down the people inside it.

“The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet” by Becky Chambers has a system where the first trip must be made in normal space, but from there a specialized ship can “punch through” hyperspace to connect the two points in space. After that, any ship can take the shortcut.

@3 @18 I think the FTL drive in Bill, the Galactic Hero is my favorite FTL drive of all time.

My favorite not mentioned so far is the one developed by the Big Brain in Asimov’s iRobot. Works just fine, but you spent some of the trip dead

Don’t leave out Fire Upon The Deep, where FTL travel is only possible as you move farther out from the galactic core.

@25 ah!!! I remember loving the idea/mystery/sheer-WTF of it, that you might initiate a jump, show up, and… your engine’s not there anymore. Which is what happened in the story that kicked it off, where not only did their engine disappear, they ended up beyond Pluto when they were trying to jump to the moon, AND it turns out they brought the city around the ship with them.

The Mass Effect “style” of FTL travel is semi-common within SF, isn’t it? There’s numerous examples, such as the WH40K Webway. And the … more dangerous, “Event Horizon” (the movie) style of FTL travel in WH40K of going through the Warp has the unique property in that you might arrive before you depart (though you’re much more likely to not arrive at all, or, arrive … different)

I’m kind of surprised to see Scalzi’s Skip Drive mentioned here at all, honestly. “It’s instant but you can’t do it near gravity wells” is a pretty standard FTL model. The interesting part of the Skip Drive is its operational method, which is that it works by moving the ship into a parallel universe where it’s already at its destination.

I have to mention House of Suns by Alastair Reynolds, for the simple reason that there is no FTL here.

Er, SPOILERS, but, yes there is.

“It’s instant but you can’t do it near gravity wells” is a pretty standard FTL model.

And for good reason!

I want to write a novel about interstellar travel!

– OK, well, it will take your characters thousands of years to go from star to star.

That’s no good. I want it to happen quickly.

– OK, just say there’s a magic box that allows you to zap from place to place instantly. Turn it on in New York, zap, you’re on a planet circling Tau Ceti.

But I still want to have exciting spaceships in my story!

– Ah. OK, well, how about this: there’s a magic box that allows you to zap from place to place instantly, but it’ll only work when you’re in deep space…

In fact I think I’m right in saying that House of Suns is the only Alastair Reynolds novel with faster-than-light travel! The “Revelation Space” series are resolutely Einsteinian. You can get close to c, if you’re an Ultra and you have a magic go faster box Conjoiner drive that produces unlimited reactionless thrust, but you can’t go beyond it.

Another approach is just to dismiss the whole problem. Bob Shaw does this in Orbitsville – there’s a brief explanation at the start of the book that, yeah, everyone thought that you couldn’t go faster than light, but then they tried it and it turned out you could.

“The Spice will flow” Frank Herbert “Dune”

Excellent list of books! (★^O^★)

@38, the only real answer to “how does sf author X’s FTL work?” is “handwavium.” No matter how “hard” it’s supposed to be as sf, FTL does not appear to be achievable within current understanding of the universe. It’s not forbidden by GR, but to achieve FTL or something functionally equivalent, requires matter that permits violation of the weak, dominant, and strong energy conditions, that is, exotic matter. This may be permitted by quantum mechanics, but it’s never been observed and may not exist in macroscopic quantities.

See Alcubierre, Miguel, “The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity”, 2000, https://arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0009013

I love the mass effect relays because of how insidious they become in hindsight. Their existence encourages life to settle around certain key points and discourages the research and development of other means of FTL travel. This makes civilizations much easier to cull for the Reapers. Fortunately, as we see in Andromeda, the most recent galactic civilization actually did develop a an alternative FTL engine. (It was mentioned earlier in the lore, but not actually widely used until the most recent game).

You left out my favorite. U.K. Leguin’s NAFAL drive.

My favourite Banks is still the Algebraist, where the Dwellers have a secret network of wormholes that allow instantaneous travel between their worlds, if you know the secret matrix transformation to find them in the first place.

My favourite Banks is still the Algebraist, where the Dwellers have a secret network of wormholes that allow instantaneous travel between their worlds, if you know the secret matrix transformation to find them in the first place.

I like 27: it always puzzled me that they were going into frozen sleep for these voyages but were still worried about missing their daughter’s birthdays, or could arrive at LV-426 within (presumably) a few weeks or months of the colony being wiped out. (Newt hasn’t been hiding out in those tunnels for years; she still looks the same age as in her photo, more or less.) Why didn’t they just… stay awake? Those are big spaceships, it’s not like you’d get cabin fever . The idea that time speeds up when you go FTL answers all those questions.

if you know the secret matrix transformation to find them in the first place.

Jon Snow knows what it is.

