As with every other science, the first thing you must learn is to call everything by its proper name.

—Vicomte Sébastien de Valmont in Dangerous Liaisons

Move the thing! Um…that other thing!

—Vizzini, trying to give orders in The Princess Bride

That which we do not name, we cannot discuss. And like everything else, books have their own specialized vocabulary. Reading the comments on my first post here, I realized that some readers might benefit from a small visual dictionary of book-related terms. I’ll stick to features you’re likely to find on ordinary commercial book, but skip the ones that everyone generally knows (“paperback”, for instance).

I apologize in advance for the lack of Latin terms.

[Click here to be less like Vizzini and more like the Vicomte de Valmont.]

The six key terms for talking about a book are the six planes of its rectangular prism. They are derived from anatomical vocabulary.

|

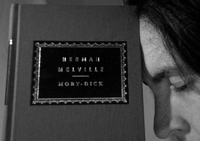

The front of the book is defined by the cover that the reader opens. |

|

The back is the side opposite the front. |

|

The head is the top of the book when it is held to be read. |

|

The tail is the bottom of the book when it is held to be read. Books are generally stored with their tails resting on the shelf. |

|

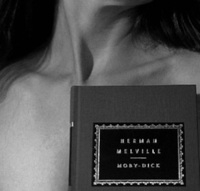

The spine is the vertical edge of the book where all of the pages are connected.

Western books generally have the spine on the left hand side of the front cover. Japanese and Arabic books both tend to have the spine on the right. |

|

The fore edge is the vertical edge of the book opposite the spine, where the pages are unconnected. |

Once you can negotiate the geography of a book, a few more terms may be useful for discussing its features.

|

The inner part of the book, consisting of all the pages, is known as the book block.

The sheets of paper that make up the pages of a book are called the leaves. The hard cover of most commercially bound books is known as the case. Hand bound books may not be cased in, but that’s another world from what we’re looking at here. The hard front and back covers of a book are called the boards. This dates back to when they were made of wood. |

|

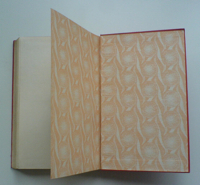

The pages at the beginning and end of a book are called the endpapers or the endsheets. They are frequently colored, patterned or marbled.

The endsheet that is attached to the board is referred to as the pastedown. The endsheet that is free of the boards is called the flyleaf. |

|

The edges of the cover that extend beyond the edges of the book block in a hardcover book are called the squares. |

|

The groove along the spine edge of the covers is called either the French groove or the American groove. (They are, for all intents and purposes, the same thing.) The groove is formed by the gap between the spine edge of the board and the spine, and forms the hinge that allows the book to open.

Some older styles of hand bound books don’t have them. Just so you know. |

|

There are two kinds of spines.

A book where the spine cover is attached to the spine of the book block is said to have a tight back or a flexible binding. Most paperbacks have tight backs. A book where the spine cover is not attached to the spine of the book block is said to have a hollow back. Most hard cover books have these. The colorful strip at the spine edge of the book block is called a headband. The upper one shown is sewn onto the book; the lower one is glued on. |

|

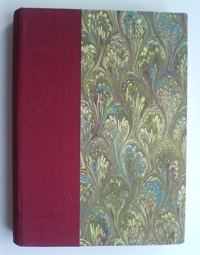

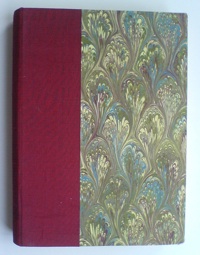

A book with leather or cloth on the spine and a weaker covering material (usually paper) everywhere else is said to have a quarter binding. |

|

A book with leather or cloth on the spine and corners and a weaker covering material elsewhere has a half binding.

(Books with the same material all over have full bindings, but that term is generally only used of leather.) |

Now you can amaze your friends with your astounding book-related knowledge! Go forth and describe books.

Great post, Abi! I wasn’t aware that it was customary to glue on the lower headband—I thought both upper and lower were somehow sewn on.

This sort of information can be very helpful if you are ever called upon to provide technical support to a book user.

@@@@@ pablodefendini

She means that the headband on the lower picture is glued and the one on the upper picture is sewn, rather than a single book having a sewn endband at the head and a glued one at the tail.

