If ten people are talking about urban fantasy, they’ll actually be talking about six different things. When I first started paying attention to things like sub-genre definitions (early 1990’s), the term urban fantasy usually labeled stories in a contemporary setting with traditionally fantastical elements—the modern folktale works of Charles de Lint, Emma Bull’s punk elf stories, the Bordertown series, and so on.

But the term is older than that, and I’ve also heard it used to describe traditional other-world fantasy set in a city, such as Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar stories. Vampire fiction (the books of Anne Rice, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, and P.N. Elrod for example) was its own separate thing.

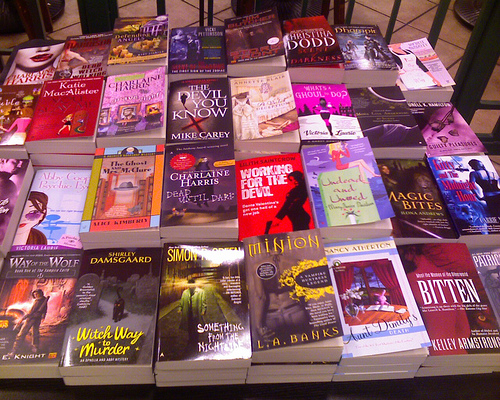

Lately I’ve been wondering—when did “urban fantasy” come to be used almost exclusively to describe anything remotely following in the footsteps of Buffy and Anita? Stories with a main character who kicks ass, and with supernatural beings, usually but not exclusively vampires and werewolves (with liberal sprinklings of zombies, angels, djinn, ghosts, merfolk, and so on) who are sometimes bad guys but often good guys. Those ubiquitous covers of leather-clad women with lots of tattoos.

I’m using my own career to set up guideposts here, since the books in the Kitty series have nicely mirrored the rise in popularity of the current urban fantasy wave. For example, when the first book came out in 2005, no one was calling this kind of thing urban fantasy. That all changed within a couple of years. Another disclaimer: This is all my observation, and if anyone has other data points or observations to share, which will expand or debunk my little hypothesis, I’d love to hear them.

December 2002: I started writing Kitty and The Midnight Hour. (The first short story featuring the character appeared in Weird Tales in 2001. You can read that story, “Doctor Kitty Solves All Your Love Problems,” on my website.)

November 2003: I started shopping around the novel in earnest, calling it “supernatural/dark fantasy.” It didn’t occur to me to call it urban fantasy, because that was something different, or so I thought. One agent told me that while he liked the book, he was going to pass on it because he didn’t know how he would sell it. (This is important. In December 2003, the whole vampire/werewolves/mystery/kick-ass heroine thing wasn’t enough of a trend for at least this literary agent to notice it.)

July 2004: Kitty and The Midnight Hour sold to then Warner Books.

August 2004: I had an embarrassing conversation with my new editor in which she compared my book to those of Kim Harrison and Kelley Armstrong. I had not heard of them.

A couple of weeks later, I went to the dealer’s room at Worldcon in Boston with the mission of checking out these titles and others, and I found a ton—L.A. Banks, Charlaine Harris as well as Harrison and Armstrong. I thought, “Holy crap, the market is oversaturated, my book will sink like a stone out of sight.” I was wrong.

November 2005: Kitty and The Midnight Hour was released. Reviews often referred to the growing popularity of the genre, but didn’t use the term “urban fantasy.” (This 2005 review called the book “supernatural fantasy.” Another common label was “the werewolf/vampire genre.”)

2005-2006: RT Book Reviews categorized the first two Kitty books as “Paranormal, Mystery/Suspense/Thriller.” (The link goes to a list of all my books on the site, showing the evolution of the genre label.)

2007: The third book, Kitty Takes a Holiday, was listed in RT Book Reviews as “Werewolf, Paranormal/Urban Fantasy.” All the subsequent books were listed as “Urban Fantasy, Paranormal/Urban Fantasy.” I sat on Urban Fantasy panels at DragonCon and ComicCon. RT Book Reviews Reviewer Choice Awards included a category for “best urban fantasy protagonist.” (Kitty Takes a Holiday, was nominated; Kim Harrison’s For a Few Demons More won.)

2007-2008: It’s around this point that urban fantasy as a sub genre became totally ubiquitous and people started noticing just how many covers with tramp stamps there were. People started asking me, “So, when do you think the bubble is going to burst?” As I mentioned above, I thought it was going to burst in 2005. As it turned out, instead of the market being saturated then, I got on the bandwagon exactly at the moment as it turned into a nuclear-powered locomotive.

It’s also around this time I started asking on convention participant questionnaires if I could please be put on other panels besides “What’s up with all this urban fantasy/kick-ass heroine stuff?”

May 2009: The Urban Fantasy issue of Locus. Rather than any bubble bursting, the True Blood TV series based on Charlaine Harris’s novels and the Stephenie Meyers Twilight phenomenon seem be to supercharging an already supercharged genre. (I do wish werewolves would get a little more attention amidst this vampire love-fest.)

2010 and beyond: All my predictions have been wrong so far, so I’m not going to make any.

And there you have it. Before 2007, the term urban fantasy had not yet morphed into its current usage. By 2007, the term was everywhere. Why? That, I don’t know, though in a recent conversation a fellow writer suggested that this particular usage came from the romance community as a way to distinguish hard-edged stories from paranormal romance which feature a specific couple’s relationship and ends with “happily ever after.” I think there may be something to this.