In reply to the query by Jenny Islander,

The book you are thinking of is “The Gameplayers of Zan” by M.A. Foster

Tor did an article on this some years ago, see:

http://www.tor.com/2009/05/08/alien-immersion-course-ma-fosters-the-gameplayers-of-zan/

More about the author here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M._A._Foster

I’m also a fan of the method in C.J. Cherryh’s Union/Alliance and (especially) Chanur novels — ships are equipped with “jump vanes” which push against … I don’t know, aether? Initially they’re used to raise the ship’s velocity to very near C; then they throw the ship into “jump”, which is some kind of not-quite-instantaneous-but-much-faster-than-light travel until they reach their destination and reverse the process. But the interesting thing is that it screws up your time perceptions when you’re in jump — it generally feels instantaneous, or pretty much instantaneous, but your bodily processes have been running so you emerge from jump exhausted and starving and probably slightly skungy (like if you haven’t showered for three or four days). But some people actually retain enough awareness to get up and move around the ship while it’s in jump …

@Stathis Avramis no. 48: There are sequels? There are sequels! Thank you!

@43, LeGuin’s NAFAL drive wasn’t faster-than-light: NAFAL stood for “nearly as fast as light.” The ansible was instantaneous, so communication was, NAFAL was slower than light, so travel wasn’t.

@49, and Ms Cherryh usually leaves all the gritty bits thoroughly unexplained: you see the effects, but not the mechanism Since any FTL is handwavium, that’s probably the best course for the authors.

@51 — Agreed. Explain the “rules” of FTL in your universe (how fast you actually travel, what the limitations are, etc.), but I don’t necessarily need three pages of imaginary infodump physics.

@52 If there you do spend three pages of infodumping physics it’d better be fundamental to the story. David Weber spends almost entire chapters on it but his FTL dictates pretty much everything about his space ships.

A few random thoughts:

A few commenters have pointed out that each book mentioned isn’t the first example of each type of FTL drive. I think that’s deliberate; it’s supposed to be the article author’s favourite examples of each.

I’ll also suggest that examples that side-step the light barrier (WH40K trips to the Warp, or Drake’s Leary series’ slightly less hellish take) don’t qualify, as they aren’t truly FTL… still enjoy them, though.

On the possibility of FTL IRL, I’ll refer you to Clark’s less we’ll know First and Second Laws…

It strays from the article remit (as it’s a film) but I loved the conceit that FTL had different settings (including the risky Ludicrous Speed) from Space Balls…

Finally, again it strays from the remit of the article (given its a to show that became books) but I always liked the warp drive from Star Trek I also liked the way TNG had an episode that revolved around how Warp Drive (particularly high warp) damaged space/time, so areas of high warp traffic in Federation space instituted a Warp speed limit of factor 2. The TV shows never seem to mention it again (though I think there were one or two books that followed it up). I kept hoping for a new post-Dominion War series set around a frontier ship, but the Warp Speed environmental damage adds new dimensions and responsibilities. The Borg’s Trans-Warp Conduit technology doesn’t have the same impact, so Apha Quardrant civilisation (Federation, Klingon, Romulan, etc) all have their star systems linked by the network. Exploration vessels traveling beyond this network, in addition to First Contact, also have the responsibility of extending the network. Also (once First Contact has been made) explaining the long term damage done by Warp Travel, how these Trans Warp Conduits are the answer, and (possibly with their permission) we’ll build one to your star system to demonstrate… you could guess how smoothly that would go. Instant drama

How is this author a New York Times best seller? He doesn’t even realize that warp drive has been proven to be possible. We just need to create an energy source that’s good enough to produce the amount of energy necessary. The EM drive is one possible solution but is still in the experimental phase. Matter / anti-matter is another possible solution.

@55, the amount of energy needed by the Alcubierre drive, which I suppose you are referring to, is so huge that matter/antimatter wouldn’t come near to providing it. And no-one knows if the EM drive can scale up to produce any reasonable amount of thrust.

@55, I think that the amount of energy required for a macroscopic Alcubierre bubble is about equal to the amount of energy in equivalent to the rest mass of Jupiter.

Even below the speed of light, the faster you go, the more your mass increases. So, even relativistic speeds without some sort of “jetless” drive are difficult to imagine. Unfortunately, I think that in the real world the answer to interstellar travel is, “Ya can’t get theah from heah.”

E.E.”Doc” Smith’s Lensman novels found a way to turn off the vessel’s inertia, which apparently avoids the speed limit – but with some interesting challenges ensuing when the ‘inertialess drive’ was turned off at the destination. As the series progressed, those challenges were explored more fully, and ultimately weaponized as inertialess planets…..

@57 I thought they’d gotten in down to a less unreasonable mass of exotic matter.

@58

Just about every interplanetary story has had huge amounts of handwavium for its interplanetary transport; there’s even more handwavium in STL interstellar flight.