(I have never seen a modern commercial binding with a sewn headband; do they exist?)

OMG, live nude B00K pr0n!

Typically, I’ve only seen custom-rebound books with sewn headbands, although some books marketed as particularly ornate – such as, I believe, Alan Moore’s ‘Lost Girls’, and one of Yann Martell’s ‘The Life of Pi’ print runs- have been seen with their headbands sewn (at considerably higher price, I should add).

flickgc has it right; the upper image is an example of a sewn headband, such as is only done on fine bindings (and not all of those, because it’s a difficult skill to master). I included it to show what the modern version is derived from.

The lower book is a modern commercial binding with standard glued-in headbands. However, more and more hardcover books dispense with them completely these days.

Books will always have the same headband arrangement at both head and tail. If there’s one, there will be both, and they will be the same.

Interesting trivia one: some commercial Victorian binders would use striped shirt fabric wrapped around a core of string or cane for headbands. I have heard of, but never seen, a modern equivalent from India, where a commercial binder used halves of zipper track.

Interesting trivia two: I know a fine binder who had to submit his bindings to a contest anonymously. But he wanted to “sign” the work somehow. So he encoded his initials in the stripes of the hand-sewn headbands, in Morse code.

CliftonR

I love books.

Books are pretty cool.

abi @7: So do I. It is a struggle not to spend a lot more of my disposable income on them. (Despite my flippant comment, I like learning more about the terminology.)

P.S. Is there a technical bookbinder’s term for the box encasing a book or set of books, as sometimes seen in deluxe editions? Is that properly called a slipcase or does that mean something different?

CliftonR:

I know you were kidding. I was being flippant, or perhaps risque, back.

I’m glad the terminology is interesting. I was trying to make it memorable with the presentation, and I had fun picking out the opening quotes and figuring out how to show all six core terms.

Like the previous post, this is the sort of page that I’ve been wanting to find on the net for the last few years or so, and have given up and created myself.

Ooh, boxes, a whole ‘nother world of complexity. But most of them are for hand bound books, which is an area I’m mostly avoiding in these posts.

Yes, a slipcase is the usual box you’ll see for deluxe commercial editions. The book(s) stand on their tails inside it, and slide in and out. It covers everything but the spine.

You can sometimes (rarely) have a chemise, which covers the front, spine and back of a book that is in a slipcase. This is generally for books that are strong, but prone to soiling.

Beyond that, we’re into quite elaborate and expensive box-making, such as drop-spine boxes like I did for the 2005 Worldcon souvenir programmes. That’s far outside the mass market, though.

This is great – I love to learn this sort of stuff. Could you do another article on the different terms for the pages and material in books? Wikipedia has this series but the illustrative visual examples work far better for this.

Sure, Matt! (Don’t do it Abi! He’s just hoping you’ll pose for “spread.”)

Seriously, great post! I didn’t know the term “squares.”

This is a brilliant post. I learned more than I’d like to admit. Feel free to write sequels.

I loved the tail in particular, but I am frankly disappointed you didn’t go more visual with the fly-leaf.

Oh, neat! Thank you, abi. I will almost certainly never again bind a book (I bound a couple in high school as part of a class in typesetting and letterpress printing, but, much as I love books, haven’t felt the call to make them, and certainly don’t have the time, with all the other things I keep promising myself I’ll do), but I love learning about the details of others’ professions, especially the terminology. There’s a feeling of having a part of the world fit together precisely in front of you when you can name the parts of an artifact and know how it was created.

pbjoy: No worries; after all she managed to show “tail” without showing any tail.

pbjoy

You found me out. The entire post is intended to teach you the term “squares”. I have a rant about squares coming up.

No, really, I do.

Matt C Wilson

I don’t know most of the terms for the things inside the book. I kinda stop at book block and let the printers take over from there.

I’ll put it on the list, but it’s going to require research, which means it wouldn’t be soon.

So interesting mapping of a book as human’s body.

*does not need to expand an already expensive hobby*

*does not need to expand an already expensive hobby*

*does not need to expand an already expensive hobby*

Dammit Abi!

