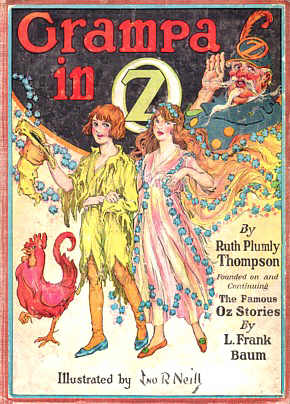

Again and again, the Oz books had stressed the abundance and wealth of Oz. In only one previous book (The Patchwork Girl of Oz) had any Ozite faced something even close to economic ruin. The last two books had shown lost wanderers easily able to feed themselves off trees and pre-cooked (and presumably dead) birds conveniently flying through the sky. Grampa in Oz rocks this comforting image by introducing something new to Oz: poverty.

The tiny Oz kingdom of Ragbad, veteran of several past wars, is in severe economic decline, in part because the king has spent his fortune on tobacco and bills. Instead of growing fine clothing, their trees now grow rags, tediously and painfully sewn into sad little rag rugs. Most of the workers and servants have fled for better jobs. The kingdom’s only money—money? In Oz?—comes from the rag rugs, and even the queen has shed her title and turned to work. Only three loyal servants remain: Pudge, a seer with the gift of prophesying events after they’ve occurred; a footman; and Grampa, a veteran of several battles, which have left him with a genuine game leg—it opens up into a board game. (Ok. It’s a terrible pun. But as a board game fanatic I am enthralled.)

The description, right down to the failing crops, impoverished but still proud aristocrats, the economic stress, and the last few loyal servants refusing to desert the family echoes, perhaps unconsciously, the nostalgic popular literature of the post-Civil War American South, with the carefully crafted legends of a once proud aristocracy clinging to its traditions even in the face of economic ruin. (I think it significant that Ragbad previously produced clothes, and particularly cotton clothes.) Thompson even includes the proud old soldier with his war stories and injuries, smoking good quality tobacco. Not coincidentally, the book features the return of money to Oz.

(Interestingly enough, this 1924 book—the first Oz book with such a focus on tobacco—contains a subtle anti-smoking message. Buying tobacco is one of the main things that got the country into this mess, and smoking tobacco continues to get the characters into further messes, even as they use snuff to take down a dragon.)

When the final blow literally rains down, taking the head of the king with it, the few remaining inhabitants realize that something must be done—after taking the time to replace the king’s head with a nice doughnut. (It appears to be an improvement, plus, tasty!) The doughnut head safely secured, Prince Tatters and Grampa head out to find the king’s real, non-doughnut head and the prince’s fortune, or, as Pudge suggests, a princess with a fortune. The romantic Grampa wants the prince to marry for love, but, Pudge notes, they must be practical.

So far, I admit, this does not sound much like an Oz book. The conversation about marrying for money feels particularly new—marriage was rarely a concern in previous Oz books, and money, never. And yet, this is Thompson’s most thoughtful take on Oz yet, a consideration of what it might actually mean to live forever in a fairy country. How much can you be expected to focus on the important things—and what is important?

Too, the book contains some of her loveliest images. As Grampa and Tatters travel, they encounter a marvelous garden with a young maiden literally made of flowers (she continally sheds petals, making her footsteps easy to follow), a cheerful weathervane named Bill blown in from Chicago (apparently, Chicago winds are even stronger than I thought), an island of fire, a fairy who shepherds stars, and an iceberg, where after a few drops of a magic potion, Tatters dances with the flower maiden, leaving petals scattered all over the ice. The king’s head is right where you might expect a king’s head to be. It feels right, not just for a king, but for this book. And if the plot bears more than a small resemblance to Kabumpo in Oz, it’s handled here with more richness and depth.

And while we can certainly fault Ozma for once again failing to notice that one of the kingdoms she is supposedly responsible for has fallen into disarry, the result is characters far more practical and knowledgeable than their counterparts in Kabumpo. Under the circumstances, they are also surprisingly willing to enforce Ozma’s anti-magic law. I should be astounded that the Ozma fail continues even in a book where the Ruler of Oz barely makes an appearance, but, well, I’m not.