I’d speculate that the term didn’t come from any one person or publication. These books definitely have their roots in the same tradition as what I call “old-school” urban fantasy that came before. It’s all asking the same questions about what would magic and the supernatural look like butted up against the modern world? The term has become useful as a label for this particular kind of book, which is why, I think, it’s become so ubiquitous in such a short amount of time.

Story pic via Jeff VanderMeer’s blog.

Carrie Vaughn is the bestselling author of a series of novels about a werewolf named Kitty, as well as numerous short stories in various anthologies and magazines. She’s also a contributor to the Wild Cards series edited by George R. R. Martin.

There have always been supernatural stories around, just this particular subgenre owes a lot to Joss Whedon/Buffy. It takes a lot less books to make a genre successful than it takes for an audience for a tv show.

My only other comment is its hard to weed out the trash from the decently written books right now. I did enjoy yours, but 3 of the last 4 books I picked up were badly written garbage.

While I’m not a fan of the subgenre (I think the closest I’ll get is Tim Powers, James Blaylock and Neil Gaiman), I do like the discussion of what the genre details.

If nothing else, it reminds me of this exchange from The Office:

Michael: Now this gentleman right here is the key to our urban vibe.

Stanley: Urban? I grew up in a small town. What about me seems urban to you?

Nice historical analysis. Thank you!

I don’t recognize all the books in the picture, but WAY OF THE WOLF (down in the lower left corner) is SF–alien invasion of the Earth, scattered resistance fighters, that sort of thing.

Thanks for the timeline.

To me, in the past few years, “urban fantasy” has become almost as big a genre-umbrella as simply “fantasy” or “scifi.” It covers so many different sorts of books that happen to have a similar setting–like in the picture above: Mike Carey bears very little resemblance to Katie McAllister, and McAllister’s books are sort of a more romantic cousin to Kelley Armstrong’s, etc. And then you have the Charles de Lint and Emma Bull sort of stuff, or some Elizabeth Bear.

It’s interesting to me how much variety there is between different splinter-groups of genres within urban fantasy.

Datapoint: in May 2007, RT Book Reviews ran a big article on urban fantasy and consolidated the urban fantasy review from the paranormal and science fiction/fantasy section into a subsection of paranormal. Sometime last year, they moved urban fantasy into its own section, although on the website it still shows up as belonging to paranormal.

I do know that RT’s differentiation between paranormal romance and urban fantasy has a lot to do with whether or not there’s a HEA at the end of the book–although it’s usually pretty obvious if a book is urban fantasy or a paranormal romance. So I think your fellow writer’s idea that the term for this type of book came from the romance community is, at least, partially correct.

Like another commenter said it seems like for every 3 books/series I pick up that I enjoy I pick up at least 2 that I have no idea why they’re published. I always figured anything that is set in a contemporary setting, recognizable as ‘our world’ but with supernatural elements and the romance is only a piece of the puzzle–its urban fantasy. Anything that has the above, but the romance is the most important detail–paranormal romance.

I’ve gotten into long debates with people at stores over whether the Southern Vampire series (which began its life in the mystery section of the bookstore and stayed there until like book 4 or 5) can be considered UF or PR.

I understand what you mean though, I remember calling UF’s ‘supernatural fantasy’ back in the day when I went looking for books like Buffy (or Charmed).

I’ve always understood the difference between the current definitions of “urban fantasy” and “paranormal romance” to be that paranormal romance focuses on the relationships and usually ends with the HEA. Paranormal romance series tend to feature a different couple in each book rather than focus on a single main character through all the books.

And yeah, urban fantasy is a huge umbrella, which I think is part of why it’s been so popular — it appeals to so many different tastes. It’s also been around for a really long time, which does rankle when some people talk about the “hot new genre.” I just found a copy of Jack Williamson’s Darker Than You Think, for example, which wouldn’t be at all out of place in the current UF wave.

elitan, I’m probably the reason RT–wisely, I think, because of the differing urban fantasy and paranormal romance expectations you mention–moved urban fantasy into a separate category under paranormal.

In the fall of 2008, my Delilah Street urban fantasy, Brimstone Kiss, was mistakenly reviewed as paranormal romance. It was not a rewarding experience for the reviewer or myself. RT very professionally published a prominent correction on the mistake, and now that can never happen again. :))

And Steve Stirling’s “A Taint in the Blood” is a sequel/homage to “Darker Than You Think.” He has sold it as urban fantasy and it is quite good if you don’t mind kink. His villains – especially his primary villain Adrienne – do go in for it. Luckily, so does the heroine, so she knows how to survive the villains.

There are a (very)few Urban Fantasies that don’t have “Chicks in Tight Pants” on the cover the Dresden Files being the most prominent.

The link to your short story is broken: it should start http:// rather than https://

As of late I’ve actually been hearing ‘Urban Fantasy’ replaced with ‘Contemporary Fantasy’ because of the very thing you mentioned; a lot of it really is not urban. Seems like it might be a slightly better umbrella genre title than Urban Fantasy.

Eek, thanks momerath. As I do not have editing powers I’ll try to forward it to the powers that be…

Also, see Jeff VanderMeer’s take on the subject:

http://www.jeffvandermeer.com/2010/07/09/urban-fantasy-from-whence-came-you-and-where-are-you-going-with-that-trope/

@carrie, @momerath–Link fixed! Thanks for the heads up!

You might be interested in this: http://juno-books.com/blog/?p=410.

Nice post.

Reminded me that we used to call Tanya Huff’s Blood series or the Sonja Blue novels “Dark Fantasy”, which as Genre seems now to have been all but absorbed by “Urban Fantasy” … It’s like trying to work out when “Goth” became “Emo”, or, to stay more on topic, where exactly “Steampunk” began.