:D

Excellent post. I look forward to more.

great post; love the photos. i read your first one a couple of days ago and i’ve been waiting for the follow-up eagerly.

i’m a library science/archives master’s degree student and i was really disappointed when i came into the program to discover that the courses on bookbinding and repair and the like — which sounded fascinating to me! — had been discontinued the semester before i was accepted due to ‘lack of interest’. !!

i’m looking forward to your third post. :)

Another great post depicting a not as well known or widely talked about part of the world of books.

I am looking forward to the next installment!

Fascinating. Are there also names for the various dimensions of a book? The width of the squares, for example.

A question: what do you call it when books have leaves whose edges are a different colour? I’ve mostly seen them in red so far. It’s just the edges, never the whole page.

Tim May:

There are old specific names for the sizes of books, based on a general standard size of handmade paper in use. I can’t really add any information to the Wikipedia article.

Ironically, producing paper on machines reduced standardization in this area. Before, everyone made paper with roughly the same size of deckle and mold. Now it comes on rolls of enormous length and can be cut to the desired size. The upshot is that you can’t calculate book size based on the number of times you fold a sheet of paper any more.

Estara:

There is no general term for edge decoration apart from “edge decoration”. They can be dyed or stained (I have heard both terms), either on the head or on all three sides. This hides the inevitable color change of the page edges over time. Or they can be gilt with gold leaf, which does the same and protects the paper from dust. It also looks shiny, and many book fanciers are magpies at heart.

Account ledgers frequently had marbled edges, often matching the endpapers. This was to stop anyone from removing a page to alter the accounts, because the break in the pattern would stand out.

One intensely neat effect is fore edge painting, where you fan the fore edge out slightly, so there’s a millimeter or so visible of each page edge, and then paint a picture on it. You can do this twice per book (one in each direction), and the viewer only sees them by fanning the pages as well. There are some fantastic examples here.

Thanks, Abi. I’ve actually learned something and now reading Tor.com feels less like a sugary treat and more like a sensible snack.

My favorite bookbinding phrase is “full calf”, which I believe refers to a book covered entirely with leather. Is that right, or was the bookbinder who I heard use it referring to something else entirely?

RichR:

Yes, a full calf binding is a book that is covered entirely in leather, specifically calfskin.

Calfskin is a soft leather, easy to work with. It’s got a very fine grain, and takes gold decoration beautifully. Traditionally, it’s often golden-brown, but, like any leather, it can be dyed other colors as well. It was the traditional choice for the libraries of the wealthy during the 1700’s and 1800’s. Now it’s often looked on as the Wonder Bread of leather binding – easy, but a bit bland.

The usual alternative to calf is goat, which is often referred to as Niger or Morocco (slightly different styles of tanning, named after the places that British binders of the 1800’s got them from). Goat has a tougher fibre and a coarser grain, but gives a more natural appearance.

Bookbinders use other leathers as well, of course: I’ve seen books covered in things as varied as ostrich leather, horsehide and manta ray skin. I myself have used smaller pieces of fish (tilapia and salmon), eelskin (hagfish, actually) and chicken foot leather, but none of them are large enough to cover an entire book.

There is also a tradition of covering books in human leather (no, I am not kidding), but I’m saving that post for Halloween.

Wow – I can’t believe how much I’ve missed out on! (Chicken foot leather??? really?) I’ve dabbled in book making, but none of my resources – either instructional books or instructional people – have been as thorough and informative. This makes me feel much more well rounded.

“It also looks shiny, and many book fanciers are magpies at heart.”

This explains so much. My whole fetish re: book collecting is magpie induced!

The world makes sense now.

Hmmm, I’ve just realized that the phrase full calf appeals to my taste buds in a way that full goat just doesn’t.

So a book could conceivable be half chicken and quarter eel. I’m surprised Neal Stephenson doesn’t insist on something exotic for his books bindings.

Abi:

Ah, yes, I know (a little) about the paper sizes. I have a homemade chart I use to classify the sizes of my own books. But that wasn’t quite what I was asking about.

What I was wondering was whether there were technical names for particular distances in the, um, anatomy of a book. The distance from the head to the tail, for example; I’d call that the height, and this seems to be correct. The Wikipedia page on book sizes even clarifies that it’s talking about the “outside height”, i.e. of the cover rather than the book block. But of course there are all sorts of other dimensions that might have names, which it doesn’t mention.

Tim May:

Ah, I see.