With all this, the book is funny. Not just for the puns, but for the grumblings of Grampa and the wonderings of the frequently bewildered Bill, who has agreed to go by the name of Bill but remains uncertain what name he should come by, and who seeks for a fortune, and the meaning of fortune, with laudable determination. A sideplot follows the adventures of Dorothy and Percy Vere, who endeared himself to me by his habit of launching into terrible poetry whenever stress, persevering with poetry (I know, I know) against all reason. (He usually forgets the last words of the poem, allowing readers to try to guess the rhyme before Dorothy or someone else does. It adds to the fun of reading this book aloud.)

And yet, over all of this magic and humor, Thompson adds subtle, discordant touches in her expected happy ending. The king’s head does not want to return to the reality of his failed kingdom and Oz. Urtha cannot remain a flower fairy, and Ragbad never does save itself through its own resources. Instead, the kingdom relies on a yellow hen that lays golden bricks, which is all very nice, except, not only is this not an original idea in a book otherwise brimming with original ideas, the hen doesn’t belong to Ragbad. It belongs to the king of Perhaps City, and at some point, may return there, leaving Ragbad destitute again. And I question how useful that gold could be in the rest of Oz, which seemingly gave up on money years and years ago. Thompson would touch on this point in later books, but Oz is still not a country where currency is of great use. And although Grampa in Oz ends with a party, it’s one of the few parties that takes place outside the Emerald City, without Ozma and the other celebrities of the Emerald City, emphasizing Ragbad’s isolation. It’s harder than it sounds to live in a fairyland, Thompson suggests, even with the concessions (the ability to choose to age or not age) she gives her characters. It was a theme she would revisit later.

Mari Ness is rather relieved that she does not trail flower petals wherever she goes—think of the cleaning involved. She lives in central Florida.

The way that series expectations constrain and inspire writers is fascinating, and this sounds like an excellent example.

Nice writeup. This was the first of the Thompson Oz books I read, and I honestly never noticed the change to having money again, or poverty existing in Oz (hey, I was a kid). It seems like at this point Thompson had kind of hit her stride with Oz, both fitting her style more closely to the older books, and being unafraid to make changes where she wanted to.

Tip didn’t really live in high style back in The Marvellous Land of Oz, did he? Or is it all rather relative?

@katenepveu – I actually think Thompson got considerably better after she gained the confidence to break away from Oz expectations and focus on her own characters, which would take a few more books. Even here, the inclusion of Dorothy shows her sense that she still had to include well known Oz characters in major roles, and the next few books continue to follow that pattern. Here those expectations are still constraining her imagination, if not her love of puns.

@wsean – Even after this, the Ozites don’t use a lot of money – Betsy Bobbin, as we’ll see, ends up using an emerald ring for barter since she’s forgotten to bring along any coinage, showing that she’s unused to bringing money along. But Thompson is acutely aware that many of her heroic characters do have an interest in wealth – Peter as the example that first pops to mind, but he’s not the only one.

I do think this is the best of Thompson’s early books, but I think she more hit her stride after The Yellow Knight. (I, um, might be a bit biased by the rocket in Yellow Knight).

@NomadUK My impression in The Marvelous Land of Oz was that Mombi was keeping Tip hard at work less from economic necessity and more to keep him too busy to ask questions. Certainly they were staying in an obscure location and maintaining a rural lifestyle, but that’s not quite the same as the loss of wealth, servants and social status portrayed here. The rest of Oz in The Marvelous Land of Oz is clearly very wealthy, wealthy enough that no one hesitates to stuff the Scarecrow with money or says “hey, we might need this cash later.”

do you take comments 9 years later? lol. My memory is that wherever Urtha walked, flowers sprang up under her feet. Not that she shed flowers..

Even though every time you mentioned the flowers, my inner head did a little jerk, I love this article. I love your take on one of my favorite Oz books. I think Grandpa and Bill are two of Thompson’s most fun characters. I look forward to reading more of these.