Back on topic, I remember that there were a couple of 1950s era sf stories that treated the speed of light as barrier in the same way as was the speed of sound. Of course, the speed of sound was broken by a man-made object at least a century before the X-1.

A very personal form of FTL in L.E Modesitt Jr’s The Swan Pilot. Modesitt’s pilots guide their ships through a wild and dangerous hyperspace that their minds interpret through the images and stories familiar to them.

I really liked the the early history of FTL in LeGuin’s “a fisherman of the inland sea”. Several short stories in that book where she explores the concept but the title one is really cool.

Of course, the speed of sound was broken by a man-made object at least a century before the X-1.

Several millennia, actually. (That’s what the “crack” of a whip is…)

The trouble I see is that FTL immediately takes the science out of science fiction and into fantasy. Its not like the sound barrier where its an engineering problem, its the relationship between motion, distance and time. If you can ‘zap’ yourself somewhere, you’ve effectively invented time travel and can create acausal events – things that happen out of order in time to some observers. So either Einstein is wrong, and there is some preferred reference frame that properly orders events, or you really can’t go ‘faster’ than light because it doesn’t even make sense. All the Alcubierre stuff doesn’t get around this and is probably an unphysical solution to the field equations.

James Blish’s spindizzy from Cities in Flight.

forgot one of the most important

Dune: Folding Space

@65 – not necessarily. Einstein may have been wrong, and there’s evidence in quantum mechanics that he is. My favourite current theory (unless it’s been disproved and I don’t know about it yet) is that there is only one electron present in the universe, and it’s constantly cycling around all the electron’s positions almost (but not quite) simultaneously.

@67/erebaros: Dune’s space folding might require an asterisk, as it is never made clear in the six primary novels whether the characters themselves use the term literally or metaphorically. I think that Herbert’s creativity here lies mainly in the way he deftly handwaved towards both relativity (spacetime warping) and quantum theory (‘Holtzman effect’) in a way that gave the veneer of plausibility while avoiding details that could be easily contradicted by later real-world scientific advances.

—

@65/Chris: The possibility of different observers claiming different temporal orders for events (i.e. spacelike intervals) is a circular argument against FTL because its basic premise—that all causally-linked events are separated by timelike intervals—itself presumes that causality may only be mediated via mechanisms that propagate at or below the speed of light. Indeed, I expect that experimental verification of a spacelike interval between two events otherwise known to be causally linked will almost certainly be the first step towards any viable FTL drive, should it be achievable.

I wish that work on Alcubierre’s proposal had been better developed and more widely known back in my days as a TA, as it can be used to illustrate various aspects of cutting-edge science in a way that is accessible to undergrad-level science classes (regardless of whether it ends up being true). Objections to the concept on the basis of “mathematically valid, but unphysical” lead into discussions of the nineteenth-century recognition that the physical world is only a subset of all the things that can be described through mathematics (and experimentally verified phenomena only a subset of that subset!) and how acceptance of that fact freed people to explore intuitively non-physical ideas such as non-Euclidean geometries that eventually led to some of the breakthroughs in twentieth-century physics (e.g. general relativity). I’m also reminded of the trope in poorly-written fiction wherein a researcher announces “the experiment was a failure, we did not observe what we expected,” which fails to recognize that science is a process of hypothesizing and testing rather than simply confirming what we think we know; falsifying a seemingly ridiculous idea is often more valuable than confirming a plausible hunch, and obviously confirming a previously ‘ridiculous’ idea opens up all kinds of possibilities.

Arguably, a story that builds upon something farfetched-but-rigorous like an Alcubierre bubble is more in the true spirit of (so-called hard) science fiction than one that merely sticks to ‘established’ science, not because it is realistic but because it follows the spirit of science as a process of examination. Keep in mind that Alcubierre has acknowledged that he designed his metric with the purpose of exploring whether a Star Trek-style warp bubble could be made consistent with GR field equations, continuing the tradition of scientists and engineers who have been inspired to push the envelope to see whether stories that captured their imaginations could ever be brought closer to reality.

you are all water vapored,,, santa claus does it best

How about the anacapa drive from Kristine Kathryn Rusch (see Diving Novels)

A couple I like.

In John W. Campbell, Jr’s Arcot trilogy, there are actually two systems. The Earth scientists discover a system that allows them to warp space around their ship, and in this new space they set the speed if light as the lower limit of speed, and then travel through space FTL. From an enemy alien ship, the reverse engineer their method which uses a field that changes the rate at which time passes. By using a field that speeds up time, you can go FTL. By using a second field inside the first to reverse the effect, you don’t age instantaneously while doing so.

And a very new one – in the Ship’s Mage series, specially trained and powerful mages can move a spaceship from

outside a gravity well to another location no more than one light year away and no more than once every six or four hours without risking death. So you have a rotating team of mages, and having more mages mean you can go faster.