I’ve never heard of an official set of terms for book dimensions. Height, width, thickness, outside height if you’re clarifying that it’s the cover height rather than the book block height.

This is not to say there isn’t such vocabulary out there, but I have never run across it,

Great post, Abi!

Okay, now to use the new vocabulary words:

I have several tight-back softcovers with glued on headboards. (Specifically, MAKE magazines) I’d like to re-bind them (in yearly bundles of 4 issues) so that they are more durable (hard cover) and will lay flat nicely on a table or workbench. Is there any practical way to do this, or would I be better off starting from scratch with freshly printed PDF’s so I can control paper size, arrangement, signature sizes, etc.?

Similarly, what methods are there to “rescue” older (but not rare/classic/valuable) used commercial hard-covers with glued headboards that are falling apart, and would also benefit from being able to lay flat nicely on a workbench?

Not that I’ll necessarily have time to get to this project in the forseeable future, but thinking about it is fun in and of itself.

Looking forward to the squares rant too. I like a good technical rant, even outside my field.

cajunfj40:

Sorry to be so long getting back to you. We were out of town.

I have several tight-back softcovers with glued on headboards.

I presume you mean glued spines? I don’t quite know what you mean by a headboard.

Is there any practical way to do this, or would I be better off starting from scratch with freshly printed PDF’s so I can control paper size, arrangement, signature sizes, etc.?

Sadly, starting off from scratch is the best option. If you want to try rebinding your MAKE magazines, this write-up is designed to help you. But he recommends YES, which yellows horribly over a very few years, and creates signatures that are very, very thick at the spine. I am not convinced the result would be satisfactory.

If you do print them off again, the trick is finding paper of the right proportions and grain direction*.

Then you have to do some sewing. There are a number of decent tutorials on the web for such things. This one is very good, apart from ignoring paper grain* and leaving a lot of stitching showing (though you could glue a cover over that). This one and its associated links are a reasonable introduction to Coptic binding, which is easy and lies nicely flat, but won’t take much carrying around. And for more traditional stuff, I wrote this overview a few years ago.

If taking up bookbinding is too much, you can also get a 3-ring binder. Seriously: don’t forget the simple solutions in the quest for Teh Shiny New Hobby.

—–

* paper grain: I feel another article coming on. But in short, it’s the way the fibers lie in the paper. It affects how well sheets fold and tear, and when, where, and how much they swell when wet. If you use adhesives on your spines, you really want the fibers running head to tail, which is not what you get when you fold a standard sheet of office paper in half.

evilrooster:

No worries. I took forever to check back here, too! I meant headband, but spine was my first guess and I probably should have run with it.

Thanks for the suggestions and the links! I’d thought of three-ring-binder before, but I’ve had issues with pages tearing out and “overly filled” binders exacerbating that problem. Maybe a more “specialty” multi-ring binder would work. I hadn’t recalled the MAKE No. 5 article on re-binding the magazines having added paper to make the signatures, but the extended version in the link you provided is much clearer, and could be used to similar effect to get pages for a binder with more meat around the holes. Hmm, that and most binders I’ve seen have the rings and mechanical action bits riveted on, so they could be yanked out and re-attached to some other cover material, like diamond-plate aluminum…

Could a loose-back cover be used with the Coptic binding and preserve the “lay flat” characteristic? Something that would allow more carry-around (or, more accurately, “fall off the bench”) toughness?

Thanks again for your comments!

Hi.

Can you help, Inc looking for the name to describe a landscape book with the spine on the top not the side. Please let me know when you can.

Thanks

God bless

Is there a name for the metal spiral hinge on some books and calendars?

What is the name of the cloth strip which is used to mark the page which you stopped reading.

Hi,

Wonderful resource. Thanks for the effort. Just a heads up though. I’ve tried 2 browsers and with both the pictures are far too small. You can tell as the page loads they’re supposed to render larger, but they get tiny pretty quick.

I was looking at the code and noticed the viewport settings. I imagine they render well on iPhones or iPads. They just aren’t working on Chrome or Opera desktops.

Anyway, I got my question answered without the pic, so that’s good!

Thanks again,

Rick

Great post. Included everything I need to know. My only beef is that on my iPad the pictures are about a quarter of an inch. Is it just me or could they be bigger?

What is a fore edge called when it is not trimmed flush, but has variations in the page width?